Muhammad III, Sultan of Granada

| Muhammad III | |

|---|---|

| Sultan of Granada | |

| Reign | April 1302 – 14 March 1309 |

| Predecessor | Muhammed II al-Faqih |

| Successor | Nasr, Sultan of Granada |

| House | Nasrid dynasty |

| Father | Muhammed II al-Faqih |

| Religion | Islam |

Muhammed III (1257- after 1309) was a son of Muhammed II al-Faqih and the third Nasrid ruler of the Emirate of Granada in Al-Andalus on the Iberian Peninsula. On April 8, 1302 he ascended the Granadan Sultan's throne after the death of his father Muhammed II al-Faqih. During the first few weeks of his reign, Muhammed III negotiated peace treaties with the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon.

Background

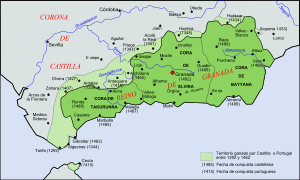

In the 1230s, Muhammad III's grandfather, Muhammad I, set up the Emirate of Granada, which eventually became the last independent Muslim state in the Iberian peninsula. Through a combination of diplomatic and military maneuvers, the kingdom succeeded in maintaining its independence, despite being surrounded by larger neighbors, Castile and the Marinid state (based in Morocco). Under the reigns of Muhammad I and his successor Muhammad II, Granada intermittently entered into alliance or went to war with either of these powers, or encouraged them to fight one another, in order to avoid being dominated by either.[1]

Rule

Accession

Just before his death, Muhammad II—Muhammad III's father—oversaw a successful campaign against Castile, taking advantage of Castile's concurrent war against Aragon as well as the minority of the Castilian king Ferdinand IV. In September 1301 Muhammad secured a peace agreement in which, among others, Castile agreed to return Tarifa—an important port on the Straits of Gibraltar[2]—to Granada. This agreement was ratified in January 1302, but was never put into effect due to Muhammad II's death shortly after.[3]

Muhammad II died in April 1302 after 29 years of rule. There were allegations, cited by Ibn al-Khatib, that Muhammad III, perhaps impatient to assume power, killed his father by poison, although this rumor was never confirmed.[4][5][lower-alpha 1] An anecdote says that during his accession, when a poet recited: For whom are the banners today unfurled? For whom do the troops' neath their standards march, he responded: "For this fool you can see before you all".[6]

Peace with Castile and Aragon

As Muhammad II's agreement with Castile had been aborted, the war continued. Two weeks into Muhammad III's rule, Granadan troops took Bedmar, near Jaén. Muhammad III then started negotiations. In 1303, Castile sent a delegation led by the royal chancellor Fernando Gómez de Toledo to Granada. Castile offered to meet nearly all of Granada's demands, including Bedmar, Alcaudete, Quesada. Tarifa—which had been offered to Muhammad II before his death—was to be kept by Castile. In exchange, Muhammad would agree to become Ferdinand's vassal and pay the parias (tribute), a typical peace arrangement between the two kingdoms. The treaty would last three years. In 1304, Aragon also concluded its war with Castile (the Treaty of Torrellas), and assented to the Granada–Castile treaty, therefore creating peace between the three kingdoms, and leaving the Marinids isolated.[7]

The agreement, and the resulting alliance with Castile and Aragon, gave Granada peace as well as a dominant position in the Straits of Gibraltar. However it created its own problems. Domestically, many were not happy with the alliance with the Christians, especially the Volunteers of the Faith, a military group who came to Granada to fight a holy war. The Marinid state was offended by the tripartite alliance[8] against it. Aragon, while part of the alliance, were worried that a strong Castile-Granada relation would mean that the bloc could establish a choke-hold on the Strait and therefore devastate Aragonese trade. James II of Aragon sent an envoy, Bernat de Sarrià to the Marinid Sultan Abu Yaqub Yusuf, for negotiations—although ultimately these were unsuccessful.[9]

Decline

Despite efforts to allay its fear by the Granadan vizier al-Dani's, Aragon continued diplomatic efforts against Granada. These culminated in 1308, when Aragon and Castile concluded the Treaty of Alcalá de Henares. The Christian kingdoms agreed to attack Granada, not sign separate peace, and then divide its territories between them. Aragon would gain one sixth of the kingdom and Castile would gain the rest.[10]

In the meantime, Granada also moved against the Marinids, trying to take over Ceuta across the Straits. In 1304, the inhabitants of Ceuta declared independence from the Marinids. Granadan agents such as Abu Said Faraj, the governor of Malaga, took part in encouraging the rebellion. Later, Granadan forces fought with the rebels and 1307 Muhammad III declared himself overlord of Ceuta. Prior to 1307, the Marinids were in a war with the Kingdom of Tlemcen and thus were not able to take strong action in Ceuta. However in 1307, Abu Yaqub Yusuf was assassinated and then succeeded by Abu Thabit Amir. Abu Thabit ended the war against Tlemcen, and brought the Marinids into alliance with Castile and Aragon against Granada.[11]

Ousting

With Granada's three neighbors arrayed against it, Muhammad III became highly unpopular at home. In March 14, 1309 a palace coup deposed Muhammad and executed his vizier, Ibn al-Hakim al-Rundi. Ibn al-Hakim, who since 1303 was titled dhu al-wizaratayn ("the holder of two vizierate") was seen as the real power in the state and was the main target of the popular anger. He had been known for his wealth and extravagant lifestyle. The people of Granada sacked his palace, and his political rival Atiq ibn al-Mawl personally killed him. As for Muhammad III, he was forced to abdicate, but was allowed to live in Almuñécar, largely unmolested until his death. He was replaced by his brother Nasr.[12]

Personality

Muhammad III had a reputation of cruelty and brutality. Historian Ibn al-Khatib, active in mid-fourteenth century Granada, wrote that at the start of his reign he imprisoned his father's household troops and then refused to feed them. This remained for days until some of the prisoners had to eat their dead colleagues due to sheer hunger. When a guard gave them leftover food out of compassion, Muhammad had him executed in such a way that the blood flowed into the cell where the prisoners were held. An unconfirmed allegation mentioned by ibn al-Khatib said that he murdered his father. In addition to the cruelty, he was known to like reading well into the night, and his poor eyesight was perhaps due to this.[5][13]

Legacy

In contrast to Muhammad I and II who enjoyed long and stable reigns, Muhammad III was deposed after seven years of rule. Historians gave him the epithet al-makhlu' ("the deposed"), which was exclusively identified with him even though many of his successors were also deposed.[14]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 163, citing Ibn al-Khatib: "A story was put about that [Muhammad II] had been poisoned by a sweetmeat administered by his heir." Kennedy 2014, p. 285: "It was alleged that [Muhammad III] had in fact poisoned his father."

References

Citation

- ↑ Harvey 1992, pp. 160, 165.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 151.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 163.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, pp. 163, 166.

- 1 2 Kennedy 2014, p. 285.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 167.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 170.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, pp. 167–168.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 168.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 169.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, pp. 169–170,189.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 166.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 165.

Bibliography

- The Alhambra From the Ninth Century to Yusuf I (1354). vol. 1. Saqi Books, 1997.

- Harvey, L. P. (1992). Islamic Spain, 1250 to 1500. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31962-9.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2014-06-11). Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of Al-Andalus. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87041-8.

| Muhammad III, Sultan of Granada Cadet branch of the Banu Khazraj Born: 1257 Died: 1314 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Muhammed II al-Faqih |

Sultan of Granada 1302–1309 |

Succeeded by Nasr |