Washington Navy Yard

|

Washington Navy Yard | |

Aerial view of Washington Navy Yard, 1985 | |

| |

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°52′24″N 76°59′49″W / 38.87333°N 76.99694°WCoordinates: 38°52′24″N 76°59′49″W / 38.87333°N 76.99694°W |

| Built | 1799 |

| Architect | Benjamin Latrobe et al. |

| Architectural style |

Colonial Revival Late Victorian |

| NRHP Reference # | 73002124[1] |

| Added to NRHP | June 19, 1973 |

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy.

The Yard currently serves as a ceremonial and administrative center for the U.S. Navy, home to the Chief of Naval Operations, and is headquarters for the Naval Sea Systems Command, Naval Reactors, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Naval History and Heritage Command, the National Museum of the United States Navy, the U.S. Navy Judge Advocate General's Corps, Marine Corps Institute, the United States Navy Band, and other more classified facilities.

In 1998, the yard was listed as a Superfund site due to environmental contamination.[2]

History

The history of the yard can be divided into its military history and cultural and scientific history.

Military

The land was purchased under an Act of Congress on July 23, 1799. The Washington Navy Yard was established on October 2, 1799, the date the property was transferred to the Navy. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy. The Yard was built under the direction of Benjamin Stoddert, the first Secretary of the Navy, under the supervision of the Yard's first commandant, Commodore Thomas Tingey, who served in that capacity for 29 years.

The original boundaries that were established in 1800, along 9th and M Street SE, are still marked by a white brick wall that surrounds the Yard on the north and east sides. The next year, two additional lots were purchased. The north wall of the Yard was built in 1809 along with a guardhouse, now known as the Latrobe Gate. After the Burning of Washington in 1814, Tingey recommended that the height of the eastern wall be increased to ten feet (3 m) because of the fire and subsequent looting.

The southern boundary of the Yard was formed by the Anacostia River (then called the "Eastern Branch" of the Potomac River). The west side was undeveloped marsh. The land located along the Anacostia was added to by landfill over the years as it became necessary to increase the size of the Yard.

From its first years, the Washington Navy Yard became the navy's largest shipbuilding and shipfitting facility, with 22 vessels constructed there, ranging from small 70-foot (21 m) gunboats to the 246-foot (75 m) steam frigate USS Minnesota. The USS Constitution came to the Yard in 1812 to refit and prepare for combat action.

During the War of 1812, the Navy Yard was important not only as a support facility, but also as a vital strategic link in the defense of the capital city. Sailors of Navy Yard were part of the hastily assembled American army, which, at Bladensburg, Maryland, opposed the British forces marching on Washington. The Navy Yard sailors, and Marines of nearby Marine Barracks, Washington, D.C., were in the third and last line of defense at Bladensburg. Together, they fought hand to hand with cutlasses and pikes against the British regulars before being overwhelmed. As the British marched into Washington, holding the Yard became impossible. Tingey, seeing the smoke from the burning Capitol, ordered the Yard burned to prevent its capture by the enemy. Both structures are now individually listed on the National Register of Historic Places. On 30 August 1814 Mary Stockton Hunter, an eyewitness to the vast conflagration wrote her sister: “ No pen can describe the appalling sound that our ears and the sight our eyes saw. We could see everything from the upper part of our house as plainly as if we had been in the Yard. All the vessels of war on fire-the immense quantity of dry timber, together with the houses and stores in flames produced an almost meridian brightness. You never saw a drawing room so brilliantly lighted as the whole city was that night.” [3]

Civilian Employment

From its beginning the navy yard had one of the biggest payrolls in town, with the number of civilian mechanics and laborers and contracters expanding with the seasons and the naval Congressional appropriation. Following the War of 1812, the Washington Navy Yard never regained its prominence as a shipbuilding facility. The waters of the Anacostia River were too shallow to accommodate larger vessels, and the Yard was deemed too inaccessible to the open sea. Thus came a shift to what was to be the character of the Yard for more than a century: ordnance and technology. The Navy Yard grew during the next decade to become by 1819 the largest employer in Washington D.C., with the total number of approximately 345 workers. In 1819 Betsey Howard became the first the first female worker documented at the navy yard (and perhaps in the federal service), she was followed shortly after by Ann Spieden. Both Howard and Spieden were employed as horse cart drivers, "and like their male counterparts employed per diem, at $ 1.54 a day, working whole or part days as required." [4] [5]

During World War II the Washington Navy Yard at its peak employed over 20,000 civilian workers including 1,400 female ordnance workers.[6]

The Yard was also a leader in technology as it possessed one of the earliest steam engines in the United States. The steam engine was the high tech marvel of the early District and often commented on by authors and visitors. Samuel Batley Ellis an English immigrant, was the first steam engine operator, in 1810 Ellis was paid the high wage of $2.00 per day.The steam engine ran the saw mill and was used to manufacture anchors, chain, and steam engines for vessels of war.[7] The 1835 Washington Navy Yard labor strike was the first labor strike of federal civilian employees]].[8] The strike which was unsuccessful was from 29 July to 15 August 1835. The strike was over working conditions and in support of a ten hour day.[9]

For the first thirty years of the nineteenth century, the Navy Yard was the District's principal employer of enslaved African Americans. Their numbers rose rapidly and by 1808, the enslaved made up one third of the workforce. The number of enslaved workers gradually declined during the next thirty years, though free and some enslaved African Americans remained a vital presence. One such person was former slave later freeman Michael Shiner 1805-1880 whose diary chronicled his life and work at the navy yard for over half a century [10]

During the American Civil War, the Yard once again became an integral part of the defense of Washington. Commandant Franklin Buchanan resigned his commission to join the Confederacy, leaving the Yard to Commander John A. Dahlgren. President Abraham Lincoln, who held Dahlgren in the highest esteem, was a frequent visitor. The famous ironclad USS Monitor was repaired at the Yard after her historic battle with the CSS Virginia. The Lincoln assassination conspirators were brought to the Yard following their capture. The body of John Wilkes Booth was examined and identified on the monitor USS Montauk, moored at the Yard.

Following the war, the Yard continued to be the scene of technological advances. In 1886, the Yard was designated the manufacturing center for all ordnance in the Navy. Commander Theodore F. Jewell was Superintendent of the Naval Gun Factory from January 1893 to February 1896. Ordnance production continued as the Yard manufactured armament for the Great White Fleet and the World War I navy. The 14-inch (360 mm) naval railway guns used in France during World War I were manufactured at the Yard.

By World War II, the Yard was the largest naval ordnance plant in the world. The weapons designed and built there were used in every war in which the United States fought until the 1960s. At its peak, the Yard consisted of 188 buildings on 126 acres (0.5 km²) of land and employed nearly 25,000 people. Small components for optical systems, and enormous 16-inch (410 mm) battleship guns were all manufactured here. In December 1945, the Yard was renamed the U.S. Naval Gun Factory. Ordnance work continued for some years after World War II until finally phased out in 1961. Three years later, on July 1, 1964, the activity was re-designated the Washington Navy Yard. The deserted factory buildings began to be converted to office use.[11] In 1963, ownership of 55 acres of the Washington Navy Yard Annex (western side of Yard including Building 170) was transferred to the General Services Administration.[12] The Yards at the Southeast Federal Center are part of this former property and now includes the headquarters for the United States Department of Transportation.[13]

The Washington Navy Yard was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973, and designated a National Historic Landmark on May 11, 1976.[11][14] It is part of the Capitol Riverfront Business Improvement District. It is also part of the Navy Yard, also known as Near Southeast, neighborhood. It is served by the Navy Yard – Ballpark Metro station on the Green Line.

The Marine Corps Museum was located on the first floor of the Marine Corps Historical Society in Building 58. The museum closed on July 1, 2005 during the establishment of the National Museum of the Marine Corps near Marine Corps Base Quantico. The Yard was headquarters to the Marine Corps Historical Center. That moved in 2006 to Quantico.

Cultural and scientific

The Washington Navy Yard was the scene of many scientific developments. Robert Fulton conducted research and testing on his clockwork torpedo during the War of 1812. In 1822, Commodore John Rodgers built the country's first marine railway for the overhaul of large vessels. John A. Dahlgren developed his distinctive bottle-shaped cannon that became the mainstay of naval ordnance before the Civil War. In 1898, David W. Taylor developed a ship model testing basin, which was used by the Navy and private shipbuilders to test the effect of water on new hull designs. The first shipboard aircraft catapult was tested in the Anacostia River in 1912, and a wind tunnel was completed at the Yard in 1916. The giant gears for the Panama Canal locks were cast at the Yard. Navy Yard technicians applied their efforts to medical designs for prosthetic hands and molds for artificial eyes and teeth.

Navy Yard was Washington's earliest industrial neighborhood. One of the earliest industrial buildings nearby was the eight-story brick Sugar House, built in Square 744 at the foot of New Jersey Avenue, SE as a sugar refinery in 1797-98. In 1805, it became the Washington Brewery, which produced beer until it closed in 1836. The brewery site was just west of the Washington City Canal in what is now Parking Lot H/I in the block between Nationals Park and the historic DC Water pumping station.[15]

The Washington Navy Yard was the ceremonial gateway to the nation's capital. In 1860, the first Japanese diplomatic mission was welcomed to the United States in an impressive pageant at the Yard. The body of World War I's Unknown Soldier was received here. Charles A. Lindbergh returned to the Navy Yard in 1927 after his famous transatlantic flight.

During the Civil War a small number of women worked at the Navy Yard as flag makers and seamstresses sewing canvas bags for gun powder.[16] Women again entered the workforce in the twentieth century in significant numbers during WWII, where they worked at the Naval Gun Factory making munitions.[16] Following the war most were discharged,[16] but gradually women have increased their presence in executive, managerial, administrative, technical and clerical positions.

From 1984 to 2015, the decommissioned destroyer USS Barry (DD-933) was a museum ship at the Washington Navy Yard as "Display Ship Barry" (DS Barry). Barry was frequently used for change of command ceremonies for naval commands in the area.[11] Due to declining visitors to the ship, the expensive renovations she required, and the District's plans to build a new bridge that would trap her in the Anacostia River, Barry was towed away during the winter of 2015-2016 for scrapping.[17] The U.S. Navy held an official departure ceremony for the ship on 17 October 2015.[18][19][20]

Today, the Navy Yard houses a variety of activities. It serves as headquarters, Naval District Washington, and houses numerous support activities for the fleet and aviation communities. The Navy Museum welcomes visitors to the Navy Art Collection[21] and its displays of naval art and artifacts, which trace the Navy's history from the Revolutionary War to the present day. The Naval History and Heritage Command is housed in a complex of buildings known as the Dudley Knox Center for Naval History. Leutze Park is the scene of colorful ceremonies.

2013 shooting

On September 16, 2013, a shooting took place at the Yard. Shots were fired at the headquarters for the Naval Sea Systems Command Headquarters building #197. Fifteen people, including thirteen civilians, one D.C. police officer, and one base officer, were shot. Twelve fatalities were confirmed by the United States Navy and D.C. Police.[22][23] Officials said the gunman, Aaron Alexis, a 34-year-old civilian contractor from Queens, New York, was killed during a gunfight with police.[24]

Operations

The Yard serves as a ceremonial and administrative center for the U.S. Navy, home to the Chief of Naval Operations, and is headquarters for the Naval Sea Systems Command, Naval Reactors, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Naval Historical Center, the Department of Naval History, the U.S. Navy Judge Advocate General's Corps, the United States Navy Band, the U.S. Navy's Military Sealift Command and numerous other naval commands. A number of Officers' Quarters are located at the facility.

Building 126

Building 126 is located by the Anacostia River, on the northeast corner of 11th and SE O Streets. The one-story building, built between 1925 and 1938, was recently renovated to be a net-zero energy building as part of the Washington Navy Yard Energy Demonstration Project. Features include two wind turbines, five geothermal wells, a battery energy storage system, one-hundred thirty-two 235 kW solar photovoltaic panels, and windows of electrochromic smart glass.[25]

Although inventoried and determined eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, it is currently not part of an existing district.[26] Until 1950, Building 126 functioned as the receiving station laundry. Afterward, it served as the site of the Washington Navy Yard Police Station. Currently, it acts as the Visitor Center for the Yard.[27]

Gallery

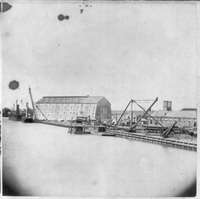

View of Washington Navy Yard's dock, circa 1867

View of Washington Navy Yard's dock, circa 1867 Experimental Model Basin, circa 1900

Experimental Model Basin, circa 1900 Torpedo shop at the Washington Navy Yard, circa 1917

Torpedo shop at the Washington Navy Yard, circa 1917 The Unknown Soldier from World War I arriving at the Washington Navy Yard, circa 1921 (coloured)

The Unknown Soldier from World War I arriving at the Washington Navy Yard, circa 1921 (coloured)_berthed_at_Washington_Navy_Yard.jpg) An aerial view of the destroyer USS Barry (DD-933) docked at the Washington Navy Yard, 15 April 1984

An aerial view of the destroyer USS Barry (DD-933) docked at the Washington Navy Yard, 15 April 1984

See also

- Arsenal Point

- Building 170

- List of National Historic Landmarks in the District of Columbia

- 1835 Washington Navy Yard labor strike

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ U.S. EPA. "Washington Navy Yard". Superfund Information Systems: Site Progress Profile. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ↑ Mary Stockton Hunter, The Burning of Washington, D.C. New York Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin 1924, pp 80–83.

- ↑ Sharp John G. Washington Navy Yard Station Log entries Naval History and Heritage Command https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/w/washington-navy-yard-station-log-november-1822-march-1830-extracts.html

- ↑ Sharp, John G. Washington Navy Yard Payroll 1819 -1820 of Mechanics and laborers Genealogy Trails http://genealogytrails.com/washdc/WNY/wnymechpayroll1819to1820.html

- ↑ Sharp, John G. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799 -1962 Naval History and Heritage Command 2005, pp72-76.

- ↑ Papers of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Maryland Historical Society, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984-1988 Vol.II, pp 908 – 910.

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Strike in American History editors Aron Brenner, Benjamin Daily and Emanuel Ness, (New York:M.E.Sharpe, 2009) ,.xvii.

- ↑ Maloney, Linda M. The Captain from Connecticut: The Life and Naval Times of Isaac Hull. Northeastern University Press: Boston, 1986 pp 436 - 437

- ↑ John G. Sharp, Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869 Naval History and Heritage Command 2015 Retrieved Oct. 30,2016

- 1 2 3 "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form" (PDF). National Park Service. November 1, 1975. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ↑ "Request for Determination of Eligibility to the National Register of Historic Places for the Washington Navy Yard Annex". General Services Administration. Historic American Buildings Survey. November 1976. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- ↑ "The Road to Reuse…" (PDF). General Services Administration. Environmental Protection Agency. May 2009. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ↑ "National Historic Landmarks Survey" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ↑ Peck, Garrett (2014). Capital Beer: A Heady History of Brewing in Washington, D.C. Charleston, SC: The History Press. ISBN 978-1626194410.

- 1 2 3 Sharp, John G. (2005). History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce, 1799-1962 (PDF). Washington Navy Yard: Naval District Washington. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ↑ Copper, Kyle (6 May 2016). "Museum ship at Navy Yard leaving the nation’s capital". WTOP. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ↑ Dingfelder, Sadie (September 10, 2015). "Bidding farewell to the Barry". Washington Post.

- ↑ Morris, Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Tyrell K. (October 17, 2015). "Navy Bids Farewell to Display Ship Barry". Washington: United States Navy, Chief of Information.

- ↑ Eckstein, Megan (October 19, 2015). "Washington Navy Yard Says Goodbye to Display Ship Barry". USNI News.

- ↑ Navy Art Collection web-page. Naval History & Heritage Command official website. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Washington Navy Yard shooting: Active shooter sought in Southeast D.C". WJLA TV. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

- ↑ "4 killed, 8 injured in a shooting at Washington Navy Yard". Washington Times. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

- ↑ DC Navy Yard Gunshots; September 16, 2013; CNN online; accessed .

- ↑ Miller, Kiona. "Navy Yard Visitor's Center Completes Net Zero Project". Naval District Washington. Department of the Navy. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ "11th Street Bridges Final Environmental Impact Statement" (PDF). District of Columbia Department of Transportation. Government of the District of Columbia. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ "Record of Decision for Sites 1, 2, 3, 7, 9, 11, and 13 Washington Navy Yard" (PDF). Naval Facilities Engineering Command Washington. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Washington Navy Yard. |

- Washington Navy Yard history

- "The United States Naval Gun Factory" by Commander Theodore F. Jewell, Harper's Magazine, Vol. 89, Issue 530, July 1894, pp. 251–261.

- Washington Navy Yard Walking Tour C-SPAN3, Thomas Frezza, May 2017