Auction

An auction is a process of buying and selling goods or services by offering them up for bid, taking bids, and then selling the item to the highest bidder. The open ascending price auction is arguably the most common form of auction in use today.[1] Participants bid openly against one another, with each subsequent bid required to be higher than the previous bid.[2] An auctioneer may announce prices, bidders may call out their bids themselves (or have a proxy call out a bid on their behalf), or bids may be submitted electronically with the highest current bid publicly displayed.[2] In a Dutch auction, the auctioneer begins with a high asking price for some quantity of like items; the price is lowered until a participant is willing to accept the auctioneer's price for some quantity of the goods in the lot or until the seller's reserve price is met.[2] While auctions are most associated in the public imagination with the sale of antiques, paintings, rare collectibles and expensive wines, auctions are also used for commodities, livestock, radio spectrum and used cars. In economic theory, an auction may refer to any mechanism or set of trading rules for exchange.

History

The word "auction" is derived from the Latin augeō which means "I increase" or "I augment".[1] For most of history, auctions have been a relatively uncommon way to negotiate the exchange of goods and commodities. In practice, both haggling and sale by set-price have been significantly more common.[5] Indeed, before the seventeenth century the few auctions that were held were sporadic.[6]

Nonetheless, auctions have a long history, having been recorded as early as 500 B.C.[7] According to Herodotus, in Babylon auctions of women for marriage were held annually. The auctions began with the woman the auctioneer considered to be the most beautiful and progressed to the least. It was considered illegal to allow a daughter to be sold outside of the auction method.[6]

During the Roman Empire, following military victory, Roman soldiers would often drive a spear into the ground around which the spoils of war were left, to be auctioned off. Later slaves, often captured as the "spoils of war", were auctioned in the forum under the sign of the spear, with the proceeds of sale going towards the war effort.[6]

The Romans also used auctions to liquidate the assets of debtors whose property had been confiscated.[8] For example, Marcus Aurelius sold household furniture to pay off debts, the sales lasting for months.[9] One of the most significant historical auctions occurred in the year 193 A.D. when the entire Roman Empire was put on the auction block by the Praetorian Guard. On March 23 The Praetorian Guard first killed emperor Pertinax, then offered the empire to the highest bidder. Didius Julianus outbid everyone else for the price of 6,250 drachmas per guard, an act that initiated a brief civil war. Didius was then beheaded two months later when Septimius Severus conquered Rome.[8]

From the end of the Roman Empire to the eighteenth century auctions lost favor in Europe,[8] while they had never been widespread in Asia.[6]

Modern revival

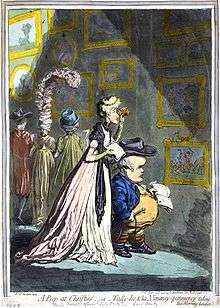

In some parts of England during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries auction by candle began to be used for the sale of goods and leaseholds.[10] In a candle auction, the end of the auction was signaled by the expiration of a candle flame, which was intended to ensure that no one could know exactly when the auction would end and make a last-second bid. Sometimes, other unpredictable processes, such as a footrace, were used in place of the expiration of a candle. This type of auction was first mentioned in 1641 in the records of the House of Lords.[11] The practice rapidly became popular, and in 1660 Samuel Pepys's diary recorded two occasions when the Admiralty sold surplus ships "by an inch of candle". Pepys also relates a hint from a highly successful bidder, who had observed that, just before expiring, a candle-wick always flares up slightly: on seeing this, he would shout his final - and winning - bid. The London Gazette began reporting on the auctioning of artwork at the coffeehouses and taverns of London in the late 17th century.

The first known auction house in the world was Stockholm Auction House, Sweden (Stockholms Auktionsverk), founded by Baron Claes Rålamb in 1674.[12][13] Sotheby's, currently the world's second-largest auction house,[12] was founded in London on 11 March 1744, when Samuel Baker presided over the disposal of "several hundred scarce and valuable" books from the library of an acquaintance. Christie's, now the world's largest auction house,[12] was founded by James Christie in 1766 in London[14] and published its first auction catalog in 1766, although newspaper advertisements of Christie's sales dating from 1759 have been found.[15]

Other early auction houses that are still in operation include Dorotheum (1707), Mallams (1788), Bonhams (1793), Phillips de Pury & Company (1796), Freeman's (1805) and Lyon & Turnbull (1826).[16]

By the end of the 18th century, auctions of art works were commonly held in taverns and coffeehouses. These auctions were held daily, and auction catalogs were printed to announce available items. In some cases these catalogs were elaborate works of art themselves, containing considerable detail about the items being auctioned. At this time, Christie's established a reputation as a leading auction house, taking advantage of London's status as the major centre of the international art trade after the French Revolution.

During the American civil war goods seized by armies were sold at auction by the Colonel of the division. Thus, some of today's auctioneers in the U.S. carry the unofficial title of "colonel".[9]

The development of the internet, however, has led to a significant rise in the use of auctions as auctioneers can solicit bids via the internet from a wide range of buyers in a much wider range of commodities than was previously practical.[5]

In 2008, the National Auctioneers Association reported that the gross revenue of the auction industry for that year was approximately $268.4 billion, with the fastest growing sectors being agricultural, machinery, and equipment auctions and residential real estate auctions.[17]

Types

Primary

There are traditionally four types of auction that are used for the allocation of a single item:

- English auction, also known as an open ascending price auction. This type of auction is arguably the most common form of auction in use today.[1] Participants bid openly against one another, with each subsequent bid required to be higher than the previous bid.[2] An auctioneer may announce prices, bidders may call out their bids themselves (or have a proxy call out a bid on their behalf), or bids may be submitted electronically with the highest current bid publicly displayed.[2] In some cases a maximum bid might be left with the auctioneer, who may bid on behalf of the bidder according to the bidder's instructions.[2] The auction ends when no participant is willing to bid further, at which point the highest bidder pays their bid.[2] Alternatively, if the seller has set a minimum sale price in advance (the 'reserve' price) and the final bid does not reach that price the item remains unsold.[2] Sometimes the auctioneer sets a minimum amount by which the next bid must exceed the current highest bid.[2] The most significant distinguishing factor of this auction type is that the current highest bid is always available to potential bidders.[2] The English auction is commonly used for selling goods, most prominently antiques and artwork,[2] but also secondhand goods and real estate.

- Dutch auction also known as an open descending price auction.[1] In the traditional Dutch auction the auctioneer begins with a high asking price for some quantity of like items; the price is lowered until a participant is willing to accept the auctioneer's price for some quantity of the goods in the lot or until the seller's reserve price is met.[2] If the first bidder does not purchase the entire lot, the auctioneer continues lowering the price until all of the items have been bid for or the reserve price is reached. Items are allocated based on bid order; the highest bidder selects their item(s) first followed by the second highest bidder, etc. In a modification, all of the winning participants pay only the last announced price for the items that they bid on.[1] The Dutch auction is named for its best known example, the Dutch tulip auctions. ("Dutch auction" is also sometimes used to describe online auctions where several identical goods are sold simultaneously to an equal number of high bidders.[18]) In addition to cut flower sales in the Netherlands, Dutch auctions have also been used for perishable commodities such as fish and tobacco.[2] The Dutch auction is not widely used.[1]

- Sealed first-price auction or blind auction,[19] also known as a first-price sealed-bid auction (FPSB). In this type of auction all bidders simultaneously submit sealed bids so that no bidder knows the bid of any other participant. The highest bidder pays the price they submitted.[1][2] This type of auction is distinct from the English auction, in that bidders can only submit one bid each. Furthermore, as bidders cannot see the bids of other participants they cannot adjust their own bids accordingly.[2] From the theoretical perspective, this kind of bid process has been argued to be strategically equivalent to the Dutch auction.[20] However, empirical evidence from laboratory experiments has shown that Dutch auctions with high clock speeds yield lower prices than FPSB auctions.[21][22] What are effectively sealed first-price auctions are commonly called tendering for procurement by companies and organisations, particularly for government contracts and auctions for mining leases.[2]

- Vickrey auction, also known as a sealed-bid second-price auction.[23] This is identical to the sealed first-price auction except that the winning bidder pays the second-highest bid rather than his or her own.[24] Vickrey auctions are extremely important in auction theory, and commonly used in automated contexts such as real-time bidding for online advertising, but rarely in non-automated contexts.[2]

Secondary

Most auction theory revolves around these four "standard" auction types. However, many other types of auctions exist, generally sharing many, including:

- Multiunit auctions sell more than one identical item at the same time, rather than having separate auctions for each. This type can be further classified as either a uniform price auction or a discriminatory price auction.

- All-pay auction is an auction in which all bidders must pay their bids regardless of whether they win. The highest bidder wins the item. All-pay auctions are primarily of academic interest, and may be used to model lobbying or bribery (bids are political contributions) or competitions such as a running race.[25]

- Auction by the candle. A type of auction, used in England for selling ships, in which the highest bid laid on the table by the time a burning candle goes out wins.

- Bidding fee auction, also known as a penny auction, often requires that each participant must pay a fixed price to place each bid, typically one penny (hence the name) higher than the current bid. When an auction's time expires, the highest bidder wins the item and must pay a final bid price.[26] Unlike in a conventional auction, the final price is typically much lower than the value of the item, but all bidders (not just the winner) will have paid for each bid placed; the winner will buy the item at a very low price (plus price of rights-to-bid used), all the losers will have paid, and the seller will typically receive significantly more than the value of the item.[27]

- Buyout auction is an auction with an additional set price (the 'buyout' price) that any bidder can accept at any time during the auction, thereby immediately ending the auction and winning the item.[28] If no bidder chooses to utilize the buyout option before the end of bidding the highest bidder wins and pays their bid.[28] Buyout options can be either temporary or permanent.[28] In a temporary-buyout auction the option to buy out the auction is not available after the first bid is placed.[28] In a permanent-buyout auction the buyout option remains available throughout the entire auction until the close of bidding.[28] The buyout price can either remain the same throughout the entire auction, or vary throughout according to rules or simply as decided by the seller.[28]

- Combinatorial auction is any auction for the simultaneous sale of more than one item where bidders can place bids on an "all-or-nothing" basis on "packages" rather than just individual items. That is, a bidder can specify that he or she will pay for items A and B, but only if he or she gets both.[29] In combinatorial auctions, determining the winning bidder(s) can be a complex process where even the bidder with the highest individual bid is not guaranteed to win.[29] For example, in an auction with four items (W, X, Y and Z), if Bidder A offers $50 for items W & Y, Bidder B offers $30 for items W & X, Bidder C offers $5 for items X & Z and Bidder D offers $30 for items Y & Z, the winners will be Bidders B & D while Bidder A misses out because the combined bids of Bidders B & D is higher ($60) than for Bidders A and C ($55).

- Generalized second-price auction and Generalized first-price auction

- Unique bid auctions

- Many homogenous item auctions, e.g., spectrum auctions

- Japanese auction is a variation of the English auction. When the bidding starts no new bidders can join, and each bidder must continue to bid each round or drop out. It has similarities to the ante in Poker.[30]

- Lloyd's syndicate auction.[31]

- Mystery auction is a type of auction where bidders bid for boxes or envelopes containing unspecified or underspecified items, usually on the hope that the items will be humorous, interesting, or valuable.[32][33] In the early days of eBay's popularity, sellers began promoting boxes or packages of random and usually low-value items not worth selling by themselves.[34]

- No-reserve auction (NR), also known as an absolute auction, is an auction in which the item for sale will be sold regardless of price.[35][36] From the seller's perspective, advertising an auction as having no reserve price can be desirable because it potentially attracts a greater number of bidders due to the possibility of a bargain.[35] If more bidders attend the auction, a higher price might ultimately be achieved because of heightened competition from bidders.[36] This contrasts with a reserve auction, where the item for sale may not be sold if the final bid is not high enough to satisfy the seller. In practice, an auction advertised as "absolute" or "no-reserve" may nonetheless still not sell to the highest bidder on the day, for example, if the seller withdraws the item from the auction or extends the auction period indefinitely,[37] although these practices may be restricted by law in some jurisdictions or under the terms of sale available from the auctioneer.

- Reserve auction is an auction where the item for sale may not be sold if the final bid is not high enough to satisfy the seller; that is, the seller reserves the right to accept or reject the highest bid.[36] In these cases a set 'reserve' price known to the auctioneer, but not necessarily to the bidders, may have been set, below which the item may not be sold.[35] The reserve price may be fixed or discretionary. In the latter case, the decision to accept a bid is deferred to the auctioneer, who may accept a bid that is marginally below it. A reserve auction is safer for the seller than a no-reserve auction as they are not required to accept a low bid, but this could result in a lower final price if less interest is generated in the sale.[36]

- Reverse auction is a type of auction in which the roles of the buyer and the seller are reversed, with the primary objective to drive purchase prices downward.[38] While ordinary auctions provide suppliers the opportunity to find the best price among interested buyers, reverse auctions give buyers a chance to find the lowest-price supplier. During a reverse auction, suppliers may submit multiple offers, usually as a response to competing suppliers’ offers, bidding down the price of a good or service to the lowest price they are willing to receive. By revealing the competing bids in real time to every participating supplier, reverse auctions promote “information transparency”. This, coupled with the dynamic bidding process, improves the chances of reaching the fair market value of the item.[39] The reverse auction is widely used by corporations, state and local Governments, and other organizations. The uses are vast and include services as well as goods.[40]

- Senior auction is a variation on the all-pay auction, and has a defined loser in addition to the winner. The top two bidders must pay their full final bid amounts, and only the highest wins the auction. The intent is to make the high bidders bid above their upper limits. In the final rounds of bidding, when the current losing party has hit their maximum bid, they are encouraged to bid over their maximum (seen as a small loss) to avoid losing their maximum bid with no return (a very large loss).[41]

- Silent auction is a variant of the English auction in which bids are written on a sheet of paper. At the predetermined end of the auction, the highest listed bidder wins the item.[42] This auction is often used in charity events, with many items auctioned simultaneously and "closed" at a common finish time.[42][43] The auction is "silent" in that there is no auctioneer selling individual items,[42] the bidders writing their bids on a bidding sheet often left on a table near the item.[44] At charity auctions, bid sheets usually have a fixed starting amount, predetermined bid increments, and a "guaranteed bid" amount which works the same as a "buy now" amount. Other variations of this type of auction may include sealed bids.[42] The highest bidder pays the price he or she submitted.[42]

- Top-up auction is a variation on the all-pay auction, primarily used for charity events. Losing bidders must pay the difference between their bid and the next lowest bid. The winning bidder pays the amount bid for the item, without top-up.

- Walrasian auction or Walrasian tâtonnement is an auction in which the auctioneer takes bids from both buyers and sellers in a market of multiple goods.[45] The auctioneer progressively either raises or drops the current proposed price depending on the bids of both buyers and sellers, the auction concluding when supply and demand exactly balance.[46] As a high price tends to dampen demand while a low price tends to increase demand, in theory there is a particular price somewhere in the middle where supply and demand will match.[45]

- Amsterdam auctions, a type of premium auction which begins as an English auction. Once only two bidders remain, each submits a sealed bid. The higher bidder wins, paying either the first or second price. Both finalists receive a premium: a proportion of the excess of the second price over the third price (at which English auction ended).[47]

- Other auctions: Other auction types also exist, such as Simultaneous Ascending Auction[48] Anglo-Dutch auction,[49] Private value auction,[50] Common value auction

Genres

The range of auctions that take place is extremely wide and one can buy almost anything, from a house to an endowment policy and everything in-between. Some of the recent developments have been the use of the Internet both as a means of disseminating information about various auctions and as a vehicle for hosting auctions themselves.

Here is a short description of the most common types of auction.

- Government, bankruptcy and general auctions are amongst the most common auctions to be found today. A government auction is simply an auction held on behalf of a government body generally at a general sale. Here one may find a vast range of materials that have to be sold by various government bodies, for example: HM Customs & Excise, the Official Receiver, the Ministry of Defence, local councils and authorities, liquidators, as well as material put up for auction by companies and members of the public. Also in this group you will find auctions ordered by executors who are entering the assets of individuals who have perhaps died in testate (those who have died without leaving a will), or in debt. One of the most interesting bodies to look out for at auction is HM Customs & Excise who may be entering at auction various items seized from smugglers, fraudsters and racketeers.

- Motor vehicle and car auctions – Here one can buy anything from an accident-damaged car to a brand new top-of-the-range model; from a run-of-the-mill family saloon to a rare collector's item.

- Police auctions are generally held at general auctions although some forces use online sites including eBay to dispose of lost and found and seized goods.

- Land and property auctions – Here one can buy anything from an ancient castle to a brand new commercial premises.

- Antiques and collectibles auctions hold the opportunity for viewing a huge array of items.

- Internet auctions – With a potential audience of millions the Internet is the most exciting part of the auction world at the moment. Led by sites in the United States but closely followed by UK auction houses, specialist Internet auctions are springing up all over the place, selling everything from antiques and collectibles to holidays, air travel, brand new computers, and household equipment.

- Titles – One can buy a manorial title at auction. Every year several of these specialist auctions take place. However, it is important to note that manorial titles are not the same thing as peerages, and have been described as "meaningless" in the modern world.[51]

- Insurance policies – Auctions are held for second-hand endowment policies. The attraction is that someone else has already paid substantially to set up the policy in the first place, and one will be able (with the help of a financial calculator) to calculate its real worth and decide whether it is worth taking on.

- On-site auctions – Sometimes when the stock or assets of a company are simply too vast or too bulky for an auction house to transport to their own premises and store, they will hold an auction within the confines of the bankrupt company itself. Bidders could find themselves bidding for items which are still plugged in, and the great advantage of these auctions taking place on the premises is that they have the opportunity to view the goods as they were being used, and may be able to try them out. Bidders can also avoid the possibility of goods being damaged whilst they are being removed as they can do it or at least supervise the activity.

- Private treaty sales – Occasionally, when looking at an auction catalogue some of the items have been withdrawn. Usually these goods have been sold by 'private treaty'. This means that the goods have already been sold off, usually to a trader or dealer on a private, behind-the-scenes basis before they have had a chance to be offered at the auction sale. These goods are rarely in single lots – photocopiers or fax machines would generally be sold in bulk lots.

- Charity auctions - Used by nonprofits, higher education, and religious institutions as a method to raise funds for a specific mission or cause both through the act of bidding itself, and by encouraging participants to support the cause and make personal donations.[52] Often, these auctions are linked with another charity event like a benefit concert.[53]

Time requirements

Each type of auction has its specific qualities such as pricing accuracy and time required for preparing and conducting the auction. The number of simultaneous bidders is of critical importance. Open bidding during an extended period of time with many bidders will result in a final bid that is very close to the true market value. Where there are few bidders and each bidder is allowed only one bid, time is saved, but the winning bid may not reflect the true market value with any degree of accuracy. Of special interest and importance during the actual auction is the time elapsed from the moment that the first bid is revealed to the moment that the final (winning) bid has become a binding agreement.

Characteristics

Auctions can differ in the number of participants:

- In a supply (or reverse) auction, m sellers offer a good that a buyer requests

- In a demand auction, n buyers bid for a good being sold

- In a double auction n buyers bid to buy goods from m sellers

Prices are bid by buyers and asked (or offered) by sellers. Auctions may also differ by the procedure for bidding (or asking, as the case may be):

- In an open auction participants may repeatedly bid and are aware of each other's previous bids.

- In a closed auction buyers and/or sellers submit sealed bids

Auctions may differ as to the price at which the item is sold, whether the first (best) price, the second price, the first unique price or some other. Auctions may set a reservation price which is the least/maximum acceptable price for which a good may be sold/bought.

Without modification, auction generally refers to an open, demand auction, with or without a reservation price (or reserve), with the item sold to the highest bidder.

Supply auction |

Demand auction |

Double auction |

Common uses

Auctions are publicly and privately seen in several contexts and almost anything can be sold at auction. Some typical auction arenas include the following:

- The antique business, where besides being an opportunity for trade they also serve as social occasions and entertainment

- In the sale of collectibles such as stamps, coins, vintage toys & trains, classic cars, fine art[54] and luxury real estate

- The wine auction business, where serious collectors can gain access to rare bottles and mature vintages, not typically available through retail channels

- In the sale of all types of real property including residential and commercial real estate, farms, vacant lots and land; this is the method used on tax sales.

- For the sale of consumer second-hand goods of all kinds, particularly farm (equipment) and house clearances and online auctions.

- Sale of industrial machinery, both surplus or through insolvency.

- In commodities auctions, like the fish wholesale auctions

- In livestock auctions where sheep, cattle, pigs and other livestock are sold. Sometimes very large numbers of stock are auctioned, such as the regular sales of 50,000 or more sheep during a day in New South Wales.[55]

- In wool auctions where international agents purchase lots of wool[56]

- Thoroughbred horses, where yearling horses and other bloodstock are auctioned.[57]

- In legal contexts where forced auctions occur, as when one's farm or house is sold at auction on the courthouse steps. (Property seized for non-payment of property taxes, or under foreclosure, is sold in this manner.)

- Travel tickets. One example is SJ AB in Sweden auctioning surplus at Tradera (Swedish eBay).

- Holidays. A variety of holidays are available for sale online particularly via eBay. Vacation rentals appear to be most common. Many holiday auction websites have launched but failed.[58]

- Self storage units. In certain jurisdictions, if a storage facility's tenant fails to pay his/her rent, the contents of his/her locker(s) may be sold at a public auction. Several television shows focus on such auctions, including Storage Wars and Auction Hunters.

Although less publicly visible, the most economically important auctions are the commodities auctions in which the bidders are businesses even up to corporation level. Examples of this type of auction include:

- Sales of businesses

- Spectrum auctions, in which companies purchase licenses to use portions of the electromagnetic spectrum for communications (e.g., mobile phone networks)

- Private electronic markets using combinatorial auction techniques to continuously sell commodities (coal, iron ore, grain, water...) to a pre-qualified group of buyers (based on price and non-price factors)

- Timber auctions, in which companies purchase licenses to log on government land

- Timber allocation auctions, in which companies purchase timber directly from the government Forest Auctions

- Electricity auctions, in which large-scale generators and consumers of electricity bid on generating contracts

- Environmental auctions, in which companies bid for licenses to avoid being required to decrease their environmental impact. These include auctions in emissions trading schemes.

- Debt auctions, in which governments sell debt instruments, such as bonds, to investors. The auction is usually sealed and the uniform price paid by the investors is typically the best non-winning bid. In most cases, investors can also place so called non-competitive bids, which indicates an interest to purchase the debt instrument at the resulting price, whatever it may be

- Auto auctions, in which car dealers purchase used vehicles to retail to the public.

- Produce auctions, in which produce growers have a link to localized wholesale buyers (buyers who are interested in acquiring large quantities of locally grown produce).[59]

Bidding strategy

Katehakis and Puranam provided the first model[61] for the problem of optimal bidding for a firm that in each period procures items to meet a random demand by participating in a finite sequence of auctions. In this model an item valuation derives from the sale of the acquired items via their demand distribution, sale price, acquisition cost, salvage value and lost sales. They established monotonicity properties for the value function and the optimal dynamic bid policy. They also provided a model[62] for the case in which the buyer must acquire a fixed number of items either at a fixed buy-it-now price in the open market or by participating in a sequence of auctions. The objective of the buyer is to minimize his expected total cost for acquiring the fixed number of items.

Bid shading

Bid shading is placing a bid which is below the bidder's actual value for the item. Such a strategy risks losing the auction, but has the possibility of winning at a low price. Bid shading can also be a strategy to avoid the Winner's curse.

Chandelier or rafter bidding

This is the practice, especially by high-end art auctioneers,[63] of raising false bids at crucial times in the bidding in order to create the appearance of greater demand or to extend bidding momentum for a work on offer. To call out these nonexistent bids auctioneers might fix their gaze at a point in the auction room that is difficult for the audience to pin down.[64] The practice is frowned upon in the industry.[64] In the United States, chandelier bidding is not illegal. In fact, an auctioneer may bid up the price of an item to the reserve price, which is an unstated amount the consignor will not sell the item for. However, the auction house is required to disclose this information.

In the United Kingdom this practice is legal on property auctions up to but not including the reserve price, and is also known as off-the-wall bidding.[65]

Collusion

Whenever bidders at an auction are aware of the identity of the other bidders there is a risk that they will form a "ring" or "pool" and thus manipulate the auction result, a practice known as collusion. By agreeing to bid only against outsiders, never against members of the "ring", competition becomes weaker, which may dramatically affect the final price level. After the end of the official auction an unofficial auction may take place among the "ring" members. The difference in price between the two auctions could then be split among the members. This form of a ring was used as a central plot device in the opening episode of the 1979 British television series The House of Caradus, 'For Love or Money', uncovered by Helena Caradus on her return from Paris.

A ring can also be used to increase the price of an auction lot, in which the owner of the object being auctioned may increase competition by taking part in the bidding him or herself, but drop out of the bidding just before the final bid. In Britain and many other countries, rings and other forms of bidding on one's own object are illegal. This form of a ring was used as a central plot device in an episode of the British television series Lovejoy (series 4, episode 3), in which the price of a watercolour by the (fictional) Jessie Webb is inflated so that others by the same artist could be sold for more than their purchase price.

In an English auction, a dummy bid is a bid made by a dummy bidder acting in collusion with the auctioneer or vendor, designed to deceive genuine bidders into paying more. In a first-price auction, a dummy bid is an unfavourable bid designed so as not to become the winning bid. (The bidder does not want to win this auction, but he or she wants to make sure to be invited to the next auction).

In Australia, a dummy bid (shill, schill) is a criminal offence, but a vendor bid or a co-owner bid below the reserve price is permitted, if clearly declared as such by the auctioneer. These are all official legal terms in Australia, but may have other meanings elsewhere. A co-owner is one of two or several owners (who disagree among themselves).

In Sweden and many other countries there are no legal restrictions, but it will severely hurt the reputation of an auction house that knowingly permits any other bids except genuine bids. If the reserve is not reached this should be clearly declared.

In South Africa auctioneers can use their staff or any bidder to raise the price as long as its disclosed before the auction sale. The Auction Alliance[66] controversy focused on vendor bidding and it was proven to be legal and acceptable in terms of the South African consumer laws.

Suggested opening bid (SOB)

There will usually be an estimate of what price the lot will fetch. In an ascending open auction it is considered important to get at least a 50-percent increase in the bids from start to finish. To accomplish this, the auctioneer must start the auction by announcing a suggested opening bid (SOB) that is low enough to be immediately accepted by one of the bidders. Once there is an opening bid, there will quickly be several other, higher bids submitted. Experienced auctioneers will often select an SOB that is about 45 percent of the (lowest) estimate. Thus there is a certain margin of safety to ensure that there will indeed be a lively auction with many bids submitted. Several observations indicate that the lower the SOB, the higher the final winning bid. This is due to the increase in the number of bidders attracted by the low SOB.

A chi-squared distribution shows many low bids but few high bids. Bids "show up together"; without several low bids there will not be any high bids.

Another approach to choosing an SOB: The auctioneer may achieve good success by asking the expected final sales price for the item, as this method suggests to the potential buyers the item's particular value. For instance, say an auctioneer is about to sell a $1,000 car at a sale. Instead of asking $100, hoping to entice wide interest (for who wouldn't want a $1,000 car for $100?), the auctioneer may suggest an opening bid of $1,000; although the first bidder may begin bidding at a mere $100, the final bid may more likely approach $1,000.

Terminology

- Appraisal – an estimate of an item's worth, usually performed by an expert in that particular field.[67]

- Auction block - a raised platform on which the auctioneer shows the items to be auctioned; can also be slang for the auction itself.

- Auction chant - a rhythmic repetition of numbers and "filler words" spoken by an auctioneer in the process of conducting an auction.

- Auction fever - an emotional state elicited in the course of one or more auctions that causes a bidder to deviate from an initially chosen bidding strategy.[68][69]

- Auction house - the company operating the auction (i.e., establishing the date and time of the auction, the auction rules, determining which item(s) are to be included in the auction, registering bidders, taking payments, and delivering the goods to the winning bidders).

- Auctioneer - the person conducting the actual auction. They announce the rules of the auction and the item(s) being auctioned, call and acknowledging bids made, and announce the winner. They generally will call the auction using auction chant.

- The auctioneer may operate his/her own auction house (and thus perform the duties of both auctioneer and auction house), and/or work for another house.

- Auctioneers are frequently regulated by governmental entities, and in those jurisdictions must meet certain criteria to be licensed (be of a certain age, have no disqualifying criminal record, attend auction school, pass an examination, and pay a licensing fee).

- Auctioneers may or may not (depending on the laws of the jurisdiction and/or the policies of the auction house) bid for their own account, or if they do must disclose this to bidders at the auction; similar rules may apply for employees of the auctioneer or the auction house.

- Bidding - the act of participating in an auction by offering to purchase an item for sale.

- Buyer's premium – a fee paid by the buyer to the auction house; it is typically calculated as a percentage of the winning bid and added on it. Depending on the jurisdiction the buyer's premium, in addition to the sales price, may be subject to VAT or sales tax.

- Buyout price – A price that, if accepted by a bidder, immediately ends the auction and awards the item to him/her (an example is eBay's BuyItNow feature).

- "Choice" - a form of bidding whereby a number of identical or similar items are bid at a single price for each item.[70]

- "Choice" differs from "lot" in that the winning bidder must take at least one of the items, and can take more than one (up to and including all of them) but is not required to do so.

- If the bidder takes more than one item, the price paid is "times the money" (see below).

- Items not selected by the winning bidder may then be reauctioned to other bidders.

- Example: An auction has five bath fragrance gift baskets where bidding is "choice", and the hammer price is USD $5. The winner must choose at least one basket, but can choose two, three, four, or all five baskets. If the winner chooses to take three baskets, s/he must pay $15 (three baskets @ $5 each). The other two baskets may then be reauctioned.

- Clearance rate – The percentage of items that sell over the course of the auction.

- Commission – a fee paid by a consignor/seller to the auction house; it is typically calculated as a percentage of the winning bid and deducted from the gross proceeds due to the consignor/seller.

- Consignee and consignor - as pertaining to auctions, the consignor (also called the seller, and in some contexts the vendor) is the person owning the item to be auctioned or the owner's representative,[64] while the consignee is the auction house. The consignor maintains title until such time that an item is purchased by a bidder and the bidder pays the auction house.

- Dummy bid (a/k/a "ghost bid") - a false bid, made by someone in collusion with the seller or auctioneer, designed to create a sense of increased interest in the item (and, thus, increased bids).

- Dynamic closing - a mechanism used to prevent auction sniping, by which the closing time is extended for a small period to allow other bidders to increase their bids.

- eBidding – electronic bidding, whereby a person may make a bid without being physically present at an auction (or where the entire auction is taking place on the Internet).

- Earnest money deposit (a/k/a "caution money deposit" or "registration deposit") – a payment that must be made by prospective bidders ahead of time in order to participate in an auction.

- The purpose of this deposit is to deter non-serious bidders from attending the auction; by requiring the deposit, only bidders with a genuine interest in the item(s) being sold will participate.

- This type of deposit is most often used in auctions involving high-value goods (such as real estate).

- The winning bidder has his/her earnest money applied toward the final selling price; the non-winners have theirs refunded to them.

- Escrow – an arrangement in which the winning bidder pays the amount of his/her bid to a third party, who in turn releases the funds to the seller under agreed-upon terms.

- Hammer price – the nominal price at which a lot is sold; the winner is responsible for paying any additional fees and taxes on top of this amount.[71]

- Increment – a minimum amount by which a new bid must exceed the previous bid. An auctioneer may decrease the increment when it appears that bidding on an item may stop, so as to get a higher hammer price. Alternatively, a participant may offer a bid at a smaller increment, which the auctioneer has the discretion to accept or reject.

- Lot – either a single item being sold, or a group of items[64] (which may or may not be similar or identical, such as a "job lot" of manufactured goods) that are bid on as one unit.

- If the lot is for a group of items, the price paid is for the entire lot and the winning bidder must take all the items sold.

- Variants on a group lot bid include "choice" and "times the money" (see definitions for each).

- Example: An auction has five bath fragrance gift baskets where bidding is "lot", and the hammer price is USD $5. The winner must pay $5 (as the price is for the whole lot) and must take all five baskets.

- Minimum bid – The smallest opening bid that will be accepted.

- A minimum bid can be as little as USD$0.01 (one cent) depending on the auction.

- If no one bids at the initial minimum bid, the auctioneer may lower the minimum bid so as to create interest in the item.

- The minimum bid differs from a reserve price (see definition), in that the auctioneer sets the minimum bid, while the seller sets the reserve price (if desired).

- "New money" - a new bidder, joining bidding for an item after others have bid against each other.

- No reserve auction (a/k/a "absolute auction") – an auction in which there is no minimum acceptable price; so long as the winning bid is at least the minimum bid, the seller must honor the sale.

- Outbid (also spelled "out-bid" or "out bid") – to bid higher than another bidder.

- Opening bid – the first bid placed on a particular lot. The opening bid must be at least the minimum bid, but may be higher (e.g., a bidder may shout out a considerably larger bid than minimum, to discourage other bidders from bidding).

- Paddle - a numbered instrument used to place a bid[64]

- Protecting a Market - when a dealer places a bid on behalf of an artist he or she represents or otherwise has a financial interest in ensuring a high price. Artists represented by major galleries typically expect this kind of protection from their dealers.[64]

- Proxy bid (a/k/a "absentee bid") – a bid placed by an authorized representative of a bidder who is not physically present at the auction.

- Proxy bids are common in auctions of high-end items, such as art sales (where the proxy represents either a private bidder who does not want to be disclosed to the public, or a museum bidding on a particular item for its collection).

- If the proxy is outbid on an item during the auction, the proxy (depending on the instructions of the bidder) may either increase the bid (up to a set amount established by the bidder) or be required to drop out of the bidding for that item.

- A proxy may also be limited by the bidder in the total amount to spend on items in a multi-item auction.

- Relisting - re-selling an item that has already been sold at auction, but where the buyer did not take possession of the item (for example, in a real estate auction, the buyer did not provide payment by the closing date).

- Reserve price – A minimum acceptable price established by the seller prior to the auction, which may or may not be disclosed to the bidders.[64]

- If the winning bid is below the reserve price, the seller has the right to reject the bid and withdraw the item(s) being auctioned.

- The reserve price differs from a minimum bid (see definition), in that the seller sets the reserve price (if desired), while the auctioneer sets the minimum bid.

- Sealed bid - a submitted bid whose value is unknown to competitors.

- Sniping – the act of placing a bid just before the end of a timed auction, thus giving other bidders no time to enter new bids.

- Specialist - on-staff trained professionals who put together the auction[64]

- The "three Ds" death, divorce, or debt - sometimes a reason for an item to be sold at an auction[64]

- "Times the money" - a form of bidding similar to "choice", whereby the bid price is per item, but where the winning bidder must take all of the items offered for sale.[71]

- The price paid in a "times the money" bid is the bid price multiplied by the number of items, plus buyer's premium and any applicable taxes.

- "Times the money" differs from "lot" in that the price is per item, not one price for all of the items as a group.

- Example: An auction has five bath fragrance gift baskets where bidding is "times the money", and the hammer price is USD $5. The winner must pay $25 (five baskets @ $5 each) and must take all five baskets.

- Vendor bid - a bid by the person selling the item. The bid is sometimes a dummy bid (see definition) but not always.

- White Glove Sale - an auction in which every single lot is sold[64]

JEL classification

The Journal of Economic Literature (JEL) classification code for auctions is D44.[72]

See also

- Types of auction:

- Other topics:

- Auction chant

- Auction Network

- Auction school

- Auction theory

- Dollar auction

- Foreclosure

- Game theory

- Monopoly (game), a game in which auctions are sometimes used

- Online auction business model

- Online auction tools

- Online travel auction

- Silent trade

- Tendering

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Krishna, 2002: p2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 McAfee, Dinesh Satam; McMillan, Dinesh (1987), "Auctions and Bidding" (PDF), Journal of Economic Literature, American Economic Association (published June 1987), 25 (2), pp. 699–738, JSTOR 2726107, retrieved 2008-06-25

- ↑ Sotheby's (2007-06-07), Sotheby's Sets a New World Record for Sculpture at Auction (PDF), retrieved 2008-06-20

- ↑ New York Times (2008-01-10), "Artemis and Stag at Met Museum", The New York Times, retrieved 2008-06-20

- 1 2 "The Heyday of the Auction", The Economist, 352 (8129): 67–68, 1999-07-24, ISSN 0013-0613

- 1 2 3 4 Shubik, 2004: p214

- ↑ Krishna, 2002: p1

- 1 2 3 Shubik, 2004: p215

- 1 2 Doyle, Robert A.; Baska, Steve (November 2002), "History of Auctions: From ancient Rome to today's high-tech auctions", Auctioneer, archived from the original on 2008-05-17, retrieved 2008-06-22

- ↑ R.W. Patten. "Tatworth Candle Auction." Folklore 81, No. 2 (Summer 1970), 132-135

- ↑ William S. Walsh A Handy Book Of Curious Information Comprising Strange Happenings in the Life of Men and Animals, Odd Statistics, Extraordinary Phenomena and Out of the Way Facts Concerning the Wonderlands of the Earth. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1913. 63-64.

- 1 2 3 Varoli, John (2007-10-02), "Swedish Auction House to Sell 8 Million Euros of Russian Art", Bloomberg.com News, Moscow: Bloomberg Finance L.P., retrieved 2008-06-21

- ↑ About the company, Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholms Auktionsverk, archived from the original on May 22, 2008, retrieved 2008-06-21

- ↑ "Christies.com – About Us". Retrieved 3 December 2008.

James Christie conducted the first sale in London on 5 December 1766.

- ↑ Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser (London, England), Saturday, 25 September 1762; Issue 10460

- ↑ Stoica, Michael (August 2007), The Business of Art, retrieved 2008-06-21

- ↑ "Auction Industry Sees Growth in Real Estate". Realtor Mag. NAR. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ↑ eBay, Selling Multiple Items in a Listing (Dutch Auction), retrieved 2009-01-09

- ↑ Shor, Mikhael, "blind auction" Dictionary of Game Theory Terms Archived [Date error] (5), at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Krishna, 2002: p13

- ↑ Katok, E.; Kwasnica, A.M. (2008). "Time is money: The effect of clock speed on seller's revenue in Dutch auctions". Experimental Economics. 11 (4): 344–357. doi:10.1007/s10683-007-9169-x.

- ↑ Adam, M. T. P.; Krämer, J.; Weinhardt, C. (2012). "Excitement up! Price down! Measuring emotions in Dutch auctions". International Journal of Electronic Commerce. 11 (4): 7–39. doi:10.2753/JEC1086-4415170201.

- ↑ Krishna, 2002: p9

- ↑ Krishna, 2002: p3

- ↑ Milgrom, 2004: p119

- ↑ Nasri, Grace (2011-04-07). "The Seduction of the Penny Auction". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ↑ "QuiBids.com Reviews – Legit or Scam?". Reviewopedia.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gallien, Jérémie; Gupta, Shobhit (May 2007), "Temporary and Permanent Buyout Prices in Online Auctions", Management Science, INFORMS, 53 (5): 814–833, ISSN 1526-5501, doi:10.1287/mnsc.1060.0650

- 1 2 Pekec, Aleksandar; Rothkopf, Michael H. (November 2003), "Combinatorial auction design", Management Science, INFORMS, 49 (11): 1485–1503, ISSN 1526-5501, doi:10.1287/mnsc.49.11.1485.20585

- ↑ "Auction Types & Terms". Auctusdev.com. Retrieved 2012-12-26.

- ↑ https://wayback.archive.org/web/*/http://www.lloyds.com/Lloyds_Market/Capacity/Capacity_auctions/Auction_process.htm

- ↑ Ralph Brody; Marcie Goodman, Fund-raising events: strategies and programs for success, Human Sciences Press, 1988, ISBN 0898853621

- ↑ Harold W. Donahue, The Toastmaster's Manual, Kessinger Publishing, 2005, ISBN 1419156365

- ↑ Julia L. Wilkinson, The Ebay Price Guide: What Sells for What, No Starch Press, 2006, ISBN 1593270550

- 1 2 3 Fisher, Steven (2006), The Real Estate Investor's Handbook: The Complete Guide for the Individual Investor, Ocala, Florida: Atlantic Publishing Company, pp. 89–90, ISBN 0-910627-69-X

- 1 2 3 4 Good, Steven L.; Lynn, Paul A. (January 2007), "The eBay Effect", Commercial Investment Real Estate, CCIM Institute, retrieved 2009-06-25

- ↑ Leichman, Laurence (1996), 90% off! real estate, Ocala, Florida: Leichman Assoc Pubns, pp. 78–79, ISBN 0-9636867-7-1

- ↑ Schoenherr, Tobias; Mabert, Vincent A. (September–October 2007), "Online reverse auctions: Common myths versus evolving reality", Business Horizons, Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, 50 (5): 373–384, doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2007.03.003

- ↑ Moshe, Shalev; Stee, Asbjornsen (Fall 2010). "Electronic reverse auctions and the public sector - factors of success". J. Public Procurement. 10 (3): 428–452. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ↑ "Free Online Reverse Auctions". Oltiby.com. Retrieved 2012-12-26.

- ↑ Ab Hugh, Dafydd. A Balance of Power. Star Trek Press, 1995

- 1 2 3 4 5 Isaac, R. Mark; Schnier, Kurt (October 2005), "Silent auctions in the field and in the laboratory", Economic Inquiry, Oxford, United Kingdom: Western Economic Association International, 43 (4): 715–733, ISSN 0095-2583, doi:10.1093/ei/cbi050

- ↑ "Best Silent Auction Closing Time For Your Fundraiser". Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ↑ Milgrom, 2004: p268

- 1 2 Milgrom, 2004: p267

- ↑ Milgrom, 2004: pp. 267-268

- ↑ "The Amsterdam Auction" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- ↑ Peter, Cramton (2006), "Simultaneous Ascending Auctions", in Cramton, Peter; Shoham, Yoav; Steinberg, Richard, Combinatorial Auctions, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-03342-8

- ↑ https://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~dquint/econ805%202007/econ%20805%20lecture%2012.pdf

- ↑ Wikiversity:Economic Classroom Experiments/Private Value Auctions

- ↑ Harrison, David (16 May 2010). "The Lord and Lady Delusions of Grandeur". The Telegraph. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ↑ "GiveSmart: How to Turn Bidders Into Donors". GiveSmart. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ↑ "Charity Auctions: The Ultimate Guide". Double the Donation. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ↑ Canadian Museum of Civilization and Canada Postal Museum – Auction of Fine Art and Stamps

- ↑ The Land Newspaper, Prime sheep, Rural Press, 13 August 2009.

- ↑ Combined factors hit wool auctions hard

- ↑ William Inglis & Son Limited

- ↑ d'Arcy, Susan (2010-01-24). "Bag a holiday bargain in an online auction". The Times. London.

- ↑ Gray, T. W. (2005). "Local-based, alternative-marketing strategy could help save more small farms". Rural Cooperatives. 72: 20–3.

- ↑ Melikian, Souren (2005-07-26), Chinese Jar Sets Record for Asian Art, The New York Times, retrieved 2008-06-19

- ↑ Katehakis, Michael; Puranam, Kartikeya S. (July 2012), "On optimal bidding in sequential procurement auctions", Operations Research Letters, INFORMS, 40 (4): 244–249, doi:10.1016/j.orl.2012.03.012

- ↑ Katehakis, Michael; Puranam, Kartikeya S. (October 2012), "On bidding for a fixed number of items in a sequence of auctions", European Journal of Operational Research, ELSEVIER, 222 (1): 76–84, doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2012.03.050

- ↑ Grant, Daniel. "Legislators Seek to Stop 'Chandelier Bidding' at Auction". ArtNews. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Andrew M. Goldstein. "A Beginner's Guide to Art Auctions", artspace.com, 8 November 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Name:. "What is bidding off the wall? | UK Property Auctions". Ukauctions.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-12-26.

- ↑ Rael Levitt

- ↑ "Wine Valuation, Price Guides, Auction results Australia". Wickman's Fine Wine Auctions.

- ↑ Adam, M.T.P.; Krämer, J.; Jähnig, C.; Seifert, S.; Weinhardt, C. (2011). "Understanding auction fever: A framework for emotional bidding". Electronic Markets. 21 (3): 197–207. doi:10.1007/s12525-011-0068-9.

- ↑ Adam, M.T.P.; Krämer, J.; Müller, M. (2015). "Auction fever! How time pressure and social competition affect bidders arousal and bids in retail auctions". Journal of Retailing. 91 (3): 468–485. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2015.01.003.

- ↑ "Auction Jargon, Decoded: Basic Auction Terminology". Dakil.com. Dakil Auctioneers. February 28, 2014.

- 1 2 "Auction Jargon, Decoded: Basic Auction Terminology". February 28, 2014.

- ↑ Journal of Economic Literature Classification System, American Economic Association, retrieved 2008-06-25 (D: Microeconomics, D4: Market Structure and Pricing, D44: Auctions)

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Auctions. |

- Klemperer, P. 1999. Auction theory: A guide to the literature. Journal of Economic Surveys

- Krishna, Vijay (2002), Auction Theory, San Diego, USA: Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-426297-X

- Milgrom, Paul (2004), Putting Auction Theory to Work, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55184-6

- Shubik, Martin (March 2004), The Theory of Money and Financial Institutions: Volume 1, Cambridge , Mass., USA: MIT Press, pp. 213–219, ISBN 0-262-69311-9

- Weber, Robert J. (1997). "Making more from less: Strategic demand reduction in the FCC spectrum auctions". Journal of Economics & Management Strategy. 6 (3): 529–548. doi:10.1111/j.1430-9134.1997.00529.x.

- Vickrey, William S. (1961). "Counterspeculation, auctions, and competitive sealed tenders". Journal of Finance. 16 (1): 8–37. JSTOR 2977633. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1961.tb02789.x.

Further reading

- Klemperer, Paul (2004), Auctions: Theory and Practice, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-11925-2 Draft edition available online

- Smith, Charles W. (1990), Auctions: Social Construction of Value, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-07201-4