Multicellular organism

| Multicellular organism Temporal range: Mesoproterozoic–present | |

|---|---|

| |

| In this image, a wild-type Caenorhabditis elegans is stained to highlight the nuclei of its cells. | |

| Scientific classification | |

Multicellular organisms are organisms that consist of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organisms.[1]

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni- and partially multicellular, like slime molds and social amoebae such as the genus Dictyostelium.

Multicellular organisms arise in various different ways, for example by cell division or by aggregation of many single cells.[2] Colonial organisms are the result of many identical individuals joining together to form a colony. However, it can often be hard to separate colonial protists from true multicellular organisms, because the two concepts are not distinct; colonial protists have been dubbed "pluricellular" rather than "multicellular".[3][4]

Evolutionary history

Orange labels: known ice ages.

Also see: Human timeline and Nature timeline

Occurrence

Multicellularity has evolved independently at least 46 times,[5][6] including in some prokaryotes, like cyanobacteria, myxobacteria, actinomycetes, Magnetoglobus multicellularis or Methanosarcina. However, complex multicellular organisms evolved only in six eukaryotic groups: animals, fungi, brown algae, red algae, green algae, and land plants.[7] It evolved repeatedly for Chloroplastida (green algae and land plants), once or twice for animals, once for brown algae, three times in the fungi (chytrids, ascomycetes and basidiomycetes)[8] and perhaps several times for slime molds and red algae.[9] The first evidence of multicellularity is from cyanobacteria-like organisms that lived 3–3.5 billion years ago.[5] To reproduce, true multicellular organisms must solve the problem of regenerating a whole organism from germ cells (i.e. sperm and egg cells), an issue that is studied in evolutionary developmental biology. Animals have evolved a considerable diversity of cell types in a multicellular body (100–150 different cell types), compared with 10–20 in plants and fungi.[10]

Loss of multicellularity

Loss of multicellularity occurred in some groups.[11] Fungi are predominantly multicellular, though early diverging lineages are largely unicellular (e.g. Microsporidia) and there have been numerous reversions to unicellularity across fungi (e.g. Saccharomycotina, Cryptococcus, and other yeasts).[12][13] It may also have occurred in some red algae (e.g. Porphyridium), but it is possible that they are primitively unicellular.[14] Loss of multicellularity is also considered probable in some green algae (e.g. Chlorella vulgaris and some Ulvophyceae).[15][16] In other groups, generally parasites, a reduction of multicellularity occurred, in number or types of cells (e.g. the myxozoans, multicellular organisms, earlier thought to be unicellular, are probably extremely reduced cnidarians).[17]

Cancer

Multicellular organisms, especially long-living animals, face the challenge of cancer, which occurs when cells fail to regulate their growth within the normal program of development. Changes in tissue morphology can be observed during this process. Cancer in animals (metazoans) has often been described as a loss of multicellularity.[18] There is a discussion about the possibility of existence of cancer in other multicellular organisms[19][20] or even in protozoa.[21] For example, plant galls have been characterized as tumors[22] but some authors argue that plants do not develop cancer.[23]

Separation of somatic and germ cells

In some multicellular groups, which are called Weismannists, a separation between a sterile somatic cell line and a germ cell line evolved. However, Weismannist development is relatively rare (e.g. vertebrates, arthropods, Volvox), as great part of species have the capacity for somatic embryogenesis (e.g. land plants, most algae, many invertebrates).[24][25]

Hypotheses for origin

One hypothesis for the origin of multicellularity is that a group of function-specific cells aggregated into a slug-like mass called a grex, which moved as a multicellular unit. This is essentially what slime molds do. Another hypothesis is that a primitive cell underwent nucleus division, thereby becoming a coenocyte. A membrane would then form around each nucleus (and the cellular space and organelles occupied in the space), thereby resulting in a group of connected cells in one organism (this mechanism is observable in Drosophila). A third hypothesis is that as a unicellular organism divided, the daughter cells failed to separate, resulting in a conglomeration of identical cells in one organism, which could later develop specialized tissues. This is what plant and animal embryos do as well as colonial choanoflagellates.[26][27]

Because the first multicellular organisms were simple, soft organisms lacking bone, shell or other hard body parts, they are not well preserved in the fossil record.[28] One exception may be the demosponge, which may have left a chemical signature in ancient rocks. The earliest fossils of multicellular organisms include the contested Grypania spiralis and the fossils of the black shales of the Palaeoproterozoic Francevillian Group Fossil B Formation in Gabon (Gabonionta).[29] The Doushantuo Formation has yielded 600 million year old microfossils with evidence of multicellular traits.[30]

Until recently, phylogenetic reconstruction has been through anatomical (particularly embryological) similarities. This is inexact, as living multicellular organisms such as animals and plants are more than 500 million years removed from their single-cell ancestors. Such a passage of time allows both divergent and convergent evolution time to mimic similarities and accumulate differences between groups of modern and extinct ancestral species. Modern phylogenetics uses sophisticated techniques such as alloenzymes, satellite DNA and other molecular markers to describe traits that are shared between distantly related lineages.

The evolution of multicellularity could have occurred in a number of different ways, some of which are described below:

The symbiotic theory

This theory suggests that the first multicellular organisms occurred from symbiosis (cooperation) of different species of single-cell organisms, each with different roles. Over time these organisms would become so dependent on each other they would not be able to survive independently, eventually leading to the incorporation of their genomes into one multicellular organism.[31] Each respective organism would become a separate lineage of differentiated cells within the newly created species.

This kind of severely co-dependent symbiosis can be seen frequently, such as in the relationship between clown fish and Riterri sea anemones. In these cases, it is extremely doubtful whether either species would survive very long if the other became extinct. However, the problem with this theory is that it is still not known how each organism's DNA could be incorporated into one single genome to constitute them as a single species. Although such symbiosis is theorized to have occurred (e.g. mitochondria and chloroplasts in animal and plant cells—endosymbiosis), it has happened only extremely rarely and, even then, the genomes of the endosymbionts have retained an element of distinction, separately replicating their DNA during mitosis of the host species. For instance, the two or three symbiotic organisms forming the composite lichen, although dependent on each other for survival, have to separately reproduce and then re-form to create one individual organism once more.

The cellularization (syncytial) theory

This theory states that a single unicellular organism, with multiple nuclei, could have developed internal membrane partitions around each of its nuclei.[32] Many protists such as the ciliates or slime molds can have several nuclei, lending support to this hypothesis. However, the simple presence of multiple nuclei is not enough to support the theory. Multiple nuclei of ciliates are dissimilar and have clear differentiated functions. The macronucleus serves the organism's needs, whereas the micronucleus is used for sexual reproduction with exchange of genetic material. Slime molds syncitia form from individual amoeboid cells, like syncitial tissues of some multicellular organisms, not the other way round. To be deemed valid, this theory needs a demonstrable example and mechanism of generation of a multicellular organism from a pre-existing syncytium.

The colonial theory

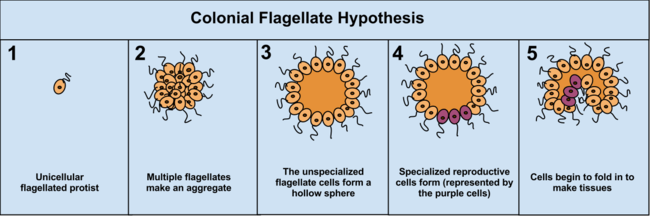

The Colonial Theory of Haeckel, 1874, proposes that the symbiosis of many organisms of the same species (unlike the symbiotic theory, which suggests the symbiosis of different species) led to a multicellular organism. At least some, it is presumed land-evolved, multicellularity occurs by cells separating and then rejoining (e.g. cellular slime molds) whereas for the majority of multicellular types (those that evolved within aquatic environments), multicellularity occurs as a consequence of cells failing to separate following division.[33] The mechanism of this latter colony formation can be as simple as incomplete cytokinesis, though multicellularity is also typically considered to involve cellular differentiation.[34]

The advantage of the Colonial Theory hypothesis is that it has been seen to occur independently in 16 different protoctistan phyla. For instance, during food shortages the amoeba Dictyostelium groups together in a colony that moves as one to a new location. Some of these amoeba then slightly differentiate from each other. Other examples of colonial organisation in protista are Volvocaceae, such as Eudorina and Volvox, the latter of which consists of up to 500–50,000 cells (depending on the species), only a fraction of which reproduce.[35] For example, in one species 25–35 cells reproduce, 8 asexually and around 15–25 sexually. However, it can often be hard to separate colonial protists from true multicellular organisms, as the two concepts are not distinct; colonial protists have been dubbed "pluricellular" rather than "multicellular".[3]

The Synzoospore theory

Some authors suggest that the origin of multicellularity, at least in Metazoa, occurred due to a transition from temporal to spatial cell differentiation, rather than through a gradual evolution of cell differentiation, as affirmed in Haeckel’s Gastraea theory.[36]

GK-PID

About 800 million years ago,[37] a minor genetic change in a single molecule called guanylate kinase protein-interaction domain (GK-PID) may have allowed organisms to go from a single cell organism to one of many cells.[38]

The role of viruses

Genes borrowed from viruses have recently been identified as playing a crucial role in the differentiation of multicellular tissues and organs and even in sexual reproduction, in the fusion of egg cell and sperm. Such fused cells are also involved in metazoan membranes such as those that prevent chemicals crossing the placenta and the brain body separation. Two viral components have been identified. The first is syncytin, which came from a virus. The second identified in 2007 is called EFF1, which helps form the skin of Caenorhabditis elegans, part of a whole family of FF proteins. Felix Rey, of the Pasteur Institute in Paris has constructed the 3D structure of the EFF1 protein[39] and shown it does the work of linking one cell to another, in viral infections. The fact that all known cell fusion molecules are viral in origin suggests that they have been vitally important to the inter-cellular communication systems that enabled multicellularity. Without the ability of cellular fusion, colonies could have formed, but anything even as complex as a sponge would not have been possible.[40]

Advantages

Multicellularity allows an organism to exceed the size limits normally imposed by diffusion: single cells with increased size have a decreased surface-to-volume ratio and have difficulty absorbing sufficient nutrients and transporting them throughout the cell. Multicellular organisms thus have the competitive advantages of an increase in size without its limitations. They can have longer lifespans as they can continue living when individual cells die. Multicellularity also permits increasing complexity by allowing differentiation of cell types within one organism.

See also

References

- ↑ Becker, Wayne M.; et al. (2008). The world of the cell. Pearson Benjamin Cummings. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-321-55418-5.

- ↑ S. M. Miller (2010). "Volvox, Chlamydomonas, and the evolution of multicellularity". Nature Education. 3 (9): 65.

- 1 2 Brian Keith Hall; Benedikt Hallgrímsson; Monroe W. Strickberger (2008). Strickberger's evolution: the integration of genes, organisms and populations (4th ed.). Hall/Hallgrímsson. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-7637-0066-9.

- ↑ Adl, Sina; et al. (October 2005). "The New Higher Level Classification of Eukaryotes with Emphasis on the Taxonomy of Protists". J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 52: 399–451. PMID 16248873. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- 1 2 Grosberg, RK; Strathmann, RR (2007). "The evolution of multicellularity: A minor major transition?" (PDF). Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 38: 621–654. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102403.114735.

- ↑ Parfrey, L.W.; Lahr, D.J.G. (2013). "Multicellularity arose several times in the evolution of eukaryotes" (PDF). BioEssays. 35 (4): 339–347. doi:10.1002/bies.201200143.

- ↑ http://public.wsu.edu/~lange-m/Documnets/Teaching2011/Popper2011.pdf

- ↑ Niklas, KJ (2014). "The evolutionary-developmental origins of multicellularity". Am. J. Bot. 101: 6–25. PMID 24363320. doi:10.3732/ajb.1300314.

- ↑ Bonner, John Tyler (1998). "The Origins of Multicellularity" (PDF). Integrative Biology. 1 (1): 27–36. ISSN 1093-4391. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6602(1998)1:1<27::AID-INBI4>3.0.CO;2-6. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012.

- ↑ Margulis, L. & Chapman, M.J. (2009). Kingdoms and Domains: An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on Earth ([4th ed.]. ed.). Amsterdam: Academic Press/Elsevier. p. 116.

- ↑ Seravin L. N. (2001) The principle of counter-directional morphological evolution and its significance for constructing the megasystem of protists and other eukaryotes. Protistology 2: 6–14, .

- ↑ Parfrey, L.W. & Lahr, D.J.G. (2013), p. 344.

- ↑ Medina, M.; Collins, A. G.; Taylor, J. W.; Valentine, J. W.; Lipps, J. H.; Zettler, L. A. Amaral; Sogin, M. L. (2003). "Phylogeny of Opisthokonta and the evolution of multicellularity and complexity in Fungi and Metazoa". International Journal of Astrobiology. 2 (3): 203–211. doi:10.1017/s1473550403001551.

- ↑ Seckbach, Joseph, Chapman, David J. [eds.]. (2010). Red algae in the genomic age. New York, NY, U.S.A.: Springer, p. 252, .

- ↑ Cocquyt, E.; Verbruggen, H.; Leliaert, F.; De Clerck, O. (2010). "Evolution and Cytological Diversification of the Green Seaweeds (Ulvophyceae)". Mol. Biol. Evol. 27 (9): 2052–2061. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 20368268. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq091.

- ↑ Richter, Daniel Joseph: The gene content of diverse choanoflagellates illuminates animal origins, 2013.

- ↑ http://tolweb.org/Myxozoa/2460

- ↑ Davies, P. C. W.; Lineweaver, C. H. (2011). "Cancer tumors as Metazoa 1.0: tapping genes of ancient ancestors". Physical Biology. 8 (1): 015001. PMC 3148211

. PMID 21301065. doi:10.1088/1478-3975/8/1/015001.

. PMID 21301065. doi:10.1088/1478-3975/8/1/015001. - ↑ Richter, D. J. (2013), p. 11.

- ↑ Gaspar, T.; Hagege, D.; Kevers, C.; Penel, C.; Crèvecoeur, M.; Engelmann, I.; Greppin, H.; Foidart, J. M. (1991). "When plant teratomas turn into cancers in the absence of pathogens". Physiologia Plantarum. 83 (4): 696–701. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1991.tb02489.x.

- ↑ Lauckner, G. (1980). Diseases of protozoa. In: Diseases of Marine Animals. Kinne, O. (ed.). Vol. 1, p. 84, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK.

- ↑ Riker, A. J. (1958). "Plant tumors: Introduction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 44: 338–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.44.4.338.

- ↑ Doonan, J.; Hunt, T. (1996). "Cell cycle. Why don't plants get cancer?". Nature. 380: 481–2. PMID 8606760. doi:10.1038/380481a0.

- ↑ Ridley M (2004) Evolution, 3rd edition. Blackwell Publishing, p. 295-297.

- ↑ Niklas, K. J. (2014) The evolutionary-developmental origins of multicellularity.

- ↑ Multicellular development in a choanoflagellate; Stephen R. Fairclough, Mark J. Dayel and Nicole King

- ↑ In a Single-Cell Predator, Clues to the Animal Kingdom’s Birth

- ↑ A H Knoll, 2003. Life on a Young Planet. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00978-3 (hardcover), ISBN 0-691-12029-3 (paperback). An excellent book on the early history of life, very accessible to the non-specialist; includes extensive discussions of early signatures, fossilization, and organization of life.

- ↑ El Albani, Abderrazak; et al. (1 July 2010). "Large colonial organisms with coordinated growth in oxygenated environments 2.1 Gyr ago". Nature. 466 (7302): 100–104. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20596019. doi:10.1038/nature09166.

- ↑ Chen, L.; Xiao, S.; Pang, K.; Zhou, C.; Yuan, X. (2014). "Cell differentiation and germ–soma separation in Ediacaran animal embryo-like fossils". Nature. 516: 238–241. doi:10.1038/nature13766.

- ↑ Margulis, Lynn (1998). Symbiotic Planet: A New Look at Evolution. New York: Basic Books. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-465-07272-9.

- ↑ Hickman CP, Hickman FM (8 July 1974). Integrated Principles of Zoology (5th ed.). Mosby. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-8016-2184-0.

- ↑ Wolpert, L.; Szathmáry, E. (2002). "Multicellularity: Evolution and the egg". Nature. 420 (6917): 745. PMID 12490925. doi:10.1038/420745a.

- ↑ Kirk, D. L. (2005). "A twelve-step program for evolving multicellularity and a division of labor". BioEssays. 27 (3): 299–310. PMID 15714559. doi:10.1002/bies.20197.

- ↑ AlgaeBase. Volvox Linnaeus, 1758: 820.

- ↑ Mikhailov K. V., Konstantinova A. V., Nikitin M. A., Troshin P. V., Rusin L., Lyubetsky V., Panchin Y., Mylnikov A. P., Moroz L. L., Kumar S. & Aleoshin V. V. (2009). The origin of Metazoa: a transition from temporal to spatial cell differentiation. Bioessays, 31(7), 758–768, .

- ↑ Erwin, Douglas H. (9 November 2015). "Early metazoan life: divergence, environment and ecology". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 370 (20150036). doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0036. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (7 January 2016). "Genetic Flip Helped Organisms Go From One Cell to Many". New York Times. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ↑ Jamin, M, H Raveh-Barak, B Podbilewicz, FA Rey (2014) "Structural basis of eukaryotic cell-cell fusion" (Cell, Volume 157, Issue 2, 10 April 2014), Pages 407–419

- ↑ Slezak, Michael (2016), "No Viruses? No skin or bones either" (New Scientist, No. 2958, 1 March 2014) p.16