Native American cultures in the United States

Native Americans in the United States fall into a number of distinct ethno-linguistic and territorial phyla, whose only uniting characeristic is that they were in a stage of either Mesolithic (hunter-gatherer) or Neolithic (subsistence farming) culture at the time of European contact.

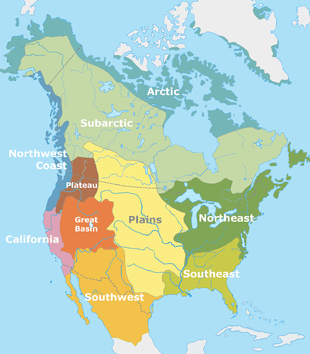

They can be classified as belonging to a number of large cultural areas:

- Continental US

- Californian tribes (Northern): Yok-Utian, Pacific Coast Athabaskan, Coast Miwok, Yurok, Palaihnihan, Chumashan, Uto-Aztecan

- Plateau tribes: Interior Salish, Plateau Penutian

- Great Basin tribes: Uto-Aztecan

- Pacific Northwest Coast: Pacific Coast Athabaskan, Coast Salish

- Southwestern tribes: Uto-Aztecan, Yuman, Southern Athabaskan

- Plains Indians: Siouan, Plains Algonquian, Southern Athabaskan

- Northeastern Woodlands tribes: Iroquoian, Central Algonquian, Eastern Algonquian

- Southeastern tribes: Muskogean, Siouan, Catawban, Iroquoian

- Alaska Natives

- Arctic: Eskimo–Aleut

- Subarctic: Northern Athabaskan

- Hawaiians

The major ethno-linguistic phyla are:

- Na-Dene languages,

- Iroquoian languages,

- Algic languages,

- Siouan–Catawban languages,

- Uto-Aztecan languages,

- Salishan languages,

- Tanoan languages

- Eskimo–Aleut (Alaska)

besides a number of language isolates and/or proposed language families such as Penutian languages, Hokan, Gulf languages and others.

Organization

Gens structure

Early European American scholars described the Native Americans (as well as any other tribal society) as having a society dominated by clans or gentes (in the Roman model) before tribes were formed. There were some common characteristics:

- The right to elect its sachem and chiefs.

- The right to depose its sachem and chiefs.

- The obligation not to marry in the gens.

- Mutual rights of inheritance of the property of deceased members.

- Reciprocal obligations of help, defense, and redress of injuries.

- The right to bestow names on its members.

- The right to adopt strangers into the gens.

- Common religious rights, query.

- A common burial place.

- A council of the gens.[1]

Tribal structure

Subdivision and differentiation took place between various groups. Upwards of forty stock languages developed in North America, with each independent tribe speaking a dialect of one of those languages. Some functions and attributes of tribes are:

- The possession of the gentes.

- The right to depose these sachems and chiefs.

- The possession of a religious faith and worship.

- A supreme government consisting of a council of chiefs.

- A head-chief of the tribe in some instances.[1]

Society and art

The Iroquois, living around the Great Lakes and extending east and north, used strings or belts called wampum that served a dual function: the knots and beaded designs mnemonically chronicled tribal stories and legends, and further served as a medium of exchange and a unit of measure. The keepers of the articles were seen as tribal dignitaries.[2]

Pueblo peoples crafted impressive items associated with their religious ceremonies. Kachina dancers wore elaborately painted and decorated masks as they ritually impersonated various ancestral spirits. Sculpture was not highly developed, but carved stone and wood fetishes were made for religious use. Superior weaving, embroidered decorations, and rich dyes characterized the textile arts. Both turquoise and shell jewelry were created, as were high-quality pottery and formalized pictorial arts.

Navajo spirituality focused on the maintenance of a harmonious relationship with the spirit world, often achieved by ceremonial acts, usually incorporating sandpainting. The colors—made from sand, charcoal, cornmeal, and pollen—depicted specific spirits. These vivid, intricate, and colorful sand creations were erased at the end of the ceremony. The Eastern Woodland Indians used the hoe.

Agriculture

An early crop the Native Americans grew was squash. Others early crops included cotton, sunflower, pumpkins, tobacco, goosefoot, knotgrass, and sump weed.

Agriculture in the southwest started around 4,000 years ago when traders brought cultigens from Mexico. Due to the varying climate, some ingenuity was needed for agriculture to be successful. The climate in the southwest ranged from cool, moist mountains regions, to dry, sandy soil in the desert. Some innovations of the time included irrigation to bring water into the dry regions and the selection of seed based on the traits of the growing plants that bore them. In the southwest, they grew beans that were self-supported, much like the way they are grown today.

In the east, however, they were planted right by corn in order for the vines to be able to "climb" the cornstalks. The most important crop the Native Americans raised was maize. It was first started in Mesoamerica and spread north. About 2,000 years ago it reached eastern America. This crop was important to the Native Americans because it was part of their everyday diet; it could be stored in underground pits during the winter, and no part of it was wasted. The husk was made into art crafts, and the cob was used as fuel for fires. By 800 CE the Native Americans had established three main crops — beans, squash, and corn — called the three sisters.

The agriculture gender roles of the Native Americans varied from region to region. In the southwest area, men prepared the soil with hoes. The women were in charge of planting, weeding, and harvesting the crops. In most other regions, the women were in charge of doing everything, including clearing the land. Clearing the land was an immense chore since the Native Americans rotated fields frequently. There is a tradition that Squanto showed the Pilgrims in New England how to put fish in fields to act like a fertilizer, but the truth of this story is debated.

Native Americans did plant beans next to corn; the beans would replace the nitrogen which the corn took from the ground, as well as using corn stalks for support for climbing. Native Americans used controlled fires to burn weeds and clear fields; this would put nutrients back into the ground. If this did not work, they would simply abandon the field to let it be fallow, and find a new spot for cultivation.

Europeans in the eastern part of the continent observed that Natives cleared large areas for cropland. Their fields in New England sometimes covered hundreds of acres. Colonists in Virginia noted thousands of acres under cultivation by Native Americans.[3]

Native Americans commonly used tools such as the hoe, maul, and dibber. The hoe was the main tool used to till the land and prepare it for planting; then it was used for weeding. The first versions were made out of wood and stone. When the settlers brought iron, Native Americans switched to iron hoes and hatchets. The dibber was a digging stick, used to plant the seed. Once the plants were harvested, women prepared the produce for eating. They used the maul to grind the corn into mash. It was cooked and eaten that way or baked as corn bread.[4]

Religion

Traditional Native American ceremonies are still practiced by many tribes and bands, and the older theological belief systems are still held by many of the "traditional" people. These spiritualities may accompany adherence to another faith, or can represent a person's primary religious identity. While much Native American spiritualism exists in a tribal-cultural continuum, and as such cannot be easily separated from tribal identity itself, certain other more clearly defined movements have arisen among "traditional" Native American practitioners, these being identifiable as "religions" in the prototypical sense familiar in the industrialized Western world.

Traditional practices of some tribes include the use of sacred herbs such as tobacco, sweetgrass or sage. Many Plains tribes have sweatlodge ceremonies, though the specifics of the ceremony vary among tribes. Fasting, singing and prayer in the ancient languages of their people, and sometimes drumming are also common.

The Midewiwin Lodge is a traditional medicine society inspired by the oral traditions and prophesies of the Ojibwa (Chippewa) and related tribes.

Another significant religious body among Native peoples is known as the Native American Church. It is a syncretistic church incorporating elements of Native spiritual practice from a number of different tribes as well as symbolic elements from Christianity. Its main rite is the peyote ceremony. Prior to 1890, traditional religious beliefs included Wakan Tanka. In the American Southwest, especially New Mexico, a syncretism between the Catholicism brought by Spanish missionaries and the native religion is common; the religious drums, chants, and dances of the Pueblo people are regularly part of Masses at Santa Fe's Saint Francis Cathedral.[5] Native American-Catholic syncretism is also found elsewhere in the United States. (e.g., the National Kateri Tekakwitha Shrine in Fonda, New York and the National Shrine of the North American Martyrs in Auriesville, New York).

The eagle feather law (Title 50 Part 22 of the Code of Federal Regulations) stipulates that only individuals of certifiable Native American ancestry enrolled in a federally recognized tribe are legally authorized to obtain eagle feathers for religious or spiritual use. The law does not allow Native Americans to give eagle feathers to non-Native Americans.

Gender roles

Gender roles were differentiated in most Native American tribes. Both sexes had power in decision making within the tribe. Many tribes, such as the Haudenosaunee Five Nations and the Southeast Muskogean tribes, had matrilineal systems, in which property and hereditary leadership were controlled by and passed through the maternal lines. The children were considered to belong to the mother's clan and achieved status within it. When the tribe adopted war captives, the children became part of their mother's clan and accepted in the tribe. In Cherokee and other matrilineal cultures, wives owned the family property. When young women married, their husbands joined them in their mother's household. This enabled the young women to have assistance for childbirth and rearing; it also protected her in case of conflicts between the couple. If they separated or the man was killed at war, the woman had her family to assist her. In addition, in matrilineal culture, the mother's brother was the leading male figure in a male child's life, as he mentored the child within the mother's clan. The husband had no standing in his wife's and children's clan, as he belonged to his own mother's clan. Hereditary clan chief positions passed through the mother's line. Chiefs were selected on recommendation of women elders, who also could disapprove of a chief. There were sometimes hereditary roles for men called peace chiefs, but war chiefs were selected based on proven prowess in battle. Men usually had the roles of hunting, waging war, and negotiating with other tribes, including the Europeans after their arrival.

Others were patriarchal, although several different systems were in use. In the patrilineal tribes, such as the Omaha, Osage and Ponca, hereditary leadership passed through the male line, and children were considered to belong to the father and his clan. For this reason, when Europeans or American men took wives from such tribes, their children were considered "white" like their fathers, or "half-breeds". Generally such children could have no official place in the tribe because their fathers did not belong to it, unless they were adopted by a male and made part of his family.[6]

Men hunted, traded and made war. The women had primary responsibility for the survival and welfare of the families (and future of the tribe); they gathered and cultivated plants, used plants and herbs to treat illnesses, cared for the young and the elderly, made all the clothing and instruments, and processed and cured meat and skins from the game. They tanned hides to make clothing as well as bags, saddle cloths, and tepee covers. Mothers used cradleboards to carry an infant while working or traveling.[7]

At least several dozen tribes allowed polygyny to sisters, with procedural and economic limits.[1]

Apart from making homes, women had many additional tasks that were also essential for the survival of the tribes. They made weapons and tools, took care of the roofs of their homes and often helped their men hunt bison.[8] In some of the Plains Indian tribes, medicine women gathered herbs and cured the ill.[9]

The Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota girls were encouraged to learn to ride, hunt and fight.[10] Though fighting was mostly left to the boys and men, occasionally women fought with them, especially if the tribe was severely threatened.[11]

Sports

Native American leisure time led to competitive individual and team sports. Jim Thorpe, Joe Hipp, Notah Begay III, Jacoby Ellsbury, and Billy Mills are well known professional athletes.

Team based

Native American ball sports, sometimes referred to as lacrosse, stickball, or baggataway, was often used to settle disputes, rather than going to war, as a civil way to settle potential conflict. The Choctaw called it isitoboli ("Little Brother of War");[12] the Onondaga name was dehuntshigwa'es ("men hit a rounded object"). There are three basic versions, classified as Great Lakes, Iroquoian, and Southern.[13]

The game is played with one or two rackets/sticks and one ball. The object of the game is to land the ball on the opposing team's goal (either a single post or net) to score and to prevent the opposing team from scoring on your goal. The game involves as few as 20 or as many as 300 players with no height or weight restrictions and no protective gear. The goals could be from around 200 feet (61 m) apart to about 2 miles (3.2 km); in Lacrosse the field is 110 yards (100 m). A Jesuit priest referenced stickball in 1729, and George Catlin painted the subject.

Individual

Chunkey was a game that consisted of a disk shaped stone that was about 1–2 inches in diameter. The disk was thrown down a 200-foot (61 m) corridor so that it could roll past the players at great speed. The disk would roll down the corridor, and players would throw wooden shafts at the moving disk. The object of the game was to strike the disk or prevent your opponents from hitting it.

Music and art

Traditional Native American music is almost entirely monophonic, but there are notable exceptions. Native American music often includes drumming and/or the playing of rattles or other percussion instruments but little other instrumentation. Flutes and whistles made of wood, cane, or bone are also played, generally by individuals, but in former times also by large ensembles (as noted by Spanish conquistador de Soto). The tuning of modern flutes is typically pentatonic.

Performers with Native American parentage have occasionally appeared in American popular music, such as Robbie Robertson (The Band), Rita Coolidge, Wayne Newton, Gene Clark, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Blackfoot, Tori Amos, Redbone, and CocoRosie. Some, such as John Trudell, have used music to comment on life in Native America, and others, such as R. Carlos Nakai integrate traditional sounds with modern sounds in instrumental recordings, whereas the music by artist Charles Littleleaf is derived from ancestral heritage and nature. A variety of small and medium-sized recording companies offer an abundance of recent music by Native American performers young and old, ranging from pow-wow drum music to hard-driving rock-and-roll and rap.

The most widely practiced public musical form among Native Americans in the United States is that of the pow-wow. At pow-wows, such as the annual Gathering of Nations in Albuquerque, New Mexico, members of drum groups sit in a circle around a large drum. Drum groups play in unison while they sing in a native language and dancers in colorful regalia dance clockwise around the drum groups in the center. Familiar pow-wow songs include honor songs, intertribal songs, crow-hops, sneak-up songs, grass-dances, two-steps, welcome songs, going-home songs, and war songs. Most indigenous communities in the United States also maintain traditional songs and ceremonies, some of which are shared and practiced exclusively within the community.[14]

Native American art comprises a major category in the world art collection. Native American contributions include pottery, paintings, jewellery, weavings, sculpture, basketry, and carvings. Franklin Gritts was a Cherokee artist who taught students from many tribes at Haskell Institute (now Haskell Indian Nations University) in the 1940s, the Golden Age of Native American painters. The integrity of certain Native American artworks is protected by an act of Congress that prohibits representation of art as Native American when it is not the product of an enrolled Native American artist.

Economy

Traditional economy

Iñupiat, the Inuit of Alaska, prepared and buried large amounts of dried meat and fish. Pacific Northwest tribes crafted seafaring dugouts 40–50 feet (12–15 m) long for fishing. Farmers in the Eastern Woodlands tended fields of maize with hoes and digging sticks, while their neighbors in the Southeast grew tobacco as well as food crops. On the Plains, some tribes engaged in agriculture but also planned buffalo hunts in which herds were driven over bluffs.

Dwellers of the Southwest deserts hunted small animals and gathered acorns to grind into flour with which they baked wafer-thin bread on top of heated stones. Some groups on the region's mesas developed irrigation techniques, and filled storehouses with grain as protection against the area's frequent droughts.

In the early years, as these native peoples encountered European explorers and settlers and engaged in trade, they exchanged food, crafts, and furs for blankets, iron and steel implements, horses, trinkets, firearms, and alcoholic beverages.

Slavery

The majority of Native American tribes did practice some form of slavery before the European introduction of African slavery into North America, but none exploited slave labor on a large scale. In addition, Native Americans did not buy and sell captives in the pre-colonial era, although they sometimes exchanged enslaved individuals with other tribes in peace gestures or in exchange for their own members.[15]

The conditions of enslaved Native Americans varied among the tribes. In many cases, young enslaved captives were adopted into the tribes to replace warriors killed during warfare or by disease. Other tribes practiced debt slavery or imposed slavery on tribal members who had committed crimes; but, this status was only temporary as the enslaved worked off their obligations to the tribal society.[15]

Among some Pacific Northwest tribes, about a quarter of the population were slaves.[16] Other slave-owning tribes of North America were, for example, Comanche of Texas, Creek of Georgia, the Pawnee, and Klamath.[17]

European enslavement

When Europeans arrived as colonists in North America, Native Americans changed their practice of slavery dramatically. Native Americans began selling war captives to whites rather than integrating them into their own societies as they had done before. As the demand for labor in the West Indies grew with the cultivation of sugar cane, Europeans enslaved Native Americans for the Thirteen Colonies, and some were exported to the "sugar islands." The British settlers, especially those in the southern colonies, purchased or captured Native Americans to use as forced labor in cultivating tobacco, rice, and indigo. Accurate records of the numbers enslaved do not exist. Scholars estimate tens of thousands of Native Americans may have been enslaved by the Europeans, being sold by Native Americans themselves.

Slavery became a caste of people who were foreign to the English (Native Americans, Africans and their descendants) and non-Christians. The Virginia General Assembly defined some terms of slavery in 1705:

All servants imported and brought into the Country... who were not Christians in their native Country... shall be accounted and be slaves. All Negro, mulatto and Indian slaves within this dominion ... shall be held to be real estate. If any slave resists his master ... correcting such slave, and shall happen to be killed in such correction ... the master shall be free of all punishment ... as if such accident never happened.— Virginia General Assembly declaration, 1705[18]

The slave trade of Native Americans lasted only until around 1730. It gave rise to a series of devastating wars among the tribes, including the Yamasee War. The Indian Wars of the early 18th century, combined with the increasing importation of African slaves, effectively ended the Native American slave trade by 1750. Colonists found that Native American slaves could easily escape, as they knew the country. The wars cost the lives of numerous colonial slave traders and disrupted their early societies. The remaining Native American groups banded together to face the Europeans from a position of strength. Many surviving Native American peoples of the southeast strengthened their loose coalitions of language groups and joined confederacies such as the Choctaw, the Creek, and the Catawba for protection.

Native American women were at risk for rape whether they were enslaved or not; during the early colonial years, settlers were disproportionately male. They turned to Native women for sexual relationships.[19] Both Native American and African enslaved women suffered rape and sexual harassment by male slaveholders and other white men.[19]

Contemporary barriers to economic development

Today, other than tribes successfully running casinos, many tribes struggle, as they are often located on reservations isolated from the main economic centers of the country. The estimated 2.1 million Native Americans are the most impoverished of all ethnic groups. According to the 2000 Census, an estimated 400,000 Native Americans reside on reservation land. While some tribes have had success with gaming, only 40% of the 562 federally recognized tribes operate casinos.[20] According to a 2007 survey by the U.S. Small Business Administration, only 1% of Native Americans own and operate a business.[21]

Native Americans rank at the bottom of nearly every social statistic: highest teen suicide rate of all minorities at 18.5 per 100,000, highest rate of teen pregnancy, highest high school drop-out rate at 54%, lowest per capita income, and unemployment rates between 50% to 90%. Many Native Americans have become urbanized to survive, moving to urban centers in the states where their reservations are, or out of state. Others have entered academic and political fields that take them away from the reservations.

The barriers to economic development on Native American reservations have been identified by Joseph Kalt[22] and Stephen Cornell[23] of the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development at Harvard University, in their report: What Can Tribes Do? Strategies and Institutions in American Indian Economic Development (2008),[24] are summarized as follows:

- Lack of access to capital.

- Lack of human capital (education, skills, technical expertise) and the means to develop it.

- Reservations lack effective planning.

- Reservations are poor in natural resources.

- Reservations have natural resources, but lack sufficient control over them.

- Reservations are disadvantaged by their distance from markets and the high costs of transportation.

Teacher with picture cards giving English instruction to Navajo day school students

Teacher with picture cards giving English instruction to Navajo day school students - Tribes cannot persuade investors to locate on reservations because of intense competition from non-Native American communities.

- The Bureau of Indian Affairs is inept, corrupt, and/or uninterested in reservation development.

- Tribal politicians and bureaucrats are inept or corrupt.

- On-reservation factionalism destroys stability in tribal decisions.

- The instability of tribal government keeps outsiders from investing. (Many tribes adopted constitutions by the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act model, with two-year terms for elected positions of chief and council members deemed too short by the authors for getting things done)

- Entrepreneurial skills and experience are scarce.

- Tribal cultures get in the way.

A major barrier to development is the lack of entrepreneurial knowledge and experience within Indian reservations. "A general lack of education and experience about business is a significant challenge to prospective entrepreneurs," was the report on Native American entrepreneurship by the Northwest Area Foundation in 2004. "Native American communities that lack entrepreneurial traditions and recent experiences typically do not provide the support that entrepreneurs need to thrive. Consequently, experiential entrepreneurship education needs to be embedded into school curricula and after-school and other community activities. This would allow students to learn the essential elements of entrepreneurship from a young age and encourage them to apply these elements throughout life.".[25] Rez Biz magazine addresses these issues.

_of_Lillian_Gross%2C_Niece_of_Susan_Sanders_(Mixed_Blood)_1906.jpg)

Interracial relations

Interracial relations between Native Americans, Europeans, and Africans is a complex issue that has been mostly neglected with "few in-depth studies on interracial relationships".[26][27] Some of the first documented cases of European/Native American intermarriage and contact were recorded in Post-Columbian Mexico. One case is that of Gonzalo Guerrero, a European from Spain, who was shipwrecked along the Yucatan Peninsula, and fathered three Mestizo children with a Mayan noblewoman. Another is the case of Hernán Cortés and his mistress La Malinche, who gave birth to another of the first multi-racial people in the Americas.[28]

Assimilation

European impact was immediate, widespread, and profound—more than any other race that had contact with Native Americans during the early years of colonization and nationhood. Europeans living among Native Americans were often called "white indians". They "lived in native communities for years, learned native languages fluently, attended native councils, and often fought alongside their native companions."[29]

Early contact was often charged with tension and emotion, but also had moments of friendship, cooperation, and intimacy.[30] Marriages took place in English, Spanish, and French colonies between Native Americans and Europeans. Given the preponderance of men among the colonists in the early years, generally European men married American Indian women.

In 1528, Isabel de Moctezuma, an heir of Moctezuma II, was married to Alonso de Grado, a Spanish Conquistador. After his death, the widow married Juan Cano de Saavedra. Together they had five children. Many heirs of Emperor Moctezuma II were acknowledged by the Spanish crown, who granted them titles including Duke of Moctezuma de Tultengo.

On April 5, 1614, Pocahontas married the Englishman John Rolfe. They had a child called Thomas Rolfe. Intimate relations among Native American and Europeans were widespread, beginning with the French and Spanish explorers and trappers. For instance, in the early 19th century, the Native American woman Sacagawea, who would help translate for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, was married to the French-Canadian trapper Toussaint Charbonneau. They had a son named Jean Baptiste Charbonneau. This was the most typical pattern among the traders and trappers.

There was fear on both sides, as the different peoples realized how different their societies were.[30] The whites regarded the Indians as "savage" because they were not Christian. They were suspicious of cultures which they did not understand.[30] The Native American author, Andrew J. Blackbird, wrote in his History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan, (1897), that white settlers introduced some immoralities into Native American tribes. Many Indians suffered because the Europeans introduced alcohol and the whiskey trade resulted in alcoholism among the people, who were alcohol-intolerant.[30]

Blackbird wrote:

"The Ottawas and Chippewas were quite virtuous in their primitive state, as there were no illegitimate children reported in our old traditions. But very lately this evil came to exist among the Ottawas-so lately that the second case among the Ottawas of 'Arbor Croche' is yet living in 1897. And from that time this evil came to be quite frequent, for immorality has been introduced among these people by evil white persons who bring their vices into the tribes."[30]

The U. S. government had two purposes when making land agreements with Native Americans: to open it up more land for white settlement,[31] and to ease tensions between whites and Native Americans by forcing Natives to use the land in the same way as did the whites - for subsistence farms.[31] The government used a variety of strategies to achieve these goals; many treaties required Native Americans to become farmers in order to keep their land.[31] Government officials often did not translate the documents which Native Americans were forced to sign, and native chiefs often had little or no idea what they were signing.[31]

For a Native American man to marry a white woman, he had to get consent of her parents, as long as "he can prove to support her as a white woman in a good home".[34] In the early 19th century, the Shawnee Tecumseh and blonde hair & blued eyed Rebbecca Galloway had an inter-racial affair. In the late 19th century, three European-American middle-class women teachers at Hampton Institute married Native American men whom they had met as students.[35]

As European-American women started working independently at missions and Indian schools in the western states, there were more opportunities for their meeting and developing relationships with Native American men. For instance, Charles Eastman, a man of European and Lakota descent whose father sent both his sons to Dartmouth College, got his medical degree at Boston University and returned to the West to practice. He married Elaine Goodale, whom he met in South Dakota. He was the grandson of Seth Eastman, a military officer from Maine, and a chief's daughter. Goodale was a young European-American teacher from Massachusetts and a reformer, who was appointed as the US superintendent of Native American education for the reservations in the Dakota Territory. They had six children together.

Relation with African Americans

African and Native Americans have interacted for centuries. The earliest record of Native American and African contact occurred in April 1502, when Spanish colonists transported the first Africans to Hispaniola to serve as slaves.[36]

Sometimes Native Americans resented the presence of African Americans.[37] The "Catawaba tribe in 1752 showed great anger and bitter resentment when an African American came among them as a trader."[37] To gain favor with Europeans, the Cherokee exhibited the strongest color prejudice of all Native Americans.[38] He contends that because of European fears of a unified revolt of Native Americans and African Americans, the colonists encouraged hostility between the ethnic groups: "Whites sought to convince Native Americans that African Americans worked against their best interests."[39] In 1751, South Carolina law stated:

"The carrying of Negroes among the Indians has all along been thought detrimental, as an intimacy ought to be avoided."[40]

In addition, in 1758 the governor of South Carolina James Glen wrote:

it has always been the policy of this government to create an aversion in them Indians to Negroes.[41]

Europeans considered both races inferior and made efforts to make both Native Americans and Africans enemies.[42] Native Americans were rewarded if they returned escaped slaves, and African Americans were rewarded for fighting in the late 19th-century Indian Wars.[42][43][44]

"Native Americans, during the transitional period of Africans becoming the primary race enslaved, were enslaved at the same time and shared a common experience of enslavement. They worked together, lived together in communal quarters, produced collective recipes for food, shared herbal remedies, myths and legends, and in the end they intermarried."[45] Because of a shortage of men due to warfare, many tribes encouraged marriage between the two groups, to create stronger, healthier children from the unions.[46]

In the 18th century, many Native American women married freed or runaway African men due to a decrease in the population of men in Native American villages.[42] Records show that many Native American women bought African men but, unknown to the European sellers, the women freed and married the men into their tribe.[42] When African men married or had children by a Native American woman, their children were born free, because the mother was free (according to the principle of partus sequitur ventrum, which the colonists incorporated into law.)[42]

European colonists often required the return of runaway slaves to be included as a provision in treaties with American Indians. In 1726, the British Governor of New York exacted a promise from the Iroquois to return all runaway slaves who had joined up with them.[47] In the mid-1760s, the government requested the Huron and Delaware to return runaway slaves, but there was no record of slaves having been returned.[48] Colonists placed ads about runaway slaves.

While numerous tribes used captive enemies as servants and slaves, they also often adopted younger captives into their tribes to replace members who had died. In the Southeast, a few Native American tribes began to adopt a slavery system similar to that of the American colonists, buying African American slaves, especially the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Creek. Though less than 3% of Native Americans owned slaves, divisions grew among the Native Americans over slavery.[49] Among the Cherokee, records show that slave holders in the tribe were largely the children of European men that had shown their children the economics of slavery.[43] As European colonists took slaves into frontier areas, there were more opportunities for relationships between African and Native American peoples.[42]

Based on the work of geneticists, a PBS series on African Americans explained that while most African Americans are racially mixed, it is relatively rare that they have Native American ancestry.[50][51] According to the PBS series, the most common "non-black" mix is English and Scots-Irish.[50][51] However, the Y-chromosome and mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA) testing processes for direct-line male and female ancestors can fail to pick up the heritage of many ancestors. (Some critics thought the PBS series did not sufficiently explain the limitations of DNA testing for assessment of heritage.)[52]

Another study suggests that relatively few Native Americans have African-American heritage.[53] A study reported in The American Journal of Human Genetics stated, "We analyzed the European genetic contribution to 10 populations of African descent in the United States (Maywood, Illinois; Detroit; New York; Philadelphia; Pittsburgh; Baltimore; Charleston, South Carolina; New Orleans; and Houston) ... mtDNA haplogroups analysis shows no evidence of a significant maternal Amerindian contribution to any of the 10 populations."[54] A few writers persist in the myth that most African Americans have Native American heritage.[55]

DNA testing has limitations and should not be depended on by individuals to answer all their questions about heritage.[52][56] So far, such testing cannot distinguish among the many distinct Native American tribes. No tribes accept DNA testing to satisfy their differing qualifications for membership, usually based on documented blood quantum or descent from ancestor(s) listed on the Dawes Rolls.[57]

Native Americans interacted with enslaved Africans and African Americans on many levels. Over time all the cultures interacted. Native Americans began slowly to adopt white culture.[42] Native Americans in the South shared some experiences with Africans, especially during the period, primarily in the 17th century, when both were enslaved. The colonists along the Atlantic Coast had begun enslaving Native Americans to ensure a source of labor. At one time the slave trade was so extensive that it caused increasing tensions with the various Algonquian tribes, as well as the Iroquois. Based in New York and Pennsylvania, they had threatened to attack colonists on behalf of the related Iroquoian Tuscarora before they migrated out of the South in the early 1700s.[45]

In the 1790s, Benjamin Hawkins was assigned as the US agent to the southeastern tribes, who became known as the Five Civilized Tribes for their adoption of numerous Anglo-European practices. He advised the tribes to take up slaveholding to aid them in European-style farming and plantations. He thought their traditional form of slavery, which had looser conditions, was less efficient than chattel slavery.[41] In the 19th century, some members of these tribes who were more closely associated with settlers, began to purchase African-American slaves for workers. They adopted some European-American ways to benefit their people.

The writer William Loren Katz contends that Native Americans treated their slaves better than did the typical European American in the Deep South.[58] Though less than 3% of Native Americans owned slaves, bondage created destructive cleavages among those who were slaveholders.

Among the Five Civilized Tribes, mixed-race slaveholders were generally part of an elite hierarchy, often based on their mothers' clan status, as the societies had matrilineal systems. As did Benjamin Hawkins, European fur traders and colonial officials tended to marry high-status women, in strategic alliances seen to benefit both sides. The Choctaw, Creek and Cherokee believed they benefited from stronger alliances with the traders and their societies. The women's sons gained their status from their mother's families; they were part of hereditary leadership lines who exercised power and accumulated personal wealth in their changing Native American societies. The historian Greg O'Brien calls them the Creole generation to show that they were part of a changing society. The chiefs of the tribes believed that some of the new generation of mixed-race, bilingual chiefs would lead their people into the future and be better able to adapt to new conditions influenced by European Americans.

Proposals for Indian Removal heightened the tensions of cultural changes, due to the increase in the number of mixed-race Native Americans in the South. Full bloods, who tended to live in areas less affected by colonial encroachment, generally worked to maintain traditional ways, including control of communal lands. While the traditional members often resented the sale of tribal lands to Anglo-Americans, by the 1830s they agreed it was not possible to go to war with the colonists on this issue.

Philosophy

Native American authors have written about aspects of "tribal philosophy" as opposed to the modern or Western worldview. Thus, Yankton Dakota author Vine Deloria Jr. in an essay "Philosophy and the Tribal Peoples" argued that whereas a "traditional Westerner" might reason, "Man is mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal," aboriginal thinking might read, 'Socrates is mortal, because I once met Socrates and he is a man like me, and I am mortal.'[59] Deloria explains that both of the statements assume that all men are mortal, and that these statements are not verifiable on these grounds. The line of Indian thinking, however uses empirical evidence through memory to verify that Socrates was in fact a man like the person originally making the statement, and enhances the validity of the thinking. Deloria made the distinction, "whereas the Western syllogism simply introduces a doctrine using general concepts and depends on faith in the chain of reasoning for its verification, the Indian statement would stand by itself without faith and belief."[60] Deloria also comments that Native American thinking is very specific (in the way described above) compared to the broadness of traditional Western thinking, which leads to different interpretations of basic principles. American thinkers have previously denounced Native ideas because of this narrower approach, as it leads to 'blurry' distinctions between the 'real' and the 'internal.'[61]

Despite this basic variance, what Americans classify as "classical American pragmatism," may actually have been heavily influenced by the ways of Native American thinking; according to Romano (2012), the best resource on a characteristically "Native American Philosophy" is Scott Pratt's, Native Pragmatism: Rethinking the Roots of American Philosophy, which relates the ideas of many 'American' philosophers like Pierce, James, and Dewey to important concepts in early Native thought.[62] Pratt's publication takes his readers on a journey through American philosophical history from the colonial time period, and via detailed analysis, connects the experimental nature of early American pragmatism to the empirical habit of indigenous Americans. Though Pratt makes these alliances very comprehensible, he also makes clear that the lines between the ideas of Native Americans and American philosophers are complex and historically difficult to trace.[63]

References

- 1 2 3 Morgan, Lewis H. (1907). Ancient Society. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company. pp. 70–71, 113. ISBN 0-674-03450-3.

- ↑ Iroquois History. Retrieved 2006-02-23.

- ↑ Krech III, Shepard (1999). The ecological Indian: myth and history (1 ed.). New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 107. ISBN 0-393-04755-5.

- ↑ "American Indian Agriculture". Answers.com. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- ↑ A Brief History of the Native American Church by Jay Fikes. Retrieved 2006-02-22.

- ↑ Melvin Randolph Gilmore, "The True Logan Fontenelle", Publications of the Nebraska State Historical Society, Vol. 19, edited by Albert Watkins, Nebraska State Historical Society, 1919, p. 64, at GenNet, accessed 2011-08-25

- ↑ Beatrice Medicine, "Gender", Encyclopedia of North American Indians, February 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Native American Women", Indians.org. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- ↑ "Medicine Women" Archived 2012-06-18 at the Wayback Machine., Bluecloud.org. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- ↑ Zinn, Howard (2005). A People's History of the United States: 1492–present, Harper Perennial Modern Classics. ISBN 0-06-083865-5.

- ↑ "Women in Battle" Archived 2012-06-18 at the Wayback Machine., Bluecloud.org. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- ↑ "Choctaw Indians". 2006. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ↑ Thomas Vennum Jr., author of American Indian Lacrosse: Little Brother of War (2002–2005). "History of Native American Lacrossee". Archived from the original on 2009-04-11. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ↑ Bierhosrt, John (1992). A Cry from the Earth: Music of North American Indians. Ancient City Press.

- 1 2 Tony Seybert (2009). "Slavery and Native Americans in British North America and the United States: 1600 to 1865" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ "Slavery in Historical Perspective". Digital History, University of Houston.

- ↑ "Slave-owning societies". Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History.

- ↑ "The Terrible Transformation:From Indentured Servitude to Racial Slavery". PBS. 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-07.

- 1 2 Gloria J. Browne-Marshall (2009). ""The Realities of Enslaved Female Africans in America", excerpted from Failing Our Black Children: Statutory Rape Laws, Moral Reform and the Hypocrisy of Denial". University of Daytona. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ "NIGA: Indian Gaming Facts". Archived from the original on 2013-03-02.

- ↑ "Number of U.S. Minority Owned Businesses Increasing".

- ↑ Kalt, Joseph. "Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development". Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ↑ Cornell, Stephen. "Co-director, Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development". Archived from the original on 2008-06-19. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ↑ Cornell, S., Kalt, J. "What Can Tribes Do? Strategies and Institutions in American Indian Economic Development" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ↑ "Native Entrepreneurship: Challenges and opportunities for rural communities — CFED, Northwest Area Foundation December 2004".

- ↑ Mary A. Dempsey (1996). "The Indian connection". American Visions. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ↑ Katherine Ellinghaus (2006). Taking assimilation to heart. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1829-1.

- ↑ "Sexuality and the Invasion of America: 1492–1806". Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ "Sharing Choctaw History". A First Nations Perspective, Galafilm. Archived from the original on December 26, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Native Americans: Early Contact". Students on Site. Archived from the original on 2008-05-10. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- 1 2 3 4 "Native Americans: Early Contact". Students on Site. Archived from the original on 2008-05-10. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ "Indian Achievement Award". Ipl.org. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "Charles A. Eastman". Answers.com. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ Ellinghaus, Katherine (2006). Taking assimilation to heart. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1829-1.

- ↑ "Virginia Magazine of History and Biography". Virginia Historical Society. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ Muslims in American History : A Forgotten Legacy by Dr. Jerald F. Dirks. ISBN 1-59008-044-0 p. 204.

- 1 2 Red, White, and Black, p. 99. ISBN 0-8203-0308-9.

- ↑ Red, White, and Black, p. 99, ISBN 0-8203-0308-9.

- ↑ Red, White, and Black, p. 105, ISBN 0-8203-0308-9.

- ↑ ColorQ (2009). "Black Indians (Afro-Native Americans)". ColorQ. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- 1 2 Tiya Miles (2008). Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom. University of California Press. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dorothy A. Mays (2008). Women in early America. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-429-5. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- 1 2 Art T. Burton (1996). "CHEROKEE SLAVE REVOLT OF 1842". LWF COMMUNICATIONS. Archived from the original on 2009-09-29. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ Fay A. Yarbrough (2007). Race and the Cherokee Nation. Univ of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4056-6. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- 1 2 National Park Service (May 30, 2009). "African American Heritage and Ethnography: Work, Marriage, Christianity". National Park Service.

- ↑ Nomad Winterhawk (1997). "Black Indians want a place in history". Djembe Magazine. Archived from the original on 2009-07-14. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ Katz WL 1997 p. 103.

- ↑ Katz WL 1997 p. 104.

- ↑ William Loren Katz (2008). "Africans and Indians: Only in America". William Loren Katz. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- 1 2 "DNA Testing: review, African American Lives, About.com". Archived from the original on March 13, 2009.

- 1 2 "African American Lives 2".

- 1 2 Troy Duster (2008). "Deep Roots and Tangled Branches". Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ Esteban Parra; et al. "Estimating African American Admixture Proportions by Use of Population-Specific Alleles". American Journal of Human Genetics.

- ↑ "Estimating African American Admixture Proportions by Use of Population". The American Journal of Human Genetics.

- ↑ Sherrel Wheeler Stewart (2008). "More Blacks are Exploring the African-American/Native American Connection". BlackAmericaWeb.com. Archived from the original on June 30, 2009. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ↑ ScienceDaily (2008). "Genetic Ancestral Testing Cannot Deliver On Its Promise, Study Warns". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ Brett Lee Shelton; J.D. and Jonathan Marks (2008). "Genetic Markers Not a Valid Test of Native Identity". Counsel for Responsible Genetics. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ William Loren Katz (2008). "Africans and Indians: Only in America". William Loren Katz. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- ↑ Romano, Carlin. America the Philosophical. New York: Random House Inc., 2012. 446. Print.

- ↑ Waters, Anne. American Indian Thought. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004. 6. Print.

- ↑ Waters, Anne. American Indian Thought. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004. 6-8. Print.

- ↑ Romano, Carlin. America the Philosophical. New York: Random House Inc., 2012. 447. Print.

- ↑ Pratt, Scott. Native Pragmatism: Rethinking the Roots of American Philosophy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002. 6-10. Print.