Montenegrins

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 460,000[a] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| 100,000 (2014)[2] | |

| 40,000 (2014)[2] | |

| 38,527 (2011)[2] | |

| 30,000 (2001)[2] | |

| 25–30,000[2] | |

| 12,000 (2001)[2] | |

| 10,071 (1991)[3] | |

| 7,000 (2015)[4] | |

| 4,517 (2011)[5] | |

| 2,970 (2011)[6] | |

| 2,686 (2002)[7] | |

| 2,667 (2002)[8] | |

| 1,171 (2006)[9] | |

| 366 (2011)[10] | |

| Languages | |

| Montenegrin | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Eastern Orthodoxy,[11] with a Catholic and Muslim minority | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other South Slavs | |

|

a The total figure is merely a sum of all the referenced populations listed. | |

Montenegrins (Montenegrin: Црногорци/Crnogorci, pronounced [tsr̩nǒɡoːrtsi] or [tsr̩noɡǒːrtsi]), literally "People of the Black Mountain", are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Montenegro. Migrant communities exist in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, the Republic of Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey, United States, Argentina, Germany, Luxembourg, Chile, Canada, and Australia.

Identity and population

Slavs have lived in the area of Montenegro since the 6th and 7th centuries in the medieval state of Doclea. Montenegro (Montenegrin: Crna Gora) got its present name during the rule of the Crnojević dynasty. After the Christmas Uprising (1919), which saw fighting between the pro-Petrovic guerrillas and the Karadjordjevic troops, supporters of Montenegrin king Nicholas I expressed opposition to unification with Serbia because it meant total disappearance of Montenegro, their leader Krsto Zrnov Popovic wanted to unify, but under the rule of king Nicholas I. After World War II, many Serbs of Montenegro began to identify themselves as Montenegrins. Following the collapse of Communism in Yugoslavia, however, some Montenegrins began to declare as Serbs again, while the largest proportion of citizens of Montenegro still preserved their Montenegrin self-identification. This has deepened further since the movement for full Montenegrin independence from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia began to gain ground in 1991, and ultimately narrowly succeeded in the referendum of May 2006 (having been rejected in 1992).

In the 2011 census, around 280,000 or 44.98% of the population of Montenegro identified themselves as ethnic Montenegrins, while around 180,000 or 28.73% identified themselves as Serbs. The number of "Montenegrins", "Serbs" and "Bosniaks" fluctuates wildly from census to census, not due to real changes in the populace, but due to changes in how people experience their identity. According to the 2002 census, there are around 70,000 ethnic Montenegrins in Serbia, accounting for 0.92% of the Republic's population. In addition, a significant number of Serbs in Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina are of Montenegrin ancestry, but exact numbers are difficult to assess – the inhabitants of Montenegro contributed greatly to the repopulation of a depopulated Serbia after two rebellions against the Ottoman Empire in the early 19th century, with half of the population of Sumadija and its surroundings being populated by people originally from Montenegro, and with several prominent individuals of the Serbian 18th & early 20th century intelligentsia and entrepreneurs being descendants of people originally from Montenegro.

On 19 October 2007 Montenegro adopted a new Constitution which proclaimed Montenegrin (a standardized variety of former Serbo-Croatian) as the official language of Montenegro.

History

Middle Ages

Slavs settled in the Balkans during the 6th and 7th centuries. According to De Administrando Imperio, there existed three Slavic polities on the territory of Montenegro: Duklja, roughly corresponding to the southern half; Travunia, the west; and Serbia (or Rascia), the north. Duklja emerged as an independent state during the 11th century, initially held by the Vojislavljević dynasty, later to be incorporated into the state of the Nemanjić dynasty.

The region previously known as Duklja later became known as "Zeta". Between 1276 and 1309, Serbian queen Helen of Anjou, the widow of the Serbian King Uroš I, ruled Zeta, where she built and restored several monasteries, most notably the Monastery of Saints Sergius and Bacchus (Srđ and Vakh) on the Bojana river below Skadar (Shkodër). The Venetian name Montenegro, meaning "black mountain" occurred for the first time in the charter of St. Nicholas' monastery in Vranjina, dating to 1296, during Jelena's reign. Under King Stefan Milutin (reigned 1282-1321), at the beginning of the 14th century, the Archdiocese in Bar was the biggest feudal domain in Zeta.

In the late 14th century, southern Montenegro (Zeta) came under the rule of the Balšić noble family, then the Crnojević noble family, and by the 15th century, Zeta was more often referred to as Crna Gora (Venetian: monte negro). In 1496, the Ottomans conquered Zeta and subsequently established a sanjak that was subordinated to the Sanjak of Scutari. Ottoman influence remained largely limited to urban areas, while various tribes in the highlands emerged as districts out of reach of the Ottomans. These tribes were at times united against the Ottomans, under the leadership of the Metropolitans of Montenegro, the so-called "prince-bishops".

19th century

The Montenegrins maintained their independence from the Ottoman Empire during the Ottoman's reign over most of the Balkan region (Bosnia, Serbia, Bulgaria, etc.). The Montenegrins were gathered around the Metropolitans of the Cetinje Metropolitanate, which led to further national awakening of the Montenegrins all around. The creation of a theocratic state and its advancement into a secular and independent country was even more evident in the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

The rule of the House of Petrović in the 18th and 19th century unified the Montenegrins and established strong ties with Russia and later with Serbia (under Ottoman occupation), with occasional help from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. That period was marked by numerous battles with Turkish conquerors as well as by a firmer establishment of a self-governed principality.

In 1878, the Congress of Berlin recognised Montenegro as the 26th independent state in the world. Montenegro participated in the Balkan Wars of 1911–1912, as well as in World War I on the side of the Allies.

Yugoslav era

Montenegro unconditionally joined Serbia on November 26, 1918 in a controversial decision of the illegal Podgorica Assembly, and soon afterwards became a part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later renamed as Yugoslavia. A number of Montenegrin chieftains, disappointed by the effective disappearance of Montenegro, which they perceived to have resulted from political manipulation, rose up in arms during January 1919 in an uprising known as the Christmas Rebellion, which was crushed in a severe, comprehensive military campaign in 1922–23. Annexation of the Kingdom of Montenegro on November 13, 1918 gained international recognition only at the Conference of Ambassadors in Paris, held on July 13, 1922.[12] In 1929 the newly renamed Kingdom of Yugoslavia was reorganised into provinces (banovine) one of which, Zeta Banovina, encompassed the old Kingdom of Montenegro and had Cetinje as its administrative centre.

Between the two world wars, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia opposed the Yugoslav monarchy and its unification policy, and supported Montenegrin autonomy, gaining considerable support in Montenegro. During World War II, many Montenegrins joined the Yugoslav partisan forces, although the portion joining the chetniks was also significant. One third of all officers in the partisan army were Montenegrins. They also gave a disproportionate number of highest-ranked party officials and generals. During WWII Italy occupied Montenegro (in 1941) and annexed to the Kingdom of Italy the area of Kotor, where there was a small Roman community (descendants from the populations of the renaissance Albania Veneta). There was an attempt to create an independent Montenegro, but it was stillborn and remained a occupied territory. Montenegro was ravaged by a terrible guerrilla war, mainly after Nazi Germany replaced the defeated Italians in September 1943.

When the second Yugoslavia was formed in 1945, the Communists who led the Partisans during the war formed the new régime. They recognised, sanctioned and fostered a national identity of Montenegrins as a people distinct from the Serbs and other South Slavs. The number of people who were registered as Montenegrins in Montenegro was 90% in 1948; it has been dropping since, to 62% in 1991. With the rise of Serbian nationalism in the late 80's the number of citizens who declared themselves Montenegrin dropped sharply from 61.7%, in the 1991 census, to 43.16% in 2003. For a detailed overview of these trends, see the Demographic history of Montenegro.

Initially, after the fall of Communism in the early 1990s, the idea of a distinct Montenegrin identity has been taken over by independence-minded Montenegrins. The ruling Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS) (reformed communists), led by the prime minister Milo Đukanović and the president Momir Bulatović, was firmly allied with Slobodan Milošević throughout this period and opposed such movements.

During the recent Bosnian War and Croatian War (1991–1995) Montenegro participated with its police and paramilitary forces in the attacks on Dubrovnik and Bosnian towns along with Serbian troops. It conducted persecutions against Bosniak refugees who were arrested by the Montenegrin police and transported to Serb camps in Foča, where they were executed.[13]

Seeking Independence

However, in 1997 a full-blown rift occurred within DPS, and Đukanović's faction won over Bulatović's, who formed a new Socialist People's Party of Montenegro (SNP). The DPS distanced itself from Milošević and gradually took over the independence idea from the Liberal Alliance of Montenegro and the SDP, and has won all elections since.

In the fall of 1999, shortly after the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, the Đukanović-led Montenegrin leadership came out with a platform for the re-definition of relations within the federation that called for more Montenegrin involvement in the areas of defence and foreign policy, though the platform fell short of pushing for independence. After Milošević's overthrow on October 5, 2000, Đukanović for the first time came out in support of full independence and succeeded in his quest by winning a vote on independence on 21 May 2006.

Controversy about Montenegrin ethnic identity

Montenegro was part of medieval Serbia during 12th, 13th and first half of the 14th century. Ottoman conquest of the Balkans resulted in separation from Serbia and the re-emergence of Zeta. In the 19th century national romanticism among the South Slavs fueled the desire for re-unification.

- During Petar I Petrović Njegoš's reign, the basic textbook in state schools was called "The Serb elementary reading book". Another edition was published during Petar II Petrović Njegoš's rule;

- King Nicholas said: "Who isn't loyal to Montenegrinism, he won't be accepted by God and people"

- During the reign of Danilo II Petrovic Njegos, the pupils had classes in Serbian Grammar; Serbian History; and Slavic History.

- The geography syllabus at the College of Theology consisted of "studying the Serb lands independent, subjugated and occupied as well as the main cities, places and villages in the entire Slavhood".

- The geography textbook for the 3rd grade of elementary school, in 1911, said:

- In Montenegro live only true and pure Serbs who speak the Serbian language... Besides Montenegro there are more Serb lands in which our Serb brothers live... Some of them are as free as we are and some are subjugated to foreigners.[14]

- The 1909 census, undertaken by the Principality of Montenegro, recorded that 95% of the population spoke Serbian and followed the Orthodox Christian faith.[15]

Present situation

The political rift in late 1990s caused the Montenegrin/Serb ethnic issue to resurface.

Regarding the issue of independence of Montenegro, voted on a referendum in 2006, the population was roughly divided between ethnic Montenegrins (Orthodox, Muslim, and Catholic), Bosniaks, Croats, and Albanians on one side, and ethnic Serbs on the other.

Various notable people in Montenegro supported Montenegrin independence and acknowledged the right of citizens in Montenegro to declare themselves as ethnic Montenegrins. Noted supporters of independence include current Prime Minister Milo Đukanović and the Speaker of Montenegro's Parliament Ranko Krivokapić. Of the minorities, these include the historical scientist Šerbo Rastoder, a Bosniak from Berane, and don Branko Sbutega (d. 2006), a Croat Roman Catholic priest from Kotor, and the journalist Esad Kočan, of Bosniak descent.

A number of notable individuals declaring as ethnic Montenegrins include famous football players Dejan Savićević, Predrag Mijatović, Stevan Jovetić and Mirko Vučinić; politicians Slavko Perović, Filip Vujanović, and Jusuf Kalamperović (declared as a Montenegrin who professes Islam); comedians Branko Babović, Sekula Drljević, the popular folk singer Sako Polumenta, the former world kick-boxing champion Samir Usenagić, actor Žarko Laušević, fashion model Marija Vujović, members of the rock group Perper, Miraš Dedeić, and former President of Serbia and Montenegro Svetozar Marović.

A number of Montenegrins living outside Montenegro, primarily in Serbia, still maintain Montenegrin folklore, family ties and clan affiliation. They remain Montenegrins by these standards, yet at censa they declare themselves mostly as Serbs. Some have risen to high cultural, economic and political positions. Slobodan Milošević, the Serbian nationalist and President of FR Yugoslavia, was of Montenegrin descent, the first generation of his family to be born in Serbia. His daughter, Marija Milošević declares Montenegrin ethnicity, as did his late brother Borislav, former ambassador to Russia.

Other prominent Serbs having ancestry from what is today Montenegro include the Serbian language reformer Vuk Karadžić, revolutionary leader Karađorđe (paternally), the wartime leader of the Bosnian Serbs Radovan Karadžić,[16] former President of Serbia Boris Tadić,[17] crime boss and warlord Željko Ražnatović-Arkan (paternally),[18] the famous poet and writer Matija Bećković, editor-in-chief of high circulation Večernje novosti daily Manojlo Vukotić, the former basketball star Žarko Paspalj, the BIA chief Rade Bulatović, former Serbian Interior Minister Dragan Jočić,[19] the Serbian constitutional court president Slobodan Vučetić.[19]

Language

Montenegrins speak the Ijekavian variant of the Shtokavian dialect of the Serbo-Croatian language. Neo-shtokavian Eastern-Herzegovinian sub-dialect is spoken in the North-West (largest city Niksic), and old shtokavian Zeta subdialect is spoken in the rest of Montenegro, including capitals Podgorica and Cetinje, and eastern Sanjak.

The Zeta dialect features additional sounds: a voiceless alveolo-palatal fricative (/ɕ/), voiced alveolo-palatal fricative *(/ʑ/, (occurring in other jekavian dialects as well) and a voiced alveolar affricate (dz, shared with other old-štokavian dialects). Both subdialects are charactericized by highly specific accents (shared with other old-štokavian dialects) and several "hyper-ijekavisms" (i.e. nijesam, where the rest of shtokavian area uses nisam) and "hyper-iotations" (đevojka for djevojka, đeca for djeca etc.) (these features, especially the hyper-iotation, are more prominent in Zeta subdialect), that are common in all Montenegrin vernaculars.

On sociolinguistic level, the language has been classified as a dialect of Serbian, being previously a dialect of Serbo-Croatian. The Montenegrin constitution currently defines Montenegrin as the official language. Since the campaign for independence, a movement for recognition of the Montenegrin language as separate from Serbian has emerged, finding the basis for separate language identity mostly in above-mentioned dialectal specifics. The current pro-independence government did not particularly embrace the movement, but did not oppose it either; trying to overcome the situation, the language school classes were renamed from "Serbian language" to "native language", with fierce opposition from pro-Serbian circles. In the 2011 census, 42.88% of Montenegrin citizens stated that they speak the Serbian language, while 36.97% stated that they speak Montenegrin.

Religion

Most declared Montenegrins are Orthodox Christians, predominantly belonging to the Serbian Orthodox Church, the rest belonging to the uncanonical Montenegrin Orthodox Church.

According to the census, people that declared Montenegrin ethnicity declared the following religious identity:

- Eastern Orthodoxy: 246,733

- Sunni Islam: 12,758

- Roman Catholicism: 5,667

- Atheism: 5,867

Culture

The most important dimension of Montenegrin culture is the ethic ideal of Čojstvo i Junaštvo, roughly translated as "Humanity and Bravery". Another result of its centuries long warrior history, is the unwritten code of Chivalry that Marko Miljanov, one of the most famous warriors in his time, tried to describe in his book Primjeri Čojstva i Junaštva (Examples of Humanity and Bravery) at the end of 19th century. Its main principles stipulate that to deserve a true respect of its people, a warrior has to show virtues of integrity, dignity, humility, self-sacrifice for the just cause if necessary, respect for others, and Rectitude along with the bravery. In the old days of battle, it resulted in Montenegrins fighting to the death, since being captured was considered the greatest shame.

It is still very much engraved, to a greater or lesser extent, on every Montenegrin's ethical belief system and it is essential in order to truly understand them. Coming from non-warrior backgrounds, most other South-Slavic nations never fully grasped its meaning, resulting in reactions which ranged from totally ignoring it, in the best case, to mocking it and equating it with backwardness.

Most of extraordinary examples of Montenegrin conduct during its long history can be traced to the code. Its importance is also reflected in the generally very low level of religiousness in the Montenegrin population. It is probably fair to say that the ethical beliefs of Montenegrins more closely match those of Stoicism than those of Christianity.

Montenegrins' long-standing history of fighting for independence is invariably linked with strong traditions of folk epic poetry. A prominent feature of Montenegrin culture is the gusle, a one-stringed instrument played by a story-teller who sings or recites stories of heroes and battles in decasyllabic verse. These traditions are stronger in the northern parts of the country and are also shared with people in eastern Herzegovina, western Serbia, northern Albania and central Dalmatia.

On the substratum of folk epic poetry, poets like Petar II Petrović Njegoš, the Montenegrin icon, have created their own expression. Njegoš's epic book Gorski Vijenac (The Mountain Wreath) presents the central point of Montenegrin culture.

On the other hand, Adriatic cities like Herceg-Novi, Kotor and Budva had strong trade and maritime tradition, and presented an entry-point for Venetian, Ragusan and other Catholic influences. Possession of those cities often changed, but their population was basically a mixture of people with Orthodox and Catholic religions and traditions. These cities were incorporated into Montenegro only after the fall of Austria-Hungary. In those cities, stronger influences of medieval and renaissance architecture, painting, and lyric poetry can be found.

Anthropology

Vlahović (2008) noted many anthropological studies which showed that Montenegrin people have strong Dinaric type (with seaboard, central, Durmitor, mountain and other subtypes) autochthonous on the Dinaric Alps since the Mesolithic period. Dinaric people, including Montenegrins, are the tallest people in the world. The type, particularly in Montenegro, is distinguished by brachiochepal shape, broad forehead, wide relief and strong face, wide jaw and noticeably flat notched head, while arms and legs are proportional to the body height. Hair is commonly of black color, with black or blue eyes.[20]

Anthropologist Božina Ivanović considered that the development of the Montenegrin Dinaric variety was influenced by gracilization and brachycephalization; they have characteristics which were not found in other Slavic and non-Slavic European populations, nor morphological properties from paleo-anthropological series originating from the Slavic necropolis from other South Slavic area. Also, the brachycephalization and width of the face in the last five centuries is growing in Montenegrin, while among other Slavic and European communities decreasing, showing anthropological issues in Montenegro have deeper roots and broader scientific importance.[20] Montenegrin historian Dragoje Živković (1989) noted that modern multidisciplinary research disagrees with older consideration how Sklavinias and Slavic states had ethnical identification, example Serb ethnos, until 12th century.[21] Slavs mixing with native population (in case of Komani culture necropolis in Pukë) made a new cultural-historical drift of Albanian-Illyrian and Slavic built upon extinct and present La Tène, Greek-Illyrian, Illyrian-Roman, and Byzantine.[22] He argued that the Slavs from Duklja promptly blended in social-economical of the natives who historically had more developed and civilized society, as was in their interest to approach the Roman-Illyrian natives.[23]

Genetic studies done in 2010 on 404 male individuals from Montenegro confirmed previous anthropological studies; autochthonous haplogroups I2a (Mesolithic) and E-V13 (Neolithic) make 60% (1:1 ratio), J2 (Neolithic) 9%, R1b 9.5%, while R1a which represents the Slavic superstrata brought during the Middle Ages only 7.5%, with all others less than 5% each.[24]

Notable Montenegrins

See also

| Part of a series on |

| Montenegrins |

|---|

|

| By region or country |

| Recognized populations |

|

Montenegro Serbia Bosnia and Herzegovina Croatia Republic of Macedonia Kosovo Albania |

| Diaspora |

|

Europe · Austria · Denmark France · Germany Italy · Luxembourg Russia · Slovenia Sweden · Switzerland United Kingdom |

|

North America United States · Canada · Mexico |

|

South America Argentina · Chile Bolivia · Brazil · Colombia |

|

Oceania Australia · New Zealand |

| Culture |

|

Literature · Music · Art · Cinema Cuisine · Dress · Sport |

| Religion |

| Language and dialects |

| Montenegrin · Serbian |

| History |

|

History of Montenegro Rulers |

- Montenegrins in Albania

- Montenegrin American

- Montenegrin Argentine

- Montenegrin Australian

- Montenegrins of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Montenegrin Canadian

- Montenegrins of Croatia

- Montenegrins of Kosovo

- Montenegrins of Serbia

- Serbs of Montenegro

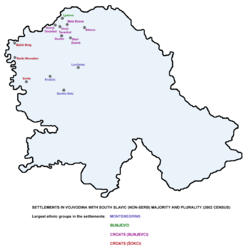

- Lovćenac

- Kruščić

- Savino Selo

- Vrakë

Notes

- a Note: The majority of people originating from within Montenegro's present borders declare ethnic affiliation in censuses as Serb. Thus, it is difficult to establish the exact numbers; up to few million people in Serbia and BiH might have one or more ancestors from Montenegro.

References

- ↑ "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011" (PDF). July 12, 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Radio i Televizija Crne Gore

- ↑ [Official results from the book: Ethnic composition of Bosnia-Herzegovina population, by municipalities and settlements, 1991. census, Zavod za statistiku Bosne i Hercegovine - Bilten no.234, Sarajevo 1991.]

- ↑ http://montenegrina.net/dijaspora/stojovic-u-cileu-zivi-7000-potomaka-crnogoraca/

- ↑ http://www.dzs.hr/Eng/censuses/census2011/results/htm/E01_01_04/e01_01_04_RH.html

- ↑ "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Official Results of Macedonia census 2002, State Staticistal Office of the Republic of Macedonia

- ↑ "Statistini urad RS - Popis 2002". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "20680-Ancestry (full classification list) by Sex - Australia" (Microsoft Excel download). 2006 Census. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2008-06-02. Total responses: 25,451,383 for total count of persons: 19,855,288.

- ↑ "Census 2011 Data: Resident population by ethnic and cultural affiliation". The Institute of Statistics of Republic of Albania. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ↑ "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011" (PDF). Monstat. pp. 14, 15. Retrieved July 12, 2011. For the purpose of the chart, the categories 'Islam' and 'Muslims' were merged; 'Buddhist' (.02) and Other Religions were merged; 'Atheist' (1.24) and 'Agnostic' (.07) were merged; and 'Adventist' (.14), 'Christians' (.24), 'Jehovah Witness' (.02), and 'Protestants' (.02) were merged under 'Other Christian'.

- ↑ http://www.orderofdanilo.org/en/family/index.htm

- ↑ PORODICA NEDŽIBA LOJE O NJEGOVOM HAPŠENJU I DEPORTACIJI 1992. GODINE

- ↑ "Education in Montenegro". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Demographic history of Montenegro

- ↑ BBC: Profile: Radovan Karadzic

- ↑ Kurir, June 30, 2004:Vojislav Koštunica (his grandfather surname was Damjanović, from Katunska nahija) Veselin Konjević: O'kle je Boris

- ↑ IWPR: Milka Tadic: Arkanova Crnogorska Veza

- 1 2

- 1 2 Vlahović, Petar (2008). "Dinarski tip i njegovi varijeteti u Crnoj Gori" [Dinara type and its varieties in Montenegro]. Journal of the Anthropologycal Society of Serbia. Novi Sad. 43: 7–14. ISSN 1820-7936.

- ↑ Živković 1989, p. 97, 103.

- ↑ Živković 1989, p. 94–95.

- ↑ Živković 1989, p. 96, 124.

- ↑ Mirabal 2010, p. 380–390.

Sources

- Mirabal, Sheyla; et al. (July 2010). "Human Y-Chromosome Short Tandem Repeats: A Tale of Acculturation and Migrations as Mechanisms for the Diffusion of Agriculture in the Balkan Peninsula". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 142 (3): 380–390. PMID 20091845. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21235.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Montenegrins. |

- The Montenegrin Association of America

- Špiro Kulišić: O Etnogenezi Crnogoraca (On Ethnogenesis of Montenegrins) (in Montenegrin)

- (in Serbian) Ethnic Origin of Montenegrins by Nikola Vukčević, 1981 (pdf)

- Article about Montenegrin tribes (in montenegrin language)