Dominican Republic

Coordinates: 19°00′N 70°40′W / 19.000°N 70.667°W

| Dominican Republic | |

|---|---|

|

Motto: "Dios, Patria, Libertad" (Spanish) "God, Homeland, Freedom" | |

.svg.png) | |

| Capital and largest city |

Santo Domingo 19°00′N 70°40′W / 19.000°N 70.667°W |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Ethnic groups (1960[1]a) | |

| Demonym | Dominican |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Danilo Medina | |

| Margarita Cedeño de Fernández | |

| Legislature | Congress |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| Independence | |

| December 1, 1821[2] | |

| February 27, 1844[2] (not recognized by Haiti until November 9, 1874)c[3] | |

| August 16, 1863[2] (recognized on March 3, 1865) | |

• from the United States (occupation) | July 12, 1924[4] |

| Area | |

• Total | 48,442 km2 (18,704 sq mi) (128th) |

• Water (%) | 0.7[5] |

| Population | |

• 2016 estimate | 10,075,045[6] (88th) |

| 9,478,612[7] | |

• Density | 197/km2 (510.2/sq mi) (65th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $174.180 billion[8] (72nd) |

• Per capita | $17,096[8] (76th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $76.850 billion[8] (67th) |

• Per capita | $7,543[8] (74th) |

| Gini (2012) |

high |

| HDI (2015) |

high · 99th |

| Currency | Peso[2] (DOP) |

| Time zone | Standard Time Caribbean (UTC −4:00[5]) |

| Drives on the | right |

| Calling code | +1-809, +1-829, +1-849 |

| ISO 3166 code | DO |

| Internet TLD | .do[5] |

| |

The Dominican Republic (Spanish: República Dominicana [reˈpuβlika ðominiˈkana]) is a sovereign state occupying the eastern five-eighths of the island of Hispaniola, in the Greater Antilles archipelago in the Caribbean region. The western three-eighths of the island is occupied by the nation of Haiti,[11][12] making Hispaniola one of two Caribbean islands, along with Saint Martin, that are shared by two countries. The Dominican Republic is the second-largest Caribbean nation by area (after Cuba) at 48,445 square kilometers (18,705 sq mi), and third by population with approximately 10 million people, of which approximately three million live in the metropolitan area of Santo Domingo, the capital city.[13][14]

Christopher Columbus landed on the Western part of Hispaniola, in what is now Haiti, on December 6, 1492. The island became the first seat of Spanish colonial rule in the New World. The Dominican people declared independence in November 1821 but were forcefully annexed by their more powerful neighbor Haiti in February 1822. After the 1844 victory in the Dominican War of Independence against Haitian rule the country fell again under Spanish colonial rule until the Dominican War of Restoration of 1865.[15][16][17]

The Dominican Republic experienced mostly internal strife (Second Republic) until 1916. A United States occupation lasted eight years between 1916 and 1924, and a subsequent calm and prosperous six-year period under Horacio Vásquez Lajara was followed by the dictatorship of Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina until 1961. A civil war in 1965, the country's most recent, was ended by another U.S. military occupation and was followed by the authoritarian rule of Joaquín Balaguer from 1966 to 1978. Since then, the Dominican Republic has moved toward representative democracy[5] and has been led by Leonel Fernández for most of the time since 1996. Danilo Medina, the Dominican Republic's current president, succeeded Fernandez in 2012, winning 51% of the electoral vote over his opponent, ex-president Hipólito Mejía.[18]

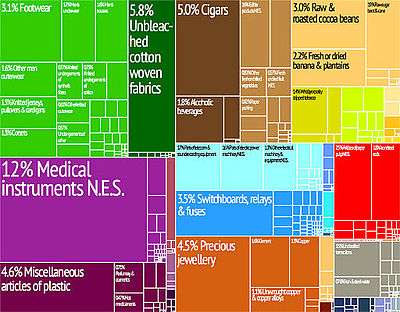

The Dominican Republic has the ninth-largest economy in Latin America and is the largest economy in the Caribbean and Central American region.[19][20] Though long known for agriculture and mining, the economy is now dominated by services.[5] Over the last two decades, the Dominican Republic have been standing out as one of the fastest-growing economies in the Americas – with an average real GDP growth rate of 5.4% between 1992 and 2014.[21] GDP growth in 2014 and 2015 reached 7.3 and 7.0%, respectively, the highest in the Western Hemisphere.[21] In the first half of 2016 the Dominican economy grew 7.4% continuing its trend of rapid economic growth.[22]

Recent growth has been driven by construction, manufacturing and tourism. Private consumption has been strong, as a result of low inflation (under 1% on average in 2015), job creation, as well as high level of remittances. The Dominican Republic has a stock market, Bolsa de Valores de la Republica Dominicana (BVRD).[23] and advanced telecommunication system and transportation infrastructure.[24] Nevertheless, unemployment,[5] government corruption, and inconsistent electric service remain major problems. The country also has "marked income inequality."[5] International migration affects the Dominican Republic greatly, as it receives and sends large flows of migrants. Mass illegal Haitian immigration and the integration of Dominicans of Haitian descent are major issues.[25] A large Dominican diaspora exists, mostly in the United States,[26] contributes to development, sending billions of dollars to Dominican families in remittances.[5][27]

The Dominican Republic is the most visited destination in the Caribbean. The year-round golf courses are major attractions.[24] A geographically diverse nation, the Dominican Republic is home to both the Caribbean's tallest mountain peak, Pico Duarte, and the Caribbean's largest lake and point of lowest elevation, Lake Enriquillo.[28] The island has an average temperature of 26 °C (78.8 °F) and great climatic and biological diversity.[24] The country is also the site of the first cathedral, castle, monastery, and fortress built in the Americas, located in Santo Domingo's Colonial Zone, a World Heritage Site.[29][30] Music and sport are of great importance in the Dominican culture, with Merengue and Bachata as the national dance and music, and baseball as the favorite sport.[2]

Names and etymology

For most of its history, up until independence, the country was known as Santo Domingo[31] — the name of its present capital and patron saint, Saint Dominic—and continued to be commonly known as such in English until the early 20th century.[32] The residents were called Dominicanos (Dominicans), which is the adjective form of "Domingo", and the revolutionaries named their newly independent country La República Dominicana.

In the national anthem of the Dominican Republic (Himno Nacional) the term "Dominican" does not appear. The author of its lyrics, Emilio Prud'Homme, consistently uses the poetic term Quisqueyanos, that is, "Quisqueyans". The word "Quisqueya" derives from a native tongue of the Taino Indians and means "Mother of all Lands". It is often used in songs as another name for the country. The name of the country is often shortened to "the D.R."[33]

History

Pre-European history

The Arawakan-speaking Taíno moved into Hispaniola from the north east region of what is now known as South America, displacing earlier inhabitants,[34] c. AD 650. They engaged in farming and fishing[35] and hunting and gathering.[34] The fierce Caribs drove the Taíno to the northeastern Caribbean during much of the 15th century.[36] The estimates of Hispaniola's population in 1492 vary widely, including one hundred thousand,[37] three hundred thousand,[34] and four hundred thousand to two million.[38] Determining precisely how many people lived on the island in pre-Columbian times is next to impossible, as no accurate records exist.[39] By 1492 the island was divided into five Taíno chiefdoms.[40][41] The Taíno name for the entire island was either Ayiti or Quisqueya.[42]

The Spaniards arrived in 1492. After initially friendly relationships, the Taínos resisted the conquest, led by the female Chief Anacaona of Xaragua and her ex-husband Chief Caonabo of Maguana, as well as Chiefs Guacanagaríx, Guamá, Hatuey, and Enriquillo. The latter's successes gained his people an autonomous enclave for a time on the island. Within a few years after 1492 the population of Taínos had declined drastically, due to smallpox,[43] measles, and other diseases that arrived with the Europeans,[44] and from other causes discussed below.

The first recorded smallpox outbreak in the Americas occurred on Hispaniola in 1507.[44] The last record of pure Taínos in the country was from 1864. Still, Taíno biological heritage survived to an important extent, due to intermixing. Census records from 1514 reveal that 40% of Spanish men in Santo Domingo were married to Taino women,[45] and some present-day Dominicans have Taíno ancestry.[46][47] Remnants of the Taino culture include their cave paintings,[48] as well as pottery designs which are still used in the small artisan village of Higüerito, Moca.[49]

European colonization

Christopher Columbus arrived on Hispaniola on December 5, 1492, during the first of his four voyages to America. He claimed the land for Spain and named it La Española, because the diverse climate and terrain reminded him of the country.[50] In 1496 Bartholomew Columbus, Christopher's brother, built the city of Santo Domingo, Western Europe's first permanent settlement in the "New World." The Spaniards created a plantation economy on the island.[37] The colony was the springboard for the further Spanish conquest of America and for decades the headquarters of Spanish power in the hemisphere.

The Taínos nearly disappeared, above all, from European infectious diseases to which they had no immunity.[51] Other causes were abuse, suicide, the breakup of family, starvation,[34] the encomienda system,[52] which resembled a feudal system in Medieval Europe,[53] war with the Spaniards, changes in lifestyle, and mixing with other peoples. Laws passed for the Indians' protection (beginning with the Laws of Burgos, 1512–1513)[54] were never truly enforced.

Some scholars believe that las Casas exaggerated[55] the Indian population decline in an effort to persuade King Carlos to intervene and that encomenderos also exaggerated it, in order to receive permission to import more African slaves. Moreover, censuses of the time omitted the Indians who fled into remote communities,[46] where they often joined with runaway Africans (cimarrones), producing Zambos. Also, Mestizos who were culturally Spanish were counted as Spaniards, some Zambos as black, and some Indians as Mulattoes.

After its conquest of the Aztecs and Incas, Spain neglected its Caribbean holdings. English and French buccaneers settled in northwestern Hispaniola coast and, after years of struggles with the French, Spain ceded the western coast of the island to France with the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, whilst the Central Plateau remained under Spanish domain. France created a wealthy colony Saint-Domingue there, while the Spanish colony suffered an economic decline.[56]

The colony of Santo Domingo saw a spectacular population increase during the 17th century, as it rose from some 6,000 in 1637 to about 91,272 in 1750. Of this number approximately 38,272 were white landowners, 38,000 were free mixed people of color, and some 15,000 were slaves. This contrasted sharply with the population of the French colony of Saint-Domingue (present day Haiti) – which had a population that was 90% enslaved and overall seven times as numerous as the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo.[56]

French rule (1795–1809)

France came to own Hispaniola in 1795 when by the Peace of Basel Spain ceded Santo Domingo as a consequence of the French Revolutionary Wars. The recently freed Africans led by Toussaint Louverture in 1801, took over Santo Domingo in the east, thus gaining control of the entire island. In 1802 an army sent by Napoleon captured Toussaint Louverture and sent him to France as prisoner. Toussaint Louverture’s lieutenants and the spread of yellow fever succeeded in driving the French again from Saint-Domingue, which in 1804 the rebels made independent as the Republic of Haiti. Eastwards, France continued to rule Spanish Santo Domingo.

In 1805, Haitian troops of general Henri Christophe invaded Santo Domingo and sacked the towns of Santiago de los Caballeros and Moca, killing most of their residents and helping to lay the foundation for two centuries of animosity between the two countries.

In 1808, following Napoleon's invasion of Spain, the criollos of Santo Domingo revolted against French rule and, with the aid of the United Kingdom (Spain's ally) returned Santo Domingo to Spanish control.[57]

Reversion to Spain (1809–1821)

See España Boba.

Independence from Spain (1821)

After a dozen years of discontent and failed independence plots by various opposing groups, Santo Domingo's former Lieutenant-Governor (top administrator), José Núñez de Cáceres, declared the colony's independence from the Spanish crown as Spanish Haiti, on November 30, 1821. This period is also known as the Ephemeral independence.[58]

Unification of Hispaniola (1822–44)

_Portrait.jpg)

The newly independent republic ended two months later under the Haitian government led by Jean-Pierre Boyer.[59]

As Toussaint Louverture had done two decades earlier, the Haitians abolished slavery. In order to raise funds for the huge indemnity of 150 million francs that Haiti agreed to pay the former French colonists, and which was subsequently lowered to 60 million francs, the Haitian government imposed heavy taxes on the Dominicans. Since Haiti was unable to adequately provision its army, the occupying forces largely survived by commandeering or confiscating food and supplies at gunpoint. Attempts to redistribute land conflicted with the system of communal land tenure (terrenos comuneros), which had arisen with the ranching economy, and some people resented being forced to grow cash crops under Boyer and Joseph Balthazar Inginac's Code Rural.[60] In the rural and rugged mountainous areas, the Haitian administration was usually too inefficient to enforce its own laws. It was in the city of Santo Domingo that the effects of the occupation were most acutely felt, and it was there that the movement for independence originated.

Haiti's constitution forbade white elites from owning land, and Dominican major landowning families were forcibly deprived of their properties. Many emigrated to Cuba, Puerto Rico (these two being Spanish possessions at the time), or Gran Colombia, usually with the encouragement of Haitian officials who acquired their lands. The Haitians associated the Roman Catholic Church with the French slave-masters who had exploited them before independence and confiscated all church property, deported all foreign clergy, and severed the ties of the remaining clergy to the Vatican.

All levels of education collapsed; the university was shut down, as it was starved both of resources and students, with young Dominican men from 16 to 25 years old being drafted into the Haitian army. Boyer's occupation troops, who were largely Dominicans, were unpaid and had to "forage and sack" from Dominican civilians. Haiti imposed a "heavy tribute" on the Dominican people.[61]:page number needed

Many whites fled Santo Domingo for Puerto Rico and Cuba (both still under Spanish rule), Venezuela, and elsewhere. In the end the economy faltered and taxation became more onerous. Rebellions occurred even by Dominican freedmen, while Dominicans and Haitians worked together to oust Boyer from power. Anti-Haitian movements of several kinds – pro-independence, pro-Spanish, pro-French, pro-British, pro-United States – gathered force following the overthrow of Boyer in 1843.[61]:page number needed

Independence from Haiti (1844)

In 1838 Juan Pablo Duarte founded a secret society called La Trinitaria, which sought the complete independence of Santo Domingo without any foreign intervention.[62]:p147–149 Matías Ramón Mella and Francisco del Rosario Sánchez, despite not being among the founding members of La Trinitaria, were decisive in the fight for independence. Duarte, Mella, and Sánchez are considered the three Founding Fathers of the Dominican Republic.[63]

On February 27, 1844, the Trinitarios (the members of La Trinitaria), declared the independence from Haiti. They were backed by Pedro Santana, a wealthy cattle rancher from El Seibo, who became general of the army of the nascent republic. The Dominican Republic's first Constitution was adopted on November 6, 1844, and was modeled after the United States Constitution.[35]

The decades that followed were filled with tyranny, factionalism, economic difficulties, rapid changes of government, and exile for political opponents. Threatening the nation's independence were renewed Haitian invasions occurring in 1844, 1845–49, 1849–55, and 1855–56.[61]:page number needed Haiti did not recognize the Dominican Republic until 1874.[3][64]

Meanwhile, archrivals Santana and Buenaventura Báez held power most of the time, both ruling arbitrarily. They promoted competing plans to annex the new nation to another power: Santana favored Spain, and Báez the United States.

Restoration republic

In 1861, after imprisoning, silencing, exiling, and executing many of his opponents and due to political and economic reasons, Santana signed a pact with the Spanish Crown and reverted the Dominican nation to colonial status, the only Latin American country to do so. His ostensible aim was to protect the nation from another Haitian annexation.[65] Opponents launched the War of Restoration in 1863, led by Santiago Rodríguez, Benito Monción, and Gregorio Luperón, among others. Haiti, fearful of the re-establishment of Spain as colonial power on its border, gave refuge and supplies to the revolutionaries.[65] The United States, then fighting its own Civil War, vigorously protested the Spanish action. After two years of fighting, Spain abandoned the island in 1865.[65]

Political strife again prevailed in the following years; warlords ruled, military revolts were extremely common, and the nation amassed debt. It was now Báez's turn to act on his plan of annexing the country to the United States, where two successive presidents were supportive.[35][59][66] U.S. President Grant desired a naval base at Samaná and also a place for resettling newly freed Blacks.[67] The treaty, which included U.S. payment of $1.5 million for Dominican debt repayment, was defeated in the United States Senate in 1870[59] on a vote of 28–28, two-thirds being required.[68][69][70]

Báez was toppled in 1874, returned, and was toppled for good in 1878. A new generation was thence in charge, with the passing of Santana (he died in 1864) and Báez from the scene. Relative peace came to the country in the 1880s, which saw the coming to power of General Ulises Heureaux.[71]

"Lilís," as the new president was nicknamed, enjoyed a period of popularity. He was, however, "a consummate dissembler," who put the nation deep into debt while using much of the proceeds for his personal use and to maintain his police state. Heureaux became rampantly despotic and unpopular.[71][72] In 1899 he was assassinated. However, the relative calm over which he presided allowed improvement in the Dominican economy. The sugar industry was modernized,[73]:p10 and the country attracted foreign workers and immigrants.

20th century (1900–30)

From 1902 on, short-lived governments were again the norm, with their power usurped by caudillos in parts of the country. Furthermore, the national government was bankrupt and, unable to pay Heureaux's debts, faced the threat of military intervention by France and other European creditor powers.[74]

United States President Theodore Roosevelt sought to prevent European intervention, largely to protect the routes to the future Panama Canal, as the canal was already under construction. He made a small military intervention to ward off European powers, to proclaim his famous Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, and also to obtain his 1905 Dominican agreement for U.S. administration of Dominican customs, which was the chief source of income for the Dominican government. A 1906 agreement provided for the arrangement to last 50 years. The United States agreed to use part of the customs proceeds to reduce the immense foreign debt of the Dominican Republic and assumed responsibility for the Dominican debt.[35][74]

After six years in power, President Ramón Cáceres (who had himself assassinated Heureaux)[71] was assassinated in 1911. The result was several years of great political instability and civil war. U.S. mediation by the William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson administrations achieved only a short respite each time. A political deadlock in 1914 was broken after an ultimatum by Wilson telling the Dominicans to choose a president or see the U.S. impose one. A provisional president was chosen, and later the same year relatively free elections put former president (1899–1902) Juan Isidro Jimenes Pereyra back in power. To achieve a more broadly supported government, Jimenes named opposition individuals to his cabinet. But this brought no peace and, with his former Secretary of War Desiderio Arias maneuvering to depose him and despite a U.S. offer of military aid against Arias, Jimenes resigned on May 7, 1916.[75]

In response, Wilson ordered the U.S. occupation of the Dominican Republic. U.S. Marines landed on May 16, 1916, and had control of the country two months later. The military government established by the U.S., led by Vice Admiral Harry Shepard Knapp, was widely repudiated by the Dominicans, with many factions within the country leading guerrilla campaigns against U.S. forces.[75] The occupation regime kept most Dominican laws and institutions and largely pacified the general population. The occupying government also revived the Dominican economy, reduced the nation's debt, built a road network that at last interconnected all regions of the country, and created a professional National Guard to replace the warring partisan units.[75]

Vigorous opposition to the occupation continued, nevertheless, and after World War I it increased in the U.S. as well. There, President Warren G. Harding (1921–23), Wilson's successor, worked to put an end to the occupation, as he had promised to do during his campaign. The U.S. government's rule ended in October 1922, and elections were held in March 1924.[75]

The victor was former president (1902–03) Horacio Vásquez Lajara, who had cooperated with the U.S. He was inaugurated on July 13, and the last U.S. forces left in September. Vásquez gave the country six years of stable governance, in which political and civil rights were respected and the economy grew strongly, in a relatively peaceful atmosphere.[75][76]

During the government of Horacio Vásquez, Rafael Trujillo held the rank of lieutenant colonel and was chief of police. This position helped him launch his plans to overthrow the government of Vásquez. Trujillo had the support of Carlos Rosario Peña, who formed the Civic Movement, which had as its main objective to overthrow the government of Vásquez.

In February 1930, when Vásquez attempted to win another term, his opponents rebelled in secret alliance with the commander of the National Army (the former National Guard), General Rafael Leonidas Trujillo Molina. Trujillo secretly cut a deal with rebel leader Rafael Estrella Ureña; in return for letting Ureña take power, Trujillo would be allowed to run for president in new elections. As the rebels marched toward Santo Domingo, Vásquez ordered Trujillo to suppress them. However, feigning "neutrality," Trujillo kept his men in barracks, allowing Ureña's rebels to take the capital virtually uncontested. On March 3, Ureña was proclaimed acting president with Trujillo confirmed as head of the police and the army.

As per their agreement, Trujillo became the presidential nominee of the newly formed Patriotic Coalition of Citizens (Spanish: Coalición patriotica de los ciudadanos), with Ureña as his running mate. During the election campaign, Trujillo used the army to unleash a campaign of political repression that forced his opponents to withdraw from the race. In May Trujillo was elected president virtually unopposed after a violent campaign against his opponents, ascending to power in August 16, 1930.

Trujillo Age (1930–61)

There was considerable economic growth during Rafael Trujillo's long and iron-fisted regime, although a great deal of the wealth was taken by the dictator and other regime elements. There was progress in healthcare, education, and transportation, with the building of hospitals and clinics, schools, and roads and harbors. Trujillo also carried out an important housing construction program and instituted a pension plan. He finally negotiated an undisputed border with Haiti in 1935 and achieved the end of the 50-year customs agreement in 1941, instead of 1956. He made the country debt-free in 1947.[35]

This was accompanied by absolute repression and the copious use of murder, torture, and terrorist methods against the opposition. Trujillo renamed Santo Domingo to "Ciudad Trujillo" (Trujillo City),[35] the nation's – and the Caribbean's – highest mountain La Pelona Grande (Spanish for: The Great Bald) to "Pico Trujillo" (Spanish for: Trujillo Peak), and many towns and a province. Some other places he renamed after members of his family. By the end of his first term in 1934 he was the country's wealthiest person,[62]:p360 and one of the wealthiest in the world by the early 1950s;[77] near the end of his regime his fortune was an estimated $800 million.[73]:p111

Although one-quarter Haitian, Trujillo promoted propaganda against them.[78] In 1937, he ordered what became known as the Parsley Massacre or, in the Dominican Republic, as El Corte (The Cutting),[79] directing the army to kill Haitians living on the Dominican side of the border. The army killed an estimated 12,000[80] Haitians over six days, from the night of October 2, 1937, through October 8, 1937. To avoid leaving evidence of the army's involvement, the soldiers used machetes rather than bullets.[59][78][81] The soldiers were said to have interrogated anyone with dark skin, using the shibboleth perejil (parsley) to distinguish Haitians from Afro-Dominicans when necessary; the 'r' of perejil was of difficult pronunciation for Haitians.[79] As a result of the massacre, the Dominican Republic agreed to pay Haiti US$750,000, later reduced to US$525,000.[65][76]

On November 25, 1960, Trujillo killed three of the four Mirabal sisters, nicknamed Las Mariposas (The Butterflies). The victims were Patria Mercedes Mirabal (born on February 27, 1924), Argentina Minerva Mirabal (born on March 12, 1926), and Antonia María Teresa Mirabal (born on October 15, 1935). Along with their husbands, the sisters were conspiring to overthrow Trujillo in a violent revolt. The Mirabals had communist ideological leanings as did their husbands. The sisters have received many honors posthumously and have many memorials in various cities in the Dominican Republic. Salcedo, their home province, changed its name to Provincia Hermanas Mirabal (Mirabal Sisters Province). The International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women is observed on the anniversary of their deaths.

For a long time, the U.S. and the Dominican elite supported the Trujillo government. This support persisted despite the assassinations of political opposition, the massacre of Haitians, and Trujillo's plots against other countries. The U.S. believed Trujillo was the lesser of two or more evils.[79] The U.S. finally broke with Trujillo in 1960, after Trujillo's agents attempted to assassinate the Venezuelan president, Rómulo Betancourt, a fierce critic of Trujillo.[76][82]

Post-Trujillo (1961–2000)

Trujillo was assassinated on May 30, 1961.[76] In February 1963, a democratically elected government under leftist Juan Bosch took office but it was overthrown in September. In April 1965, after 19 months of military rule, a pro-Bosch revolt broke out.[83]

Days later U.S. President Lyndon Johnson, concerned that Communists might take over the revolt and create a "second Cuba," sent the Marines, followed immediately by the U.S. Army's 82nd Airborne Division and other elements of the XVIIIth Airborne Corps, in Operation Powerpack. "We don't propose to sit here in a rocking chair with our hands folded and let the Communist set up any government in the western hemisphere," Johnson said.[84] The forces were soon joined by comparatively small contingents from the Organization of American States.[85]

All these remained in the country for over a year and left after supervising elections in 1966 won by Joaquín Balaguer. He had been Trujillo’s last puppet-president.[35][85]

Balaguer remained in power as president for 12 years. His tenure was a period of repression of human rights and civil liberties, ostensibly to keep pro-Castro or pro-communist parties out of power; 11,000 persons were killed.[86][87] His rule was criticized for a growing disparity between rich and poor. It was, however, praised for an ambitious infrastructure program, which included construction of large housing projects, sports complexes, theaters, museums, aqueducts, roads, highways, and the massive Columbus Lighthouse, completed in 1992 during a later tenure.

In 1978, Balaguer was succeeded in the presidency by opposition candidate Antonio Guzmán Fernández, of the Dominican Revolutionary Party (PRD). Another PRD win in 1982 followed, under Salvador Jorge Blanco. Under the PRD presidents, the Dominican Republic enjoyed a period of relative freedom and basic human rights.

Balaguer regained the presidency in 1986 and was re-elected in 1990 and 1994, this last time just defeating PRD candidate José Francisco Peña Gómez, a former mayor of Santo Domingo. The 1994 elections were flawed, bringing on international pressure, to which Balaguer responded by scheduling another presidential contest in 1996.[5]

That year Leonel Fernández achieved the first-ever win for the Dominican Liberation Party (PLD), which Bosch had founded in 1973 after leaving the PRD (which he also had founded). Fernández oversaw a fast-growing economy: growth averaged 7.7% per year, unemployment fell, and there were stable exchange and inflation rates.[88]

21st century

In 2000 the PRD's Hipólito Mejía won the election. This was a time of economic troubles.[88] Mejía was defeated in his re-election effort in 2004 by Leonel Fernández of the PLD. In 2008, Fernández was elected for a third term.[27] Fernández and the PLD are credited with initiatives that have moved the country forward technologically, such as the construction of the Metro Railway ("El Metro"). On the other hand, his administrations have been accused of corruption.[88]

Danilo Medina, of the PLD, was elected president in 2012 and re-elected in 2016. He campaigned on a platform of investing more in social programs and education and less in infrastructure.

Geography

The Dominican Republic is situated on the eastern part of the second largest island in the Greater Antilles, Hispaniola. It shares the island roughly at a 2:1 ratio with Haiti. The country's area is reported variously as 48,442 km2 (18,704 sq mi) (by the embassy in the United States)[2] and 48,730 km2 (18,815 sq mi),[5] making it the second largest country in the Antilles, after Cuba. The Dominican Republic's capital and largest metropolitan area Santo Domingo is on the southern coast.

There are many small offshore islands and cays that are part of the Dominican territory. The two largest islands near shore are Saona, in the southeast, and Beata, in the southwest. To the north, at distances of 100–200 kilometres (62–124 mi), are three extensive, largely submerged banks, which geographically are a southeast continuation of the Bahamas: Navidad Bank, Silver Bank, and Mouchoir Bank. Navidad Bank and Silver Bank have been officially claimed by the Dominican Republic.

The Dominican Republic has four important mountain ranges. The most northerly is the Cordillera Septentrional ("Northern Mountain Range"), which extends from the northwestern coastal town of Monte Cristi, near the Haitian border, to the Samaná Peninsula in the east, running parallel to the Atlantic coast. The highest range in the Dominican Republic – indeed, in the whole of the West Indies – is the Cordillera Central ("Central Mountain Range"). It gradually bends southwards and finishes near the town of Azua, on the Caribbean coast.

In the Cordillera Central are the four highest peaks in the Caribbean: Pico Duarte (3,098 metres or 10,164 feet above sea level), La Pelona (3,094 metres or 10,151 feet), La Rucilla (3,049 metres or 10,003 feet), and Pico Yaque (2,760 metres or 9,055 feet). In the southwest corner of the country, south of the Cordillera Central, there are two other ranges. The more northerly of the two is the Sierra de Neiba, while in the south the Sierra de Bahoruco is a continuation of the Massif de la Selle in Haiti. There are other, minor mountain ranges, such as the Cordillera Oriental ("Eastern Mountain Range"), Sierra Martín García, Sierra de Yamasá, and Sierra de Samaná.

Between the Central and Northern mountain ranges lies the rich and fertile Cibao valley. This major valley is home to the cities of Santiago and La Vega and most of the farming areas in the nation. Rather less productive are the semi-arid San Juan Valley, south of the Central Cordillera, and the Neiba Valley, tucked between the Sierra de Neiba and the Sierra de Bahoruco. Much of the land in the Enriquillo Basin is below sea level, with a hot, arid, desert-like environment. There are other smaller valleys in the mountains, such as the Constanza, Jarabacoa, Villa Altagracia, and Bonao valleys.

The Llano Costero del Caribe ("Caribbean Coastal Plain") is the largest of the plains in the Dominican Republic. Stretching north and east of Santo Domingo, it contains many sugar plantations in the savannahs that are common there. West of Santo Domingo its width is reduced to 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) as it hugs the coast, finishing at the mouth of the Ocoa River. Another large plain is the Plena de Azua ("Azua Plain"), a very arid region in Azua Province. A few other small coastal plains are in the northern coast and in the Pedernales Peninsula.

Four major rivers drain the numerous mountains of the Dominican Republic. The Yaque del Norte is the longest and most important Dominican river. It carries excess water down from the Cibao Valley and empties into Monte Cristi Bay, in the northwest. Likewise, the Yuna River serves the Vega Real and empties into Samaná Bay, in the northeast. Drainage of the San Juan Valley is provided by the San Juan River, tributary of the Yaque del Sur, which empties into the Caribbean, in the south. The Artibonito is the longest river of Hispaniola and flows westward into Haiti.

There are many lakes and coastal lagoons. The largest lake is Enriquillo, a salt lake at 45 metres (148 ft) below sea level, the lowest point in the Caribbean. Other important lakes are Laguna de Rincón or Cabral, with fresh water, and Laguna de Oviedo, a lagoon with brackish water.

Dominican Republic is located near fault action in the Caribbean. In 1946 it suffered a magnitude 8.1 earthquake off the northeast coast. This triggered a tsunami that killed about 1,800, mostly in coastal communities. The wave was also recorded at Daytona Beach, Florida, and Atlantic City, New Jersey. The area remains at risk. Caribbean countries and the United States have collaborated to create tsunami warning systems and are mapping risk in low-lying areas.

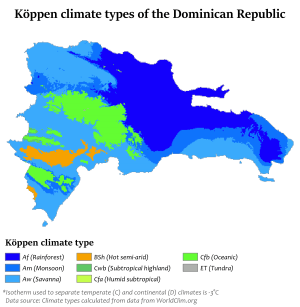

Climate

The Dominican Republic has a tropical rainforest climate in the coastal and lowland areas. Due to its diverse topography, Dominican Republic's climate shows considerable variation over short distances and is the most varied of all the Antilles. The annual average temperature is 25 °C (77 °F). At higher elevations the temperature averages 18 °C (64.4 °F) while near sea level the average temperature is 28 °C (82.4 °F). Low temperatures of 0 °C (32 °F) are possible in the mountains while high temperatures of 40 °C (104 °F) are possible in protected valleys. January and February are the coolest months of the year while August is the hottest month. Snowfall can be seen in rare occasions on the summit of Pico Duarte.[89]

The wet season along the northern coast lasts from November through January. Elsewhere the wet season stretches from May through November, with May being the wettest month. Average annual rainfall is 1,500 millimetres (59.1 in) countrywide, with individual locations in the Valle de Neiba seeing averages as low as 350 millimetres (13.8 in) while the Cordillera Oriental averages 2,740 millimetres (107.9 in). The driest part of the country lies in the west.[89]

Tropical cyclones strike the Dominican Republic every couple of years, with 65% of the impacts along the southern coast. Hurricanes are most likely between August and October.[89] The last major hurricane that struck the country was Hurricane Georges in 1998.[90]

Government and politics

The Dominican Republic is a representative democracy or democratic republic,[2][5][27] with three branches of power: executive, legislative, and judicial. The president of the Dominican Republic heads the executive branch and executes laws passed by the congress, appoints the cabinet, and is commander in chief of the armed forces. The president and vice-president run for office on the same ticket and are elected by direct vote for 4-year terms. The national legislature is bicameral, composed of a senate, which has 32 members, and the Chamber of Deputies, with 178 members.[27]

Judicial authority rests with the Supreme Court of Justice's 16 members. They are appointed by a council composed of the president, the leaders of both houses of congress, the President of the Supreme Court, and an opposition or non–governing-party member. The court "alone hears actions against the president, designated members of his Cabinet, and members of Congress when the legislature is in session."[27]

The Dominican Republic has a multi-party political system. Elections are held every two years, alternating between the presidential elections, which are held in years evenly divisible by four, and the congressional and municipal elections, which are held in even-numbered years not divisible by four. "International observers have found that presidential and congressional elections since 1996 have been generally free and fair."[27] The Central Elections Board (JCE) of nine members supervises elections, and its decisions are unappealable.[27] Starting from 2016, elections will be held jointly, after a constitutional reform.[91]

Political culture

The three major parties are the conservative Social Christian Reformist Party (Spanish: Partido Reformista Social Cristiano (PRSC)), in power 1966–78 and 1986–96; the social democratic Dominican Revolutionary Party (Spanish: Partido Revolucionario Dominicano (PRD)), in power in 1963, 1978–86, and 2000–04; and the centrist liberal and reformist Dominican Liberation Party (Spanish: Partido de la Liberación Dominicana (PLD)), in power 1996–2000 and since 2004.

The presidential elections of 2008 were held on May 16, 2008, with incumbent Leonel Fernández winning 53% of the vote.[92] He defeated Miguel Vargas Maldonado, of the PRD, who achieved a 40.48% share of the vote. Amable Aristy, of the PRSC, achieved 4.59% of the vote. Other minority candidates, which included former Attorney General Guillermo Moreno from the Movement for Independence, Unity and Change (Spanish: Movimiento Independencia, Unidad y Cambio (MIUCA)), and PRSC former presidential candidate and defector Eduardo Estrella, obtained less than 1% of the vote.

In the 2012 presidential elections the incumbent president Leonel Fernández (PLD) declined his aspirations[93] and instead the PLD elected Danilo Medina as its candidate. This time the PRD presented ex-president Hipolito Mejia as its choice. The contest was won by Medina with 51.21% of the vote, against 46.95% in favor of Mejia. Candidate Guillermo Moreno obtained 1.37% of the votes.[94]

In 2014 the Modern Revolutionary Party (Spanish: Partido revolucionario Moderno) was created[95] by a faction of leaders from the PRD and has since become the predominant opposition party, polling in second place for the upcoming May 2016 general elections.[96]

Foreign relations

The Dominican Republic has a close relationship with the United States and with the other states of the Inter-American system. The Dominican Republic has very strong ties and relations with Puerto Rico.

The Dominican Republic's relationship with neighbouring Haiti is strained over mass Haitian migration to the Dominican Republic, with citizens of the Dominican Republic blaming the Haitians for increased crime and other social problems.[97] The Dominican Republic is a regular member of the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie.

The Dominican Republic has a Free Trade Agreement with the United States, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua via the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement.[98] And an Economic Partnership Agreement with the European Union and the Caribbean Community via the Caribbean Forum.[99]

Military

Congress authorizes a combined military force of 44,000 active duty personnel. Actual active duty strength is approximately 32,000. Approximately 50% of those are used for non-military activities such as security providers for government-owned non-military facilities, highway toll stations, prisons, forestry work, state enterprises, and private businesses. The commander in chief of the military is the president.

The army is larger than the other services combined with approximately 20,000 active duty personnel, consisting of six infantry brigades, a combat support brigade, and a combat service support brigade. The air force operates two main bases, one in the southern region near Santo Domingo and one in the northern region near Puerto Plata. The navy operates two major naval bases, one in Santo Domingo and one in Las Calderas on the southwestern coast, and maintains 12 operational vessels. The Dominican Republic has the second largest military in the Caribbean region after Cuba.[27]

The armed forces have organized a Specialized Airport Security Corps (CESA) and a Specialized Port Security Corps (CESEP) to meet international security needs in these areas. The secretary of the armed forces has also announced plans to form a specialized border corps (CESEF). The armed forces provide 75% of personnel to the National Investigations Directorate (DNI) and the Counter-Drug Directorate (DNCD).[27]

The Dominican National Police force contains 32,000 agents. The police are not part of the Dominican armed forces but share some overlapping security functions. Sixty-three percent of the force serve in areas outside traditional police functions, similar to the situation of their military counterparts.[27]

Administrative divisions

The Dominican Republic is divided into 31 provinces. Santo Domingo, the capital, is designated Distrito Nacional (National District). The provinces are divided into municipalities (municipios; singular municipio). They are the second-level political and administrative subdivisions of the country. The president appoints the governors of the 31 provinces. Mayors and municipal councils administer the 124 municipal districts and the National District (Santo Domingo). They are elected at the same time as congressional representatives.[27]

Economy

The Dominican Republic is the largest economy[19] (according to the U.S. State Department and the World Bank)[27][100] in the Caribbean and Central American region. It is an upper middle-income developing country,[101] with a 2015 GDP per capita of $14,770, in PPP terms. Over the last two decades, the Dominican Republic have been standing out as one of the fastest-growing economies in the Americas – with an average real GDP growth rate of 5.4% between 1992 and 2014.[100] GDP growth in 2014 and 2015 reached 7.3 and 7.0%, respectively, the highest in the Western Hemisphere.[21] In the first half of 2016 the Dominican economy grew 7.4%.[22] As of 2015, the average wage in nominal terms is 392 USD per month ($17,829 DOP).[102]

During the last three decades, the Dominican economy, formerly dependent on the export of agricultural commodities (mainly sugar, cocoa and coffee), has transitioned to a diversified mix of services, manufacturing, agriculture, mining, and trade. The service sector accounts for almost 60% of GDP; manufacturing, for 22%; tourism, telecommunications and finance are the main components of the service sector; however, none of them accounts for more than 10% of the whole.[103]

Remittances in Dominican Republic increased to 4571.30 million USD in 2014 from 3333 million USD in 2013 (according to data reported by the Inter-American Development Bank). Economic growth takes place in spite of a chronic energy shortage,[104] which causes frequent blackouts and very high prices. Despite a widening merchandise trade deficit, tourism earnings and remittances have helped build foreign exchange reserves. The Dominican Republic is current on foreign private debt.

Following economic turmoil in the late 1980s and 1990, during which the gross domestic product (GDP) fell by up to 5% and consumer price inflation reached an unprecedented 100%, the Dominican Republic entered a period of growth and declining inflation until 2002, after which the economy entered a recession.[27]

This recession followed the collapse of the second-largest commercial bank in the country, Baninter, linked to a major incident of fraud valued at $3.5 billion. The Baninter fraud had a devastating effect on the Dominican economy, with GDP dropping by 1% in 2003 as inflation ballooned by over 27%. All defendants, including the star of the trial, Ramón Báez Figueroa (the great-grandson of President Buenaventura Báez),[105] were convicted.

According to the 2005 Annual Report of the United Nations Subcommittee on Human Development in the Dominican Republic, the country is ranked No. 71 in the world for resource availability, No. 79 for human development, and No. 14 in the world for resource mismanagement. These statistics emphasize national government corruption, foreign economic interference in the country, and the rift between the rich and poor.

The Dominican Republic has a noted problem of child labor in its coffee, rice, sugarcane, and tomato industries.[106] The labor injustices in the sugarcane industry extend to forced labor according to the U.S. Department of Labor. Three large groups own 75% of the land: the State Sugar Council (Consejo Estatal del Azúcar, CEA), Grupo Vicini, and Central Romana Corporation.[107]

Currency

The Dominican peso (DOP, or RD$)[108] is the national currency, with the United States dollar (USD), the Canadian dollar (CAD), the Swiss franc (CHF), and euros (EUR) also accepted at most tourist sites. The exchange rate to the U.S. dollar, liberalized by 1985, stood at 2.70 pesos per dollar in August 1986,[62]:p417, 428 14.00 pesos in 1993, and 16.00 pesos in 2000. Having jumped to 53.00 pesos per dollar in 2003, the rate was back down to around 31.00 pesos per dollar in 2004. As of November 2010 the rate was 37.00 pesos per dollar. In February 2015 the rate was 44.67 pesos per dollar.[108] As of February 2017 the rate was 46.72 pesos per dollar.[109]

Tourism

Tourism is one of the fueling factors in the Dominican Republic's economic growth. The Dominican Republic is the most popular tourist destination in the Caribbean. With the construction of projects like Cap Cana, San Souci Port in Santo Domingo, Casa De Campo and the Hard Rock Hotel & Casino (ancient Moon Palace Resort) in Punta Cana, the Dominican Republic expects increased tourism activity in the upcoming years.

Ecotourism has also been a topic increasingly important in this nation, with towns like Jarabacoa and neighboring Constanza, and locations like the Pico Duarte, Bahia de las Aguilas, and others becoming more significant in efforts to increase direct benefits from tourism. Most residents from other countries are required to get a tourist card, depending on the country they live in.

Infrastructure

Transportation

The Dominican Republic has Latin America's third best transportation infrastructure. The country has three national trunk highways, which connect every major town. These are DR-1, DR-2, and DR-3, which depart from Santo Domingo toward the northern (Cibao), southwestern (Sur), and eastern (El Este) parts of the country respectively. These highways have been consistently improved with the expansion and reconstruction of many sections. Two other national highways serve as spur (DR-5) or alternate routes (DR-4).

In addition to the national highways, the government has embarked on an expansive reconstruction of spur secondary routes, which connect smaller towns to the trunk routes. In the last few years the government constructed a 106-kilometer toll road that connects Santo Domingo with the country's northeastern peninsula. Travelers may now arrive in the Samaná Peninsula in less than two hours. Other additions are the reconstruction of the DR-28 (Jarabacoa – Constanza) and DR-12 (Constanza – Bonao). Despite these efforts, many secondary routes still remain either unpaved or in need of maintenance. There is currently a nationwide program to pave these and other commonly used routes. Also, the Santiago light rail system is in planning stages but currently on hold.

Bus service

There are two main bus transportation services in the Dominican Republic: one controlled by the government, through the Oficina Técnica de Transito Terrestre (OTTT) and the Oficina Metropolitana de Servicios de Autobuses (OMSA), and the other controlled by private business, among them, Federación Nacional de Transporte La Nueva Opción (FENATRANO) and the Confederacion Nacional de Transporte (CONATRA). The government transportation system covers large routes in metropolitan areas such as Santo Domingo and Santiago.

There are many privately owned bus companies, such as Metro Servicios Turísticos and Caribe Tours, that run daily routes.

Santo Domingo Metro

The Dominican Republic has a rapid transit system in Santo Domingo, the country's capital. It is the most extensive metro system in the insular Caribbean and Central American region by length and number of stations. The Santo Domingo Metro is part of a major "National Master Plan" to improve transportation in Santo Domingo as well as the rest of the nation. The first line was planned to relieve traffic congestion in the Máximo Gómez and Hermanas Mirabal Avenue. The second line, which opened in April 2013, is meant to relieve the congestion along the Duarte-Kennedy-Centenario Corridor in the city from west to east. The current length of the Metro, with the sections of the two lines open as of August 2013, is 27.35 kilometres (16.99 mi). Before the opening of the second line, 30,856,515 passengers rode the Santo Domingo Metro in 2012.[110] With both lines opened, ridership increased to 61,270,054 passengers in 2014.

Communications

The Dominican Republic has a well developed telecommunications infrastructure, with extensive mobile phone and landline services. Cable Internet and DSL are available in most parts of the country, and many Internet service providers offer 3G wireless internet service. The Dominican Republic became the second country in Latin America to have 4G LTE wireless service. The reported speeds are from 256 kbit/s or 128 kbit/s for residential services, up to 5 Mbit/s or 1 Mbit/s for residential service.

For commercial service there are speeds from 256 kbit/s up to 154 Mbit/s. (Each set of numbers denotes downstream/upstream speed; that is, to the user/from the user.) Projects to extend Wi-Fi hot spots have been made in Santo Domingo. The country's commercial radio stations and television stations are in the process of transferring to the digital spectrum, via HD Radio and HDTV after officially adopting ATSC as the digital medium in the country with a switch-off of analog transmission by September 2015. The telecommunications regulator in the country is INDOTEL (Instituto Dominicano de Telecomunicaciones).

The largest telecommunications company is Claro – part of Carlos Slim's América Móvil – which provides wireless, landline, broadband, and IPTV services. In June 2009 there were more than 8 million phone line subscribers (land and cell users) in the D.R., representing 81% of the country's population and a fivefold increase since the year 2000, when there were 1.6 million. The communications sector generates about 3.0% of the GDP.[111] There were 2,439,997 Internet users in March 2009.[112]

In November 2009, the Dominican Republic became the first Latin American country to pledge to include a "gender perspective" in every information and communications technology (ICT) initiative and policy developed by the government.[113] This is part of the regional eLAC2010 plan. The tool the Dominicans have chosen to design and evaluate all the public policies is the APC Gender Evaluation Methodology (GEM).

Electricity

Electric power service has been unreliable since the Trujillo era, and as much as 75% of the equipment is that old. The country's antiquated power grid causes transmission losses that account for a large share of billed electricity from generators. The privatization of the sector started under a previous administration of Leonel Fernández.[88] The recent investment in a "Santo Domingo–Santiago Electrical Highway" to carry 345 kW power,[114] with reduced losses in transmission, is being heralded as a major capital improvement to the national grid since the mid-1960s.

During the Trujillo regime electrical service was introduced to many cities. Almost 95% of usage was not billed at all. Around half of the Dominican Republic's 2.1 million houses have no meters and most do not pay or pay a fixed monthly rate for their electric service.[115]

Household and general electrical service is delivered at 110 volts alternating at 60 Hz. Electrically powered items from the United States work with no modifications. The majority of the Dominican Republic has access to electricity. Tourist areas tend to have more reliable power, as do business, travel, healthcare, and vital infrastructure.[116] Concentrated efforts were announced to increase efficiency of delivery to places where the collection rate reached 70%.[117] The electricity sector is highly politicized. Some generating companies are undercapitalized and at times unable to purchase adequate fuel supplies.[27]

Water supply and sanitation

The Dominican Republic has achieved impressive increases in access to water supply and sanitation over the past two decades. However, the quality of water supply and sanitation services remains poor, despite the country's high economic growth during the 1990s. Although the coverage of improved water sources and improved sanitation is with 86% respectively 83% relatively high, there are substantial regional differences. Poor households exhibit lower levels of access: only 56% of poor households are connected to water house connections as opposed to 80% of non-poor households. Just 20% of poor households have access to sewers, as opposed to 50% for the non-poor.[118]

Society

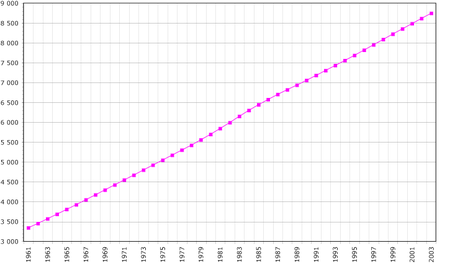

Demographics

The Dominican Republic's population was 9,760,000 in 2007.[119] In 2010 31.2% of the population was under 15 years of age, with 6% of the population over 65 years of age.[120] There were 103 males for every 100 females in 2007.[5] The annual population growth rate for 2006–2007 was 1.5%, with the projected population for the year 2015 being 10,121,000.[119]

The population density in 2007 was 192 per km² (498 per sq mi), and 63% of the population lived in urban areas.[121] The southern coastal plains and the Cibao Valley are the most densely populated areas of the country. The capital city Santo Domingo had a population of 2,907,100 in 2010.[122]

Other important cities are: Santiago de los Caballeros (pop. 745,293), La Romana (pop. 214,109), San Pedro de Macorís (pop. 185,255), Higüey (153,174), San Francisco de Macorís (pop. 132,725), Puerto Plata (pop. 118,282), and La Vega (pop. 104,536). Per the United Nations, the urban population growth rate for 2000–2005 was 2.3%.[122]

Ethnic groups

The Dominican Republic's population is 73% of racially mixed origin, 16% White, and 11% Black.[5] Ethnic immigrant groups in the country include West Asians—mostly Lebanese, Syrians, and Palestinians.[123]

Numerous immigrants have come from other Caribbean countries, as the country has offered economic opportunities. There are about 32,000 Jamaicans living in the Dominican Republic.[124] There is an increasing number of Puerto Rican immigrants, especially in and around Santo Domingo; they are believed to number around 10,000.[125][126] There are over 700,000 people of Haitian descent, including a generation born in the Dominican Republic.

East Asians, primarily ethnic Chinese and Japanese, can also be found.[123] Europeans are represented mostly by Spanish whites but also with smaller populations of German Jews, Italians, Portuguese, British, Dutch, Danes, and Hungarians.[123][127][128] Some converted Sephardic Jews from Spain were part of early expeditions; only Catholics were allowed to come to the New World.[129] Later there were Jewish migrants coming from Iberia and Europe in the 1700s.[130] Some managed to reach the Caribbean as refugees during and after the Second World War.[131][132][133] Some Sephardic Jews reside in Sosúa while others are dispersed throughout the country. Self-identified Jews number about 3,000; other Dominicans may have some Jewish ancestry because of marriages among converted Jewish Catholics and other Dominicans since the colonial years. Some Dominicans born in the United States now reside in the Dominican Republic, creating a kind of expatriate community.[134]

Languages

The population of the Dominican Republic is mostly Spanish-speaking. The local variant of Spanish is called Dominican Spanish, which closely resembles other Spanish vernaculars in the Caribbean and the Canarian Spanish. In addition, it borrowed words from indigenous Caribbean languages particular to the island of Hispaniola.[135][136] Schools are based on a Spanish educational model; English and French are mandatory foreign languages in both private and public schools,[137] although the quality of foreign languages teaching is poor.[138] Some private educational institutes provide teaching on other languages, notably Italian, Japanese, and Mandarin.[139][140]

Haitian Creole is the largest minority language in the Dominican Republic and is spoken by Haitian immigrants and their descendants.[141] There is a community of a few thousand people whose ancestors spoke Samaná English in the Samaná Peninsula. They are the descendants of formerly enslaved African Americans who arrived in the nineteenth century, but only a few elders speak the language today.[142] Tourism, American pop culture, the influence of Dominican Americans, and the country's economic ties with the United States motivate other Dominicans to learn English. The Dominican Republic is ranked 2nd in Latin America and 23rd in the World on English proficiency.[143][144]

| Language | Total % | Urban % | Rural % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish | 98.00 | 97.82 | 98.06 |

| French | 1.19 | 0.39 | 1.44 |

| English | 0.57 | 0.96 | 0.45 |

| Arabic | 0.09 | 0.35 | 0.01 |

| Italian | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.006 |

| Other language | 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.04 |

Population centres

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Province | Pop. | |||||||

| Santo Domingo  Santiago |

1 | Santo Domingo | Distrito Nacional | 2,908,607 |  La Vega  San Cristóbal | ||||

| 2 | Santiago | Santiago | 553,091 | ||||||

| 3 | La Vega | La Vega | 210,736 | ||||||

| 4 | San Cristóbal | San Cristóbal | 209,165 | ||||||

| 5 | San Pedro de Macorís | San Pedro de Macorís | 205,911 | ||||||

| 6 | San Francisco de Macorís | Duarte | 138,167 | ||||||

| 7 | La Romana | La Romana | 130,842 | ||||||

| 8 | Higüey | La Altagracia | 128,120 | ||||||

| 9 | Puerto Plata | Puerto Plata | 122,186 | ||||||

| 10 | Moca | Espaillat Province | 92,111 | ||||||

Religion

95.0% Christians

2.6% No religion

2.2% Other religions [147]

As of 2014, 57% of the population (5.7 million) identified themselves as Roman Catholics and 23% (2.3 million) as Protestants (in Latin American countries, Protestants are usually called Evangelicos due to them being overwhelmingly Evangelical Protestant or Pentecostal). Recent immigration as well as proselytizing has brought other religions, with the following shares of the population: Spiritist: 2.2%,[148] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: 1.1%,[149] Buddhist: 0.1%, Bahá'í: 0.1%,[148] Chinese Folk Religion: 0.1%,[148] Islam: 0.02%, Judaism: 0.01%. The Dominican Republic has two patroness saints: Nuestra Señora de la Altagracia (Our Lady Of High Grace) and Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes (Our Lady Of Mercy).

The Catholic Church began to lose popularity in the late 19th century. This was due to a lack of funding, priests, and support programs. During the same time, Evangelicalism began to gain support.

The Dominican Republic has historically granted extensive religious freedom. In the 1950s restrictions were placed upon churches by the government of Trujillo. Letters of protest were sent against the mass arrests of government adversaries. Trujillo began a campaign against the Catholic Church and planned to arrest priests and bishops who preached against the government. This campaign ended before it was put into place, with his assassination.

During World War II a group of Jews escaping Nazi Germany fled to the Dominican Republic and founded the city of Sosúa. It has remained the center of the Jewish population since.[150]

20th century immigration

In the 20th century, many Arabs (from Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine),[151] Japanese, and, to a lesser degree, Koreans settled in the country as agricultural laborers and merchants. The Chinese companies found business in telecom, mining, and railroads. The Chinese Dominican population is 50,000. The Arab community is rising at an increasing rate and is estimated at 80,000.[151] There are around 1,900 Japanese immigrants, who mostly work in the business districts and markets. There is a Korean population of 500.

In addition, there are descendants of immigrants who came from other Caribbean islands, including St. Kitts and Nevis, Antigua, St. Vincent, Montserrat, Tortola, St. Croix, St. Thomas, and Guadeloupe. They worked on sugarcane plantations and docks and settled mainly in the cities of San Pedro de Macorís and Puerto Plata. Puerto Rican, and to a lesser extent, Cuban immigrants fled to the Dominican Republic from the mid-1800s until about 1940 due to a poor economy and social unrest in their respective home countries. Many Puerto Rican immigrants settled in Higüey, among other cities, and quickly assimilated due to similar culture. Before and during World War II, 800 Jewish refugees moved to the Dominican Republic.[128]

Haitian immigration

Haiti is the neighboring nation to the Dominican Republic and is considerably poorer, less developed and is additionally the least developed country in the western hemisphere. In 2003, 80% of all Haitians were poor (54% living in abject poverty) and 47.1% were illiterate. The country of nine million people also has a fast growing population, but over two-thirds of the labor force lack formal jobs. Haiti's per capita GDP (PPP) was $1,300 in 2008, or less than one-sixth of the Dominican figure.[5][152]

As a result, hundreds of thousands of Haitians have migrated to the Dominican Republic, with some estimates of 800,000 Haitians in the country,[25] while others put the Haitian-born population as high as one million.[153] They usually work at low-paying and unskilled jobs in building construction and house cleaning and in sugar plantations.[154] There have been accusations that some Haitian immigrants work in slavery-like conditions and are severely exploited.[155]

Due to the lack of basic amenities and medical facilities in Haiti a large number of Haitian women, often arriving with several health problems, cross the border to Dominican soil. They deliberately come during their last weeks of pregnancy to obtain medical attention for childbirth, since Dominican public hospitals do not refuse medical services based on nationality or legal status. Statistics from a hospital in Santo Domingo report that over 22% of childbirths are by Haitian mothers.[156]

Haiti also suffers from severe environmental degradation. Deforestation is rampant in Haiti; today less than 4 percent of Haiti’s forests remain, and in many places the soil has eroded right down to the bedrock.[157] Haitians burn wood charcoal for 60% of their domestic energy production. Because of Haiti running out of plant material to burn, Haitians have created an illegal market for coal on the Dominican side. Conservative estimates calculate the illegal movement of 115 tons of charcoal per week from the Dominican Republic to Haiti. Dominican officials estimate that at least 10 trucks per week are crossing the border loaded with charcoal.[158]

In 2005, Dominican President Leonel Fernández criticized collective expulsions of Haitians as having taken place "in an abusive and inhuman way."[159] After a UN delegation issued a preliminary report stating that it found a profound problem of racism and discrimination against people of Haitian origin, Dominican Foreign Minister Carlos Morales Troncoso issued a formal statement denouncing it, asserting that "our border with Haiti has its problems[;] this is our reality and it must be understood. It is important not to confuse national sovereignty with indifference, and not to confuse security with xenophobia."[160]

Children of Haitian immigrants are often stateless and denied services, as their parents are denied Dominican nationality, being deemed transient residents due to their illegal or undocumented status; the children, though often eligible for Haitian nationality,[161] are denied it by Haiti because of a lack of proper documents or witnesses.[162][163][164][165]

Emigration

The first of three late-20th century emigration waves began in 1961 after the assassination of dictator Trujillo,[166] due to fear of retaliation by Trujillo's allies and political uncertainty in general. In 1965 the United States began a military occupation of the Dominican Republic to end a civil war. Upon this, the U.S. eased travel restrictions, making it easier for Dominicans to obtain U.S. visas.[167] From 1966 to 1978, the exodus continued, fueled by high unemployment and political repression. Communities established by the first wave of immigrants to the U.S. created a network that assisted subsequent arrivals.[168]

In the early 1980s, underemployment, inflation, and the rise in value of the dollar all contributed to a third wave of emigration from the Dominican Republic. Today, emigration from the Dominican Republic remains high.[168] In 2012 there were approximately 1.7 million people of Dominican descent in the U.S., counting both native- and foreign-born.[169] There was also a growing Dominican immigration to Puerto Rico, with nearly 70,000 Dominicans living there as of 2010. Although that number is slowly decreasing and immigration trends have reversed because of Puerto Rico's economic crisis as of 2016.

Health

In 2007 the Dominican Republic had a birth rate of 22.91 per 1000 and a death rate of 5.32 per 1000.[5] Youth in the Dominican Republic is the healthiest age group.

The prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the Dominican Republic in 2011 stood at approximately 0.7%, which is relatively low by Caribbean standards, with an estimated 62,000 HIV/AIDS-positive Dominicans.[170] In contrast neighboring Haiti has an HIV/AIDS rate more than double that of the Dominican Republic. A mission based in the United States has been helping to combat AIDS in the country.[171] Dengue fever has become endemic to the republic, cases of malaria, and Zika virus.[172][173]

The practice of abortion is illegal in all cases in the Dominican Republic, a ban that includes conceptions following rape, incest, and situations where the health of the mother is in danger, even if life-threatening.[174] This ban was reiterated by the Dominican government in a September 2009 provision of a constitutional reform bill.[175]

Education

Primary education is regulated by the Ministry of Education, with education being a right of all citizens and youth in the Dominican Republic.[176]

Preschool education is organized in different cycles and serves the 2–4 age group and the 4–6 age group. Preschool education is not mandatory except for the last year. Basic education is compulsory and serves the population of the 6–14 age group. Secondary education is not compulsory, although it is the duty of the state to offer it for free. It caters to the 14–18 age group and is organized in a common core of four years and three modes of two years of study that are offered in three different options: general or academic, vocational (industrial, agricultural, and services), and artistic.

The higher education system consists of institutes and universities. The institutes offer courses of a higher technical level. The universities offer technical careers, undergraduate and graduate; these are regulated by the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Technology.[177]

Crime

In 2012 the Dominican Republic had a murder rate of 22.1 per 100,000 population.[178] There was a total of 2,268 murders in the Dominican Republic in 2012.[178]

The Dominican Republic has become a trans-shipment point for Colombian drugs destined to Europe as well as the United States and Canada.[5][179] Money-laundering via the Dominican Republic is favored by Colombian drug cartels for the ease of illicit financial transactions.[5] In 2004 it was estimated that 8% of all cocaine smuggled into the United States had come through the Dominican Republic.[180] The Dominican Republic responded with increased efforts to seize drug shipments, arrest and extradite those involved, and combat money-laundering.

The often light treatment of violent criminals has been a continuous source of local controversy. In April 2010, five teenagers ages 15 to 17 shot and killed two taxi drivers and killed another five by forcing them to drink drain-cleaning acid. On September 24, 2010, the teens were sentenced to only 3–5 year prison terms, despite the protests of the taxi drivers' families.[181]

Culture

Culture and customs of the Dominican people have a European cultural basis, influenced by both African and native Taíno elements;[182] culturally the Dominican Republic is among the most-European countries in Spanish America, alongside with Puerto Rico, Cuba, Central Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay.[182]

European, African, and Taíno cultural elements are exposed in cuisine, architecture, language, family structure, religion, and music. Many Arawak/Taíno names and words are used in daily conversation and for many foods native to the Dominican Republic.[5]

Architecture

The architecture in the Dominican Republic represents a complex blend of diverse cultures. The deep influence of the European colonists is the most evident throughout the country. Characterized by ornate designs and baroque structures, the style can best be seen in the capital city of Santo Domingo, which is home to the first cathedral, castle, monastery, and fortress in all of the Americas, located in the city's Colonial Zone, an area declared as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.[183][184] The designs carry over into the villas and buildings throughout the country. It can also be observed on buildings that contain stucco exteriors, arched doors and windows, and red tiled roofs.

The indigenous peoples of the Dominican Republic have also had a significant influence on the architecture of the country. The Taíno people relied heavily on the mahogany and guano (dried palm tree leaf) to put together crafts, artwork, furniture, and houses. Utilizing mud, thatched roofs, and mahogany trees, they gave buildings and the furniture inside a natural look, seamlessly blending in with the island’s surroundings.

Lately, with the rise in tourism and increasing popularity as a Caribbean vacation destination, architects in the Dominican Republic have now begun to incorporate cutting-edge designs that emphasize luxury. In many ways an architectural playground, villas and hotels implement new styles, while offering new takes on the old. This new style is characterized by simplified, angular corners and large windows that blend outdoor and indoor spaces. As with the culture as a whole, contemporary architects embrace the Dominican Republic's rich history and various cultures to create something new. Surveying modern villas, one can find any combination of the three major styles: a villa may contain angular, modernist building construction, Spanish Colonial-style arched windows, and a traditional Taino hammock in the bedroom balcony.

Cuisine

Dominican cuisine is predominantly Spanish, Taíno, and African. The typical cuisine is quite similar to what can be found in other Latin American countries, but many of the names of dishes are different. One breakfast dish consists of eggs and mangú (mashed, boiled plantain). For heartier versions, mangú is accompanied by deep-fried meat (Dominican salami, typically) and/or cheese. Similar to Spanish tradition, lunch is generally the largest and most important meal of the day. Lunch usually consists of rice, meat (such as chicken, beef, pork, or fish), beans, and a side portion of salad. "La Bandera" (literally "The Flag") is the most popular lunch dish; it consists of meat and red beans on white rice. Sancocho is a stew often made with seven varieties of meat.

Meals are mostly split into three courses throughout the day, as in any other country. One has breakfast, which can be served 8–9 a.m. Then there is lunch, which is usually the heaviest meal of the day and is usually served at noon sharp. The last meal of the day, which is dinner, is usually served by 5:30 or 6 p.m.

Meals tend to favor meats and starches over dairy products and vegetables. Many dishes are made with sofrito, which is a mix of local herbs used as a wet rub for meats and sautéed to bring out all of a dish's flavors. Throughout the south-central coast, bulgur, or whole wheat, is a main ingredient in quipes or tipili (bulgur salad). Other favorite Dominican foods are chicharrón, yuca, casabe, pastelitos (empanadas), batata, yam, pasteles en hoja, chimichurris, tostones.

Some treats Dominicans enjoy are arroz con leche (or arroz con dulce), bizcocho dominicano (lit. Dominican cake), habichuelas con dulce, flan, frío frío (snow cones), dulce de leche, and caña (sugarcane). The beverages Dominicans enjoy are Morir Soñando, rum, beer, Mama Juana,[186] batida (smoothie), jugos naturales (freshly squeezed fruit juices), mabí, coffee, and chaca (also called maiz caqueao/casqueado, maiz con dulce and maiz con leche), the last item being found only in the southern provinces of the country such as San Juan.

Music and dance

Musically, the Dominican Republic is known for the world popular musical style and genre called merengue,[187]:376–7 a type of lively, fast-paced rhythm and dance music consisting of a tempo of about 120 to 160 beats per minute (though it varies) based on musical elements like drums, brass, chorded instruments, and accordion, as well as some elements unique to the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, such as the tambora and güira.

Its syncopated beats use Latin percussion, brass instruments, bass, and piano or keyboard. Between 1937 and 1950 merengue music was promoted internationally by Dominican groups like Billo's Caracas Boys, Chapuseaux and Damiron "Los Reyes del Merengue," Joseito Mateo, and others. Radio, television, and international media popularized it further. Some well known merengue performers are Wilfrido Vargas, Johnny Ventura, singer-songwriter Los Hermanos Rosario, Juan Luis Guerra, Fernando Villalona, Eddy Herrera, Sergio Vargas, Toño Rosario, Milly Quezada, and Chichí Peralta.

Merengue became popular in the United States, mostly on the East Coast, during the 1980s and 1990s,[187]:375 when many Dominican artists residing in the U.S. (particularly New York) started performing in the Latin club scene and gained radio airplay. They included Victor Roque y La Gran Manzana, Henry Hierro, Zacarias Ferreira, Aventura, and Milly Jocelyn Y Los Vecinos. The emergence of bachata, along with an increase in the number of Dominicans living among other Latino groups in New York, New Jersey, and Florida, has contributed to Dominican music's overall growth in popularity.[187]:378

.jpg)

Bachata, a form of music and dance that originated in the countryside and rural marginal neighborhoods of the Dominican Republic, has become quite popular in recent years. Its subjects are often romantic; especially prevalent are tales of heartbreak and sadness. In fact, the original name for the genre was amargue ("bitterness," or "bitter music," or blues music), until the rather ambiguous (and mood-neutral) term bachata became popular. Bachata grew out of, and is still closely related to, the pan-Latin American romantic style called bolero. Over time, it has been influenced by merengue and by a variety of Latin American guitar styles.

Palo is an Afro-Dominican sacred music that can be found throughout the island. The drum and human voice are the principal instruments. Palo is played at religious ceremonies—usually coinciding with saints' religious feast days—as well as for secular parties and special occasions. Its roots are in the Congo region of central-west Africa, but it is mixed with European influences in the melodies.[188]

Salsa music has had a great deal of popularity in the country. During the late 1960s Dominican musicians like Johnny Pacheco, creator of the Fania All Stars, played a significant role in the development and popularization of the genre.

Dominican rock is also popular. Many, if not the majority, of its performers are based in Santo Domingo and Santiago.

Fashion