Cardiomyopathy

| Cardiomyopathy | |

|---|---|

| |

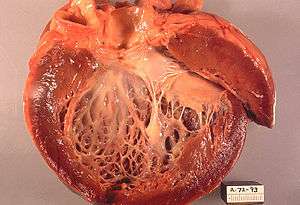

| Opened left ventricle showing thickening, dilatation, and subendocardial fibrosis noticeable as increased whiteness of the inside of the heart. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Symptoms | Shortness of breath, feeling tired, swelling of the legs[1] |

| Complications | Heart failure, irregular heart beat, sudden cardiac death[2][1] |

| Types | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, dilated cardiomyopathy, restrictive cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, broken heart syndrome[3] |

| Causes | Unknown, genetic, alcohol, heavy metals, amyloidosis, stress[4][3] |

| Treatment | Depends on type and symptoms[5] |

| Frequency | 2.5 million with myocarditis (2015)[6] |

| Deaths | 354,000 with myocarditis (2015)[7] |

Cardiomyopathy is a group of diseases that affect the heart muscle.[8] Early on there may be few or no symptoms. Some people may have shortness of breath, feel tired, or have swelling of the legs due to heart failure. An irregular heart beat may occur as well as fainting.[1] Those affected are at an increased risk of sudden cardiac death.[2]

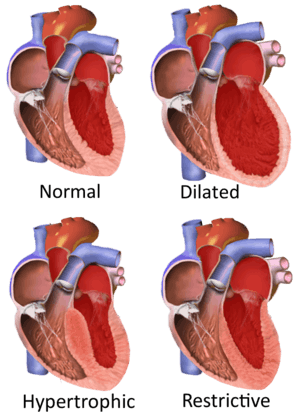

Types of cardiomyopathy include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, dilated cardiomyopathy, restrictive cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, and broken heart syndrome. In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy the heart muscle enlarges and thickens. In dilated cardiomyopathy the ventricles enlarge and weaken. In restrictive cardiomyopathy the ventricle stiffens.[3]

The cause is frequently unknown. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is often and dilated cardiomyopathy in a third of cases, is inherited from a person's parents. Dilated cardiomyopathy may also result from alcohol, heavy metals, coronary heart disease, cocaine use, and viral infections. Restrictive cardiomyopathy may be caused by amyloidosis, hemochromatosis, and some cancer treatments.[4] Broken heart syndrome is caused by extreme emotional or physical stress.[3]

Treatment depends on the type of cardiomyopathy and the degree of symptoms. Treatments may include lifestyle changes, medications, or surgery.[5] In 2015 cardiomyopathy and myocarditis affected 2.5 million people.[6] Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy affects about 1 in 500 people while dilated cardiomyopathy affects 1 in 2,500.[3][9] They resulted in 354,000 deaths up from 294,000 in 1990.[10][7] Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia is more common in young people.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of cardiomyopathies may include fatigue, swelling of the lower extremities and shortness of breath.[11]

Cause

Cardiomyopathies are either confined to the heart or are part of a generalized systemic disorder, both often leading to cardiovascular death or progressive heart failure-related disability. Other diseases that cause heart muscle dysfunction are excluded, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, or abnormalities of the heart valves.[12]

Earlier, simpler, categories such as intrinsic, (defined as weakness of the heart muscle without an identifiable external cause), and extrinsic, (where the primary pathology arose outside the myocardium itself), became more difficult to sustain. For example, as more external causes were recognized, the intrinsic category became smaller. Alcoholism, for example, has been identified as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy, as has drug toxicity, and certain infections (including Hepatitis C). On the other hand, molecular biology and genetics have given rise to the recognition of various genetic causes, increasing the intrinsic category. For example, mutations in the cardiac desmosomal genes as well as in the DES gene may cause arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC).[13][14]

At the same time, a more clinical categorization of cardiomyopathy as 'hypertrophied', 'dilated', or 'restrictive',[15] became difficult to maintain when it became apparent that some of the conditions could fulfill more than one of those three categories at any particular stage of their development. The current American Heart Association definition divides cardiomyopathies into primary, which affect the heart alone, and secondary, which are the result of illness affecting other parts of the body. These categories are further broken down into subgroups which incorporate new genetic and molecular biology knowledge.[16]

Types

Cardiomyopathies can be classified using different criteria:[17]

- Primary/intrinsic cardiomyopathies[18]

- Genetic

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)

- LV non-compaction

- Ion Channelopathies

- Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM)

- Acquired

- Genetic

- Secondary/extrinsic cardiomyopathies[18]

- Metabolic/storage

- Fabry's disease

- hemochromatosis

- Endomyocardial

- Endocrine

- Cardiofacial

- Neuromuscular

- Other

- Obesity-associated cardiomyopathy[19]

- Metabolic/storage

Mechanism

Symptoms may include shortness of breath after physical exertion, fatigue, and swelling of the feet, legs, or abdomen. Additionally, arrhythmias and chest pain may be present.[11]

The pathophysiology of cardiomyopathies is better understood at the cellular level with advances in molecular techniques. Mutant proteins can disturb cardiac function in the contractile apparatus (or mechanosensitive complexes). Cardiomyocyte alterations and their persistent responses at the cellular level cause changes that are correlated with sudden cardiac death and other cardiac problems.[20]

Diagnosis

Among the diagnostic procedures done to determine a cardiomyopathy are:[11]

- Physical exam

- Family history

- Blood test

- EKG

- Echocardiogram

- Stress test

- Genetic testing

Treatment

Treatment may include suggestion of lifestyle changes to better manage the condition. Treatment depends on the type of cardiomyopathy and condition of disease, but may include medication (conservative treatment) or iatrogenic/implanted pacemakers for slow heart rates, defibrillators for those prone to fatal heart rhythms, ventricular assist devices (VADs) for severe heart failure, or ablation for recurring dysrhythmias that cannot be eliminated by medication or mechanical cardioversion. The goal of treatment is often symptom relief, and some patients may eventually require a heart transplant.[11]

References

- 1 2 3 "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Cardiomyopathy?". NHLBI. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Who Is at Risk for Cardiomyopathy?". NHLBI. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Types of Cardiomyopathy". NHLBI. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- 1 2 "What Causes Cardiomyopathy?". NHLBI. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- 1 2 "How Is Cardiomyopathy Treated?". NHLBI. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- 1 2 GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.". Lancet (London, England). 388 (10053): 1545–1602. PMC 5055577

. PMID 27733282. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6.

. PMID 27733282. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. - 1 2 GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.". Lancet (London, England). 388 (10053): 1459–1544. PMC 5388903

. PMID 27733281. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1.

. PMID 27733281. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. - ↑ "What Is Sudden Cardiac Arrest?". NHLBI. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ Practical Cardiovascular Pathology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2010. p. 148. ISBN 9781605478418.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. PMC 4340604

. PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2.

. PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. - 1 2 3 4 "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Cardiomyopathy? - NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ Lakdawala, NK; Stevenson, LW; Loscalzo, J (2015). "Chapter 287". In Kasper, DL; Fauci, AS; Hauser, SL; Longo, DL; Jameson, JL; Loscalzo, J. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (19th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 1553. ISBN 978-0-07-180215-4.

- ↑ Klauke B, Kossmann S, Gaertner A, Brand K, Stork I, Brodehl A, Dieding M, Walhorn V, Anselmetti D, Gerdes D, Bohms B, Schulz U, Zu Knyphausen E, Vorgerd M, Gummert J, Milting H (2010). "De novo desmin-mutation N116S is associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy". Hum. Mol. Genet. 19 (23): 4595–607. PMID 20829228. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq387.

- ↑ Brodehl A, Hedde PN, Dieding M, Fatima A, Walhorn V, Gayda S, Šarić T, Klauke B, Gummert J, Anselmetti D, Heilemann M, Nienhaus GU, Milting H (2012). "Dual color photoactivation localization microscopy of cardiomyopathy-associated desmin mutants". J. Biol. Chem. 287 (19): 16047–57. PMC 3346104

. PMID 22403400. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.313841.

. PMID 22403400. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.313841. - ↑ Valentin Fuster; John Willis Hurst (2004). Hurst's the heart. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 1884–. ISBN 978-0-07-143225-2. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ↑ McCartan C, Maso R, Jayasinghe SR, Griffiths LR (2012). "Cardiomyopathy Classification: Ongoing Debate in the Genomics Era". Biochem Res Int. 2012: 796926. PMC 3423823

. PMID 22924131. doi:10.1155/2012/796926.

. PMID 22924131. doi:10.1155/2012/796926. - ↑ Vinay, Kumar (2013). Robbins Basic Pathology. Elsevier. p. 396. ISBN 978-1-4377-1781-5.

- 1 2 Maron, Barry J.; Towbin, Jeffrey A.; Thiene, Gaetano; Antzelevitch, Charles; Corrado, Domenico; Arnett, Donna; Moss, Arthur J.; Seidman, Christine E.; Young, James B. (11 April 2006). "Contemporary Definitions and Classification of the Cardiomyopathies". Circulation. 113 (14): 1807–1816. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 16567565. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174287. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ↑ Lipshultz, Steven E.; Messiah, Sarah E.; Miller, Tracie L. (2012-04-05). Pediatric Metabolic Syndrome: Comprehensive Clinical Review and Related Health Issues. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 200. ISBN 9781447123651.

- ↑ Harvey, Pamela A.; Leinwand, Leslie A. (2011-08-08). "Cellular mechanisms of cardiomyopathy". The Journal of Cell Biology. 194 (3): 355–365. ISSN 0021-9525. PMC 3153638

. PMID 21825071. doi:10.1083/jcb.201101100.

. PMID 21825071. doi:10.1083/jcb.201101100.

Further reading

- Boudina, Sihem; Abel, Evan Dale (1 March 2010). "Diabetic cardiomyopathy, causes and effects". Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders. 11 (1): 31–39. ISSN 1389-9155. PMC 2914514

. PMID 20180026. doi:10.1007/s11154-010-9131-7.

. PMID 20180026. doi:10.1007/s11154-010-9131-7. - Marian, A. J.; Roberts, Robert (1 April 2001). "The Molecular Genetic Basis for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy". Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 33 (4): 655–670. ISSN 0022-2828. PMC 2901497

. PMID 11273720. doi:10.1006/jmcc.2001.1340.

. PMID 11273720. doi:10.1006/jmcc.2001.1340. - Acton, Q. Ashton (2013). Advances in Heart Research and Application: 2013 Edition. Scholarly Editions. ISBN 978-1-481-68280-0.

External links

| Classification |

V · T · D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Look up cardiomyopathy in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |