Muisca numerals

|

| Muisca |

|---|

| Topics |

| Geography |

| The Salt People |

| Main neighbours |

| History & timeline |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

|

| Hindu–Arabic numeral system |

| East Asian |

| Alphabetic |

| Former |

| Positional systems by base |

| Non-standard positional numeral systems |

| List of numeral systems |

Muisca numerals were the numeric notation system used by the Muisca, one of the four advanced civilizations of the Americas before the Spanish conquest of the Muisca. Just like the Mayas, the Muisca had a vigesimal numerical system, based on multiples of twenty (Chibcha: gueta). The Muisca numerals were based on counting with fingers and toes. They had specific numbers from one to ten, yet for the numbers between eleven and nineteen they used "foot one" (11) to "foot nine" (19). The number 20 was the 'perfect' number for the Muisca which is visible in their calendar. To calculate higher numbers than 20 they used multiples of their 'perfect' number; gue-muyhica would be "20 times 4", so 80. To describe "50" they used "20 times 2 plus 10"; gue-bosa asaqui ubchihica, transcripted from guêboʒhas aſaqɣ hubchìhicâ.[1] In their calendar, which was lunisolar, they only counted from one to ten and twenty. Each number had a special meaning, related to their deities and certain animals, especially the abundant toads.[2]

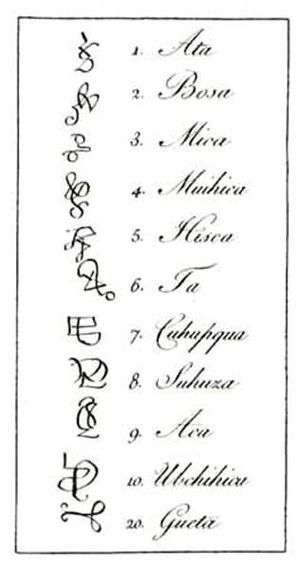

For the representation of their numbers they used hieroglyphs drawn inspired by their natural surroundings, especially toads; ata ("one") and aca ("nine") were both derived from the animals so abundant on the Bogotá savanna and other parts of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense where the Muisca lived in their confederation.

Most important scholars who provided knowledge about the Muisca numerals were Bernardo de Lugo (1619),[1] Pedro Simón (17th century), Alexander von Humboldt and José Domingo Duquesne (late 18th and early 19th century) and Liborio Zerda.[3][4][5][6][7]

Numerals

The Muisca used a vigesimal counting system and counted primarily with their fingers and secondarily with their toes. Their system went from 1 to 10 and for higher numerations they used the prefix quihicha or qhicha, which means "foot" in their Chibcha language Muysccubun. Eleven became thus "foot one", twelve: "foot two", etc. As in the other pre-Columbian civilizations, the number 20 was special. It was the total number of all body extremities; fingers and toes. The Muisca used two forms to express twenty: "foot ten"; quihícha ubchihica or their exclusive word gueta, derived from gue, which means "house". Numbers between 20 and 30 were counted gueta asaqui ata ("twenty plus one"; 21), gueta asaqui ubchihica ("twenty plus ten"; 30). Larger numbers were counted as multiples of twenty; gue-bosa ("20 times 2"; 40), gue-hisca ("20 times 5"; 100).[3]

Numbers 1 to 10 and 20

| Number | Humboldt, 1807[3] | De Lugo, 1619[1] | Muisca hieroglyphs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ata |  | |

| 2 | bozha / bosa | boʒha | |

| 3 | mica | ||

| 4 | mhuyca / muyhica | mhuɣcâ | |

| 5 | hicsca / hisca | hɣcſcâ | |

| 6 | taa[8] | ||

| 7 | qhupqa / cuhupqua | qhûpqâ | |

| 8 | shuzha / suhuza | shûʒhâ | |

| 9 | aca | ||

| 10 | hubchibica / ubchihica | hubchìhicâ | |

| 20 | quihicha ubchihica gueta |

qhicħâ hubchìhicâ guêata | |

Higher numbers

| Number | Humboldt, 1807[3] | De Lugo, 1619[1] |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | quihicha ata | qhicħâ ata |

| 12 | quihicha bosa | qhicħâ boʒha |

| 13 | quihicha mica | qhicħâ mica |

| 14 | quihicha mhuyca | qhicħâ mhuɣcâ |

| 15 | quihicha hisca | qhicħâ hɣcſcâ |

| 16 | quihicha ta | qhicħâ ta |

| 17 | quihicha cuhupqua | qhicħâ qhûpqâ |

| 18 | quihicha suhuza | qhicħâ shûʒhâ |

| 19 | quihicha aca | qhicħâ aca |

| 20 | gueta | guêata |

| 21 | guetas asaqui ata | guêatas aſaqɣ ata |

| 30 | guetas asaqui ubchihica | guêatas aſaqɣ hubchìhicâ |

| 40 | gue-bosa | guêboʒha |

| 50 | gue-bosa asaqui ubchihica | guêboʒhas aſaqɣ hubchìhicâ |

| 60 | gue-mica | guêmica |

| 70 | gue-mica asaqui ubchihica | guêmicas aſaqɣ hubchìhicâ |

| 80 | gue-muyhica | guêmhuɣcâ |

| 90 | gue-muyhica asaqui ubchihica | guêmhuɣcâs aſaqɣ hubchìhicâ |

| 99 | gue-muyhica asaqui quihicha aca | guêmhuɣcâs aſaqɣ qhicħâ aca |

| 100 | gue-hisca | guêhɣcſcâ |

| 101 | gue-hisca asaqui ata | guêhɣcſcâs aſaqɣ ata |

| 110 | gue-hisca asaqui hubchihica | guêhɣcſcâs aſaqɣ hubchìhicâ |

| 120 | gue-ta | guêta |

| 150 | gue-muyhica asaqui hubchihica | guêqhûpqâs aſaqɣ hubchìhicâ |

| 199 | gue-aca asaqui quihicha aca | guêacas aſaqɣ qhicħâ aca |

| 200 | gue-ubchihica | guêhubchìhicâ |

| 250 | gue-quihicha bozha asaqui hubchihica | guêqhicħâ boʒhas aſaqɣ hubchìhicâ |

| 300 | gue-chihica hisca | guêqhicħâ hɣcſcâ |

| 365 | gue-chihica suhuza asaqui hisca | guêqhicħâ shûʒhâs aſaqɣ hɣcſcâ |

| 399 | gue-chihica aca asaqui quihicha aca | guêqhicħâ acas aſaqɣ qhicħâ aca |

See also

- Muisca art

- Muysccubun

- Quipu - Inca numerals

- Muisca calendar

- Maya numerals

References

Bibliography

- Duquesne, José Domingo. 1795. Disertación sobre el calendario de los muyscas, indios naturales de este Nuevo Reino de Granada - Dissertation about the Muisca calendar, indigenous people of this New Kingdom of Granada, 1–17. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Humboldt, Alexander von. 1807. VI.Sitios de las Cordilleras y monumentos de los pueblos indígenas de América - Calendario de los indios muiscas - Parte 1 - Views of the Cordilleras and Monuments of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas - Muisca calendar - Part 1. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Humboldt, Alexander von. 1807. VI.Sitios de las Cordilleras y monumentos de los pueblos indígenas de América - Calendario de los indios muiscas - Parte 2. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Humboldt, Alexander von. 1807. VI.Sitios de las Cordilleras y monumentos de los pueblos indígenas de América - Calendario de los indios muiscas - Parte 3. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Izquierdo Peña, Manuel Arturo. 2009. The Muisca Calendar: An approximation to the timekeeping system of the ancient native people of the northeastern Andes of Colombia, 1–170. Université de Montréal. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Zerda, Liborio. 1947 (1883). El Dorado. Accessed 2016-07-08.