Nainsukh

Nainsukh (literally "Joy of the Eyes"; c. 1710[1] – 1778) was an Indian painter. He was the younger son of the painter Pandit Seu and, like his older brother Manaku, was an important practitioner of Pahari painting, and has been called "one of the most original and brilliant of Indian painters".[2]

Around 1740 he left the family workship in Guler and moved to Jasrota, where he painted most of his works for the local Rajput ruler Mian Zorowar Singh and his son Balwant Singh until the latter's death in 1763. This is the best known and documented phase of his career. Through his adaptation of elements of Mughal painting, he was a central force in the development of Pahari painting in the middle of the eighteenth century, bringing Mughal elements into what had been a school mainly concerned with Hindu religious subjects.[3] In his final phase at Basholi, from about 1765 until his death in 1778, Nainsukh returned to religious subject matter, but retaining his stylistic innovations. By the end of his career, with an active family workshop continuing his style, he was probably not executing the works himself anymore, but leaving them to his children and nephew as his artistic heirs. Such works are often ascribed to the Family of Nainsukh.[4]

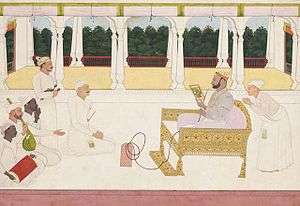

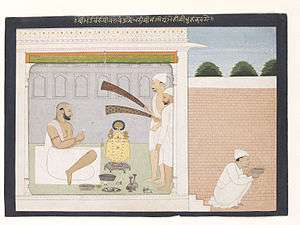

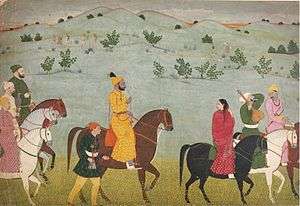

According to B.N. Goswamy, the leading scholar of Nainsukh, "Devices and mannerisms associated with Nainsukh include: a preference for uncoloured grounds; shading through a light wash that imparts volume and weight to figures and groups; a fine horizontal line that separates ground from background; a rich green in which his landscapes are usually bathed; a bush with flat circular leaves that he often introduces; a peculiar loop of the long stem of a hooka; and a minor figure often introduced in a two-thirds profile."[5]

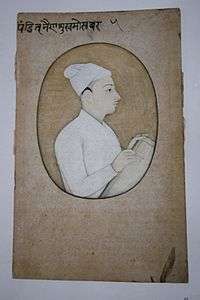

Although a great part of his work may be lost, around a hundred works by Nainsukh survive, many in both Indian and Western museums. Four of these bear his signature, and several have inscribed titles or comments.[6] Unusually for Pahari painting, some are dated.[7] There are at least two self-portraits, one from early in his career, and the other in a group scene with Balwant Singh, who is looking at a miniature, with the artist seated below him. Nainsukh peers over the raja's shoulder, perhaps offering his comments on the work, or ready to do so.[8]

Early life

Nainsukh was born c. 1710 in Guler in modern Himachal Pradesh, India, then the capital of the pocket Guler State in the far north of India, in the foothills of the Himalayas. Here his father subsequently established a painting workshop. Along with his brother who was around ten years older than him, he was trained by his father in all aspects of painting from an early age. At this very time, examples of Moghul painting were increasingly coming to the valleys of the west Himalayas, and it seems probable that Nainsukh came into contact with the works of Mughul painters early on. Possibly he had worked at a Mughal court, where Hindu artists were common.[9]

Unlike his stylistically more conservative brother Manaku, who remained in Guler and closely conformed to the style of his father Seu,[10] Nainsukh introduced many of the novel elements of Moghul painting into the traditional Pahari style employed by his family. His early work is very poorly documented, and his distinctive style emerges almost fully formed in the next phase of his career.[11]

Jasrota and Raja Balwant Singh

Around 1740, Nainsukh left his father's workshop in Guler and moved to Jasrota. It is unknown whether he made this move because of his stylistic innovations or for economic reasons (Guler was probably too small for two painters of the calibre of Manaku and Nainsukh). In the small but wealthy principality of Jasrota, Nainsukh worked for various patrons.[12]

The most important was Raja Balwant Singh (1724–1763), who employed him for almost twenty years, until his untimely death. His work for Balwant Singh is his most celebrated, showing unusually intimate, informal, and sometimes downright unflattering scenes of the raja going about his daily round of pleasures. Balwant Singh ranked very low in the ranks of Hindu princes, and was barely a ruler as opposed to a landowner.[13] He came from the Dogra dynasty and was the younger brother of the able Raja Renjit Dev of Jammu (1728–1780), who introduced social reforms such as a ban on sati (immolation of the wife on the pyre of the husband) and female infanticide. The hill states gained in prosperity from the turmoil to the south after the capture of Dehli by the Persian Nadir Shah in 1739 diverted trade routes their way.[14]

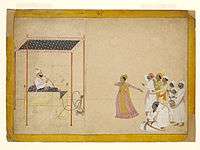

The relationship between the art-loving Balwant Singh and Nainsukh must have been very close, since Nainsukh seems to have been employed by him often and able to see and record intimate scenes of his everyday life. Balwant Singh must have lacked the normal attitude of other Indian royalty to only allow images to be produced that displayed the magnificence of his life; who between patron and painter first suggested this very informal approach is unknown. As well as some more conventional scenes, such as showing the raja hunting with a retinue or watching dancers, paintings by Nainsukh show the raja getting his beard trimmed, writing a letter, performing a puja, looking out of a palace window, sitting in front of the fire wrapped in a blanket, or smoking a hookah and inspecting a painting.[15] When Balwant Singh had to spend a period in exile in Guler Nainsukh accompanied him.[16]

It is characteristic of Nainsukh that he captures such specific situations and settings with great sensitivity. In his depictions of scenes, he moved away from stylised types in favour of realistic depictions.[17] In his naturalistic depiction of buildings and books and his efforts to depict depth, Nainsukh shows the influence of his study of works by Mughal painters. Intimate depictions of Rajput reulers were not entirely unprecedented; Raja Sidhi Sen, 10th Raja of Mandi (died 1727) had had many images of himself painted, but these emphasized what was evidently a very impressive physique, and evoked the tradition of the mahapurusha, or supernaturally perfect being. In one portrait, according to B.N. Goswamy, the raja "combines an extreme informality of appearance with great majesty of bearing", a very different effect from that of Nainsukh's paintings.[18]

The close relationship between Nainsukh and Balwant Singh is also shown by the fact that after his master's early death in 1763, he took his ashes to Haridwar along with his family's possessions, as he recorded in a long entry in the register of the pilgrimage's destination, including a drawing in pen.[19] Haridwar is one of the Sapta Puri or "Seven Holy Places" of Hinduism, and the ashes were to be cast on the river Ganges in a common funerary ritual.[20] This register record is an important source for the reconstruction of Nainsukh's life and work, which was previously clouded by considerable uncertainty, and his entry demonstrates the growing perception by artists of their importance. He also painted a miniature which probably shows the raja's ashes, ceremonially arranged in a screen tent in the countryside with two attendants, presumably at a resting place while on their way to Haridwar.[21]

Basholi, and the family workshop

_Late_18_cent%2C_Boston_MFA.jpg)

After Bawant Singh's death in 1763, around 1765 Nainsukh moved and entered the service of Amrit Pal (ruled 1757–1778),[22] a nephew of Balwant Singh and ruler of Basohli, a very devout Hindu who eventually abdicated the throne in order to devote himself to a life of meditation. For him, Nainsukh produced entirely different kinds of work, turning to the more typical Pahari subject matter of illustrating poems recounting the stories from the great Hindu religious epics. His later work is less well known than that of his Jasrota period, and in the opinion of many scholars under-rated.[23] He began to make drawings for a set of illustrations to the Gita Govinda, a famous poem on the earthly exploits of Krishna. Some late sheets by Nainsukh that were not taken beyond the stage of preliminary drawings have comments by priests and scholars on the appropriateness of the images and their faithfulness to the texts they illustrate. This indicates that the religious function of such illustrations remained important.[24]

In the family workshop which he headed in Basohli toward the end of his life, Nainsukh appear to have collaborated with his nephew Fattu (c. 1725 – 1785, son of Manaku) and his youngest son Ranjha (c. 1750 – 1830). He had three other sons: Kama (c. 1735 – c. 1810), Gaudhu (c. 1740 – 1820) and Nikka (c. 1745 – 1833).[25] Nainsukh died in Basholi in 1778.[26] Members of the family spread out in the region, carrying the family style throughout the hills.[27]

They too became painters who continued to work in the naturalistic and graceful Pahari style developed by Nainsukh. These are often attributed to the "Family of Nainsukh", as individual artists are hard to identify. The family workshop continued into the 19th century, and art historians tend to divide their work into categories such as the "first generation after Nainsukh" (or "after Nainsukh and Manaku").[28]

Nainsukh the film (2010)

.jpg)

In 2007 Amit Dutta started collaborating with the art historian Dr Eberhard Fischer and eventually directed his major work, the feature film ‘Nainsukh’ in 2010. The film is based on the biography of an 18th-century master painter of the same name belonging to the region. It premiered at the 67th Venice Film Festival, was presented in the ‘World Cinema Spotlight’ section of the San Francisco Film Festival, was showcased in MoMA, New York and travelled widely to many festivals including Rotterdam, Beijing and Vancouver Film Festivals among others. The ‘Film Comment’ magazine had rated ‘Nainsukh’ as one of the top ten films of the 67th Venice film festival.

Nainsukh has received a great deal of appreciation from both film and art critics. Prof. Dr. Milo C. Beach, the eminent American art historian, director emeritus Freer Gallery of Art, Washington DC., author of several authoritative books on Indian paintings wrote:

"The images of NAINSUKH are stunning. The comparisons with the paintings could not be more clear, but what astonishes me most is the ability of Amit Dutta to compose those images, and even more, to light them. The lighting is breathtaking. It tells you why Nainsukh would have taken such care with details, maybe especially with the folds of cloth…I think that this will do more for public interest in Indian painting that all the many scholarly essays.... What an achievement!" (If I were teaching, I would buy a copy of the film immediately to show in every class... )

Nainsukh has been widely discussed by critics for its unique formal qualities which evade categorisations. The film is said to be balancing between documentary approach and playful plot, developing its own visual language by interpreting as well as questioning Indian art history and one of its greatest artists.[1] While deeply rooted in Indian tradition and philosophy,[12] the film is also seen by eminent critic Olaf Moller as a "thought-provoking investigation into the slippery, ever-changing nature of realism, its representation in the arts. A true masterpiece of Indian modernism." [13]

With no considerable dialogue, the almost silent film is considered to create "a hypnotic fusion of imagery and sound that conjures up a lost age".[14] George Heymont of Huffington Post also observes the lack of dialogue and calls the film "visually stunning and acoustically stimulating that its beauty can often take the viewer’s breath away"[15] The film contains meticulous recreations of Nainsukh's miniatures through compositions set amidst the ruins of the Jasrota palace where the artist was retained. Galina Stoletneya remarks that "By harmoniously juxtaposing the gorgeous visuals with outstanding sound design, the filmmaker produces a unique work of art—a living painting itself—that stands on its own"[16]

Max Goldberg of San Francisco Film Society observes that the film pays close attention to the finesse of Naisukh’s brushwork and his observant images of the patron’s more informal moments like smoking and beard-trimming. He adds that "When the filmmaker reconstructs one of Nainsukh’s more complexly staged scenes—as in the hunting of a tiger clutching its human prey—his cinematic technique of isolating different elements of a single scene evokes the dynamic register of imagination and realism animating the artist’s deceptively flat pictures."[17]

The Ferroni Brigade group of film critics had nominated it as one of the best films of the 67th Venice film festival.[18]

.jpg) The Musical Mode, Surmananda

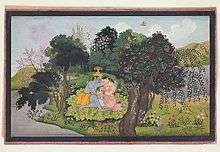

The Musical Mode, Surmananda.jpg) The Musical Mode, Gauri

The Musical Mode, Gauri Raja Balwant Singh watches performers

Raja Balwant Singh watches performers.jpg)

Notes

- ↑ Crill and Jariwala, 140 say "c. 1710–20" on the birth date, see also Pahari-Meister, p. 268.

- ↑ Kossak, 99

- ↑ Grove; Guy, 160; Harle, 411-12

- ↑ Beach, 199–200

- ↑ Grove

- ↑ A list of his works in B.N. Goswamy, Eberhard Fischer: Nainsukh of Guler. In: Milo C. Beach, Eberhard Fischer, B.N. Goswamy (Hrsg.): Masters of Indian Painting. Artibus Asiae Publishers, Zürich 2011, Vol. 2, 689–694.

- ↑ Harle, 411

- ↑ The latter painting (Museum Reitberg, Zurich) was exhibited in two recent exhibitions: #43 in London, Crill and Jariwala, 140–141, and # 83 in New York, Guy, 162; a detail of the earlier is shown at Guy, 160

- ↑ Crill and Jaliwala, 35–36; Grove

- ↑ Guy, 153–159

- ↑ Beach, 196–202; Grove; Crill and Jaliwala, 35–36

- ↑ Guy, 160

- ↑ Grove; Crill and Jariwala, 140; Harle, 411; Reila. Balwant Singh's exact status is rather confused.

- ↑ Harle, 411

- ↑ Grove; Crill and Jariwala, 36–37, 140; Harle, 411-12

- ↑ Guy, 162

- ↑ Grove; Crill and Jariwala, 140

- ↑ B.N. Goswamy, "Raja Sidhi Sen of Mandi; An Informal Portrait", in The Spirit of Indian Painting: Close Encounters with 100 Great Works 1100–1900, 2014, Penguin UK, ISBN 9351188620, 9789351188629

- ↑ Grove, see also B. N. Goswamy: Pahari Painting: The Family as the Basis of Style. In: Marg. Vol 21, No. 4, 1968, pp. 17–62 & Pahari-Meister, pp. 269–270.

- ↑ Guy, 163, # 84, online

- ↑ Guy, 163, # 84, online

- ↑ Grove

- ↑ Kossak, 99

- ↑ Beach, 202

- ↑ Pahari-Meister, 307.

- ↑ Kossak, 99

- ↑ Beach, 199

- ↑ As in Guy, #s 87–94; Grove

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nainsukh. |

- Beach, Milo Cleveland, Mughal and Rajput Painting, Part 1, Volume 3, The New Cambridge History of India, 1992, Cambridge University Press

- Crill, Rosemary, and Jariwala, Kapil. The Indian Portrait, 1560–1860, National Portrait Gallery, London, 2010, ISBN 9781855144095

- "Grove", B. N. Goswamy. "Nainsukh." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed 7 June 2015, subscription required

- Guy, John, Britschgi, Jorrit, Wonder of the Age: Master Painters of India, 1100–1900, 2011, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 1588394301, 9781588394309

- B.N. Goswamy, Eberhard Fischer: Pahari-Meister: Höfische Malerei aus den Bergen Nord-Indiens. Museum Rietberg, Zürich 1990, ISBN 3-907070-30-5.

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Kossak, Steven. (1997). Indian court painting, 16th–19th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870997831

- Reila, Anil, The Indian Portrait: An artistic journey from miniature to modern, 2010, Archer Art Gallery, google books

Further reading

- B.N. Goswamy, Eberhard Fischer: "Nainsukh of Guler", in: Milo C. Beach, Eberhard Fischer, B.N. Goswamy (Ed.): Masters of Indian Painting, Artibus Asiae Publishers, Zürich 2011, ISBN 978-3-907077-50-4, pp. 659–686 (Artibus Asiae: Supplementum. Vol 48.2).

- B.N. Goswamy: Nainsukh of Guler: A great Indian Painter from a Small Hill-State. Museum Rietberg, Zürich 1997, ISBN 3-907070-76-3 (Artibus Asiae: Supplementum. Vol XLI).