Narrow-gauge railways in Canada

| By transport mode | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tram · Rapid transit Miniature · Scale model | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| By size (list) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Change of gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Break-of-gauge · Dual gauge · Conversion (list) · Bogie exchange · Variable gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| By location | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| North America · South America · Europe · Australia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Although most railways of central and eastern Canada were initially built to a 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm) broad gauge, there were several, especially in The Maritimes and Ontario, which were built as individual narrow-gauge lines. These were generally less expensive to build, but were more vulnerable to frost heaving because vertical displacement of one rail caused greater angular deflection of the narrower two-rail running surface. Most of the longer examples were regauged starting in the 1880s as the railway network began to be bought up by larger companies.

The largest systems in the country were the 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) lines such as: the Newfoundland Railway and others on the island of Newfoundland (969 mi or 1,559 km); Ontario's Toronto and Nipissing Railway and Toronto, Grey and Bruce Railway (304 mi or 489 km); the Prince Edward Island Railway (280 mi or 450 km); and the New Brunswick Railway (189 mi or 304 km) in the Saint John River valley of New Brunswick. Various mining and industrial operations in Canada have also operated narrow-gauge railways.

By 2015, the only remaining narrow-gauge system in Canada was the White Pass and Yukon Route, which used some of the rolling stock of the Newfoundland Railway which closed in the late 1980s.

Newfoundland

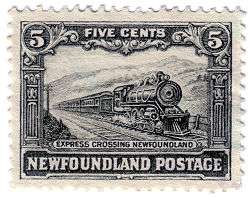

Construction on the 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) Newfoundland Railway began in 1881 and continued on amid recrimination and lawsuits until the line crossed the island to the ferry port at Port aux Basques in 1898. Since no roads existed, it was an economic life-line for the country to the rest of North America, but it chronically lost money. The Newfoundland government took it over in 1923, and the Canadian government transferred it to Canadian National Railways when Newfoundland became part of Canada in 1949.

After the Trans-Canada Highway was completed across Newfoundland in 1965, trucks took most of its freight service in the same year as CN instituted the first railcar ferry service to the island. Standard-gauge cars had their trucks switched to narrow gauge for movement on the island. Interchange with the North American system did not improve the traffic levels and even the CNR started to move its own freight increasingly by truck. The death knell came for both the Newfoundland and P.E.I. Railways in 1987 when Canada deregulated its railway industry and allowed railways to abandon money-losing lines.

The Newfoundland Railway was the longest narrow-gauge system in North America at the time of its abandonment in September 1988. It was also the last commercial common carrier narrow-gauge railway in Canada, since the White Pass & Yukon had closed earlier in the decade.

Prince Edward Island

When the 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) Prince Edward Island Railway was built starting in 1871, the contractors were promised a fixed price per mile but the colonial government failed to specify how many miles were to be built. As a result, the railway wandered all over the landscape. By 1872, construction debts threatened to bankrupt the colony. When Prince Edward Island joined Canada in 1873, it did so under the condition that the Canadian government take over the railway. It did so, and completed the conversion to 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) during the 1920s and early 1930s after the island's rail system was linked to North America by a standard-gauge railcar ferry beginning in 1917. The entire standard-gauge system was abandoned by CN in 1989.

Nova Scotia

The first narrow-gauge railway in Canada was not a common carrier, but the 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) Lingan Colliery Tramway built in 1861 on Cape Breton Island north of Sydney. Cars were pulled by horses until a 0-4-0 saddle tank locomotive arrived in 1866 for the final year of operation.[1] The Glasgow and Cape Breton Coal and Railway Company operated the first Canadian 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge railway from 1871 to 1893 with 41 miles (70 kilometers) of branch lines linking several mines to Sydney.[2]

New Brunswick

The New Brunswick Railway was constructed in the 1870s up the Saint John River valley from South Devon (opposite Fredericton) to Edmundston. It was built to 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) but was standard-gauged several years later. In 1890, the line was absorbed into the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Quebec

The Lake Champlain and St. Lawrence Junction Railway commenced operation in the Richelieu River valley between Stanbridge and Saint-Guillaume in October 1879. The 100-kilometre (62-mile) rail line and locomotives were converted to 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) (standard gauge) in 1881. The line was leased to the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1887 and survived into the 21st century as part of the CPR Farnham Division.[3]

Ontario

In Ontario, the Toronto, Grey and Bruce Railway (TG&BR) and the Toronto and Nipissing Railway (T&NR), were the first public passenger carrying narrow-gauge railways on the continent of North America, coming into service in the summer of 1871. The gauge of 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) was chosen on the recommendation of Carl Abraham Pihl, Chief Engineer of the Norwegian State Railways, who had adopted this gauge in Norway in the early 1860s. Sir Charles Fox, engineer and constructor of the Crystal Palace at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London’s Hyde Park, was largely responsible for adoption of the gauge throughout the former British Empire and Colonies, it becoming commonly known as the ‘Colonial’ gauge. The objective of the Toronto, Grey and Bruce Railway and the Toronto and Nipissing Railway was to open up the bush country north of Toronto to settlement and commerce. The lines were first surveyed by John Edward Boyd of St. John, New Brunswick who, as Railway Engineer of that colony in the 1860s, had advocated the construction of the New Brunswick Railway on the gauge of 3 ft 6 in. Boyd later became the Chief Engineer of the narrow-gauge Prince Edward Island Railway. The chief Engineer of both the Toronto, Grey and Bruce Railway and the Toronto and Nipissing Railway was Edmund Wragge, a former pupil and associate of Sir Charles Fox. Wragge returned to Britain between 1895 and 1905 and was honoured by the award of the Telford Gold Medal of the Institution of Civil Engineers for his work on the approach to and construction of the London (Marylebone) terminus of the Great Central Railway. The Ontario lines were of substantial length, over 300 miles (480 km) in aggregate, and both were built with the objective of connecting with a future Pacific railway, at Lake Nipissing in the case of the T&NR, and via steamers to the Lakehead in the case of the TG&BR. Only the latter was achieved. Although independent of each other financially, they were promoted and engineered by the same men and were in fact connected by a short length of third rail in the Toronto waterfront trackage of the Grand Trunk Railway. These Ontario railways attempted several innovations in addition to the adoption of the narrow gauge: the use of Clark’s six wheel radial axles for longer stock – a complete failure and never used; the use of four wheel boxcars for economy and flexibility – not entirely successful; the use of large Fairlie articulated 0-6-6-0 freight locomotives (see illustration) – found very powerful and useful initially, but heavy on maintenance and not pursued further; and the early use of powerful Avonside Engine Company 4-6-0 and Baldwin Locomotive Works 2-8-0 locomotives for freight haulage – very successful engines which remained in service with the Canadian Pacific Railway after gauge standardization. Initially very successful in stimulating trade, the two railways had difficulty carrying all the traffic offered in the early 1870s. Then, after they had bought large numbers of additional freight locomotives and boxcars, the traffic fell off due to the economic depression of the mid-1870s and was insufficient to support the heavy financial burden of the capital invested. A case of ‘too much, too late’. Like all smaller railways in central Canada in the early 1880s their financial difficulties made them vulnerable in the battle for feeder routes and traffic between the Grand Trunk Railway and the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). The Toronto and Nipissing Railway was amalgamated into the Midland Railway of Canada in 1881 and made standard gauge as part of the Midland's plan to obtain direct access to Toronto; later the whole enterprise was absorbed by the Grand Trunk Railway. The Toronto, Grey and Bruce Railway was first acquired by the Grand Trunk Railway which converted it to standard gauge in 1881, but following its own financial embarrassment it was forced to cede control to the Ontario and Quebec Railway a proxy for the Canadian Pacific Railway. Much of the trackage has been abandoned and lifted but some remains in service. 20 miles (32 km) of the T&NR from Toronto to Stouffville carries GO Transit commuter trains and a further 12 miles (19 km) from Stouffville to Uxbridge, Ontario, is operated as a tourist line by the York Durham Heritage Railway. 26 miles (42 km) of the TG&BR from Toronto to Bolton, Ontario, carries CPR freight trains, and about 3 miles (4.8 km) from Melville Junction to Orangeville is operated by the Orangeville-Brampton Railway. Another tourist line, the Portage Flyer, operates at the Muskoka Heritage Place museum complex in Huntsville, and runs on .75 miles (1.21 km) of 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) narrow-gauge track.[4]

Yukon

There were numerous narrow-gauge lines in the North—these include the Northern Light and Power coal line near Dawson; The Klondike Mines Railway in Dawson City and the Taku Tram. Several of the steam engines survive from these ventures: the Duchess at Taku, a Porter in Dawson and another in Tenana.

The only narrow-gauge system still in operation in the country is the 3 ft (914 mm) gauge White Pass and Yukon Route. The WPYR was built as a common carrier but closed in 1982 only to reopen in 1988 to haul tourists from cruise ships docking at Skagway, Alaska through White Pass on the Canada–United States border to Bennett, British Columbia, and more recently onto Carcross, Yukon. It uses some rolling stock from the now-defunct 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) Newfoundland Railway after changing the trucks.

British Columbia

BC has had a long history with narrow-gauge railways starting with the horse-drawn and gravity-assisted Seton Lake tramway in 1858, and then to the 3 ft (914 mm) gauge coal mine railways at Nanaimo. Coal was moved to the pier at Departure Bay. Other railways sprang up including the Kaslo and Slocan Railway, the Columbia and Western Railway near Trail, and the Leonora and Mt. Sicker Railway on Vancouver Island. Narrow-gauge lines were used extensively in mining and logging. However, by 1910 narrow-gauge logging lines were phased out as it was found that they were unsafe for the large BC timber. Other small industrial lines used narrow gauge for a few years—the Kitsault Mine, and the Western Peat operation in Burns Bog. Narrow gauge worked in the Kootenays too at the coke ovens at Fernie and logging sites of Cranbrook. The White Pass and Yukon Route in the far north west corner of the province, connects Alaska, BC and the Yukon. It is still in operation and seasonally steam hauled. See List of historic BC Narrow Gauge railways.

Alberta

There were several 3 ft (914 mm) mining systems in the Drumheller area. An extensive narrow-gauge line was built in the foothills to haul coal about 1890 but was soon re-gauged to standard and the equipment moved to the Kaslo and Slocan in BC.

The North Western Coal and Navigation Company, constructed an 3 ft (914 mm) narrow-gauge line which began operations from Lethbridge to Dunmore, Alberta beginning in the fall of 1885. In 1893 Canadian Pacific Railway, leased the line and later purchased it in 1897, and then converted it to standard gauge. Additionally the North Western Coal and Navigation Company constructed another 3 ft (914 mm) narrow-gauge line which ran from Lethbridge to Great Falls, Montana, and was opened for use in the fall of 1890.

The line was later converted to standard gauge in 1901, and was soon afterwards sold to two different buyers; Great Northern Railway (U.S.), for the American portion of the line, and Canadian Pacific Railway, for the Canadian portion of the line. That narrow-gauge line included the International Train Station Depot North West Territories that sat half in Coutts and half in Sweetgrass.

This unique structure was used by North Western Coal and Navigation Company, and later on after selling the railroad by Great Northern Railway (U.S.) and Canadian Pacific Railway. In 1915, Canadian Pacific Railway split the Train Station in half and hauled their portion north across the Canada–United States border and continued to use it until the late 1960s when it was closed. At the same time, Great Northern Railway (U.S.) hauled their portion of the station south of the Canada–United States border, and used it until the early 1930s.

Currently the International Train Station Depot is located at the Galt Historic Railway Park, in the County of Warner No. 5, Alberta, and is open to the public.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Lavallee (1972) p.11

- ↑ Lavallee (1972) pp.16-17 & 112

- ↑ Lavallee (1972) pp.27-28 & 92

- ↑ Surviving Steam Locomotives in Ontario

References

- "Narrow Gauge Through the Bush - Ontario's Toronto Grey & Bruce and Toronto & Nipissing Railways"; Rod Clarke; pub. Beaumont and Clarke, with the Credit Valley Railway Company, Streetsville, Ontario, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9784406-0-2

- "The Narrow Gauge For Us - The Story of the Toronto and Nipissing Railway"; Charles Cooper; pub. The Boston Mills Press; Erin, Ontario, 1982. ISBN 0-919822-72-X

- "Narrow Gauge Railways of Canada"; Omer Lavallee; pub. Railfair, Montreal, 1972. ISBN 0-919130-21-6

- "Narrow Gauge Railways of Canada"; Omer Lavallee, expanded and revised by Ronald S Ritchie; pub. Fitzhenry and Whiteside, Markham, Ontario, 2005. ISBN 1-55041-830-0

- "The Toronto Grey and Bruce Railway 1863-1884; Thomas F McIlwraith; pub. Upper Canada Railway Society, Toronto, 1963.

- "Steam Trains to the Bruce"; Ralph Beaumont; pub. The Boston Mills Press; Cheltenham, Ontario, 1977. ISBN 0-919822-21-5

- "Running Late on the Bruce"; Ralph Beaumont & James Filby; pub The Boston Mills Press, Cheltenham, Ontario, 1980. ISBN 0-919822-32-0

External links

- 'The Narrow Gauge for Us' Charles Cooper's Railway Pages

- 'Narrow Gauge Through the Bush' Charles Cooper's Railway Pages

- 'Toronto Grey and Bruce' R L Kennedy's Old Time Trains

- 'Narrow Gauge Through the Bush' R Milland Pages