Nikolai Vavilov

| Nikolai Vavilov | |

|---|---|

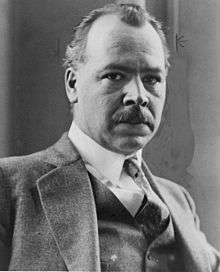

Nikolai Vavilov in 1933 | |

| Born |

Nikolaj Ivanovic Vavilov 25 November 1887 Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died |

26 January 1943 (aged 55) Saratov, RSFSR, Soviet Union |

| Citizenship | USSR |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Fields |

Botany Genetics |

| Institutions |

Saratov Agricultural Institute Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences |

| Alma mater | Moscow Agricultural Institute |

| Known for | Centres of origin |

| Notable awards |

Lenin Prize Fellow of the Royal Society[1] |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Vavilov |

Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov ForMemRS[1] (Russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Вави́лов; IPA: [nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ vɐˈvʲiləf]) (November 25 [O.S. November 13] 1887 – January 26, 1943) was a prominent Russian and Soviet botanist and geneticist best known for having identified the centres of origin of cultivated plants. He devoted his life to the study and improvement of wheat, corn, and other cereal crops that sustain the global population.[2][3][4][5][6]

Life

Vavilov was born into a merchant family in Moscow, the older brother of renowned physicist Sergey Ivanovich Vavilov. "The son of a Moscow merchant who'd grown up in a poor rural village plagued by recurring crop failures and food rationing, Vavilov was obsessed from an early age with ending famine in both his native Russia and the world."[7] He graduated from the Moscow Agricultural Institute in 1910 with a dissertation on snails as pests. From 1911 to 1912, he worked at the Bureau for Applied Botany and at the Bureau of Mycology and Phytopathology. From 1913 to 1914 he travelled in Europe and studied plant immunity, in collaboration with the British biologist William Bateson, who helped establish the science of genetics.

From 1924 to 1935 he was the director of the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences at Leningrad. Impressed with the work of Canadian phytopathologist Margaret Newton on wheat stem rust, in 1930 he attempted to hire her to work at the institute,[8] offering a good salary and perks such as a camel caravan for her travel. She declined, but visited the institute in 1933 for three months to train 50 students in her research.

While developing his theory on the centres of origin of cultivated plants, Vavilov organized a series of botanical-agronomic expeditions, and collected seeds from every corner of the globe. In Leningrad, he created the world's largest collection of plant seeds.[9] Vavilov also formulated the law of homologous series in variation.[10] He was a member of the USSR Central Executive Committee, President of All-Union Geographical Society and a recipient of the Lenin Prize.

Vavilov encountered the young Trofim Lysenko and at the time encouraged him in his work. At the time Lysenko was not the best at growing wheat and peas, but Vavilov continued to support him and his ideas. It was not until later when he was under pressure from the Soviet State that Vavilov began to criticize the non-Mendelian concepts of Trofim Lysenko, who won the support of Joseph Stalin. As a result, Vavilov was arrested on August 6, 1940, while on an expedition to Ukraine. He was sentenced to death in July 1941. In 1942 his sentence was commuted to twenty years' imprisonment; he died in prison in 1943,[11] of starvation.[12]

The Leningrad seedbank was diligently preserved through the 28-month Siege of Leningrad. While the Soviets had ordered the evacuation of art from the Hermitage, they had not evacuated the 250,000 samples of seeds, roots, and fruits stored in what was then the world's largest seedbank. A group of scientists at the Vavilov Institute boxed up a cross section of seeds, moved them to the basement, and took shifts protecting them. Those guarding the seedbank refused to eat its contents, even though by the end of the siege in the spring of 1944, nine of them had died of starvation.[7]

In 1943, parts of Vavilov's collection, samples stored within the territories occupied by the German armies, mainly in Ukraine and Crimea, were seized by a German unit headed by Heinz Brücher. Many of the samples were transferred to the SS Institute for Plant Genetics, which had been established at the Lannach Castle near Graz, Austria.[13]

Vavilov was an atheist.[14]

After his death

In 1955, the verdict against Vavilov was posthumously set aside at a hearing of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union, undertaken as part of a de-Stalinization effort to review Stalin-era death sentences.[15] By the 1960s his reputation was publicly rehabilitated and he began to be hailed as a hero of Soviet science.[16]

Today, the N.I. Vavilov Institute of Plant Industry in St. Petersburg still maintains one of the world's largest collections of plant genetic material.[17] The Institute began as the Bureau of Applied Botany in 1894, and was reorganized in 1924 into the All-Union Research Institute of Applied Botany and New Crops, and in 1930 into the Research Institute of Plant Industry. Vavilov was the head of the institute from 1921 to 1940. In 1968 the institute was renamed after Vavilov in time for its 75th anniversary.

A minor planet, 2862 Vavilov, discovered in 1977 by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh is named after him and his brother Sergey Ivanovich Vavilov.[18] The crater Vavilov on the far side of the Moon is also named after him and his brother. The story of the researchers at the Vavilov Institute during the Siege of Leningrad was fictionalized by novelist Elise Blackwell in her 2003 novel Hunger. That novel was the inspiration for the Decemberists' song "When The War Came" in the 2006 album The Crane Wife, which also depicts the Institute during the siege and mentions Vavilov by name.

Timeline

.jpg)

- 1887 - born November 25, in Moscow.

- 1911 - graduated from the Moscow Agricultural Institute.

- 1917-1921 - professor of the agronomy department of the Saratov University.

- 1919 - theory of the immunity for plants.

- 1920 - formulation of the law of homology series in genetical mutability.

- mid 1920s - Vavilov befriends the young peasant Trofim Lysenko and begins taking him to scientific meetings

- 1921(–1940) - chairman of the applied botanics and selection section in Petrograd, which in 1924 was reorganized into the All-Union Institute of Applied Botanics and New Crops and in 1930, into the All-Union Institute of Plant Cultivation, with Vavilov being director until August, 1940.

- 1924 - Vladimir Lenin dies and is replaced by Josef Stalin - a turning point in Vavilov's life

- 1926 - Lenin Award.

- 1930–1940 - head of the genetics laboratory in Moscow, later reorganized into the Institute of Genetics of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

- 1931–1940 - President of the All-Union Geographical Society.

- Late 1930s - Lysenko, who has conceived a hatred for genetics is put in charge of all of Soviet agriculture

- 1940 - arrested for allegedly wrecking Soviet agriculture; delivered more than a hundred hours of lectures on science while in prison

- 1943 - died imprisoned and suffering from dystrophia (faulty nutrition of muscles, leading to paralysis), in the Saratov prison.

The USSR Academy of Sciences established the Vavilov Award (1965) and the Vavilov Medal (1968).

Works

- Земледельческий Афганистан. (1929) (Agricultural Afghanistan)

- Селекция как наука. (1934) (Breeding as science)

- Закон гомологических рядов в наследственной изменчивости. (1935) (The law of homology series in genetical mutability)

- Учение о происхождении культурных растений после Дарвина. (1940) (The theory of origins of cultivated plants after Darwin)

Works in English

- The Origin, Variation, Immunity and Breeding of Cultivated Plants (translated by K. Starr Chester). 1951. Chronica Botanica 13:1–366, link

- Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants (translated by Doris Löve). 1992. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-40427-4

- Five Continents (translated by Doris Löve). 1997. IPGRI, Rome; VIR, St. Petersburg ISBN 92-9043-302-7

See also

- VASKhNIL (the All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences of the Soviet Union)

- All-Russian Institute of Plant Industry

- Vavilovian mimicry

- Vavilov Center

References

- 1 2 Harland, S. C. (1954). "Nicolai Ivanovitch Vavilov. 1885-1942". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 9: 259–264. JSTOR 769210. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1954.0017.

- ↑ Shumnyĭ, V. K. (2007). "Two brilliant generalizations of Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov (for the 120th anniversary)". Genetika. 43 (11): 1447–1453. PMID 18186182.

- ↑ Zakharov, I. A. (2005). "Nikolai I Vavilov (1887–1943)". Journal of Biosciences. 30 (3): 299–301. PMID 16052067. doi:10.1007/BF02703666.

- ↑ Crow, J. F. (2001). "Plant breeding giants. Burbank, the artist; Vavilov, the scientist". Genetics. 158 (4): 1391–1395. PMC 1461760

. PMID 11514434.

. PMID 11514434. - ↑ Crow, J. F. (1993). "N. I. Vavilov, martyr to genetic truth". Genetics. 134 (1): 1–4. PMC 1205417

. PMID 8514123.

. PMID 8514123. - ↑ Cohen, B. M. (1991). "Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov: The explorer and plant collector a". Economic Botany. 45: 38–46. doi:10.1007/BF02860048.

- 1 2 Siebert, Charles. 2011. "Food Ark." National Geographic. Volume 220 (1), July 2011. Pages 122-126.

- ↑ Dale-Burnett, Lisa Lynne; Mlazagar, Brian, eds. (2006). Saskatchewan Agriculture: Lives Past and Present. Trade Books Based in Scholarship. 17. Canadian Plains Research Center. ISBN 0889771693.

- ↑ The Significance of Vavilov's Scientific Expeditions. PGR Newsletter 124. Bioversity International.

- ↑ Popov I. Yu (2002). Periodical systems in biology.

- ↑ Loren R. Graham (1993). Science in Russia and the Soviet Union: A Short History. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 0-521-28789-8.

- ↑ Gary Paul Nabhan. "How Nikolay Vavilov, the seed collector who tried to end famine, died of starvation". NPR. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ↑ Heinz Brücher and the SS botanical collecting command to Russia 1943. PGR Newsletter 129. Bioversity International.

- ↑ Peter Pringle (2008). The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov: The Story of Stalin's Persecution of One of the Great Scientists of the Twentieth Century. Simon and Schuster. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-7432-6498-3. "Despite his strict upbringing in the Orthodox Church, Vavilov had been an atheist from an early age. If he worshipped anything, it was science.

- ↑ Peter Pringle (2008). The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov. Simon & Schuster. p. 300. ISBN 0-7432-6498-3.

- ↑ James W. Atz and Robert J. Winter (1968). "Further steps in the rehabilitation of N.I. Vavilov". The Journal of Heredity. 59 (5): 274–275.

- ↑ N.I.Vavilov Research Institute of Plant Industry at www.vir.nw.ru

- ↑ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 235. ISBN 3-540-00238-3

- ↑ IPNI. Vavilov.

Further reading

- Where Our Food Comes From: Retracing Nikolay Vavilov's Quest to End Famine by Gary Paul Nabhan 2008 ISBN 978-1-59726-399-3

- Delone, N. L. (1988). "Significance of the scientific heritage of N.I. Vavilov in the development of space biology (on the centenary of his birth)". Kosmicheskaia biologiia i aviakosmicheskaia meditsina. 22 (6): 79–83. PMID 3066990.

- Vasina-Popova, E. T. (1987). "The role of N. I. Vavilov in the development of Soviet genetics and animal selection". Genetika. 23 (11): 2002–2006. PMID 3322935.

- Levina, E. S. (1987). "Not Available". Voprosy istorii estestvoznaniia i tekhniki (Institut istorii estestvoznaniia i tekhniki (Akademiia nauk SSSR)) (4): 34–43. PMID 11636235.

- Alekseev, V. P. (1987). "Not Available". Sovetskaia etnografiia / Akademiia nauk SSSR i Narodnyi komissariat prosveshcheniia RSFSR (6): 72–80. PMID 11636003.

- Raipulis, J. (1987). "Not Available". Vestis. Izvestiia. Latvijas PSR Zinatnu akademija (9): 71–76. PMID 11635329.

- "Correspondence legacy of N. I. Vavilov". Genetika. 15 (8): 1525–1526. 1979. PMID 383572.

- Berdyshev, G. D.; Savchenko, N. I.; Pomogaĭbo, V. M.; Shcherbina, D. M.; Samorodov, V. N. (1978). "Celebration of the 90th anniversary of the birth of N. I. Vavilov in the Ukraine". TSitologiia i genetika. 12 (2): 177–179. PMID 356364.

- Khuchua, K. N. (1978). "Life and career of Academician N. I. Vavilov. On the 90th anniversary of his birth". TSitologiia i genetika. 12 (2): 174–177. PMID 356363.

- Kondrashov, V. (1978). "On the 90th birthday of N. I. Vavilov". Genetika. 14 (12): 2225. PMID 369949.

- Kurlovich, B.S. WHAT IS A SPECIES? https://sites.google.com/site/biodiversityoflupins/15-objective-regularities-in-the-variability-of-chatacters/what-is-a-species

- Reznik, S. and Y. Vavilov 1997 "The Russian Scientist Nicolay Vavilov" (preface to English translation of:) Vavilov, N. I. Five Continents. IPGRI: Rome, Italy.

- Cohen, Barry Mendel 1980 Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov: His Life and Work. Ph.D.: University of Texas at Austin.

- Bakhteev, F. K.; Dickson, J. G. (1960). "To the History of Russian Science: Academician Nicholas IV an Vavilov on His 70th Anniversary (November 26, 1887-August 2, 1942)". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 35 (2): 115. doi:10.1086/403015.

- Vavilov and his Institute. A history of the world collection of plant genetic resources in Russia, Loskutov, Igor G. 1999. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy. ISBN 92-9043-412-0

- The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov: The Story of Stalin's Persecution of One of the Greatest Scientists of the Twentieth Century, by Peter Pringle. 2008. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-6498-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nikolai Vavilov. |

- Vavilov, Centers of Origin, Spread of Crops

- Vavilov Centre for Plant Industry

- Genetic Resources of Leguminous Plants in the N.I. Vavilov Institute of Plant Industry

- Theoretical base of our researches