Red-headed myzomela

| Red-headed myzomela | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male perched on a mangrove branch. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Meliphagidae |

| Genus: | Myzomela |

| Species: | M. erythrocephala |

| Binomial name | |

| Myzomela erythrocephala Gould, 1840 | |

| |

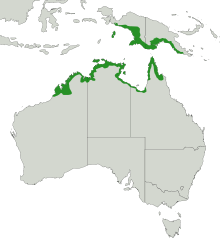

| Red-headed myzomela natural range | |

The red-headed myzomela or red-headed honeyeater (Myzomela erythrocephala) is a passerine bird of the honeyeater family, Meliphagidae, found in Australia, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea. It was described by John Gould in 1840. Two subspecies are recognised, with the nominate race M. e. erythrocephala distributed around the tropical coastline of Australia, and M. e. infuscata in New Guinea. Though widely distributed, it is not abundant within this range. While the IUCN lists the Australian population of M. e. infuscata as being near threatened, as a whole the widespread range means that its conservation is of least concern.

At 12 centimetres (4.7 in), it is a small honeyeater with a short tail and relatively long down-curved bill. It is sexually dimorphic; the male has a glossy red head and brown upperparts and paler grey-brown underparts while the female has predominantly grey-brown plumage. Its natural habitat is subtropical or tropical mangrove forests. It is very active when feeding in the tree canopy, darting from flower to flower and gleaning insects off foliage. It calls constantly as it feeds. While little has been documented on the red-headed myzomela's breeding behaviour, it is recorded as building a small cup-shaped nest in the mangroves and laying two or three oval, white eggs with small red blotches.

Taxonomy

The red-headed myzomela was described and named as Myzomela erythrocephala by John Gould in 1840,[2] from specimens collected in King Sound in northern Western Australia.[3] The genus name is derived from the Ancient Greek words myzo "to suckle" and meli "honey", and refers to the bird's nectivorous habits, while erythrocephala is from the Greek erythros "red" and a combining form of the Greek kephale "head".[4] This species was known as the red-headed honeyeater in Australia, and red-headed myzomela elsewhere,[5] the latter name being adopted as the official name by the International Ornithological Committee (IOC).[6] Other common names are mangrove red-headed honeyeater, mangrove redhead, and blood-bird.[5]

Two subspecies are recognised:[6] the nominate race M. e. erythrocephala, and M. e. infuscata, which was described by William Alexander Forbes in 1879 from a specimen collected from Hall Bay in southern New Guinea. Forbes noted there was more red on the back, and the upperparts are a lighter brown.[7] The Sumba myzomela (Myzomela dammermani) was until 2008 regarded as a subspecies of the red-headed myzomela,[6] as was the crimson-hooded myzomela (M. kuehni) which is endemic to the Indonesian island of Wetar.[8]

The red-headed myzomela is a member of the genus Myzomela which includes two other Australian species, the scarlet myzomela of eastern Australia, and the dusky myzomela of northern Australia. It belongs to the honeyeater family Meliphagidae.[9] A 2004 genetic study of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA of honeyeaters found it to be the next closest relative to a smaller group consisting of the scarlet and cardinal myzomelas, although only five of the thirty members of the genus Myzomela were analysed.[10] A 2017 genetic study using both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA suggests that the ancestor of the red-headed myzomela diverged from that of the black-breasted myzomela around 4 million years ago, however the relationships of many species within the genus is uncertain.[11] Molecular analysis has shown honeyeaters to be related to the Pardalotidae (pardalotes), Acanthizidae (Australian warblers, scrubwrens, thornbills, etc.), and the Maluridae (Australian fairy-wrens) in the large superfamily Meliphagoidea.[12] Because the red-headed myzomela occurs on many offshore islands and appears to be an effective water-crosser, it has been hypothesised that north-western Australia was the primary centre of origin for the two subspecies.[13]

Description

The red-headed myzomela is a distinctive small honeyeater with a compact body, short tail and relatively long down-curved bill. It averages 12 centimetres (4.7 in), with a wingspan of 17–19 cm (6.7–7.5 in) and a weight of 8 grams (0.28 oz). The birds exhibit sexual dimorphism, with males being slightly larger and much more brightly coloured than females.[14]

The adult male of the nominate subspecies has a dark red head, neck, and rump; the red is glossy, reflecting bright light. The rest of the upper body is a blackish-brown, and the upper breast and under-body a light brownish-grey. The red of the head is sharply demarcated against the brown plumage, giving the bird the appearance of having a red hood. The bill is black or blackish-brown, and the gape is black or yellowish. There is a distinct black loral stripe that extends to become a narrow eye ring. The iris is dark brown. The adult female's head and neck are grey-brown with a pink-red tint to the forehead and chin. The rest of the female's upper body is grey-brown with darker shades on the wings and lighter shades on the breast and underparts. The gape is yellow.[14] One study suggested a connection between the female's bill colour and breeding status, with birds that had a horn-coloured (grey) bill also having well-developed brood patches.[15] Juveniles are similar to females though with an obvious pale yellow edge to the lower mandible.[14] Initially lacking in red plumage, they begin to get red feathers on their faces after around a month of age.[8] Males keep their juvenile plumage for up to three months, and take a similar period to come into full colour.[15] M. e. infuscata is similar in appearance to the nominate race but has red extending from the rump onto the back, a darker grey belly, and is slightly larger overall.[8]

The red-headed myzomela has a range of contact calls and songs that are primarily metallic or scratchy.[16] Its song is an abrupt tchwip-tchwip-tchwip-tchwip with a slightly softer swip-swip-swip-swip contact call and a scolding charrk-charrk.[17]

The red-headed myzomela closely resembles the scarlet myzomela, though there is only a small overlap in their respective ranges, in eastern Cape York Peninsula. The latter species lives in woodlands rather than mangroves. The dusky myzomela resembles the female red-headed myzomela, but is larger and darker brown, and lacks the red markings around the bill.[18] The Sumba myzomela is similar but slightly smaller than the red-headed myzomela and has darker upper parts and a broad black pectoral band.[8]

Distribution and habitat

The nominate subspecies of the red-headed myzomela is distributed across the tropical coastlines of Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland. It inhabits coastal areas of the Kimberley and various offshore islands in Western Australia, and is similarly distributed in the Northern Territory, including Melville Island and the Sir Edward Pellew Group of Islands. It is widespread around the coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria and the Cape York Peninsula.[18] M. e. infuscata occurs at scattered sites in West Papua and in south Papua New Guinea, from the Mimika Regency in the west to the Fly River in the east, and the Aru Islands.[19] Some birds of Cape York have features intermediate between the two subspecies.[8]

Although the red-headed myzomela is widely distributed, it is not abundant within its range. The largest recorded population was 5.5 birds per hectare or 2.2 per acre at Palmerston in the Northern Territory. The peak abundance of the species in the mangroves around Darwin Harbour during the mid-dry and early wet season coincided with the production of young and the flowering of the yellow mangrove (Ceriops australis).[20]

The species' movements are poorly understood, variously described as resident, nomadic or migratory.[21] Population numbers have been reported as fluctuating in some areas with local movements possibly related to the flowering of preferred mangrove and Melaleuca food trees, and there is some indication that the birds can travel more widely.[20] A single bird was recaptured after being banded nearly five years earlier, 27 kilometres (17 mi) from the original banding site, and the species' occupation of a large number of offshore islands suggests that the red-headed myzomela is effective at crossing distances over water.[15] The maximum age recorded from banding has been 7 years 1.5 months.[22]

The red-headed myzomela mostly inhabits mangroves in monsoonal coastal areas, especially thickets of spotted mangrove (Rhizophora stylosa), smallflower bruguiera (Bruguiera parviflora) and grey mangrove (Avicennia marina) bordering islands or in river deltas, but it often also occurs in paperbark thickets fringing the mangroves such as those of cajeput (Melaleuca leucadendra).[18] It is a mangrove specialist, an adaptation that probably occurred as northern Australia became more arid and the bird populations became dependent on mangroves as other types of forest disappeared.[13] The mangroves provide nectar and insects as well as shelter and nesting sites, and they supply the majority of the species' needs for most of the year.[16] In Australia, mangrove vegetation forms a narrow discontinuous strip along thousands of kilometres of coastline, accommodating birds specialized for the habitat.[13] Eighty Mile Beach in Western Australia has no mangroves and no fringing Melaleuca forests, reducing its potential for successful colonization by nectarivores, and it marks the southern limit of the red-headed myzomela in Western Australia.[20]

The red-headed myzomela is occasionally found in swampy woodlands, casuarina woodlands and open forest, particularly those with Pandanus and paperbarks, as well as on coconut farms.[18]

Behaviour

Feeding

The red-headed myzomela is arboreal, feeding at flowers and among the outer foliage in the crowns of mangroves and other flowering trees.[17] Very active when feeding, it darts from flower to flower, probing for nectar with its long curved bill. It gleans insects from foliage and twigs, as well as sallying for flying insects. Typical invertebrates eaten include spiders and insects such as beetles, bugs, wasps and caterpillars.[16] The red-headed myzomela predominately feeds on mangrove species, and in north western Australia is the major pollinator of the rib-fruited mangrove (Bruguiera exaristata),[23] however it also feeds in paperbarks and other coastal forests and has been recorded feeding in cultivated bottlebrush and Grevillea in Darwin gardens, silver-leaf grevillea (Grevillea refracta) and green birdflower (Crotalaria cunninghamii) in northwest Western Australia. The red-headed myzomela may travel some distance from roosting areas to feed on plants in flower.[15]

Social behaviour

While the social organisation of the red-headed myzomela is relatively unknown, it is reported as being usually solitary or found in pairs, though it has been described as forming loose associations with brown honeyeaters, and other mangrove-feeding birds such as the northern fantail and yellow white-eye.[20] It is an inquisitive bird and readily responds to pishing, coming close to the caller to investigate the source of the sound and to warn off the intruder. It calls throughout the day when feeding, and males sing from exposed branches in the upper canopy of the food trees.[16]

The red-headed myzomela actively defends food trees, engaging in aggressive bill-wiping both in response to a threat and after chasing intruders from a tree. It is very antagonistic even towards its own species; the males fight by grappling in mid-air and falling close to the ground before disengaging. It constantly chases brown honeyeaters through the canopy, though it has not been observed in grappling fights with other species.[16]

Breeding

There are few scientific reports on the breeding behaviour of the red-headed myzomela, and little detail is available on the breeding season.[16] A study of populations in the western Kimberley reported that the birds hold territories through much of the dry season and then disperse.[20] The nest is built in the foliage of the mangroves, suspended by a rim from a small horizontal fork about 6–10 m (20–33 ft) above the ground or water. The nest is small and cup-shaped, and built from small pieces of bark, leaves, plant fibre and sometimes seaweed, bound together with spider web and lined with finer material. It is, on average, 5.4 cm (2.1 in) in diameter and 3.7 cm (1.5 in) deep.[16]

Measuring 16 by 12 mm (0.63 by 0.47 in), the eggs are oval, smooth and lustreless white, with small spots or blotches of red on the larger end. The clutch size is reported to be two or three eggs.[24] While there is no reliable information on incubation and feeding, it is believed that both parents are active in caring for the young.[25] A field study by Jan Lewis and colleagues found that only females bore brood patches, suggesting they alone incubated eggs.[15]

Conservation status

M. e. erythrocephala is listed as being of least concern by the IUCN,[1] because the population is widespread, however the Australian population of M. e. infuscata is listed as near threatened; it is confined to three small islands with a combined area of about 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi).[26] There is no immediate threat to the red-headed myzomela except the risk posed to low islands by rising sea levels,[26] however it has been recommended that community-based ecotourism on the tropical coast be promoted, as it could lead to monitoring of sub-populations and habitat by visiting birdwatchers and local rangers.[26]

References

- 1 2 BirdLife International (2012). "Myzomela erythrocephala". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Gould, John (1840). "Letter to Chairman of the Scientific Committee, Zoological Society of London, read before meeting of the Society of Oct. 8, 1839". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 7: 139–45 [144].

- ↑ Australian Biological Resources Study (30 August 2011). "Subspecies Myzomela (Myzomela) erythrocephala erythrocephala Gould, 1840". Australian Faunal Directory. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Australian Government. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1980) [1871]. A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged Edition). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 272, 374. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- 1 2 Gray, Jeannie; Fraser, Ian (2013). Australian Bird Names: A Complete Guide. Collingwood, Victoria: Csiro Publishing. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-643-10471-6.

- 1 2 3 Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2017). "Honeyeaters". World Bird List Version 7.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ Forbes, William Alexander (1879). "A synopsis of the Meliphaginae, genus Myzomela, with descriptions of two new species". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 256–278 [263].

- 1 2 3 4 5 Higgins 2001, p. 1164.

- ↑ Christidis, Les; Boles, Walter (2008). Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds. Collingwood, Victoria: Csiro Publishing. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-643-06511-6.

- ↑ Driskell, Amy C.; Christidis, Les (2004). "Phylogeny and evolution of the Australo-Papuan honeyeaters (Passeriformes, Meliphagidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 31 (3): 943–60. PMID 15120392. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.10.017.

- ↑ Marki, Petter Z.; Jønsson, Knud A., Irestedt, Martin; Nguyen, Jacqueline M.T.; Rahbek, Carsten; Fjeldså, Jon (2017). "Supermatrix phylogeny and biogeography of the Australasian Meliphagides radiation (Aves: Passeriformes)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 107: 516–29. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.12.021.

- ↑ Barker, F. Keith; Cibois, Alice; Schikler, Peter; Feinstein, Julie; Cracraft, Joel (2004). "Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 101 (30): 11040–45. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10111040B. PMC 503738

. PMID 15263073. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401892101

. PMID 15263073. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401892101  .

. - 1 2 3 Ford, Julian (1982). "Origin, evolution and speciation of birds specialized to mangroves in Australia". Emu. 82: 12–23. doi:10.1071/MU9820012.

- 1 2 3 Higgins 2001, p. 1158.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lewis, Jan (2010). "Notes on the moult and biology of the Red-headed Honeyeater (Myzomela erythrocephala) in the west Kimberley, Western Australia". Amytornis: Western Australian Journal of Ornithology. Perth, Western Australia: Birds Australia. 2: 15–24. ISSN 1836-3482.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Higgins 2001, p. 1161.

- 1 2 Morcombe, Michael (2003). Field Guide to Australian Birds. Archerfield, Queensland: Steve Parrish Publishing. p. 272. ISBN 1-74021-417-X.

- 1 2 3 4 Higgins 2001, p. 1159.

- ↑ Beehler, Bruce M.; Pratt, Thane K. (2016). Birds of New Guinea: Distribution, Taxonomy, and Systematics. Princeton University Press. pp. 292–93. ISBN 978-1-4008-8071-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Noske, Richard A. (1996). "Abundance, zonation and foraging ecology of birds in mangroves of Darwin Harbour, Northern Territory". Wildlife Research. 23 (4): 443–74. ISSN 1035-3712. doi:10.1071/WR9960443.

- ↑ Higgins 2001, p. 1160.

- ↑ Australian Bird & Bat Banding Scheme (ABBBS) (2017). "ABBBS Database Search: Myzomela erythrocephala (Red-headed Honeyeater)". Bird and bat banding database. Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ Noske, Richard A. (1993). "Bruguiera hainesii: another bird-pollinated mangrove?". Biotropica. 25 (4): 481–483. JSTOR 2388873. doi:10.2307/2388873.

- ↑ Beruldsen, Gordon R. (2003) [1980]. A Field Guide to Nests and Eggs of Australian Birds. Kenmore Hills, Queensland: self. p. 329. ISBN 0-646-42798-9.

- ↑ Higgins 2001, p. 1162.

- 1 2 3 Garnett, Stephen; Szabo, Judith; Dutson, Guy (2010), The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2010, Melbourne, Australia: CSIRO, ISBN 978-0-643-10368-9

Cited text

- Higgins, Peter J.; Peter, Jeffrey M.; Steele, W. K., eds. (2001). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 5: Tyrant-flycatchers to Chats. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553258-9.