Indian reservation

| Native American reservations | |

|---|---|

|

Also known as: Domestic Dependent Nation | |

| |

| Category | Autonomous administrative divisions |

| Location | United States of America |

| Created | 1658 (Powhatan Tribes) |

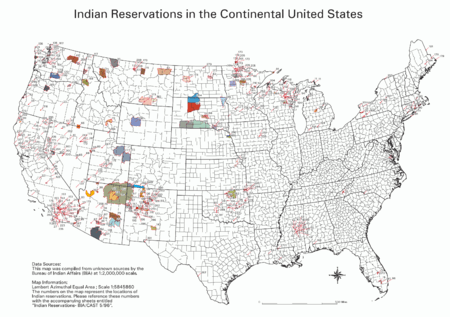

| Number | 326[1] (map includes the 310 as of May 1996) |

| Populations | 123 (several) - 173,667 (Navajo Nation)[2] |

| Areas | ranging from the 1.32-acre (0.534 hectares) Pit River Tribe's cemetery in California to the 16 million-acre (64 750 square kilometers) Navajo Nation Reservation located in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah[1] |

| Administrative divisions of the United States |

|---|

| First level |

|

|

| Second level |

|

| Third level |

|

|

| Fourth level |

| Other areas |

|

|

An Indian reservation is a legal designation for an area of land managed by a Native American tribe under the US Bureau of Indian Affairs, rather than the state governments of the United States in which they are physically located. Each of the 326[1] Indian reservations in the United States are associated with a particular Nation. Not all of the country's 567[3][4] recognized tribes have a reservation—some tribes have more than one reservation, some share reservations, while others have none. In addition, because of past land allotments, leading to some sales to non-Native Americans, some reservations are severely fragmented, with each piece of tribal, individual, and privately held land being a separate enclave. This jumble of private and public real estate creates significant administrative, political, and legal difficulties.[5]

The collective geographical area of all reservations is 56,200,000 acres (22,700,000 ha; 87,800 sq mi; 227,000 km2),[1] approximately the size of Idaho. While most reservations are small compared to US states, there are 12 Indian reservations larger than the state of Rhode Island. The largest reservation, the Navajo Nation Reservation, is similar in size to West Virginia. Reservations are unevenly distributed throughout the country; the majority are west of the Mississippi River and occupy lands that were first reserved by treaty or 'granted' from the public domain.[6]

Because tribes possess tribal sovereignty, even though it is limited, laws on tribal lands vary from the surrounding area.[7] These laws can permit legal casinos on reservations, for example, which attract tourists. The tribal council, not the local government nor the United States federal government, often has jurisdiction over reservations. Different reservations have different systems of government, which may or may not replicate the forms of government found outside the reservation. Most Native American reservations were established by the federal government; a limited number, mainly in the East, owe their origin to state recognition.[8]

The name "reservation" comes from the conception of the Native American tribes as independent sovereigns at the time the U.S. Constitution was ratified. Thus, the early peace treaties (often signed under duress) in which Native American tribes surrendered large portions of land to the U.S. also designated parcels which the tribes, as sovereigns, "reserved" to themselves, and those parcels came to be called "reservations."[9] The term remained in use even after the federal government began to forcibly relocate tribes to parcels of land to which they had no historical connection.

A majority of Native Americans and Alaska Natives live somewhere other than the reservations, often in big western cities such as Phoenix and Los Angeles.[10][11] In 2012, there were over 2.5 million Native Americans with about 1 million living on reservations.[12]

History

Colonial and early US history

From the beginning of the European colonization of the Americas, Europeans often removed native peoples from lands they wished to occupy. The means varied, including voluntary moves based on mutual agreement, treaties made under considerable duress, forceful ejection, and violence. The removal caused many problems such as tribes losing means of livelihood by being subjected to a defined area, farmers having inadmissible land for agriculture, and hostility between tribes.[13]

In 1764 the “Plan for the Future Management of Indian Affairs” was proposed by the Board of Trade.[14] Although never adopted formally, the plan established the imperial government’s expectation that land would only be bought by colonial governments, not individuals, and that land would only be purchased at public meetings.[14] Additionally, this plan dictated that the Indians would be properly consulted when ascertaining and defining the boundaries of colonial settlement.[14]

For much of North America, the American Revolution was more of a battle against the Indians than a war against the British.[14] So when the war was brought to an end with the 1783 Treaty of Paris, the treaty was generally understood by American officials to strip the Indians of all property rights east of the Mississippi River.[14] The treaty was seen by Americans as a confirmation of their conquest of Indian land.[14]

The private contracts that once characterized the sale of Indian land to various individuals and groups— from farmers to towns— were replaced by treaties between sovereigns.[14] This protocol was adopted by the United States Government after the American Revolution.[14]

On March 11, 1824, John C. Calhoun founded the Office of Indian Affairs (now the Bureau of Indian Affairs) as a division of the United States Department of War (now the United States Department of Defense), to solve the land problem with 38 treaties with American Indian tribes.[15]

Rise of Indian removal policy (1830–1868)

The passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 marked the systematization of a US federal government policy of forcibly moving Native populations away from European-populated areas.

One example was the Five Civilized Tribes, who were removed from their native lands in the southern United States and moved to modern-day Oklahoma, in a mass migration that came to be known as the Trail of Tears. Some of the lands these tribes were given to inhabit following the removals eventually became Indian Reservations.

In 1851, the United States Congress passed the Indian Appropriations Act which authorized the creation of Indian reservations in modern-day Oklahoma. Relations between settlers and natives had grown increasingly worse as the settlers encroached on territory and natural resources in the West.[16]

Forced assimilation (1868–1887)

In 1868, President Ulysses S. Grant pursued a "Peace Policy" as an attempt to avoid violence.[17] The policy included a reorganization of the Indian Service, with the goal of relocating various tribes from their ancestral homes to parcels of lands established specifically for their inhabitation. The policy called for the replacement of government officials by religious men, nominated by churches, to oversee the Indian agencies on reservations in order to teach Christianity to the native tribes. The Quakers were especially active in this policy on reservations.[18]

The policy was controversial from the start. Reservations were generally established by executive order. In many cases, white settlers objected to the size of land parcels, which were subsequently reduced. A report submitted to Congress in 1868 found widespread corruption among the federal Native American agencies and generally poor conditions among the relocated tribes.

Many tribes ignored the relocation orders at first and were forced onto their limited land parcels. Enforcement of the policy required the United States Army to restrict the movements of various tribes. The pursuit of tribes in order to force them back onto reservations led to a number of Native American massacres and some wars. The most well-known conflict was the Sioux War on the northern Great Plains, between 1876 and 1881, which included the Battle of Little Bighorn. Other famous wars in this regard included the Nez Perce War.

By the late 1870s, the policy established by President Grant was regarded as a failure, primarily because it had resulted in some of the bloodiest wars between Native Americans and the United States. By 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes began phasing out the policy, and by 1882 all religious organizations had relinquished their authority to the federal Indian agency.

Individualized reservations (1887–1934)

In 1887, Congress undertook a significant change in reservation policy by the passage of the Dawes Act, or General Allotment (Severalty) Act. The act ended the general policy of granting land parcels to tribes as-a-whole by granting small parcels of land to individual tribe members. In some cases, for example, the Umatilla Indian Reservation, after the individual parcels were granted out of reservation land, the reservation area was reduced by giving the excess land to white settlers. The individual allotment policy continued until 1934 when it was terminated by the Indian Reorganization Act.

Indian New Deal (1934–present)

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, also known as the Howard-Wheeler Act, was sometimes called the Indian New Deal. It laid out new rights for Native Americans, reversed some of the earlier privatization of their common holdings, and encouraged tribal sovereignty and land management by tribes. The act slowed the assignment of tribal lands to individual members and reduced the assignment of 'extra' holdings to nonmembers.

For the following 20 years, the U.S. government invested in infrastructure, health care, and education on the reservations. Likewise, over two million acres (8,000 km²) of land were returned to various tribes. Within a decade of John Collier's retirement (the initiator of the Indian New Deal) the government's position began to swing in the opposite direction. The new Indian Commissioners Myers and Emmons introduced the idea of the "withdrawal program" or "termination", which sought to end the government's responsibility and involvement with Indians and to force their assimilation.

The Indians would lose their lands but be compensated (though many were not). Even though discontent and social rejection killed the idea before it was fully implemented, five tribes were terminated: the Coushatta, Ute, Paiute, Menominee and Klamath, and 114 groups in California lost their federal recognition as tribes. Many individuals were also relocated to cities, but one-third returned to their tribal reservations in the decades that followed.

Land tenure and federal Indian law

With the establishment of reservations, tribal territories diminished to a fraction of original areas and indigenous customary practices of land tenure sustained only for a time, and not in every instance. Instead, the federal government established regulations that subordinated tribes to the authority, first, of the military, and then of the Bureau (Office) of Indian Affairs.[19] Under federal law, the government patented reservations to tribes, which became legal entities that at later times have operated in a corporate manner. Tribal tenure identifies jurisdiction over land use planning and zoning, negotiating (with the close participation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs) leases for timber harvesting and mining.[20]

Tribes generally have authority over other forms of economic development such as ranching, agriculture, tourism, and casinos. Tribes hire both members, other Indians and non-Indians in varying capacities; they may run tribal stores, gas stations, and develop museums (e.g., there is a gas station and general store at Fort Hall Indian Reservation, Idaho, and a museum at Foxwoods, on the Mashantucket Pequot Indian Reservation in Connecticut).[20]

Tribal members may utilize a number of resources held in tribal tenures such as grazing range and some cultivable lands. They may also construct homes on tribally held lands. As such, members are tenants-in-common, which may be likened to communal tenure. Even if some of this pattern emanates from pre-reservation tribal custom, generally the tribe has the authority to modify tenant in-common practices.

With the General Allotment Act (Dawes), 1887, the government sought to individualize tribal lands by authorizing allotments held in individual tenure.[21] Generally, the allocation process led to grouping family holdings and, in some cases, this sustained pre-reservation clan or other patterns. There had been a few allotment programs ahead of the Dawes Act. However, the vast fragmentation of reservations occurred from the enactment of this act up to 1934, when the Indian Reorganization Act was passed. However, Congress authorized some allotment programs in the ensuing years, such as on the Palm Springs/Agua Caliente Indian Reservation in California.[22]

Allotment set in motion a number of circumstances:

- individuals could sell (alienate) the allotment – under the Dawes Act, it was not to happen until after twenty-five years.

- individual allottees who would die intestate would encumber the land under prevailing state devisement laws, leading to complex patterns of heirship. Congress has attempted to mollify the impact of heirship by granting tribes the capacity to acquire fragmented allotments owing to heirship by financial grants. Tribes may also include such parcels in long-range land use planning.

- With alienation to non-Indians, their increased presence on numerous reservations has changed the demography of Indian Country. One of many implications of this fact is that tribes can not always effectively embrace the total management of a reservation, for non-Indian owners and users of allotted lands contend that tribes have no authority over lands that fall within the tax and law-and-order jurisdiction of local government.[23]

The demographic factor, coupled with landownership data, led, for example, to litigation between the Devils Lake Sioux and the State of North Dakota, where non-Indians owned more acreage than tribal members even though more Native Americans resided on the reservation than non-Indians. The court decision turned, in part, on the perception of Indian character, contending that the tribe did not have jurisdiction over the alienated allotments. In a number of instances—e.g., the Yakama Indian Reservation—tribes have identified open and closed areas within reservations. One finds the majority of non-Indian landownership and residence in the open areas and, contrariwise, closed areas represent exclusive tribal residence and related conditions.[24]

Indian Country today consists of tripartite government—i. e., federal, state and/or local, and tribal. Where state and local governments may exert some, but limited, law-and-order authority, tribal sovereignty is, of course, diminished. This situation prevails in connection with Indian gaming because federal legislation makes the state a party to any contractual or statutory agreement.[25]

Finally, other-occupancy on reservations may be by virtue of tribal or individual tenure. There are many churches on reservations; most would occupy tribal land by consent of the federal government or the tribe. BIA agency offices, hospitals, schools, and other facilities usually occupy residual federal parcels within reservations. Many reservations include one or more sections (about 640 acres) of school lands, but those lands typically remain part of the reservation (e.g., Enabling Act of 1910 at Section 20[26]). As a general practice, such lands may sit idle or be grazed by tribal ranchers.

Disputes over land sovereignty

When the Europeans discovered the New World in the fifteenth century, the land that was new to them had been home to Native Peoples for thousands of years. The American colonial government determined a precedent of establishing the land sovereignty of North America through treaties between sovereigns. This precedent was upheld by the United States government. As a result, most Native American land was purchased by the United States government, a portion of which was designated to remain under Native sovereignty. The United States government and Native Peoples do not always agree on how land should be governed, which has resulted in a series of disputes over sovereignty.

Black Hills land dispute

The Federal Government and The Lakota Sioux tribe members have been involved in sorting out a legal claim for the Black Hills since signing the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty,[27] which created what is known today as the Great Sioux Nation covering the Black Hills and nearly half of western South Dakota.[27] This treaty was acknowledged and respected until 1874, when General George Custer discovered gold,[27] sending a wave of settlers into the area and leading to the realization of the value of the land from United States President Grant.[27] President Grant used tactical military force to remove the Sioux from the land and assisted in the development of the Congressional appropriations bill for Indian Services in 1876, a "starve or sell"[28] treaty signed by only 10% of the 75% tribal men required based on specifications from the Fort Laramie Treaty[29] that relinquished the Sioux's rights to the Black Hills.[27] Following this treaty, the Agreement of 1877 was passed by Congress to remove the Sioux from the Black Hills, stating that the land was purchased from the Sioux despite the insufficient number of signatures,[27] the lack of transaction records, and the tribe's claim that the land was never for sale.[28][30]

The Black Hills are sacred to the Sioux as a place central to their spirituality and identity,[27] and contest of ownership of the land has been pressured in the courts by the Sioux Nation since they were allowed legal avenue in 1920.[27] Beginning in 1923, the Sioux made legal claim that their relinquishment from the Black Hills was illegal under the Fifth Amendment, and no amount of money can make up for the loss of their sacred land.[27] This claim went all the way up to the Supreme Court United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians case in 1979 after being revived by Congress, and the Sioux were awarded over $100 million as they ruled that the seizure of the Black Hills was in fact illegal. The Sioux have continually rejected the money, and since then the award has been accruing interest in trust accounts, and amounts to about $1 billion in 2015.[30]

During President Barack Obama’s campaign he made indications that the case of the Black Hills was going to be solved with innovate solutions and consultation,[30] but this was questioned when White House Counsel Leonard Garment sent a note to The Ogala people saying, "The days of treaty making with he American Indians ended in 1871; ...only Congress can rescind or change in any way statutes enacted since 1871." [27] The He Sapa Reparations Alliance [30] was established after Obama’s inauguration to educate the Sioux people and propose a bill to Congress that would allocate 1.3 million acres of federal land within the Black Hills to the tribe. To this day, the dispute of the Black Hills is ongoing[28] with the trust estimated to be worth nearly $1.3 billion[31] and sources believe principles of restorative justice [27] may be the best solution to addressing this century old dispute.

Iroquois land claims in Upstate New York

While 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution addressed land sovereignty disputes between the British Crown and the colonies, it neglected to settle hostilities between indigenous people— specifically those who fought on the side of the British, as four of the members of the Haudenosaunee did— and colonists.[32] In October 1784 the newly formed United States government facilitated negotiations with representatives from the Six Nations in Fort Stanwix, New York.[32] The treaty produced in 1784 resulted in Indians giving up their territory within the Ohio River Valley and the U.S. guaranteeing the Haudenosaunee six million acres— about half of what is present day New York— as permanent homelands.[32]

Unenthusiastic about the treaty’s conditions, the state of New York secured a series of twenty-six “leases,” many of them lasting 999 years on all native territories within its boundaries.[32] Led to believe that they had already lost their land to the New York Genesee Company, the Haudenosaunee agreed to land leasing which was presented by New York Governor George Clinton as a means by which the indigenous could maintain sovereignty over their land.[32] On August 28, 1788, the Oneidas leased five million acres to the state in exchange for $2,000 in cash, $2,000 in clothing, $1,000 in provisions and $600 annual rent. The other two tribes followed with similar arrangements.[32]

The Holland Land Company gained control over all but ten acres of the native land leased to the sate on September 15, 1797.[32] These 397 square miles were subsequently parceled out and subleased to whites, allegedly ending the native title to land. Despite Iroquois protests, federal authorities did virtually nothing to correct the injustice.[32] Certain of losing all of their land, in 1831 most of the Oneidas asked that what was left of their holdings be exchanged for 500,000 acres purchased from the Menominees in Wisconsin.[32] President Andrew Jackson, committed to Indian Removal west of the Mississippi, agreed.[32]

The Treaty of Buffalo Creek, signed on January 15, 1838, directly ceded 102,069 acres of Seneca land to the Ogden company for $202,000, a sum that was divided evenly between the government— to hold in trust for Indians— and non-Indian individuals who wanted to buy and improve the plots.[32] All that was left of the Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga and Tuscarora holding was extinguished at a total cost of $400,000 to Ogden.[32]

After Indian complaints, a second Treaty of Buffalo was written in 1842 in attempts to mediate tension.[32] Under this treaty the Haudenosaunee were given the right to reside in New York and small areas of reservations were restored by the U.S. government.[32]

These agreements were largely ineffective in protecting Native American land. By 1889 eighty percent of all Iroquois reservation land in New York was leased by non-Natives.[32]

Navajo-Hopi land dispute

The modern-day Navajo and Hopi Indian Reservations are located in Northern Arizona, near the Four Corners area. The Hopi reservation is 2,531.773 square miles [33] within Arizona and lies surrounded by the greater Navajo reservation which spans 27,413 square miles [34] and extends slightly into the states of New Mexico and Utah. The Hopi, also known as the Pueblo people, made many spiritually motivated migrations throughout the Southwest before settling in present-day Northern Arizona.[35] The Navajo people also migrated throughout western North America following spiritual commands before settling near the Grand Canyon area. The two tribes peacefully coexisted and even traded and exchanged ideas with each other; However, their way of lives were threatened when the “New people”, what the Navajo called white settlers,[36] began executing Natives across the continent and claiming their land, as a result of Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act. War ensued between the Navajo people, who call themselves the Diné, and new Americans. The end result was the Long Walk in the early 1860s in which the entire tribe was forced to walk roughly 400 miles from Fort Canby (present day Window Rock, Arizona) to Bosque Redondo in New Mexico. This march is similar to the well known Cherokee “Trail of Tears” and like it, many tribe did not survive the trek. The roughly 11,000 tribe members were imprisoned here in what the United States government deemed an experimental Indian reservation that failed because it became too expensive, there were too many people to feed, and they were continuously raided by other native tribe.[37] Consequently, in 1868, the Navajo were allowed to return to their homeland after signing the Treaty of Bosque Redondo. The treaty officially established the “Navajo Indian Reservation” in Northern Arizona.[34] The term reservation is one which creates territorialities or claims on places. This treaty gave them the right to the land and semi-autonomous governance of it. The Hopi reservation, on the other hand, was created through an executive order by President Arthur in 1882.[33]

A few years after the two reservations were established, the Dawes Allotment Act was passed under which communal tribal land was divvied up and allocated to each household in attempt to enforce European-American farming styles where each family owns and works their own plot of land. This was a further act of enclosure by the US government. Each family received 640 acres or less and the remaining land was deemed “surplus” because it was more than the tribes needed. This “surplus” land was then made available for purchase by American citizens.

The land designated to the Navajo and Hopi reservation was originally considered barren and unproductive by white settlers until 1921 when prospectors scoured the land for oil. The mining companies pressured the US government to set up Native American councils on the reservations so that they could agree to contracts, specifically leases, in the name of the tribe.[38]

During World War 2, uranium was mined from their land as well though the companies and government neglected to inform the people of the dangers of radiation exposure. Some people had even built their houses out of mine waste. The companies also failed to properly dispose of the radioactive waste which did and will continue to pollute the environment, including the natives’ water sources. Many years later, these same men who worked the mines died from lung cancer and their families received no form of financial compensation.

In 1979, the Church Rock uranium mill spill was the largest release of radioactive waste in US history. The spill contaminated the Puerco River with 1,000 tons of solid radioactive waste and 93 million gallons of acidic, radioactive tailings solution which flowed downstream into the Navajo Nation. The Navajos used the water from this river for irrigation and their livestock but were not immediately informed about the contamination and its danger.[39]

After the war ended, the American population boomed and energy demands soared. The utility companies needed a new source of power so they began the construction of coal-fired power plants. They placed these power plants in the four corners region. In the 1960s, John Boyden, an attorney working for both Peabody Coal and the Hopi tribe, the nation’s largest coal producer, managed to gain rights to the Hopi land, including Black Mesa, a sacred location to both tribes which lay partially within the Joint Use Area of both tribes.

This case is an example of environmental racism and injustice, per the principles established by the Participants of the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit,[40] because the Navajo and Hopi people, which are communities of color low income and political alienation, were disproportionately affected by the proximity and resulting pollution of these power plants which disregard their right to clean air, their land was degraded, and because the related public policies are not based on mutual respect of all people.

The mining companies wanted more land but the joint ownership of the land made negotiations difficult. At the same time, Hopi and Navajo tribes were squabbling over land rights while Navajo livestock continuously grazed on Hopi land. Boyden took advantage of this situation, presenting it to the House Subcommittee on Indian Affairs claiming that if the government did not step in and do something, a bloody war would ensue between the tribes. Congressmen agreed to pass the Navajo-Hopi Land Settlement Act of 1974 which forced any Hopi and Navajo people living on the other’s land to relocate. This affected 6,000 Navajo people and ultimately benefitted coal companies the most who could now more easily access the disputed land. Instead of using military violence to deal with those who refused to move, the government passed what became known as the Bennett Freeze to encourage the people to leave. Under the Bennett Freeze, 1.5 million acres of Navajo land were banned from any type of development, including paving roadways and even fixing roofs. This was meant to only be a temporary incentive to push tribe negotiations but wound up lasting over 40 years until 2009 when President Obama lifted the moratorium.[41] Still, The legacy of the Bennett Freeze still looms over the region as seen by the nearly 3rd world conditions on the reservation - 75% of people do not have access to electricity and housing situations are poor.

The Standing Rock Sioux tribe and the Dakota Access Pipeline

.jpg)

The construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, a 1,172-mile pipeline that delivers crude oil from North Dakota to Iowa, has been in contest with the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, who claim that construction and usage of the pipeline threatens native lands, sacred burial grounds, water supplies provided by Lake Oahe,[42] and environmental health.[43] The pipeline was originally proposed to be built through the northern area of Bismarck, but was rerouted to an area near the Standing Rock Sioux reservation with push back from members of the Bismarck community afraid of the damages the pipeline may bring to their water supply.[44] Bismarck has a 92.4% white-alone demographic,[45] and opponents of the pipeline have been cited in saying that the rerouting of the oil pipeline to the area that may impact indigenous land is racist.[46]

Beginning in April 2016, native and non-native protesters gather on land near Dakota Access Pipeline construction sites to protest the pipeline. Conflict between the tribe members and the government have been occurring since the signing of the Fort Laramie Treaty in 1868, which created the Great Sioux nation and followed with later contention regarding ownership of The Black Hills. In December 2016, the pipeline was temporarily halted and denied easement under President Obama,[47] but President Trump signed an executive order on January 24, 2017;[48] which allowed for continuation of construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Currently, after the forced evacuation of Oceti Sakowin,[49] the Standing Rock Sioux are continuing to contest the construction and continued usage of the pipeline within the United States court system.[50]

Life and culture

Many Native Americans who live on reservations deal with the federal government through two agencies: the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service.

The standard of living on some reservations is comparable to that in the developing world, with issues of infant mortality,[51] life expectancy, poor nutrition, poverty, and alcohol and drug abuse. The two poorest counties in the United States are Buffalo County, South Dakota, home of the Lower Brule Indian Reservation, and Oglala Lakota County, South Dakota, home of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, according to data compiled by the 2000 census.[52]

It is a common conception that environmentalism and a connectedness to nature is ingrained in the Native American culture. In recent years, cultural historians have set out to reconstruct this notion as what they claim to be a culturally inaccurate romanticism.[53] Others recognize the differences between the attitudes and perspectives that emerge from a comparison of Western European philosophy and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) of Indigenous peoples, especially when considering natural resource conflicts and management strategies involving multiple parties.[54]

Gambling

In 1979, the Seminole tribe in Florida opened a high-stakes bingo operation on its reservation in Florida. The state attempted to close the operation down but was stopped in the courts. In the 1980s, the case of California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians established the right of reservations to operate other forms of gambling operations. In 1988, Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, which recognized the right of Native American tribes to establish gambling and gaming facilities on their reservations as long as the states in which they are located have some form of legalized gambling.

Today, many Native American casinos are used as tourist attractions, including as the basis for hotel and conference facilities, to draw visitors and revenue to reservations. Successful gaming operations on some reservations have greatly increased the economic wealth of some tribes, enabling their investment to improve infrastructure, education and health for their people.

Law enforcement and crime

Serious crime on Indian reservations has historically been required (by the 1885 Major Crimes Act, 18 U.S.C. §§1153, 3242, and court decisions) to be investigated by the federal government, usually the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and prosecuted by United States Attorneys of the United States federal judicial district in which the reservation lies.[55]

Tribal courts were limited to sentences of one year or less,[56] until on July 29, 2010, the Tribal Law and Order Act was enacted which in some measure reforms the system permitting tribal courts to impose sentences of up to three years provided proceedings are recorded and additional rights are extended to defendants.[57][58] The Justice Department on January 11, 2010, initiated the Indian Country Law Enforcement Initiative which recognizes problems with law enforcement on Indian reservations and assigns top priority to solving existing problems.

The Department of Justice recognizes the unique legal relationship that the United States has with federally recognized tribes. As one aspect of this relationship, in much of Indian Country, the Justice Department alone has the authority to seek a conviction that carries an appropriate potential sentence when a serious crime has been committed. Our role as the primary prosecutor of serious crimes makes our responsibility to citizens in Indian Country unique and mandatory. Accordingly, public safety in tribal communities is a top priority for the Department of Justice.

Emphasis was placed on improving prosecution of crimes involving domestic violence and sexual assault.[59]

Passed in 1953, Public Law 280 (PL 280) gave jurisdiction over criminal offenses involving Indians in Indian Country to certain States and allowed other States to assume jurisdiction. Subsequent legislation allowed States to retrocede jurisdiction, which has occurred in some areas. Some PL 280 reservations have experienced jurisdictional confusion, tribal discontent, and litigation, compounded by the lack of data on crime rates and law enforcement response.[60]

As of 2012, a high incidence of rape continued to impact Native American women.[61]

Violence and substance abuse

A survey of death certificates over a four-year period showed that deaths among Indians due to alcohol are about four times as common as in the general US population and are often due to traffic collisions and liver disease with homicide, suicide, and falls also contributing. Deaths due to alcohol among American Indians are more common in men and among Northern Plains Indians. Alaska Natives showed the least incidence of death.[62] Under federal law, alcohol sales are prohibited on Indian reservations unless the tribal councils choose to allow it.[63]

Gang violence is becoming a major social problem.[64] A December 13, 2009, The New York Times article about growing gang violence on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation estimated that there were 39 gangs with 5,000 members on that reservation alone.[65]

Martin Luther King Jr's First Visit to an Indian Reservation

On Sept. 20, 1959, Martin Luther King Jr. flew to Tucson, Arizona from Los Angeles to give a talk at the Sunday Evening Forum. On that night, he gave a speech called "A Great Time To Be Alive," at the University of Arizona auditorium, now called Centennial Hall. Following the forum, a reception was held for King, in which he was introduced to Rev. Casper Glenn, the pastor of a multiracial church called the Southside Presbyterian Church. King was very interested in this racially-mixed church and made arrangements to visit it the next day.

The following morning, Glenn picked up King, in his Plymouth station wagon, and drove him to the Southside Presbyterian Church. There, Glenn showed King photographs he had taken of the racially diverse congregation, most of whom were Papago (Tohono O'odham) Indians at the time. Glenn remembers that upon seeing the photos, "King said he had never been on an Indian reservation, nor had he ever had a chance to get to know any Indians." He then requested to be driven to the nearby reservation, as a spur of the moment desire.

The two men traveled on Ajo Way to Sells, Arizona on what was then called the Papago Indian Reservation, now the Tohono O'odham Indian Reservation. When they arrived at the tribal council office, the tribal leaders were surprised to see King and very honored he had come to visit them. King was very anxious to talk to them but was very careful with his questions, as he didn't want to show his lack of knowledge of their tribal heritage. "He was fascinated by everything that they shared with him." Glenn said

The ministers then went to the local Presbyterian church in Sells, which had been recently constructed by its members, with funds provided by the national Presbyterian church. King had a chance to speak to Pastor Towsand who was excited to meet King.

On the way back to Tucson, "King expressed his appreciation of having the opportunity to meet the Indians," Glenn recalled. King left town that day, around 4pm, from the airport.[66]

See also

- Hawaiian home land

- Indian Claims Commission

- Indian colony

- Indian country

- List of historical Indian reservations in the United States

- List of Indian reservations in the United States

- Native American reservation politics

- Reservation poverty

- Reservations in Nebraska

International:

- Ranchería

- Rancherie (term used in British Columbia)

- Indigenous Protected Area in Australia

- Native Community Lands in Bolivia

- Indigenous territory (Brazil)

- Indian reserve in Canada

- Indigenous territory (Colombia)

- Indigenous territories of Costa Rica

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Frequently Asked Questions, Bureau of Indian Affairs". Department of the Interior. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ↑ "AFF Table - Navajo Population" (PDF). Arizona Commission of Indian Affairs. Retrieved 13 Nov 2014.

- ↑ Federal Register, Volume 80, Number 9 dated January 14, 2015

- ↑ Federal Acknowledgment of the Pamunkey Indian Tribe

- ↑ Sutton, 199.

- ↑ Kinney, 1937; Sutton,1975

- ↑ Davies & Clow; Sutton 1991.

- ↑ For general data, see Tiller (1996).

- ↑ See, e.g., United States v. Dion, 476 U.S. 734 (1986); Francis v. Francis, 203 U.S. 233 (1906).

- ↑ "Racial and Ethnic Residential Segregation in the United States: 1980-2000". Census.gov. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ↑ For Los Angeles, see Allen, J. P. and E. Turner, 2002. Text and map of the metropolitan area show the widespread urban distribution of California and other Native Americans.

- ↑ "US should return stolen land to Indian tribes, says United Nations". The Guardian. May 4, 2012.

- ↑ "Native American reservation background". Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Remarks on the Plan for Regulating the Indian Trade, September 1766-October 1766, Founders Online

- ↑ Belko, William S. (2004). "John C. Calhoun and the Creation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs: an Essay on Political Rivalry, Ideology, and Policymaking in the Early Republic". South Carolina Historical Magazine. 105 (3): 170–197. JSTOR 27570693.

- ↑ Bennett, Elmer (2008). Federal Indian Law. The Lawbook Exchange. pp. 201–203. ISBN 9781584777762.

- ↑ "President Grant advances "Peace Policy" with tribes". US National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 15 Nov 2014.

- ↑ Miller Center, University of Virginia, Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ↑ Kinney 1937

- 1 2 Tiller (1996)

- ↑ Getches et al, pp. 140–190.

- ↑ The Equalization Act, 1959.

- ↑ Sutton, ed., 1991.

- ↑ Wishart and Froehling

- ↑ Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, 1988

- ↑ "Enabling Act of 1910" (PDF). Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "'It doesn't seem very fair, because we were here first': resolving the Siou...: Start Your Search!". eds.a.ebscohost.com. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- 1 2 3 "Black Hills Land Claim". Wikipedia. 2017-03-17.

- ↑ "United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians". Wikipedia. 2017-03-12.

- 1 2 3 4 "Saying no to $1 billion: why the impoverished Sioux nation won't take feder...: Start Your Search!". eds.a.ebscohost.com. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ↑ "Why the Sioux Are Refusing $1.3 Billion". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved 2017-03-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Treaty and Land Transaction of 1784, National Park Service

- 1 2 "Hopi Reservation". Wikipedia. 2016-08-14.

- 1 2 "Navajo Nation". Wikipedia. 2017-04-03.

- ↑ Dongoske, Kurt E. (1996-01-01). "The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act: A New Beginning, Not the End, for Osteological Analysis--A Hopi Perspective". American Indian Quarterly. 20 (2): 287–296. doi:10.2307/1185706.

- ↑ DeAngelis, T. (2004). The Navajo: Weavers of the Southwest. Mankato, MN: Blue Earth Books.

- ↑ Reidhead, S. (2001). Wild West.

- ↑ Mudd, V. (Director). (1985). Broken Rainbow [DVD]. United States: Earthworks Films.

- ↑ Pasternak, J. (2010). Yellow dirt: An American story of a poisoned land and a people betrayed. New York, NY: Free Press.

- ↑ Mohai, Paul; Pellow, David; Roberts, J. Timmons (2009-10-15). "Environmental Justice". http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-082508-094348. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-082508-094348. Retrieved 2017-04-19. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Congress.gov | Library of Congress". congress.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- ↑ "FAQ: Standing Rock Litigation". Earthjustice. 2017-02-14. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ↑ "Supporters". Stand With Standing Rock. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- ↑ Service, Amy Dalrymple Forum News. "Pipeline route plan first called for crossing north of Bismarck". Bismarck Tribune. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

- ↑ "Population estimates, July 1, 2015, (V2015)". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

- ↑ "The Dakota Access Pipeline And Environmental Racism". WBEZ. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

- ↑ Savransky, Rebecca (2016-12-04). "Feds deny permit for Dakota Access pipeline". TheHill. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ↑ "Presidential Memorandum Regarding Construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline". whitehouse.gov. 2017-01-24. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ↑ CNN, Mayra Cuevas, Sara Sidner and Darran Simon. "Dakota Access Pipeline protest site is cleared". CNN. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ↑ News, A. B. C. (2017-02-14). "Standing Rock Sioux Ask Court to Halt DAPL Work". ABC News. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ↑ "FastStats". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ↑ Johansen, Bruce E., and Barry Pritzker. 2008. Encyclopedia of American Indian history. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. p. 156. ISBN 9781851098170.

- ↑ Lee., Schweninger, (2008-01-01). Listening to the land : Native American literary responses to the landscape. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820330587. OCLC 812757112.

- ↑ Goode, Ron W. "Tribal-Traditional Ecological Knowledge." News from Native California, vol. 28, no. 3, Spring2015, p. 23. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f5h&AN=102474325&site=eds-live.

- ↑ "Native Americans in South Dakota: An Erosion of Confidence in the Justice System". Usccr.gov. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ↑ "Lawless Lands" Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine., a four-part series in The Denver Post last updated November 21, 2007

- ↑ "Expansion of tribal courts' authority passes Senate" Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine. article by Michael Riley in The Denver Post Posted: 25 June 2010 01:00:00 AM MDT Updated: 25 June 2010 02:13:47 AM MDT Accessed June 25, 2010

- ↑ "President Obama signs tribal-justice changes" Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine. article by Michael Riley in The Denver Post, Posted: 30 July 2010 01:00:00 AM MDT, Updated: 30 July 2010 06:00:20 AM MDT, accessed July 30, 2010

- ↑ "MEMORANDUM FOR UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS WITH DISTRICTS CONTAINING INDIAN COUNTRY" Memorandum by David W. Ogden Deputy Attorney General, Monday, January 11, 2010, Accessed August 12, 2010

- ↑ "Public Law 280 and Law Enforcement in Indian Country – Research Priorities December 2005", accessed August 12, 2010

- ↑ Timonthy Williams (May 22, 2012). "For Native American Women, Scourge of Rape, Rare Justice". The New York Times. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Study: 12 percent of Indian deaths due to alcohol" Associated Press article by Mary Clare Jalonick Washington, D.C. (AP) 9-08 News From Indian Country accessed October 7, 2009

- ↑ "Native American reservation lifts alcohol ban". Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ↑ "Gang Violence On The Rise On Indian Reservations". NPR: National Public Radio. August 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Indian Gangs Grow, Bringing Fear and Violence to Reservation". The New York Times. December 13, 2009

- ↑ Leighton, David (April 2, 2017). "Street Smarts: MLK Jr. raised his voice to the rafters in Tucson". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

Further reading

- J. P. Allen and E. Turner, Changing Faces, Changing Places: Mapping Southern Californians (Northridge, CA: The Center for Geographical Studies, California State University, Northridge, 2002).

- George Pierre Castle and Robert L. Bee, eds., State and Reservation: New Perspectives on Federal Indian Policy (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1992)

- Richmond L. Clow and Imre Sutton, eds., Trusteeship in Change: Toward Tribal Autonomy in Resource Management (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2001).

- Wade Davies and Richmond L. Clow, American Indian Sovereignty and Law: An Annotated Bibliography (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2009).

- T. J. Ferguson and E. Richard Hart, A Zuni Atlas (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985)

- David H. Getches, Charles F. Wilkinson, and Robert A. Williams, Cases and Materials on Federal Indian Law, 4th ed. (St. Paul: West Group, 1998).

- Klaus Frantz, "Indian Reservations in the United States", Geography Research Paper 241 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

- James M. Goodman, The Navajo Atlas: Environments, Resources, People, and History of the Diné Bikeyah (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1982).

- J. P. Kinney, A Continent Lost: A Civilization Won: Indian Land Tenure in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1937)

- Francis Paul Prucha, Atlas of American Indian Affairs (Norman: University of Nebraska Press, 1990).

- C. C. Royce, comp., Indian Land Cessions in the United States, 18th Annual Report, 1896–97, pt. 2 (Wash., D. C.: Bureau of American Ethnology; GPO 1899)

- Imre Sutton, "Cartographic Review of Indian Land Tenure and Territoriality: A Schematic Approach", American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 26:2 (2002): 63–113..

- Imre Sutton, Indian Land Tenure: Bibliographical Essays and a Guide to the Literature (NY: Clearwater Publ. 1975).

- Imre Sutton, ed., "The Political Geography of Indian Country", American Indian Culture and Resource Journal, 15()2):1–169 (1991).

- Imre Sutton, "Sovereign States and the Changing Definition of the Indian Reservation", Geographical Review, 66:3 (1976): 281–295.

- Veronica E. Velarde Tiller, ed., Tiller's Guide to Indian Country: Economic Profiles of American Indian Reservations (Albuquerque: BowArrow Pub., 1996/2005)

- David J. Wishart and Oliver Froehling, "Land Ownership, Population and Jurisdiction: the Case of the 'Devils Lake Sioux Tribe v. North Dakota Public Service Commission'," American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 20(2): 33–58 (1996).

- Laura Woodward-Ney, Mapping Identity: The Coeur d'Alene Indian Reservation, 1803–1902 (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2004)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Indian reservations. |

- BIA full-size map of Indian reservations in the continental United States

- BIA index to map of Indian reservations in the continental United States

- US Census tallies for Indian reservations

- Chapter 5: American Indian and Alaska Native Areas, U.S. Census Bureau, Geographic Areas Reference manual (PDF)

- FEMA: Federally recognized Indian reservations

- Tribal Leaders Directory

- Wheeler-Howard Act (Indian Reorganization Act) 1934

- Native American Technical Corrections Act of 2003

- Gambling on the reservation April 2004 Christian Science Monitor article with links to other Monitor articles on the topic

- Henry Red Cloud of Oglala Lakota Tribe on the Recession's Toll on Reservations—video report by Democracy Now!

- TribalJusticeandSafety.gov U.S. Department of Justice website devoted to Indian issues

- "Public Law 280 and Law Enforcement in Indian Country – Research Priorities"

- Indian land cession by years