Monarchy

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Monarchy |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Central concepts |

|

History |

| Politics portal |

A monarchy is a form of government in which a group, generally a family representing a dynasty, embodies the country's national identity and its head, the monarch, exercises the role of sovereignty. The actual power of the monarch may vary from purely symbolic (crowned republic), to partial and restricted (constitutional monarchy), to completely autocratic (absolute monarchy). Traditionally the monarch's post is inherited and lasts until death or abdication. In contrast, elective monarchies require the monarch to be elected.[1] Both types have further variations as there are widely divergent structures and traditions defining monarchy. For example, in some elected monarchies only pedigrees are taken into account for eligibility of the next ruler, whereas many hereditary monarchies impose requirements regarding the religion, age, gender, mental capacity, etc. Occasionally this might create a situation of rival claimants whose legitimacy is subject to effective election. There have been cases where the term of a monarch's reign is either fixed in years or continues until certain goals are achieved: an invasion being repulsed, for instance.

Monarchic rule was the most common form of government until the 19th century. It is now usually a constitutional monarchy, in which the monarch retains a unique legal and ceremonial role, but exercises limited or no official political power: under the written or unwritten constitution, others have governing authority. Currently, 45 sovereign nations in the world have monarchs acting as heads of state, 16 of which are Commonwealth realms that recognise Queen Elizabeth II as their head of state. All European monarchies are constitutional and hereditary but with a strictly symbolic authority, with the exception of the Vatican which is an elective monarchy. The monarchs of Cambodia and Malaysia are also symbolic like their European counterparts and elective like the Vatican. The monarchs of Brunei, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Swaziland have more political influence than any other single source of authority in their nations, either by tradition and/or a constitutional mandate.

Etymology

| Look up monarchy in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

The word "monarch" (Latin: monarcha) comes from the Greek language word μονάρχης, monárkhēs (from μόνος monos, "one, singular", and ἄρχω árkhō, "to rule" (compare ἄρχων arkhon, "leader, ruler, chief")) which referred to a single, at least nominally absolute ruler. In current usage the word monarchy usually refers to a traditional system of hereditary rule, as elective monarchies are rare nowadays.

Depending on the title held by the monarch, a monarchy may be known as a kingdom, principality, duchy, grand duchy, empire, tsardom, emirate, sultanate, khaganate, etc.

History

The form of societal hierarchy known as chiefdom or tribal kingship is prehistoric. The Greek term monarchia is classical, used by Herodotus (3.82). The monarch in classical antiquity is often identified as "king" or "ruler" (translating archon, basileus, rex, tyrannos etc.) or as "queen" (translating basilinna). From earliest historical times, with the Egyptian and Mesopotamian monarchs, as well as in reconstructed Proto-Indo-European religion, the king holds sacral function directly connected to sacrifice, or is considered by their people to have divine ancestry.

The role of the Roman emperor as the protector of Christianity was conflated with the sacral aspects held by the Germanic kings to create the notion of "Divine right of kings" in the Christian Middle Ages. The Chinese, Japanese and Nepalese monarchs continued to be considered living Gods into the modern period.

Since antiquity, monarchy has contrasted with forms of democracy, where executive power is wielded by assemblies of free citizens. In antiquity, monarchies were abolished in favour of such assemblies in Rome (Roman Republic, 509 BC), and Athens (Athenian democracy, 500 BC).

In Germanic antiquity, kingship was primarily a sacral function, and the king was either directly hereditary for some tribes, while for others he was elected from among eligible members of royal families by the thing.

Such ancient "parliamentarism" declined during the European Middle Ages, but it survived in forms of regional assemblies, such as the Icelandic Commonwealth, the Swiss Landsgemeinde and later Tagsatzung, and the High Medieval communal movement linked to the rise of medieval town privileges.

The modern resurgence of parliamentarism and anti-monarchism began with the temporary overthrow of the English monarchy by the Parliament of England in 1649, followed by the American Revolution of 1776 and the French Revolution of 1792. One of many opponents of that trend was Elizabeth Dawbarn, whose anonymous Dialogue between Clara Neville and Louisa Mills, on Loyalty (1794) features "silly Louisa, who admires liberty, Tom Paine and the USA, [who is] lectured by Clara on God's approval of monarchy" and on the influence women can exert on men.[2] Much of 19th century politics was characterised by the division between anti-monarchist Radicalism and monarchist Conservativism.

Many countries abolished the monarchy in the 20th century and became republics, especially in the wake of either World War I or World War II. Advocacy of republics is called republicanism, while advocacy of monarchies is called monarchism. In the modern era, monarchies are more prevalent in small states than in large ones.[3]

Characteristics and role

Monarchies are associated with political or sociocultural hereditary rule, in which monarchs rule for life (although some monarchs do not hold lifetime positions: for example, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong of Malaysia serves a five-year term) and pass the responsibilities and power of the position to their child or another member of their family when they die. Most monarchs, both historically and in the modern day, have been born and brought up within a royal family, the centre of the royal household and court. Growing up in a royal family (called a dynasty when it continues for several generations), future monarchs are often trained for the responsibilities of expected future rule.

Different systems of succession have been used, such as proximity of blood, primogeniture, and agnatic seniority (Salic law). While most monarchs have been male, many female monarchs also have reigned in history; the term queen regnant refers to a ruling monarch, while a queen consort refers to the wife of a reigning king. Rule may be hereditary in practice without being considered a monarchy, such as that of family dictatorships[4] or political families in many democracies.[5]

The principal advantage of hereditary monarchy is the immediate continuity of leadership (as seen in the classic phrase "The King is dead. Long live the King!").

Some monarchies are non-hereditary. In an elective monarchy, monarchs are elected, or appointed by some body (an electoral college) for life or a defined period, but otherwise serve as any other monarch. Three elective monarchies exist today: Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates are 20th-century creations, while one (the papacy) is ancient.

A self-proclaimed monarchy is established when a person claims the monarchy without any historical ties to a previous dynasty. Napoleon I of France declared himself Emperor of the French and ruled the First French Empire after previously calling himself First Consul following his seizure of power in the coup of 18 Brumaire. Jean-Bédel Bokassa of the Central African Republic declared himself "Emperor" of the Central African Empire. Yuan Shikai crowned himself Emperor of the short-lived "Empire of China" a few years after the Republic of China was founded.

Powers of the monarch

- In an absolute monarchy, the monarch rules as an autocrat, with absolute power over the state and government — for example, the right to rule by decree, promulgate laws, and impose punishments. Absolute monarchies are not necessarily authoritarian; the enlightened absolutists of the Age of Enlightenment were monarchs who allowed various freedoms.

- In a constitutional monarchy, the monarch is subject to a constitution. The monarch serves as a ceremonial figurehead symbol of national unity and state continuity. The monarch is nominally sovereign but the electorate, through their legislature, exercise (usually limited) political sovereignty. Constitutional monarchs have limited political power, except in Japan and Sweden, where the constitutions grant no power to their monarchs. Typical monarchical powers include granting pardons, granting honours, and reserve powers, e.g. to dismiss the prime minister, refuse to dissolve parliament, or veto legislation ("withhold Royal Assent"). They often also have privileges of inviolability, sovereign immunity, and an official residence. A monarch's powers and influence may depend on tradition, precedent, popular opinion, and law.

- In other cases the monarch's power is limited, not due to constitutional restraints, but to effective military rule. In the late Roman Empire, the Praetorian Guard several times deposed Roman Emperors and installed new emperors. The Hellenistic kings of Macedon and of Epirus were elected by the army, which was similar in composition to the ecclesia of democracies, the council of all free citizens; military service was often linked with citizenship among the male members of the royal house. Military domination of the monarch has occurred in modern Thailand and in medieval Japan (where a hereditary military chief, the shogun, was the de facto ruler, although the Japanese emperor nominally ruled). In Fascist Italy the Savoy monarchy under King Victor Emmanuel III coexisted with the Fascist single-party rule of Benito Mussolini; Romania under the Iron Guard and Greece during the first months of the Colonels' regime were much the same way. Spain under Francisco Franco was officially a monarchy, although there was no monarch on the throne. Upon his death, Franco was succeeded as head of state by the Bourbon heir, Juan Carlos I, who proceeded to make Spain a democracy with himself as a figurehead constitutional monarch.

Person of monarch

Most states only have a single person acting as monarch at any given time, although two monarchs have ruled simultaneously in some countries, a situation known as diarchy. Historically this was the case in the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta or 17th-century Russia, and there are examples of joint sovereignty of spouses or relatives (such as William III and Mary II in the Kingdoms of England and Scotland). Other examples of joint sovereignty include Tsars Peter I and Ivan V of Russia, and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and Joanna of Castile of the Crown of Castile.

Andorra currently is the world's sole constitutional diarchy or co-principality. Located in the Pyrenees between Spain and France, it has two co-princes: the Bishop of Urgell (a prince-bishop) in Spain and the President of France (inherited ex officio from the French kings, who themselves inherited the title from the counts of Foix). It is the only situation in which an independent country's (co-)monarch is democratically elected by the citizens of another country.

In a personal union, separate independent states share the same person as monarch, but each realm retains its separate laws and government. The sixteen separate Commonwealth realms are sometimes described as being in a personal union with Queen Elizabeth II as monarch, however, they can also be described as being in a shared monarchy.

A regent may rule when the monarch is a minor, absent, or debilitated.

A pretender is a claimant to an abolished throne or to a throne already occupied by somebody else.

Abdication is the act of formally giving up one's monarchical power and status.

Monarchs may mark the ceremonial beginning of their reigns with a coronation or enthronement.

Role of monarch

Monarchy, especially absolute monarchy, sometimes is linked to religious aspects; many monarchs once claimed the right to rule by the will of a deity (Divine Right of Kings, Mandate of Heaven), a special connection to a deity (sacred king) or even purported to be divine kings, or incarnations of deities themselves (imperial cult). Many European monarchs have been styled Fidei defensor (Defender of the Faith); some hold official positions relating to the state religion or established church.

In the Western political tradition, a morally-based, balanced monarchy is stressed as the ideal form of government, and little reverence is paid to modern-day ideals of egalitarian democracy: e.g. Saint Thomas Aquinas unapologetically declares: "Tyranny is wont to occur not less but more frequently on the basis of polyarchy [rule by many, i.e. oligarchy or democracy] than on the basis of monarchy." (On Kingship). However, Thomas Aquinas also stated that the ideal monarchical system would also have at lower levels of government both an aristocracy and elements of democracy in order to create a balance of power. The monarch would also be subject to both natural and divine law, as well, and also be subject to the Church in matters of religion.

In Dante Alighieri's De Monarchia, a spiritualised, imperial Catholic monarchy is strongly promoted according to a Ghibelline world-view in which the "royal religion of Melchizedek" is emphasised against the sacerdotal claims of the rival papal ideology.

In Saudi Arabia, the king is a head of state who is both the absolute monarch of the country and the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques of Islam (خادم الحرمين الشريفين). ––

Titles of monarchs

Monarchs can have various titles. Common European titles of monarchs are emperor or empress (from Latin: imperator or imperatrix), king or queen, grand duke or grand duchess, prince or princess, duke or duchess (in that hierarchical order of nobility).[6] Some early modern European titles (especially in German states) included elector (German: Kurfürst, literally "prince-elector"), margrave (German: Markgraf, equivalent to the French title marquis), and burgrave (German: Burggraf, literally "count of the castle"). Lesser titles include count, princely count, or imam (Use in Oman). Slavic titles include knyaz and tsar (ц︢рь) or tsaritsa (царица), a word derived from the Roman imperial title Caesar.

In the Muslim world, titles of monarchs include caliph (successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of the entire Muslim community), padishah (emperor), sultan or sultana, shâhanshâh (emperor), shah, malik (king) or malikah (queen), emir (commander, prince) or emira (princess), sheikh or sheikha. East Asian titles of monarchs include huángdì (emperor or empress regnant), tiānzǐ (son of heaven), tennō (emperor) or josei tennō (empress regnant), wang (king) or yeowang (queen regnant), hwangje (emperor) or yeohwang (empress regnant). South Asian and South East Asian titles included mahārāja (emperor) or maharani (empress), raja (king) and rana (king) or rani (queen) and ratu (South East Asian queen). Historically, Mongolic or Turkic monarchs have used the title khan and khagan (emperor) or khatun and khanum and Ancient Egypt monarchs have used the title pharaoh for men and women.

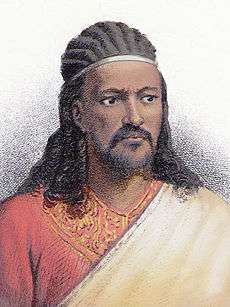

In Ethiopian Empire, monarchs used title nəgusä nägäst (king of kings) or nəgəstä nägäst (queen of kings).

Many monarchs are addressed with particular styles or manners of address, like "Majesty", "Royal Highness", "By the Grace of God", Amīr al-Mu'minīn ("Leader of the Faithful"), Hünkar-i Khanedan-i Âl-i Osman, "Sovereign of the Sublime House of Osman"), Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda ("Majesty"), Jeonha ("Majesty"), Tennō Heika (literally "His Majesty the heavenly sovereign"), Bìxià ("Bottom of the Steps").

Sometimes titles are used to express claims to territories that are not held in fact (for example, English claims to the French throne), or titles not recognised (antipopes). Also, after a monarchy is deposed, often former monarchs and their descendants are given titles (the King of Portugal was given the hereditary title Duke of Braganza).

Dependent monarchies

In some cases monarchs are dependent on other powers (see vassals, suzerainty, puppet state, hegemony). In the British colonial era indirect rule under a paramount power existed, such as the princely states under the British Raj.

In Botswana, South Africa, Ghana and Uganda, the ancient kingdoms and chiefdoms that were met by the colonialists when they first arrived on the continent are now constitutionally protected as regional and/or sectional entities. Furthermore, in Nigeria, though the dozens of sub-regional polities that exist there are not provided for in the current constitution, they are nevertheless legally recognised aspects of the structure of governance that operates in the nation. In addition to these five countries, peculiar monarchies of varied sizes and complexities exist in various other parts of Africa.

Succession

Hereditary monarchies

In a hereditary monarchy, the position of monarch is inherited according to a statutory or customary order of succession, usually within one royal family tracing its origin through a historical dynasty or bloodline. This usually means that the heir to the throne is known well in advance of becoming monarch to ensure a smooth succession.

Primogeniture, in which the eldest child of the monarch is first in line to become monarch, is the most common system in hereditary monarchy. The order of succession is usually affected by rules on gender. Historically "agnatic primogeniture" or "patrilineal primogeniture" was favoured, that is inheritance according to seniority of birth among the sons of a monarch or head of family, with sons and their male issue inheriting before brothers and their issue, and male-line males inheriting before females of the male line.[7] This is the same as semi-Salic primogeniture. Complete exclusion of females from dynastic succession is commonly referred to as application of the Salic law (see Terra salica).

Before primogeniture was enshrined in European law and tradition, kings would often secure the succession by having their successor (usually their eldest son) crowned during their own lifetime, so for a time there would be two kings in coregency – a senior king and a junior king. Examples include Henry the Young King of England and the early Direct Capetians in France.

Sometimes, however, primogeniture can operate through the female line. In some systems a female may rule as monarch only when the male line dating back to a common ancestor is exhausted.

In 1980, Sweden became the first European monarchy to declare equal (full cognatic) primogeniture, meaning that the eldest child of the monarch, whether female or male, ascends to the throne.[8] Other kingdoms (such as the Netherlands in 1983, Norway in 1990, Belgium in 1991, Denmark and Luxembourg[9]) have since followed suit. The United Kingdom adopted absolute (equal) primogeniture on April 25, 2013, following agreement by the prime ministers of the sixteen Commonwealth Realms at the 22nd Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting.

Religion can be a factor in the eligibility of a monarch; for example the British monarch, as head of the Church of England, is required to be in communion with the Church, although all other former rules forbidding marriage to non-Protestants were abolished when equal primogeniture was adopted in 2013.

In the case of the absence of children, the next most senior member of the collateral line (for example, a younger sibling of the previous monarch) becomes monarch. In complex cases, this can mean that there are closer blood relatives to the deceased monarch than the next in line according to primogeniture. This has often led, especially in Europe in the Middle Ages, to conflict between the principle of primogeniture and the principle of proximity of blood.

Other hereditary systems of succession included tanistry, which is semi-elective and gives weight to merit and Agnatic seniority. In some monarchies, such as Saudi Arabia, succession to the throne first passes to the monarch's next eldest brother, and only after that to the monarch's children (agnatic seniority).

Elective monarchies

.jpg)

In an elective monarchy, monarchs are elected, or appointed by some body (an electoral college) for life or a defined period, but otherwise serve as any other monarch. There is no popular vote involved in elective monarchies, as the elective body usually consists of a small number of eligible people. Historical examples of elective monarchy include the Holy Roman Emperors (chosen by prince-electors, but often coming from the same dynasty), and the free election of kings of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. For example, Pepin the Short (father of Charlemagne) was elected King of the Franks by an assembly of Frankish leading men; Stanisław August Poniatowski of Poland was an elected king, as was Frederick I of Denmark. Germanic peoples had elective monarchies.

Five forms of elective monarchies exist today. The pope of the Roman Catholic Church (who rules as Sovereign of the Vatican City State) is elected to a life term by the College of Cardinals. In the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, the Prince and Grand Master is elected for life tenure by the Council Complete of State from within its members. In Malaysia, the federal king, called the Yang di-Pertuan Agong or Paramount Ruler is elected for a five-year term from among and by the hereditary rulers (mostly sultans) of nine of the federation's constitutive states, all on the Malay peninsula. The United Arab Emirates also has a procedure for electing its monarch. Furthermore, Andorra has a unique constitutional arrangement as one of its heads of state is the President of the French Republic in the form of a Co-Prince. This is the only instance in the world where the monarch of a state is elected by the citizens of a different country.

Appointment by the current monarch is another system, used in Jordan. It also was used in Imperial Russia; however, it was changed to semi-Salic soon, because the instability of the appointment system resulted in an age of palace revolutions. In this system, the monarch chooses the successor, who is always his relative.

Current monarchies

Semi-constitutional monarchy Subnational monarchies (traditional)

|

Currently there are 43 nations in the world with a monarch as head of state. They fall roughly into the following categories:

- Commonwealth realms. Queen Elizabeth II is the monarch of sixteen Commonwealth realms (Antigua and Barbuda, the Commonwealth of Australia, the Commonwealth of the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Canada, Grenada, Jamaica, New Zealand, the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, the Federation of Saint Christopher and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland). They have evolved out of the British Empire into fully independent states within the Commonwealth of Nations that retain the Queen as head of state, unlike other Commonwealth countries that are either dependencies, republics or have a different royal house. All sixteen realms are constitutional monarchies and full democracies where the Queen has limited powers or a largely ceremonial role. The Queen is head of the established Church of England in the United Kingdom, while the other 15 realms do not have an established church.

- Other European constitutional monarchies. The Principality of Andorra, the Kingdom of Belgium, the Kingdom of Denmark, Greenland and the Faroe Islands, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Kingdom of Norway, the Kingdom of Spain, and the Kingdom of Sweden are fully democratic states in which the monarch has a limited or largely ceremonial role. There is generally a Christian religion established as the official church in each of these countries. This is the Lutheran form of Protestantism in Norway, Sweden and Denmark, while Belgium and Andorra are Roman Catholic countries. Spain and the Netherlands have no official State religion. Luxembourg, which is very predominantly Roman Catholic, has five so-called officially recognised cults of national importance (Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, Greek Orthodoxy, Judaism and Islam), a status which gives to those religions some privileges like the payment of a state salary to their priests. Andorra is unique among all existing monarchies, as it is, by definition, a diarchy, with the Co-Princeship being shared by the President of France and the Bishop of Urgell. This situation, based on historic precedence, has created a peculiar situation among monarchies, as a) both Co-Princes are not of Andorran descent, b) one is elected by common citizens of a foreign country (France), but not by Andorrans as they cannot vote in the French Presidential Elections, c) the other, the bishop of Urgel, is appointed by a foreign head of state, the Pope.

- European constitutional/absolute monarchies. Liechtenstein and Monaco are constitutional monarchies in which the Prince theoretically retains many powers of an absolute monarch. In reality, he is a figurehead who is expected not to use that power. For example, the 2003 Constitution referendum which gives the Prince of Liechtenstein the power to veto any law that the Landtag (parliament) proposes and the Landtag can veto any law that the Prince tries to pass. The Prince can hire or dismiss any elective member or government employee from his or her post. However, what makes him not an absolute monarch is that the people can call for a referendum to end the monarchy's reign. When Crown Prince Alois threatened to veto a referendum to legalize abortion in 2011 (which didn't actually happen), voters were surprised because the Prince hasn't vetoed any law for over 3 decades. The Prince of Monaco has simpler powers but cannot hire or dismiss any elective member or government employee from his or her post, but he can elect the minister of state, government council and judges. Both Albert II and Hans-Adam II are theoretically very powerful, but in practice even they have very limited power compared to the Islamic monarchs (see below). They also own huge tracts of land and are shareholders in many companies.

- Islamic monarchies. These Islamic monarchs of the Kingdom of Bahrain, the Nation of Brunei, the Abode of Peace, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, the State of Kuwait, Malaysia, the Kingdom of Morocco, the Sultanate of Oman, the State of Qatar, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates generally retain far more powers than their European or Commonwealth counterparts. The Nation of Brunei, the Abode of Peace, the Sultanate of Oman, the State of Qatar, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia remain absolute monarchies; the Kingdom of Bahrain, the State of Kuwait and United Arab Emirates are classified as mixed, meaning there are representative bodies of some kind, but the monarch retains most of his powers. The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, Malaysia and the Kingdom of Morocco are constitutional monarchies, but their monarchs still retain more substantial powers than European equivalents.

- East Asian constitutional monarchies. The Kingdom of Bhutan, the Kingdom of Cambodia, Japan, the Kingdom of Thailand have constitutional monarchies where the monarch has a limited or ceremonial role. The Kingdom of Bhutan, Japan and the Kingdom of Thailand are countries that were never colonised by European powers, but Japan and the Kingdom of Thailand have changed from traditional absolute monarchies into constitutional ones during the twentieth century, while the Kingdom of Bhutan changed in 2008. The Kingdom of Cambodia had its own monarchy after independence from the French Colonial Empire, which was deposed after the Khmer Rouge came into power and the subsequent invasion by the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. The monarchy was subsequently restored in the peace agreement of 1993.

- Other monarchies. Five monarchies do not fit into one of the above groups by virtue of geography or class of monarchy: the Kingdom of Tonga in Polynesia; the Kingdom of Swaziland and the Kingdom of Lesotho in Africa; the Vatican City State; the Sovereign Military Order of Malta in Europe. Of these, the Kingdom of Lesotho and the Kingdom of Tonga are constitutional monarchies, while the Kingdom of Swaziland and the Vatican City State are absolute monarchies. The Kingdom of Swaziland is also unique among these monarchies, often being considered a diarchy. The King, or Ngwenyama, rules alongside his mother, the Ndlovukati, as dual heads of state originally designed to be checks on political power. The Ngwenyama, however, is considered the administrative head of state, while the Ndlovukati is considered the spiritual and national head of state, a position which more or less has become symbolic in recent years.

The Pope is the absolute monarch of the Vatican City State (different entity from the Holy See) by virtue of his position as head of the Roman Catholic Church and Bishop of Rome; he is an elected rather than hereditary ruler and does not have to be a citizen of the territory prior to his election by the cardinals.

The ruling Kim family in North Korea (Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il and Kim Jong-un) has been described as a de facto absolute monarchy[10][11][12] or "hereditary dictatorship".[13] In 2013, Clause 2 of Article 10 of the new edited Ten Fundamental Principles of the Korean Workers' Party states that the party and revolution must be carried "eternally" by the "Baekdu( Kim's) bloodline".[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Stuart Berg Flexure and Lenore Carry Hack, editors, Random House Unabridged Dictionary, 2nd Ed., Random House, New York (1993)

- ↑ The Feminist Companion to Literature in English, ed. Virginia Blain, Patricia Clements and Isobel Grundy, (London: Batsford, 1990), p. 272.

- ↑ Veenendaal, Wouter (2016-01-01). Wolf, Sebastian, ed. State Size Matters. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. pp. 183–198. ISBN 9783658077242. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-07725-9_9.

- ↑ Examples include Oliver Cromwell and Richard Cromwell in the Commonwealth of England, Kim il-Sung and Kim Jong-il in North Korea, the Somoza family in Nicaragua, François Duvalier and Jean-Claude Duvalier in Haiti, and Hafez al-Assad and Bashar al-Assad in Syria.

- ↑ For example, the Kennedy family in the United States and the Nehru-Gandhi family in India. See list of political families.

- ↑ Meyers Taschenlexikon Geschichte 1982 vol.1 p21

- ↑ Murphy, Michael Dean. "A Kinship Glossary: Symbols, Terms, and Concepts". Retrieved October 5, 2006.

- ↑ SOU 1977:5 Kvinnlig tronföljd, p. 16.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-15489544

- ↑ Young W. Kihl, Hong Nack Kim. North Korea: The Politics of Regime Survival. Armonk, New York, USA: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 2006. Pp 56.

- ↑ Robert A. Scalapino, Chong-Sik Lee. The Society. University of California Press, 1972. Pp. 689.

- ↑ Bong Youn Choy. A history of the Korean reunification movement: its issues and prospects. Research Committee on Korean Reunification, Institute of International Studies, Bradley University, 1984. Pp. 117.

- ↑ Sheridan, Michael (16 September 2007). "A tale of two dictatorships: The links between North Korea and Syria". The Times. London. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ↑ The Twisted Logic of the N.Korean Regime, Chosun Ilbo, 2013-08-13, Accessed date: 2017-01-11

External links

| Look up royalty in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Monarchy |

| Look up monarchy in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikivoyage has travel information for Monarchies. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Monarchy. |

- The Constitutional Monarchy Association in the UK

-

"Monarchy". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Monarchy". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

.jpg)