Natural gas transmission system of Ukraine

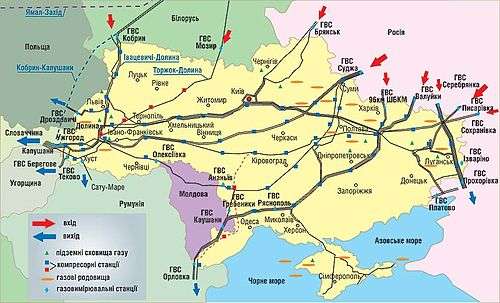

The natural gas transmission system of Ukraine is a complex of natural gas transmission pipelines for gas import and transit in Ukraine. It is one of the largest gas transmission systems in the world.[1] The system is linked with natural gas transmission systems of Russia and Belarus on one hand, and with systems of Poland, Romania, Moldova, Hungary and Slovakia on other hand.[2] The system is owned by Government of Ukraine and operated by Ukrtransgaz.[3] Some local transmission lines together with distribution sets are owned by regional gas companies.[3]

History

The development of Ukrainian gas pipeline system started in Galicia, then part of Poland.[4] The first gas pipeline was Boryslav–Drohobych pipeline in 1912. In 1924, after discovery of the Dashava gas field the Dashava–Stryi–Drohobych gas pipeline was constructed.[5] In 1928, the Dashava–Lviv and in 1937, the Dashava–Tarnów pipelines were built. After Soviet annexation of Eastern Galicia, the Dashava–Tarnów pipeline became the first cross-border pipeline of the Soviet Union.[4] the Opory–Boryslav and Opory–Lviv pipelines were built in 1940–1941.[6]

The current Ukrainian transmission system was built as an integrated part of the unified gas supply system of the former Soviet Union. In 1940–1960s, it was mainly built to use the Galician gas in other regions of the Soviet Union.[6] In 1948, the Dashava–Kyiv pipeline which was the largest pipeline that time in Europe, was launched.[5] In 1951, Dashava–Kyiv pipeline was prolonged to Bryansk and Moscow. In 1955, construction of the Dashava–Minsk pipeline started, which later was prolonged to Vilnius and Riga.[6] It was completed in 1960.[5] After discovery of the Shebelinka gas field in 1956, the Shebelinka–Kharkiv pipeline and the Shebelinka–Dnipropetrovsk–Kryvyi Rih–Odessa pipeline with branches to Zaporizhia, Mykolaiv and Kherson were completed in 1966.[6][7] This southern corridor was prolonged to Moldova and later to Southeast Europe between 1974 and 1978.[7] The Shebelinka–Kyiv pipeline with branches to Poltava and Kremenchuk was completed in 1969.[6][7] In 1970–1974, it was prolonged to the Western border.[7] Also the Shebelinka–Belgorod–Kursk–Bryansk pipelines was built.[6] In 1964, the first underground gas storage in Ukraine, the Olyshevske gas storage, was commissioned.[5]

In 1970–1980s, the Ukrainian gas transmission system was developed as a gas export route to Europe.[8] The first large-scale export pipeline, the Dolyna–Uzhhorod–Western border pipeline, became operational in 1967. It was the first stage of the Bratstvo (Brotherhood) pipeline system.[6] In 1978, the Soyuz pipeline (Orenburg–Western border pipeline) was built as the first Soviet natural gas export pipeline. It followed by the Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhhorod pipeline in 1983 (now also named as Bratstvo or Brotherhood pipeline) and the Progress pipeline (Yamburg–Western border pipeline) in 1988. Between 1986 and 2001, the Yelets–Kremenchuk–Ananyiv–Tiraspol–Izmail rote was developed.[9]

Technical description

The natural gas transmission system of Ukraine consists of 38,550 kilometres (23,950 mi) of pipelines, including 22,160 kilometres (13,770 mi) of trunk pipelines and 16,390 kilometres (10,180 mi) of branch pipelines.[10] In addition, the system includes 72 compressor stations with 702 compressors, having a total capacity of 5,442.9 MW, and 13 underground gas storage facilities with an active storage capacity of 30.9 billion cubic metres (1.09 trillion cubic feet).[3][11] As of 2009, the system had import capacity of 288 billion cubic metres (10.2 trillion cubic feet) and export capacity of 178 billion cubic metres (6.3 trillion cubic feet) per year.[11]

Before 2012, gas entered to Ukraine only from entry points on borders with Russia and Belarus. Most of the gas transit went to Slovakia and further to other countries in Central and Western Europe. Smaller amount of natural gas was transported to Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Moldova.[8] In 2012–2014, some entry/exit points with Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia were modified to allow also reverse gas flow from these countries to Ukraine.[12]

The value of the Ukrainian transmission system is estimated at US$9–25 billion. In 2004, the Ukrainian Centre for Economic and Political Studies estimated its value at $12–13 billion.[1]

Major pipelines

The gas transmission system of Ukraine could be divided into three transit corridors which are the western transit corridor, the southern transit corridor, and the north–south internal corridor for Russian domestic gas transportation.[2]

Western corridor

Main pipelines of the western corridor, also known as the Bratstvo or Brotherhood pipeline system, are the Soyuz pipeline (Orenburg–Western border pipeline), the Progress pipeline (Yamburg–Western border pipeline) and the Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhhorod pipeline. In addition, it consist of the Yelets–Kursk–Dykanka pipeline, the Kursk–Kyiv pipeline, the Kyiv–Western border pipeline, the Komarno–Drozdovychi pipeline, the Ivatsevichy–Dolyna pipeline, the Torzhok–Smolensk–Mazyr–Dolyna pipeline, the Uzhhorod–Berehove pipeline, the Dolyna–Uzhhorod pipeline, and the Khust–Satu Mare pipeline.[2][8]

The Soyuz pipeline, originating from the Orenburg gas field, enters to Ukraine east of Novopskov through the Sokhranovka gas metering station in Russia.[8] Up to Novopskov, it runs parallel to the Orenburg–Novopskov pipeline. From there, the Soyuz pipeline runs westward until near Bar it joins the corridor of the Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhhorod and Progress pipelines. It leaves Ukraine through the Uzhhorod gas metering and pumping station.[1] Length of the Ukrainian section of the Soyuz pipeline is 1,567 kilometres (974 mi) and it has capacity of 26.1 billion cubic metres (920 billion cubic feet) per year.[11]

The Progress pipeline, originating from the Yamburg gas field, runs mostly parallel to the Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhhorod pipeline. It enters to Ukraine north of Sumy through the Sudzha gas metering station in Russia and leaves through the Uzhhorod gas metering and pumping station.[1] The Ukrainian section has length of 1,120 kilometres (700 mi) and it has capacity of 28.5 billion cubic metres (1.01 trillion cubic feet) per year.[11]

The Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhhorod pipeline, originating from the Urengoy gas field, enters to Ukraine at the Sudzha gas metering station like Progress, the Kursk–Kyiv and the Yelets–Kursk–Dykanka pipelines. In Ukraine, it takes gas through to the Uzhhorod gas metering and pumping station on the Ukrainian border with Slovakia.[8][1] Length of the Ukrainian section is 1,160 kilometres (720 mi) and it has capacity of 29.7 billion cubic metres (1.05 trillion cubic feet) per year.[11]

The Yelets–Kursk–Dykanka and the Kursk–Kyiv pipeline enter to Ukraine through the Sudzha gas metering station.[8] The Torzhok–Smolensk–Mazyr–Dolyna pipeline enters Ukraine through the Mazur gas metering station and the Ivatsevichy–Dolyna pipeline enters through the Kobryn gas metering station, both in Belarus.[11][13] The Komarno–Drozdovychi pipeline enters to Poland through the Drozdovychi metering station, the Uzhhorod–Berehove pipeline enters to Hungary through the Berehove metering station, and the Khust–Satu Mare pipeline enters to Romania through the Tekove metering station.[8]

Southern corridor

Main pipelines of the southern transit corridor are the Yelets–Kremenchuk–Kryvyi Rih pipeline, the Shebelinka–Dnipropetrovsk–Kryvyi Rih–Rozdilna–Izmail pipeline, the Kremenchuk–Ananyiv–Bohorodchany pipeline, the Ananyiv–Tiraspol–Izmail pipeline, and the Rozdilna–Izmail pipeline.[2][8] The gas import pipelines are the Ostrogozhsk–Shebelinka pipeline, the Urengoy–Novopskov pipeline, the Petrovsk–Novopskov pipeline, and the Orenburg–Novopskov pipeline.[8]

The Yelets–Kremenchuk–Kryvyi Rih pipeline enters into Ukraine through the Sudzha gas metering station. Length of the Ukrainian section of this pipeline is 323 kilometres (201 mi) and it has capacity of 32 billion cubic metres (1.1 trillion cubic feet) per year. Length of the Kremenchuk–Ananyiv–Chernivtsi–Bohorodchany pipeline is 351 kilometres (218 mi) and it has capacity of 30 billion cubic metres (1.1 trillion cubic feet) per year.[11] It enters to Moldova through the Hrebenyky gas metering station and the reverse flow enters through the Oleksiyivka gas metering station. The Ananyiv–Tiraspol–Izmail pipeline enters Moldova through the Hrebenyky gas metering station, and the Shebelinka–Dnipropetrovsk–Kryvyi Rih–Izmail and the Rozdilna–Izmail pipelines enter through the Ryasnopil (Rozdilna) gas metering station.[14] After re-entering to Ukraine all three pipelines exit to Romania through the Orlivka gas metering and pumping station.[8][11] Length of the Ananyiv–Tiraspol–Izmail pipeline is 256 kilometres (159 mi) and it has capacity of 23.7 billion cubic metres (840 billion cubic feet) per year.[11]

The Ostrogozhsk–Shebelinka pipeline enters to Ukraine through the Valuyki gas metering station, the Orenburg–Novopskov pipelines enters through the Sokhranovka gas metering station, and the Urengoy–Novopskov and the Petrovsk–Novopskov enter through the Pisarevka gas metering station, all in Russia.[8]

Crimea is connected to the main gas transportations system (Shebelinka–Dnipropetrovsk–Kryvyi Rih–Rozdilna–Izmail pipeline) through the Marivka–Kherson–Crimea pipeline. In Krasnoperekopsk Raion, Crimea, one branch runs to the Hlibivske storage facility, one branch runs to Dzhankoy, Feodosia and Kerch, and one branch runs to Simferopol and Sevastopol.[15]

North–south Russian domestic corridor

This corridor, crossing Luhansk Oblast in Eastern Ukraine, consist of the Southern Caucasus–Centre pipeline system. Main pipelines of this corridor are the Krasnodar–Serpukhov pipeline and the Stavropol–Moscow pipeline, entering to Ukraine through the Prokhorivka gas metering station in south and the Serebryanka gas metering station in north. After Russia built the Sokhranovka–Oktyabrskaya bypass and the Petrovsk–Frolovo–Izobilnoye pipeline, this corridor through Ukraine is not in use.[2][16] However, during the Ukrainian crisis Russia used this corridor to supply Donbas regions not controlled by the Ukrainian Government through the Prokhorivka and Platovo gas metering stations.[17]

Underground gas storages

Ukraine has 12 gas storage operated by Ukrtransgas. Five of these are located in Western Ukraine, two in Central Ukraine and five in Eastern Ukraine.[1] In addition one gas storage, the Hlibivske storage facility, operated by Chornomornaftogaz, is located in Crimea and currently is not controlled by Ukraine authorities.[3] The largest storage is Bilche–Volytsko–Ugerske in Western Ukraine having more than half of the Ukrainian total storage capacity.[1]

Rehabilitation and modernization

In 2009, Ukraine, the European Commission, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, European Investment Bank and the World Bank signed a joint declaration on the modernisation of the Ukrainian gas transmission System. The European Union financed the feasibility study which was conducted by Mott MacDonald.[3] According to the master plan of Ukrtransgas, the priority objects are Soyuz, Progress, Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhhorod, Yelets–Kremenchuk–Kryvyi Rih and Ananyiv–Tiraspol–Izmail pipelines, Bilche–Volytsko–Ugerske and Bohorodchany underground gas storages, and Uzhhorod, Berehove, Drozdovychi, Tekove and Orlivka gas metering stations.[11] The priority investment programme requires US$3.2 billion, $342 million for storage and $2.85 billion for pipelines and compressors.[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pirani, Simon (2007). Ukraine's gas sector (PDF). Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. pp. 73–81. ISBN 9781901795639. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ministry of Energy and Coal Industry of Ukraine (2012). "Statement on security of energy supply of Ukraine" (PDF). Energy Community. pp. 29–34. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ukraine (PDF). Energy Policies Beyond IEA Countries. IEA/OECD. 2012. pp. 109–124. ISBN 9789264171510.

- 1 2 Lotysz, Slawomir. "The Dashava gas pipeline: the first Eastern European link". Inventing Europe. Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- 1 2 3 4 "Remarkable events in Ukraine's oil-gas industry". Naftogaz Europe. Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Когда Россия отдаст Украине забранный у нее газ? [When Russia would give back gas taken from Ukraine?]. UArgument. 2014-12-23. Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- 1 2 3 4 Heinrich, Andreas (2014). Export Pipelines from the CIS Region: Geopolitics, Securitization, and Political Decision-Making. Changing Europe. 10. Columbia University Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 9783838265391.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Korchemkin, Mikhail (2009-01-16). "Gazprom insists on using just one specific pipeline". East European Gas Analysis. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- ↑ Ukrtransgaz (2011). "Ukrainian Gas Transmission System (UGTS). Modernisation and Reconstruction" (PDF). The Energy Exchange. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- ↑ "Trunk gas pipelines". Ukrtransgaz. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Naftogaz (2009). "Master Plan. Ukrainian Gas Transmission System (UGTS). Priority Objects. Modernisation and Reconstruction" (PDF). Energy Charter Secretariat. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- ↑ Harrison, Colin; Princova, Zuzana (2015-10-29). "A quiet gas revolution in Central and Eastern Europe". Energy Post. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- ↑ "Naftogaz Accuses Gazprom of Slashing Gas Deliveries to Ukraine". Oil&Gas Eurasia. 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- ↑ Energy Institute Hrvoje Požar (2013). "Study on the Implementation of the Regulation (EU)994/2010 concerning measures to safeguard security of gas supply in the Energy Community" (PDF). Energy Community. p. 238. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- ↑ "РФ поставит в замерзающий Геническ до 20 тыс кубов газа в сутки" [RF puts in freezing Henichesk up to 20 thousand cubic meters of gas per day] (in Russian). Prime. 2016-01-04. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- ↑ Korchemkin, Mikhail (2007-11-21). "Gazprom inaugurates the least important pipeline project". East European Gas Analysis. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- ↑ Chi-Kong Chyong (2015-03-02). "Ukraine's gas "federalisation"". European Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2016-02-07.