Mormon Trail

| Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail | |

|---|---|

|

Echo Canyon, Utah on Mormon Trail | |

| Location | Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah, US |

| Nearest city | Nauvoo, Illinois ; Salt Lake City, Utah |

| Established | November 10, 1978 |

| Governing body | National Trails System |

| Website |

www |

The Mormon Trail is the 1,300-mile (2,092 km) route that members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints traveled from 1846 to 1868. Today, the Mormon Trail is a part of the United States National Trails System, known as the Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail.

The Mormon Trail extends from Nauvoo, Illinois, which was the principal settlement of the Latter Day Saints from 1839 to 1846, to Salt Lake City, Utah, which was settled by Brigham Young and his followers beginning in 1847. From Council Bluffs, Iowa to Fort Bridger in Wyoming, the trail follows much the same route as the Oregon Trail and the California Trail; these trails are collectively known as the Emigrant Trail.

The Mormon pioneer run began in 1846, when Young and his followers were driven from Nauvoo. After leaving, they aimed to establish a new home for the church in the Great Basin and crossed Iowa. Along their way, some were assigned to establish settlements and to plant and harvest crops for later emigrants. During the winter of 1846–47, the emigrants wintered in Iowa, other nearby states, and the unorganized territory that later became Nebraska, with the largest group residing in Winter Quarters, Nebraska. In the spring of 1847, Young led the vanguard company to the Salt Lake Valley, which was then outside the boundaries of the United States and later became Utah.

During the first few years, the emigrants were mostly former occupants of Nauvoo who were following Young to Utah. Later, the emigrants increasingly comprised converts from the British Isles and Europe.

The trail was used for more than 20 years, until the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. Among the emigrants were the Mormon handcart pioneers of 1856–60. Two of the handcart companies, led by James G. Willie and Edward Martin, met disaster on the trail when they departed late and were caught by heavy snowstorms in Wyoming.

Background

Under the leadership of Joseph Smith, Latter Day Saints established several communities throughout the United States between 1830 and 1844, most notably in Kirtland, Ohio; Independence, Missouri; and Nauvoo. However, the Saints were driven out of each of them in turn, due to conflicts with other settlers (see History of the Latter Day Saint movement). This included the actions of Governor Lilburn Boggs, who issued Missouri Executive Order 44, which called for the "extermination" of all Mormons in Missouri. Latter-day Saints were finally forced to abandon Nauvoo in 1846.[1]

Although the movement had split into several denominations after Smith's death in 1844, most members aligned themselves with Brigham Young and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS). Under Young's leadership, about 14,000 Mormon citizens of Nauvoo set out to find a new home in the West.[2]

The Trek West

As the senior apostle of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles after Joseph Smith's death, Brigham Young assumed responsibility of the leadership of the church. He would later be sustained as President of the Church and prophet.[3]

Young now had to lead the Saints into the far west, without knowing exactly where to go or where they would end up. He insisted the Mormons should settle in a place no one else wanted and felt the isolated Great Basin would provide the Saints with many advantages.[4]

Young reviewed information on the Great Salt Lake Valley and the Great Basin, consulted with mountain men and trappers, and met with Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, a Jesuit missionary familiar with the region. Young also organized a vanguard company to break trail to the Rocky Mountains, evaluate trail conditions, find sources of water, and select a central gathering point in the Great Basin. A new route on the north side of the Platte and North Platte rivers was chosen to avoid potential conflicts over grazing rights, water access, and campsites with travelers using the established Oregon Trail on the river’s south side.

The Quincy Convention of October 1845 passed resolutions demanding that the Latter-day Saints withdraw from Nauvoo by May 1846. A few days later, the Carthage Convention called for establishment of a militia that would force them out if they failed to meet the May deadline.[5] To try to meet this deadline and to get an early start on the trek to the Great Basin, the Latter-day Saints began leaving Nauvoo in February 1846.[6]

Trek of 1846

The departure from Nauvoo began on February 4, 1846, under the leadership of Brigham Young. This early departure exposed them to the elements in the worst of winter. After crossing the Mississippi River, the journey across Iowa Territory followed primitive territorial roads and Native American trails.

Young originally planned to lead an express company of about 300 men to the Great Basin during the summer of 1846. He believed they could cross Iowa and reach the Missouri River in four to six weeks. However, the actual trip across Iowa was slowed by rain, mud, swollen rivers, and poor preparation, and it required 16 weeks – nearly three times longer than planned.

Heavy rains turned the rolling plains of southern Iowa into a quagmire of axle-deep mud. Furthermore, few people carried adequate provisions for the trip. The weather, general unpreparedness, and lack of experience in moving such a large group of people all contributed to the difficulties they endured.

The initial party reached the Missouri River on June 14. It was apparent that the Latter-day Saints could not make it to the Great Basin that season and would have to winter on the Missouri River..[7]

Some of the emigrants established a settlement called Kanesville on the Iowa side of the river. Others moved across the river into the area of present-day Omaha, Nebraska, and built a camp called Winter Quarters.[8]

The Vanguard Company of 1847

In April 1847, chosen members of the vanguard company gathered, final supplies were packed, and the group was organized into 14 military companies. A militia and night guard were formed. The company consisted of 143 men, including three blacks and eight members of the Quorum of the Twelve, three women, and two children. The train contained 73 wagons, draft animals, and livestock, and carried enough supplies to provision the group for one year. On April 5, the wagon train moved west from Winter Quarters toward the Great Basin.[9]

The journey from Winter Quarters to Fort Laramie took six weeks; the company arrived at the fort on June 1. While at Fort Laramie, the vanguard company was joined by members of the Mormon Battalion, who had been excused due to illness and sent to winter in Pueblo, Colorado, and a group of Church members from Mississippi. At this point, the now larger company took the established Oregon Trail toward the trading post at Fort Bridger.[2][10]

Young met mountain man Jim Bridger on June 28. They discussed routes into the Salt Lake Valley and the feasibility of viable settlements in the mountain valleys of the Great Basin. The company pushed on through South Pass, rafted across the Green River, and arrived at Fort Bridger on July 7. About the same time, they were joined by 12 more members of the sick detachment of the Mormon Battalion.[2][9]

Now facing a more rugged and hazardous trek, Young chose to follow the trail used by the Donner–Reed party on their journey to California the previous year. As the vanguard company traveled through the rugged mountains, they divided into three sections. Young and several other members of the party suffered from a fever, generally accepted as a “mountain fever” induced by wood ticks. The small sick detachment lagged behind the larger group, and a scouting division was created to move farther ahead on the designated route.[2]

Scouts Erastus Snow and Orson Pratt entered the Salt Lake Valley on July 21. On July 23, Pratt offered a prayer dedicating the land to the Lord. Ground was broken, irrigation ditches were dug, and the first fields of potatoes and turnips were planted. On July 24, Young first saw the valley from a “sick” wagon driven by his friend Wilford Woodruff. According to Woodruff, Young expressed his satisfaction in the appearance of the valley and declared, "This is the right place, drive on."[2][11]

In August 1847, Young and selected members of the vanguard company returned to Winter Quarters to organize the companies scheduled for following years. By December 1847, more than 2,000 Mormons had completed the journey to the Salt Lake Valley, then in Mexican territory.[2][12]

Farming the uncultivated land was initially difficult, as the shares broke when they tried to plow the dry ground. Therefore, an irrigation system was designed and the land was flooded before plowing, and the resulting system provided supplemental moisture during the year.

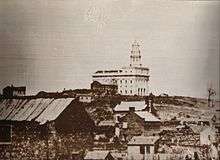

Salt Lake City was laid out and designated as Church headquarters. Hard work produced a prosperous community. In their new settlement, entertainment was also important, and the first public building was a theater.

It did not take long, however, until the United States caught up with them, and in 1848, after the end of the war with Mexico, the land in which they settled became part of the United States.[13]

Ongoing migration

Each year during the Mormon migration, people continued to be organized into "companies", each company bearing the name of its leader and subdivided into groups of 10 and 50. The Saints traveled the trail broken by the vanguard company, splitting the journey into two sections. The first segment began in Nauvoo and ended in Winter Quarters, near modern-day Omaha, Nebraska. The second half of the journey took the Saints through the area that later became Nebraska and Wyoming, before finishing their journey in the Salt Lake Valley in present-day Utah. The earlier groups used covered wagons pulled by oxen to carry their supplies across the country. Some later companies used handcarts and traveled by foot.[2]

By 1849, many of the Latter-day Saints who remained in Iowa or Missouri were poor and unable to afford the costs of the wagon, teams of oxen, and supplies that would be required for the trip. Therefore, the LDS Church established a revolving fund, known as the Perpetual Emigration Fund, to enable the poor to emigrate. By 1852, most of the Latter-day Saints from Nauvoo who wished to emigrate had done so, and the church abandoned its settlements in Iowa. However, many church members from the eastern states and from Europe continued to emigrate to Utah, often assisted by the Perpetual Emigration Fund.[14]

Handcarts: 1856–60

In 1856, the church inaugurated a system of handcart companies in order to enable poor European emigrants to make the trek more cheaply. Handcarts, two-wheeled carts that were pulled by emigrants instead of draft animals, were sometimes used as an alternate means of transportation from 1856 to 1860. They were seen as a faster, easier, and cheaper way to bring European converts to Salt Lake City. Almost 3,000 Mormons, with 653 carts and 50 supply wagons, traveling in 10 different companies, made the trip over the trail to Salt Lake City. While not the first to use handcarts, they were the only group to use them extensively.[15]

The handcarts were modeled after carts used by street sweepers and were made almost entirely of wood. They were generally six to seven feet (183 to 213 cm) long, wide enough to span a narrow wagon track, and could be alternately pushed or pulled. The small boxes affixed to the carts were three to four feet (91 to 122 cm) long and eight inches (20 cm) high. They could carry about 500 pounds (227 kg), most of this weight consisting of trail provisions and a few personal possessions.[16]

All but two of the handcart companies successfully completed the rugged journey, with relatively few problems and only a few deaths. However, the fourth and fifth companies, known as the Willie and Martin Companies, respectively, had serious problems. The companies left Iowa City, Iowa, in July 1856, very late to begin the trip across the plains. They met severe winter weather west of present-day Casper, Wyoming, and continued to cope with deep snow and storms for the remainder of the journey. Food supplies were soon exhausted. Young organized a rescue effort that brought the companies in, but more than 210 of the 980 emigrants in the two parties died.[17]

The handcart companies continued with more success until 1860, and traditional ox-and-wagon companies also continued for those who could afford the higher cost. After 1860, the church began sending wagon companies east each spring, to return to Utah in the summer with the emigrating Latter-day Saints. Finally, with the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, future emigrants were able to travel by rail, and the era of the Mormon pioneer trail came to an end.[18]

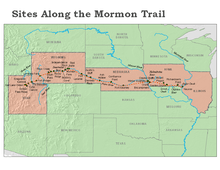

Sites along the trail

The following are major points along the trail at which the early Mormon pioneers stopped, established temporary camps, or used as landmarks and meeting places. The sites are categorized by their location in respect to modern-day US states.

Illinois

- Nauvoo — Nauvoo was the starting point for the Mormon trail and the early home base for LDS migrants. They left because they were treated poorly by those whom lived there. Brigham Young took a group of people through Illinois to Utah, not part of the United States

Iowa

- Sugar Creek (7 miles (11 km) west of Nauvoo) — Beginning with their first ferry crossing of the Mississippi River on February 4, 1846, months before many of them were ready, the Latter-day Saints started gathering at the frozen banks of Sugar Creek. More refugees continued to cross into Iowa for a number of months many taking advantage of the freezing of the Mississippi river a few weeks later. The poorly prepared emigrants suffered from severe winter weather while camped there. Sugar Creek was the staging area for the westward trek across Iowa. Ultimately about 2,500 refugees and 500 wagons started west on March 1, 1846. Several thousand more would follow on later as they sold their property for what they could get and continued to leave Nauvoo, Illinois.[19][20]

- Richardson's Point (35 miles (56 km) west) — The emigrants made their way past Croton and Farmington to ford the Des Moines River at Bonaparte. In early March 1846 the party was halted for 10 days by heavy rain at a wooded area known as Richardson's Point. Some of the first deaths of the pioneers occurred at this location.[21]

- Chariton River Crossing (80 miles (129 km) west) — The trail continues past the modern towns of Troy, Drakesville, and West Grove to reach the Chariton River. At this crossing, on March 27, Young organized the lead group of the migration, forming three camps of 100 families, each led by a captain. This military-style organization would be used for all subsequent Mormon emigrant companies.[22]

- Locust Creek (103 miles (166 km) west) — The trail proceeds past Cincinnati to Locust Creek. There on April 13 William Clayton, scribe for Brigham Young, composed "Come, Come Ye Saints," the most famous and enduring hymn from the Mormon Trail.[19][23]

- Garden Grove (128 miles (206 km) west) — On April 23 the emigrants arrived at the location of their first semi-permanent settlement, which they named Garden Grove. They enclosed and planted 715 acres (2.89 km2) to supply food for later emigrants and established a village that is still in existence today. About 600 Latter-day Saints settled at Garden Grove. By 1852 they had moved on to Utah.[2][19]

- Mount Pisgah (153 miles (246 km) west) — As they entered Potawatomi territory, the emigrants established another semi-permanent settlement that they named Mount Pisgah. Several thousand acres were cultivated and a settlement of about 700 Latter-day Saints thrived there from 1846 to 1852. Now the site is marked by a 9-acre (36,000 m2) park, which contains exhibits, historical markers, and a reconstructed log cabin. However, little remains from the 19th century except a cemetery memorializing the 300 to 800 emigrants who died there.[2][24]

- Nishnabotna River Crossing (232 miles (373 km) west) — From Mount Pisgah the trail proceeds past the modern towns of Orient, Bridgewater, Massena and Lewis. Just west of Lewis, the 1846 emigrants passed a Potawatomi encampment on the Nishnabotna River. The Potawatomis were also refugees; 1846 was their last year in the area.[25][26]

- Grand Encampment (255 miles (410 km) west) — From the Nishnabotna River, the trail proceeds past present-day Macedonia to Mosquito Creek on the eastern outskirts of present-day Council Bluffs. The first emigrant company arrived on June 13, 1846. At this open area, where the Iowa School for the Deaf is now located, the LDS emigrant companies paused and camped, forming what was called the Grand Encampment. From this site on July 20, the Mormon Battalion departed for the Mexican-American War.[25][27]

- Kanesville (later Council Bluffs) (265 miles (426 km) west) — The emigrants established an important settlement and outfitting point at this site on the Missouri River, originally known as Miller's Hollow. The emigrants renamed the settlement as Kanesville, honoring Thomas L. Kane, a non-LDS attorney who was politically well connected and used his influence to assist the Latter-day Saints. From 1846 to 1852, it was an important LDS settlement and the outfitting point for companies traveling to present-day Utah. Orson Hyde, an Apostle and ecclesiastical leader of the settlement, published a newspaper called the Frontier Guardian. In 1852 the major LDS settlements at Kanesville, Mount Pisgah, and Garden Grove were closed as the settlers moved on to Utah. After 1852, however, the Church continued to outfit and supply emigrant companies (mostly LDS converts coming from the British Isles and mainland Europe) at this community, now renamed Council Bluffs, until the mid-1860s, when the terminus of the First Transcontinental Railroad was extended to the west.[2][28][29]

Nebraska

- Winter Quarters (266 miles (428 km) west) — Although Brigham Young had originally planned to travel all the way to the Salt Lake Valley in 1846, the emigrants' lack of preparation had become apparent during their difficult crossing of Iowa. Furthermore, the departure of the Mormon Battalion left the emigrants short on manpower. Young decided to settle for the winter along the Missouri River. The emigrants were located on both sides of the river, but their settlement at Winter Quarters on the west side was the largest. There they built 700 dwellings where an estimated 3,500 Latter-day Saints spent the winter of 1846–47; many would also reside there during the winter of 1847–48. Conditions such as scurvy, consumption, chills and fever were common; the settlement recorded 359 deaths between September 1846 and May 1848. However, while at Winter Quarters the LDS emigrants were able to save or trade for the equipment and supplies that they would need to continue the westward trek. The settlement was later renamed Florence and is now located in Omaha.[30]

- Elkhorn River (293 miles (472 km) west)

- Platte River (305 miles (491 km) west) — All emigrants leaving Missouri traveled along the Great Platte River Road for hundreds of miles. There was a prevailing opinion that the North side of the river was healthier, so most Latter-day Saints generally stuck to that side, which also separated them from unpleasant encounters with potential former enemies, like emigrants from Missouri or Illinois. In 1849, 1850 & 1852, traffic was so heavy along the Platte that virtually all feed was stripped from both sides of the river. The lack of food and the threat of disease made the journey along the Platte a deadly gamble.[31]

- Loup Fork (352 miles (566 km) west) — Crossing the Loup Fork was, like the Elkhorn, one of the early and very difficult crossings during the trek west from Council Bluffs.[32]

- Fort Kearny (469 miles (755 km) west) — This fort, named after Stephen Watts Kearny, was established in June 1848. Another fort named after Kearny was established in May 1846, but was abandoned in May 1848. Due to this, the second Fort Kearny is sometimes called New Fort Kearny. The site for the fort was purchased from the Pawnee Indians for $2,000 in goods.[33]

- Confluence Point (563 miles (906 km) west) — On May 11, 1847, three-fourths of a mile north of the confluence of the North and South Platte Rivers, a "roadometer" was attached to Heber C. Kimball's wagon driven by Pilo Johnson. Although they did not invent the device, the measurements of the version they used were accurate enough to be used by William Clayton in his famous Latter-day Saints' Emigrants' Guide.[34]

- Ash Hollow (646 miles (1,040 km) west) — Many passing diarists noted the beauty of Ash Hollow, although this was ruined by thousands of passing emigrants. The Sioux Indians were often on location and were at the site and General William S. Harney's troops won a battle over the Sioux there in September 1855 — the Battle of Ash Hollow. The site is also the burial ground of many who died of cholera during the gold rush years.[35]

- Chimney Rock (718 miles (1,156 km) west) — Chimney Rock is perhaps the most significant landmark on the Mormon Trail. Emigrants commented in their diaries that the landmark appeared closer than it actually was, and many sketched or painted it in their journals and carved their names into it.[36]

- Scotts Bluff (738 miles (1,188 km) west) — Hiram Scott was a Rocky Mountain Fur Company trapper abandoned on the bluff that now bears his name by his companions when he became ill. Accounts of his death are noted by almost all those who kept journals that traveled on the north side of the Platte. The grave of Rebecca Winters, a Latter-day Saint mother who fell victim to cholera in 1852, is also located near this site, although it has since been moved and rededicated.[37]

Wyoming

- Fort Laramie (788 miles (1,268 km) west) — This old trading and military post served as a place for the emigrants to rest and restock provisions. The 1856 Willie Handcart Company was unable to obtain provisions at Fort Laramie, contributing to their subsequent tragedy when they ran out of food while encountering blizzard conditions along the Sweetwater River.[38][39]

- Upper Platte/Mormon Ferry (914 miles (1,471 km) west) — The last crossing of the Platte River took place near modern Casper. For several years the Latter-day Saints operated a commercial ferry at the site, earning revenue from the Oregon- and California-bound emigrants. The ferry was discontinued in 1853 after a competing toll bridge was constructed. On October 19, 1856, the Martin Handcart Company forded the freezing river in mid-October, leading to exposure that would prove fatal to many members of the company.[40][41]

- Red Butte (940 miles (1,513 km) west) — Red Butte was the most tragic site of the Mormon Trail. After crossing the Platte River, the Martin Handcart Company camped near Red Butte as heavy snow fell. Snow continued to fall for three days, and the company came to a halt as many emigrants died. For nine days the company remained there, while 56 persons died from cold or disease. Finally, on October 28, an advance team of three men from the Utah rescue party reached them. The rescuers encouraged them that help was on the way and urged the company to start moving on.[42]

- Sweetwater River (964 miles (1,551 km) west) — From the last crossing of the Platte, the trail heads directly southwest toward Independence Rock, where it meets and follows the Sweetwater River to South Pass. To shorten the journey by avoiding the twists and turns of the river, the trail includes nine river crossings.[43][44]

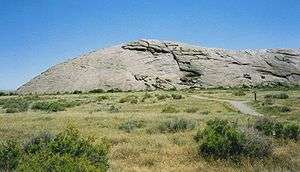

- Independence Rock (965 miles (1,553 km) west) — Independence Rock was one of the trail's best known and most anticipated landmarks. Many emigrants carved their names on the rock; many of these carvings are still visible today. The emigrants sometimes also celebrated their arrival at this landmark with a dance.[45]

- Devil's Gate (970 miles (1,561 km) west) — Devil's Gate was a narrow gorge cut through the rocks by the Sweetwater River. A small fort was located at Devil's Gate, which was unoccupied in 1856 when the Martin Handcart Company was rescued. The rescuers unloaded unnecessary equipment from the wagons so the weaker handcart emigrants could ride. A group of 19 men, led by Daniel W. Jones, stayed at the fort over the winter to protect the property.[46][47]

- Martin's Cove (993 miles (1,598 km) west) — On November 4, 1856, the Martin Handcart Company set up camp in Martin's Cove as another blizzard halted their progress. They remained there for five days until the weather abated and they could proceed toward Salt Lake City. Today, a visitor's center is located on the site.[48][49]

- Rocky Ridge (1,038 miles (1,670 km) west) — Between the fifth and sixth crossings of the Sweetwater, on October 19, 1856, the Willie Handcart Company was halted by the same snowstorm that stopped the Martin Handcart Company near Red Butte. At the same time, the members of the Willie Company reached the end of their supplies of flour. A small advance team from the rescue party found their camp and gave them a small amount of flour, but then pushed on to the east to try to locate the Martin Company. Captain James Willie and Joseph Elder went ahead through the snow to find the main rescue party and inform them of the Willie Company's peril. On October 23, with the help of the rescue party, the Willie Company pushed ahead through the biting wind and snow up Rocky Ridge, a rough 5-mile (8.0 km) section of the trail that ascends to a ridge in order to bypass a section of the Sweetwater River valley that is impassable.[50]

- Rock Creek (1,048 miles (1,687 km) west) — After their grueling 18-hour trek up Rocky Ridge, the Willie Handcart Company camped at the crossing of Rock Creek. That night 13 emigrants died; the next morning their bodies were buried in a shallow grave.[51]

- South Pass (Continental Divide) (1,065 miles (1,714 km) west) — South Pass, a 20-mile (32 km) wide pass across the Continental Divide, is located between the modern towns of Atlantic City and Farson. At an elevation of 7,550 feet (2,300 m) above sea level, it was one of the most important landmarks of the Mormon Trail. Near South Pass is Pacific Springs, which received its name because its waters ran to the Pacific Ocean.[52]

- Green River/Lombard Ferry (1,128 miles (1,815 km) west) — The trail crosses the Green River between the modern towns of Farson and Granger. The Latter-day Saints operated a ferry at this location to assist the church's emigrants and to earn money from other emigrants traveling to Oregon and California.[53]

- Ft. Bridger (1,183 miles (1,904 km) west) — Fort Bridger was established in 1842 by famous mountain man Jim Bridger. This was the site where the paths of the Oregon Trail, the California Trail, and the Mormon Trail separated; the three trails ran in parallel from Missouri River to Fort Bridger. In 1855, the LDS Church bought the fort from Jim Bridger and Louis Vazquez for $8,000. During the Utah War in 1857, the Utah militia burned down the fort so that it would not fall into the hands of the advancing U.S. Army under General A.S. Johnston.[54]

- Bear River Crossing (1,216 miles (1,957 km) west) — At this, one of the last river crossings on the Mormon Trail, Lansford Hastings and his company turned north, while the Reed–Donner Company turned south. Also at this site, the vanguard company met mountaineer Miles Goodyear on July 10, 1847, who attempted to persuade them to take the northern track toward his trading post.[55]

- The Needles (1,236 miles (1,989 km) west) — Near this very prominent rock formation, close to the Utah–Wyoming border, Brigham Young became ill with what was probably Rocky Mountain spotted fever during the advance push into the Salt Lake Valley.[56]

Utah

- Echo Canyon (1,246 miles (2,005 km) west) — One of the last canyons through which the emigrants descended, this deep and narrow canyon made it a veritable, and frequently noted, echo chamber.[57]

- Big Mountain (1,279 miles (2,058 km) west) — Although dwarfed by the surrounding Wasatch mountain peaks, this was the highest elevation of the entire Mormon trail at 8,400 feet (2560 m).[58]

- Golden Pass Road (1,281 miles (2,062 km) west) — Although unsuccessful in a petition to Salt Lake City for funding, Parley P. Pratt obtained the deed to the canyon and began the construction of a road through Big Canyon Creek in the Wasatch Mountains just south of Emigration Canyon in July 1849. The canyon became known as Parley's Canyon and the road he built as the "Golden Pass Road," due to the large number of gold miners who used it on their way to California. A cutoff was constructed through Silver Creek Canyon by 1862, diverting much of the traffic on what is today the route of I-80.[59]

- Emigration Canyon (Donner Hill) (1,283 miles (2,065 km) west) — About a year before the Latter-day Saint emigrants, the Reed–Donner wagon train carved the first road through the final geographic obstacle between Big Mountain and the Salt Lake Valley. About halfway through, the group changed course and went up and around the final constriction near the valley's mouth. The resulting exhaustingly brutal climb over rock and sage most likely contributed to the historic tragedy that befell the travelers three months and 600 miles (970 km) to the west. When an advance team from the Latter-day Saint vanguard company came through, it chose to stick to the valley floor and hacked its way through to the bench overlooking the Great Salt Lake basin in less than four hours.[60]

- Salt Lake Valley (1,297 miles (2,087 km) west) — Although the Salt Lake Valley had a special meaning to each emigrant, signifying the end of more than a year of crossing the plains, not all of the pioneering Saints settled in the Salt Lake Valley. Settlement outside the Salt Lake Valley began as early as 1848, with a number of communities planted in the Weber valley to the north. Additional townsites were carefully chosen, with settlements placed near canyon mouths with access to dependable streams and stands of timber. Latter-day Saints founded more than 600 communities from Canada down into Mexico. As historian Wallace Stegner stated, the Latter-day Saints "were one of the principal forces in the settlement of the West."[61][62]

See also

- Landmarks of the Nebraska Territory

- Mormon handcart pioneers

- Mormon Pioneer National Heritage Area

- Mormon Trail (Canada)

- Mormonism

- National Historic Trails Interpretive Center

- Martin's Cove

- Oregon-California Trails Association

- Pioneer Day in Utah on July 24

- This Is The Place Heritage Park

References

- ↑ Allen & Leonard (1976), pp. 53–222

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Hartley (1997)

- ↑ Allen & Leonard (1976), pp. 198–202, 255

- ↑ Allen & Leonard (1976), pp. 208–215

- ↑ Bennett (1997), p. 6

- ↑ Allen & Leonard (1976), pp. 222–223

- ↑ Bennett (1997), p. 31–40

- ↑ Allen & Leonard (1976), pp. 234–238, 247–248

- 1 2 Clayton, William (1921). William Clayton's Journal. Salt Lake City: Deseret News.

- ↑ Allen & Leonard (1976), p. 244

- ↑ Allen & Leonard (1976), pp. 246–247

- ↑ Allen & Leonard (1976), p. 247

- ↑ Fisher, Albert L. (1994). "Physical Geography of Utah". In Powell, Allan Kent. Utah History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Allen & Leonard (1976), pp. 279–287

- ↑ Hafen & Hafen (1992), pp. 29–34, 193–194

- ↑ Hafen & Hafen (1992), pp. 53–55

- ↑ Hafen & Hafen (1992)

- ↑ Hafen & Hafen (1992), pp. 191–192

- 1 2 3 Kimball (1979), p. 14

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Sugar Creek". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Richardson's Point". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Chariton River Crossing". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Locust Creek". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ↑ Kimball (1979), pp. 14–15

- 1 2 Kimball (1979), p. 16

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Nishnabotna River Crossing". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Grand Encampment". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ↑ Allen & Leonard (1976), pp. 247–248

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Council Bluffs". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ↑ Allen & Leonard (1976), pp. 234–238

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Platte River". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-22.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Loup Fork". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Fort Kearny". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Confluence Point". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-29.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Ash Hollow". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-30.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Chimney Rock". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-30.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Scotts Bluff". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-30.

- ↑ Hafen & Hafen (1992), p. 101

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Fort Laramie". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ Hafen & Hafen (1992), pp. 108–109

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Upper Platte (Mormon) Ferry". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ Hafen & Hafen (1992), pp. 110–115

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Sweetwater River". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ "Ninth Crossing of the Sweetwater (Burnt Ranch)". Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Independence Rock". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Devil's Gate". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ Jones, Daniel W. (1890). Forty Years Among the Indians: A True Yet Thrilling Narrative of the Author's Experiences Among the Natives. Salt Lake City, Utah: Juvenile Instructor Office.

- ↑ Hafen & Hafen (1992), pp. 132–134

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Martin's Cove". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ Bartholomew & Arrington (1981), pp. 15–18

- ↑ Bartholomew & Arrington (1981), pp. 17–18

- ↑ Kimball (1979), p. 30

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Green River". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-28.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Fort Bridger". LDS.org. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Bear River". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-31.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / The Needles". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-31.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Echo Canyon". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-31.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Big Mountain". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-31.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Golden Pass Road". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-31.

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Emigration Canyon". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-31.

- ↑ Stegner (1992), p. 7

- ↑ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Salt Lake Valley". LDS.org. Retrieved 2006-05-31.

Bibliography

- Allen, James B.; Leonard, Glen M. (1976). The Story of the Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book Company. ISBN 0877475946. OCLC 2493259.

- Bartholomew, Rebecca; Arrington, Leonard J. (1981). Rescue of the 1856 Handcart Companies. Brigham Young University, Charles Redd Center for Western Studies. ISBN 0-8425-1941-6.

- Bennett, Richard E. (October 1997). We'll Find the Place: The Mormon Exodus, 1846–1848. Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book Company. ISBN 1-57345-286-6.

- Hafen, Leroy; Hafen, Ann (May 1992). Handcarts to Zion. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-7255-3.

- Hartley, William G. (July 1997). "Gathering the Dispersed Nauvoo Saints, 1847–52". Ensign: 12–15.

- Kimball, Stanley B. (1979). Discovering Mormon Trails: New York to California, 1831–1868. Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book Company. LCCN 79053092. OCLC 5614526.

- Kimball, Stanley B. (1997). The Mormon Pioneer Trail: MTA 1997 Official Guide. Salt Lake City, Utah: Mormon Trails Association. ISBN 0-87905-263-5.

- Madsen, Carol Cornwall (1997). Journey to Zion: Voices from the Mormon Trail. Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book Company. ISBN 1-57345-244-0.

- Slaughter, William; Michael Landon (September 1997). Trail of Hope: The Story of the Mormon Trail. Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book Company. ISBN 1-57345-251-3.

- Stegner, Wallace Earl (1992). The Gathering of Zion. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-935704-12-4.

Further reading

- Jenkins, Matt (July 24, 2009). "Following the Wagon Wheels of the Latter-Day Saints". The New York Times.

- Kimball, Stanley B. (May 1991). Historic Resource Study: Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail. National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. OCLC 43406906.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mormon Trail. |

- National Park Service site on the Mormon trail

- The Mormon Pioneer Story

- Photos and history of the trail in Wyoming

- Mormon Trails Association

- National Mormon National Trail itinerary in Iowa

- Church History Library at FamilySearch Research Wiki for genealogists

- LDS Emigration and Immigration at FamilySearch Research Wiki for genealogists

- Mormon Trail at FamilySearch Research Wiki for genealogists with strategies and records for finding pioneer ancestors