Mother Goose

The figure of Mother Goose is the imaginary author of a collection of fairy tales and nursery rhymes[1] often published as (Old) Mother Goose's Rhymes. As a character, she appears in one nursery rhyme.[2] A Christmas pantomime called Mother Goose is often performed in the United Kingdom. The so-called "Mother Goose" rhymes and stories have formed the basis for many classic British pantomimes. Mother Goose is generally depicted in literature and book illustration as an elderly country woman in a tall hat and shawl, a costume identical to the peasant costume worn in Wales in the early 20th century, but is sometimes depicted as a goose (usually wearing a bonnet).

Identity

Mother Goose is the name given to an archetypal country woman. She is credited with the Mother Goose stories and rhymes popularized in the 17th century in English-language literature, although no specific writer has ever been identified with such a name.

17th-century English readers would have been familiar with Mother Hubbard, a stock figure when Edmund Spenser published the satire Mother Hubberd's Tale in 1590, as well as with similar fairy tales told by "Mother Bunch" (the pseudonym of Madame d'Aulnoy) in the 1690s.[3] An early mention appears in an aside in a versified French chronicle of weekly events, Jean Loret's La Muse Historique, collected in 1650.[4] His remark, comme un conte de la Mère Oye ("like a Mother Goose story") shows that the term was readily understood. Additional 17th-century Mother Goose/Mere l'Oye references appear in French literature in the 1620s and 1630s.[5][6][7]

In "The Real Personages of Mother Goose" (1930), Katherine Elwes-Thomas submits that the image and name "Mother Goose" or "Mère l'Oye" may be based upon ancient legends of the wife of King Robert II of France, known as "Berthe la fileuse" ("Bertha the Spinner") or Berthe pied d'oie ("Goose-Foot Bertha" ), who, according to Elwes-Thomas, is often described in French legends as spinning incredible tales that enraptured children.

Despite evidence to the contrary,[8] there are reports, familiar to tourists in Boston, Massachusetts, that the original Mother Goose was a Bostonian wife of an Isaac Goose, either named Elizabeth Foster Goose (1665–1758) or Mary Goose (d. 1690, age 42) who is interred at the Granary Burying Ground on Tremont Street.[9] According to Eleanor Early, a Boston travel and history writer of the 1930s, and 1940s, the original Mother Goose was a real person who lived in Boston in the 1660s.[10] She was reportedly the second wife of Isaac Goose (alternatively named Vergoose or Vertigoose), who brought to the marriage six children of her own to add to Isaac's ten.[11] After Isaac died, Elizabeth went to live with her eldest daughter, who had married Thomas Fleet, a publisher who lived on Pudding Lane (now Devonshire Street). According to Early, "Mother Goose" used to sing songs and ditties to her grandchildren all day, and other children swarmed to hear them. Finally, her son-in-law gathered her jingles together and printed them.[12]

Another authority on the Mother Goose tradition, Iona Opie, does not give any credence to either the Elwes-Thomas or the Boston suppositions.

Perrault's Tales of My Mother Goose

Charles Perrault, the initiator of the literary fairy tale genre, published a collection of fairy tales in 1695 called Histoires ou contes du temps passés, avec des moralités under the name of his son, which became better known under its subtitle of Contes de ma mère l'Oye or Tales of My Mother Goose. Perrault's publication marks the first authenticated starting-point for Mother Goose stories.

In 1729, an English translation appeared of Perrault's collection, Robert Samber's Histories or Tales of Past Times, Told by Mother Goose,[13] which introduced Sleeping Beauty, Little Red Riding Hood, Puss in Boots, Cinderella, and other Perrault tales to English-speaking audiences. These were fairy tales.

The first public appearance of the Mother Goose stories in the New World was in Worcester, Massachusetts, where printer Isaiah Thomas reprinted Samber's volume under the same title in 1786.[14]

Mother Goose as nursery rhymes

John Newbery was once believed to have published a compilation of English nursery rhymes entitled Mother Goose's Melody, or, Sonnets for the cradle[15] some time in the 1760s, but the first edition was probably published in 1780 or 1781 by Thomas Carnan, one of Newbery's successors. This edition was registered with the Stationers' Company in 1780. However, no copy has been traced, and the earliest surviving edition is dated 1784.[16] The name "Mother Goose" has been associated in the English-speaking world with children's poetry ever since.[17]

In 1837, John Bellenden Ker Gawler published a book (with a 2nd-volume sequel in 1840) deriving the origin of the Mother Goose rhymes from Flemish ('Low Dutch') puns.[18]

In music, Maurice Ravel wrote Ma mère l'oye, a suite for the piano, which he then orchestrated for a ballet. There is also a song called "Mother Goose" by progressive rock band Jethro Tull from their 1971 Aqualung album. The song seems to be unrelated to the figure of Mother Goose, since she is only the first of many surreal images that the narrator encounters and describes through the lyrics.

"Old Mother Goose"

In addition to being the purported author of nursery rhymes, Mother Goose is herself the title character of one such rhyme:

Old Mother Goose,

When she wanted to wander,

Would ride through the air

On a very fine gander.

Jack's mother came in,

And caught the goose soon,

And mounting its back,

Flew up to the moon.[1]

- ^ I. Opie and P. Opie, The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1951, 2nd edn., 1997), pp. 88–90.

Pantomime

Ryoji Tsurumi has shown that the transition from a shadowy generic figure to one with such concrete actions was effected at a pantomime Harlequin and Mother Goose: or, The Golden Egg in 1806–07.[19] The pantomime was first performed at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane on 29 December, and many times repeated in the new year. Harlequin and Mother Goose: or, The Golden Egg, starred the famous clown Joseph Grimaldi and was written by Thomas Dibdin, who invented the actions suitable for a Mother Goose brought to the stage and recreated her as a witch-figure, Tsurumi notes. In the first scene, the stage directions show her raising a storm and, for the very first time, flying a gander. The magical Mother Goose transformed the old miser into Pantaloon of the commedia dell'arte and the British pantomime tradition, and the young lovers Colin and Colinette into Harlequin and Columbine. She was played en travesti by Samuel Simmons[20] – a pantomime tradition that survives today – and she also raises a ghost in a macabre churchyard scene.

New Year's Tradition

Some families in Utah give their children gifts from Mother Goose on New Year's Eve.[21][22]

Other examples

- Books by L. Frank Baum and illustrator W.W. Denslow in the late 1890s featured Mother Goose and Father Goose.

- The Complete Mother Goose : nursery rhymes old and new, fully annotated edition by Daryl Leyland, with chapter decorations and illustrations by Max Van Doren, Wellman & Chaney publisher, 1938.

- Tales of Brother Goose by Brett Nicholas Moore, a book of short stories published in 2006, satirizes Mother Goose stories with modern dialogue and cynical humor.

Adaptations

There have been numerous adaptations of Mother Goose with the classic nursery rhymes and adaptations with a distinct motif including:

Literature

- Mother Goose in Prose by L. Frank Baum (1897)

- The Space Child's Mother Goose by Frederick Winsor (1958), Mother Goose for scientific children.

- The Inner City Mother Goose by Eve Merriam (1969), Urban Mother Goose.

- Black Mother Goose Book by Elizabeth Murphy Oliver (1969), Ethnic Mother Goose.

- Christian Mother Goose by Marjorie Ainsborough Decker (1978), Mother Goose gets religion.

- The Random House Book of Mother Goose by Arnold Lobel (1986), over 300 nursery rhymes

- The Alaska Mother Goose: North Country Nursery Rhymes by Shelley Gill (1987)

- New Adventures Of Mother Goose by Bruce Lansky (1993), Mother Goose with the violence abridged.

- My Very First Mother Goose by Iona Opie (1996), 68 nursery rhymes

- Tutu Nene: The Hawaiian Mother Goose Rhymes by Debra Ryll (1997)

- An Appalachian Mother Goose by James Still (1998)

- Here Comes Mother Goose by Iona Opie (1999), 56 nursery rhymes

- Monster Goose by Judy Sierra illustrated by Jack E. Davis (2001)

- Mother Goose Tells the Truth About Middle Age by Sydney Altman (2002), Mother Goose for baby boomers.

- You Read to Me, I'll Read to You by Mary Ann Hoberman (2005)

- Texas Mother Goose by David Davis (2006)

- Mother Goose's Little Treasures by Iona Opie (2007), 22 nursery rhymes

- Mother Osprey: Nursery Rhymes for Buoys & Gulls by Lucy A. Nolan illustrated by Connie McLennan (2009)

- Deep in the Desert by Rhonda Lucas Donald, illustrated by Sherry Neidigh (2011)

Other

- Mother Goose and her Fabulous Puppet Friends by Diane Ligon

- Mother Goose Nursery Rhymes Texas Style by Vicki Nichols

- Nursery Rhymes by Mother Mouse: Mother Goose in the computer nursery.

- Nursery Rhymes Old and New: Mother Goose meets Mother Mouse face to face.

- Mother Goose Rhymes, 1938 WPA mural by Elba Lightfoot at Harlem Hospital, New York, NY

- Mother Goosed – Brighton Gay Panto, by the Pure Corn Company 2010.

- Nursery Rhymes with Storytime by Atomic Antelope (co-produced by ustwo Ltd.) 2011.

- Panto Mother Goose, book & lyrics by Kenn McLaughlin, music by David Nehls, Houston, TX Pantomime, 2012

See also

- List of children's songs

- List of children's stories

- Luis van Rooten, Mots d'Heures: Gousses, Rames (1967).

- Mother Goose and Grimm, a comic strip

Notes

- ↑ Macmillan Dictionary for Students Macmillan, Pan Ltd. (1981), page 663. Retrieved 2010-7-15.

- ↑ Margaret Lima Norgaard, "Mother Goose", Encyclopedia Americana 1987; see, for instance, Peter and Iona Opie, The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (1951) 1989.

- ↑ Ryoji Tsurumi, "The Development of Mother Goose in Britain in the Nineteenth Century" Folklore 101.1 (1990:28–35) p. 330 instances these, as well as the "Mother Carey" of sailor lore— "Mother Carey's chicken" being the European storm-petrel— and the Tudor period prophetess "Mother Shipton".

- ↑ Shahed, Syed Mohammad (1995). "A Common Nomenclature for Traditional Rhymes". Asian Folklore Studies. 54 (2): 307–314. JSTOR 1178946.

- ↑ Les satyres de Saint-Regnier – ... Saint-Regnier – Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ De la nature, vertu et utilité des plantes – Guido de Labrosse – Google Boeken. Books.google.com. 21 September 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ Pičces curieuses en suite de celles du Sieur de St. Germain – Google Boeken. Books.google.com. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ For, Written (4 February 1899). "MOTHER GOOSE. - Longevity of the Boston Myth - The Facts of History in this Matter. - Review - NYTimes.com". New York Times. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ "Listed as "Elizabeth" but the grave marker is distinctly inscribed "Mary Goose"". Findagrave.com. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ [ Displaying Abstract ] (20 October 1886). "MOTHER GOOSE. - Article - NYTimes.com". New York Times. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ Wilson, Susan. Literary Trail of Greater Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000: 23. ISBN 0-618-05013-2

- ↑ Reader's Digest April 1939:28.

- ↑ Reprinted, Garland Publishing Co., 1977.

- ↑ Charles Francis Potter, Mother Goose, Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology, and Legends II (1950), p. 751f.

- ↑ "Mother Goose's melody : Prideaux, William Francis, 1840–1914 : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". Archive.org. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ Nigel Tattersfield in Mother Goose's melody ... (a facsimile of an edition of c. 1795, Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2003).

- ↑ Driscoll, Michael; Hamilton, Meredith; Coons, Marie (2003). A Child's Introduction Poetry. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 1-57912-282-5.

- ↑ Shilling, Jane (20 May 2005). The Sunday Times http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/article524173.ece?token=null&offset=12&page=2. Retrieved 26 September 2010. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Tsurumi 1990:28–35.

- ↑ Tsurumi (1990:30) notes that Simmon's "Mother Goose" was memorialised at the time in a popular engraving.

- ↑ Batchelor, Laurel. "8.1.2.12.2" (October 1989). Collection of Customs, ID: FA 14 Series 8 Subseries 1 8.1.2.12.2. Provo, Utah: L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

- ↑ Breinholdt, Dianne. "8.1.2.13.1" (1987). Collection of Customs, ID: FA 14 Series 8 Subseries 1 8.1.2.13.1. Provo, Utah: L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mother Goose |

- 1904 Facsimile of earliest American compilation, John Newberry's Mother Goose's Melody, 1791 edition

- "Who was Mother goose?"

- The Real Mother Goose

- At Project Gutenberg:

- The Tales of Mother Goose by Charles Perrault translated by Charles Welsh

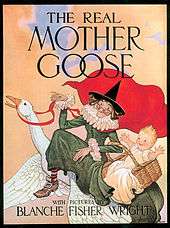

- The Real Mother Goose illustrated by Blanche Fisher Wright

- The Only True Mother Goose Melodies (Anonymous)

- Mother Goose in Prose by L. Frank Baum

-

Mother Goose public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Mother Goose public domain audiobook at LibriVox - Mother Goose Clip Art Public domain illustrations of Mother Goose rhymes

- Collection of Mother Goose verses

- Verses with artwork and audio recordings

- Play and education with Mother Goose nursery rhymes

- Earliest extant evidence of an American Mother Goose in 1691

- Illustrated Editions of Traditional Mother Goose Rhymes: A Bibliographical Listing