FRELIMO

Mozambique Liberation Front Frente de Libertação de Moçambique | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | FRELIMO |

| Leader | Filipe Nyusi |

| Secretary-General | Eliseu Machava |

| Founder |

Eduardo Mondlane Samora Machel |

| Founded | 25 June 1962 |

| Merger of | MANU, UDENAMO and UNAMI |

| Headquarters |

Dar es Salaam (1962–75)[1] Maputo (1975–present) |

| Youth wing | Mozambican Youth Organisation |

| Women's wing | Mozambican Women Organisation |

| Veteran's League | Association of Combatants of the National Liberation Struggle |

| Ideology |

Democratic socialism Marxism–Leninism (1977–89)[2] |

| Political position | Centre-left to Left-wing |

| International affiliation | Socialist International |

| African affiliation | Former Liberation Movements of Southern Africa |

| Colours | Red |

| Slogan | Unity, Criticism, Unity[3] |

| Assembly of the Republic |

144 / 250 |

| SADC PF |

0 / 5 |

| Pan-African Parliament |

0 / 5 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

|

www | |

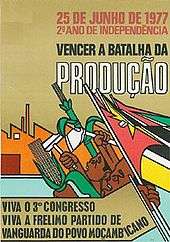

The Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) (Portuguese pronunciation: [fɾeˈlimu]), from the Portuguese Frente de Libertação de Moçambique is the dominant political party in Mozambique. Founded in 1962, FRELIMO began as a nationalist movement fighting for the independence of the Portuguese Overseas Province of Mozambique. Independence was achieved in June 1975 after the Carnation Revolution in Lisbon the previous year. At the party's 3rd Congress in February 1977, it became an officially Marxist–Leninist political party. It identified as the Frelimo Party (Partido Frelimo).[4]

The Frelimo Party has ruled Mozambique since then, first as a one-party state. It struggled through a long civil war (1976-1992) against an anti-Communist faction known as Mozambican National Resistance or RENAMO. The insurgents from RENAMO received support from the then white-minority governments of Rhodesia and South Africa. The Frelimo Party approved a new constitution in 1990, which established a multi-party system. Since democratic elections in 1994 and subsequent cycles, Frelimo has been elected as the majority party in the parliament of Mozambique.

Independence war (1962-1975)

After World War II, while many European nations were granting independence to their colonies, Portugal, under the Estado Novo regime, maintained that Mozambique and other Portuguese possessions were overseas territories of the metropole (mother country). Emigration to the colonies soared. Calls for Mozambican independence developed rapidly, and in 1962 several anti-colonial political groups formed FRELIMO. In September 1964, it initiated an armed campaign against Portuguese colonial rule. Portugal had ruled Mozambique for more than four hundred years; not all Mozambicans desired independence, and fewer still sought change through armed revolution.

FRELIMO was founded in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania on 25 June 1962, when three regionally based nationalist organizations: the Mozambican African National Union (MANU), National Democratic Union of Mozambique (UDENAMO), and the National African Union of Independent Mozambique (UNAMI,) merged into one broad-based guerrilla movement. Under the leadership of Eduardo Mondlane, elected president of the newly formed Mozambican Liberation Front, FRELIMO settled its headquarters in 1963 in Dar es Salaam. The Rev. Uria Simango was its first vice-president.

The movement could not then be based in Mozambique as the Portuguese opposed nationalist movements and the colony was controlled by the police. (The three founding groups had also operated as exiles.) Tanzania and its president, Julius Nyerere, were sympathetic to the Mozambican nationalist groups. Convinced by recent events, such as the Mueda massacre, that peaceful agitation would not bring about independence, FRELIMO contemplated the possibility of armed struggle from the outset. It launched its first offensive in September 1964.

During the ensuing war of independence, FRELIMO received support from China, the Soviet Union, the Scandinavian countries, and some non-governmental organisations in the West. Its initial military operations were in the North of the country; by the late 1960s it had established "liberated zones" in Northern Mozambique in which it, rather than the Portuguese, constituted the civil authority. In administering these zones, FRELIMO worked to improve the lot of the peasantry in order to receive their support. It freed them from subjugation to landlords and Portuguese-appointed "chiefs", and established cooperative forms of agriculture. It also greatly increased peasant access to education and health care. Often FRELIMO soldiers were assigned to medical assistance projects.

Its members' practical experiences in the liberated zones resulted in the FRELIMO leadership increasingly moving toward a Marxist policy. FRELIMO came to regard economic exploitation by Western capital as the principal enemy of the common Mozambican people, not the Portuguese as such, and not Europeans in general. Although it was an African nationalist party, it adopted a non-racial stance. Numerous whites and mulattoes were members.

.jpg)

The early years of the party, during which its Marxist direction evolved, were times of internal turmoil. Mondlane, along with Marcelino dos Santos, Samora Machel, Joaquim Chissano and a majority of the Party's Central Committee promoted the struggle not just for independence but to create a socialist society. The Second Party Congress, held in July 1968, approved the socialist goals. Mondlane was reelected party President and Uria Simango was re-elected vice-president.

After Mondlane's assassination in February 1969, Uria Simango took over the leadership, but his presidency was disputed. In April 1969, leadership was assumed by a triumvirate, with Machel and dos Santos supplementing Simango. After several months, in November 1969, Machel and dos Santos ousted Simango. He left FRELIMO and joined the small Revolutionary Committee of Mozambique (COREMO) liberation movement.

FRELIMO established some "liberated" zones (countryside zones with native rural populations controlled by FRELIMO guerrillas) in Northern Mozambique. The movement grew in strength during the ensuing decade. As FRELIMO's political campaign gained coherence, its forces advanced militarily, controlling one-third of the area of Mozambique by 1969, mostly in the northern and central provinces. It was not able to gain control of any urban centre, including none of the small cities and towns located inside the "liberated" zones.

In 1970 the guerrilla movement suffered heavy damage due to Portugal's Gordian Knot Operation (Operação Nó Górdio), which was masterminded by Kaúlza de Arriaga. By the early 1970s, FRELIMO's 7,000-strong guerrilla force had taken control of some parts of central and northern Mozambique. It was engaging a Portuguese force of approximately 60,000 soldiers.

The April 1974 "Carnation Revolution" in Portugal overthrew the Portuguese Estado Novo regime, and the country turned against supporting the long and draining colonial war in Mozambique. Portugal and FRELIMO negotiated Mozambique's independence, which was official in June 1975.

FRELIMO established a one-party state based on Marxist principles, with Samora Machel as President. The new government first received diplomatic recognition and some military support from Cuba and the Soviet Union. Marcelino dos Santos became vice-president.

In a suppression of the opposition, government forces quickly arrested and executed without trial Uria Simango and his wife Celina, and other prominent Frelimo dissidents, including Paulo Gumane and Adelino Gwambe, former leaders of UDENAMO.[5]

Civil War (1976-1992)

Mozambique's national anthem from 1975 to 1992 was Viva, Viva a FRELIMO ("Long Live FRELIMO").

All elements of society did not accept the new government, and a strong insurgency arose. The new government engaged in a lengthy civil war with an anti-Communist political faction known as Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO). RENAMO received support from the white-minority governments of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and apartheid South Africa.

After Machel died in 1986 in a suspicious airplane crash, Joaquim Chissano took over leadership of both the party and the state. Especially after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989 and related changes among Eastern Bloc European countries, Chissano began to envision a multi-party system in Mozambique.

This civil war conflict was not ended until 1992 under the Rome General Peace Accords. The long years of war had caused extensive social disruption and poverty, making it difficult for the government to achieve social goals and improve the lot of the people. In later years, as FRELIMO moved toward social democratic views, it received active support from Margaret Thatcher's government in the United Kingdom. Mozambique became a member of the Commonwealth of Nations, comprising mostly independent, former British colonies, including some in Africa.

End of Marxist ideology

Despite having formerly been inspired by Communist bloc countries, Chissano was not a hard-line Marxist. Following the collapse of the Eastern Bloc in 1989, he came to see Marxist ideology as outdated for the contemporary world.

He supported a revised Constitution which was adopted in 1990 and introduced the multi-party system to Mozambique. It ended one-party rule. After the Mozambican Civil War (1976–1992) was ended by the Rome General Peace Accords, the Mozambican ruling regime called for democratic, multi-party elections in 1994.

FRELIMO won the first elections with a large majority of the votes. The party believed it needed to reduce all trace of socialist influence, and its members have worked to revise official histories of the Mozambican War of Independence. Already heavily mythologized, the official history of the struggle for independence has been distorted in a new way.[6]

1999 and 2000s

At the elections in late 1999, President Chissano was re-elected with 52.3% of the vote, and FRELIMO secured 133 of 250 parliamentary seats. Due to accusations of election fraud and several cases of corruption, Chissano's government was widely criticized. But, under Chissano's leadership, Mozambique has continued to be regarded as a model of fast and sustainable economic growth and democratic changes. Chissano decided freely not to stand for the 2004 presidential election, although the constitution permitted him to do so.

In 2002, during its VIII Congress, the party selected Armando Guebuza as its candidate for the presidential election held on December 1–2, 2004. As expected given FRELIMO's majority status, he won, gaining about 60% of the vote. At the legislative elections of the same date, the party won 62.0% of the popular vote and 160 of 250 seats in the national assembly.

RENAMO and some other opposition parties made claims of election fraud and denounced the result. International observers (among others, members of the European Union Election Observation Mission to Mozambique and the Carter Center) supported these claims, criticizing the National Electoral Commission (CNE) for failing to conduct fair and transparent elections. They listed numerous cases of improper conduct by the electoral authorities that benefited FRELIMO. However, the EU observers concluded that the elections shortcomings probably did not affect the presidential election's final result.

Foreign support

FRELIMO has received support from the governments of Tanzania, Algeria, Ghana, Zambia, Libya, Sweden,[7] Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Brazil, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Cuba, China, the Soviet Union, Egypt and SFR Yugoslavia,[8] Somalia.[9]

Mozambican presidents representing FRELIMO

- Samora Machel: 25 June 1975 - 19 October 1986

- Joaquim Chissano: 6 November 1986 - 2 February 2005

- Armando Guebuza: 2 February 2005 - 15 January 2015

- Filipe Nyusi: 15 January 2015 - present

Other prominent members

- José Ibraimo Abudo, Justice minister since 1994

- Basilio Muhate, Chairman of FRELIMO Youth Organization since 2010

- Sharfudine Khan, Ambassador of Mozambique (After Liberation)

Parliament (Assembly of the republic)

| Election year | #of votes |

% of votes |

#of seats won | +/− | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 2,115,793 | 44.3 | 129 / 250 |

|

|

| 1999 | 2,005,713 | 48.5 | 133 / 250 |

|

|

| 2004 | 1,889,054 | 62.0 | 160 / 250 |

|

|

| 2009 | 2,907,335 | 74.7 | 191 / 250 |

|

|

| 2014 | 2,575,995 | 55.9 | 144 / 250 |

|

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Dar-es-Salaam once a home for revolutionaries". sundayworld.co.za. 29 April 2014. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

- ↑ Simões Reis, Guilherme (8 July 2012). "The Political-Ideological Path of Frelimo in Mozambique, from 1962 to 2012" (PDF). ipsa.org. p. 9.

- ↑ "Election of Frelimo Candidate Goes Into the Night". Mozambique News Agency. 1 March 2014. Retrieved 2014-06-09.

- ↑ Martin Rupiya, "Historical context: War and Peace in Mozambique", Conciliation Resources, php

- ↑ J. Cabrita, Mozambique: A Tortuous Road to Democracy, New York: Macmillan, 2001. ISBN 978-0-333-92001-5

- ↑ Alice Dinerman, "Independence redux in postsocialist Mozambique" Archived April 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine., IPRI

- ↑ Rui Mateus, In Contos Proibidos (p. 41)

- ↑ University of Michigan. Southern Africa: The Escalation of a Conflict, 1976, p. 99

- ↑ FRELIMO. Departamento de Informação e Propaganda, Mozambique revolution, Page 10

Further reading

- Basto, Maria-Benedita, "Writing a Nation or Writing a Culture? Frelimo and Nationalism During the Mozambican Liberation War" in Eric Morier-Genoud (ed.) Sure Road? Nationalisms in Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique (Leiden: Brill, 2012).

- Bowen, Merle. The State Against the Peasantry: Rural Struggles in Colonial and Postcolonial Mozambique. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press Of Virginia, 2000.

- Derluguian, Georgi, "The Social Origins of Good and Bad Governance: Re-interpreting the 1968 Schism in Frelimo" in Eric Morier-Genoud (ed.) Sure Road? Nationalisms in Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique (Leiden: Brill, 2012).

- Morier-Genoud, Eric, “Mozambique since 1989: Shaping democracy after Socialism” in A.R.Mustapha & L.Whitfield (eds), Turning Points in African Democracy (Oxford: James Currey, 2009), pp. 153–166

- Opello, Walter C. "Pluralism and elite conflict in an independence movement: FRELIMO in the 1960s", Journal of Southern African Studies, Volume 2, Issue 1, 1975

- Simpson, Mark, "Foreign and Domestic Factors in the Transformation of Frelimo", Journal of Modern African Studies, Volume 31, no.02, June 1993, pp 309–337

- Sumich, Jason, "The Party and the State: Frelimo and Social Stratification in Post-socialist Mozambique", Development and Change, Volume 41, no. 4, July 2010, pp. 679–698

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to FRELIMO. |

- FRELIMO official site

- Special Report on Mozambique 2004 Elections, Carter Center]

- Final Report of the European Union Election Observation Mission, 2004