Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy or molecularly targeted therapy is one of the major modalities of medical treatment (pharmacotherapy) for cancer, others being hormonal therapy and cytotoxic chemotherapy. As a form of molecular medicine, targeted therapy blocks the growth of cancer cells by interfering with specific targeted molecules needed for carcinogenesis and tumor growth,[1] rather than by simply interfering with all rapidly dividing cells (e.g. with traditional chemotherapy). Because most agents for targeted therapy are biopharmaceuticals, the term biologic therapy is sometimes synonymous with targeted therapy when used in the context of cancer therapy (and thus distinguished from chemotherapy, that is, cytotoxic therapy). However, the modalities can be combined; antibody-drug conjugates combine biologic and cytotoxic mechanisms into one targeted therapy.

Another form of targeted therapy involves use of nanoengineered enzymes to bind to a tumor cell such that the body's natural cell degradation process can digest the cell, effectively eliminating it from the body. The basic biological mechanism behind such research techniques are under investigation in a limited form with drugs derived from medicinal cannabis (drug) today in the United States. One example includes reduction and elimination of brain tumors with intake of small amounts of oil derived from engineered strains of medicinal cannabis.

Targeted cancer therapies are expected to be more effective than older forms of treatments and less harmful to normal cells. Many targeted therapies are examples of immunotherapy (using immune mechanisms for therapeutic goals) developed by the field of cancer immunology. Thus, as immunomodulators, they are one type of biological response modifiers.

The most successful targeted therapies are chemical entities that target or preferentially target a protein or enzyme that carries a mutation or other genetic alteration that is specific to cancer cells and not found in normal host tissue. One of the most successful molecular targeted therapeutic is Gleevec, which is a kinase inhibitor with exceptional affinity for the oncofusion protein BCR-Abl which is a strong driver of tumorigenesis in Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia. Although employed in other indications, Gleevec is most effective targeting BCR-Abl. Other examples of molecular targeted therapeutics targeting mutated oncogenes, include PLX27892 which targets mutant B-raf in melanoma.

There are targeted therapies for colorectal cancer, head and neck cancer, breast cancer, multiple myeloma, lymphoma, prostate cancer, melanoma and other cancers.[2]

Biomarkers are usually required to aid the selection of patients who will likely respond to a given targeted therapy.[3]

The definitive experiments that showed that targeted therapy would reverse the malignant phenotype of tumor cells involved treating Her2/neu transformed cells with monoclonal antibodies in vitro and in vivo by Mark Greene’s laboratory and reported from 1985.[4]

Some have challenged the use of the term, stating that drugs usually associated with the term are insufficiently selective.[5] The phrase occasionally appears in scare quotes: "targeted therapy".[6] Targeted therapies may also be described as "chemotherapy" or "non-cytotoxic chemotherapy", as "chemotherapy" strictly means only "treatment by chemicals". But in typical medical and general usage "chemotherapy" is now mostly used specifically for "traditional" cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Types

The main categories of targeted therapy are currently small molecules and monoclonal antibodies.

Small molecules

Many are tyrosine-kinase inhibitors.

- Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec, also known as STI–571) is approved for chronic myelogenous leukemia, gastrointestinal stromal tumor and some other types of cancer. Early clinical trials indicate that imatinib may be effective in treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.

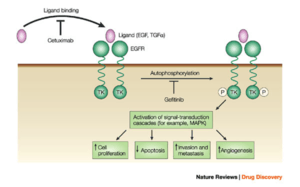

- Gefitinib (Iressa, also known as ZD1839), targets the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase and is approved in the U.S. for non small cell lung cancer.

- Erlotinib (marketed as Tarceva). Erlotinib inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor,[7] and works through a similar mechanism as gefitinib. Erlotinib has been shown to increase survival in metastatic non small cell lung cancer when used as second line therapy. Because of this finding, erlotinib has replaced gefitinib in this setting.

- Sorafenib (Nexavar)[8]

- Sunitinib (Sutent)

- Dasatinib (Sprycel)

- Lapatinib (Tykerb)

- Nilotinib (Tasigna)

- Bortezomib (Velcade) is an apoptosis-inducing proteasome inhibitor drug that causes cancer cells to undergo cell death by interfering with proteins. It is approved in the U.S. to treat multiple myeloma that has not responded to other treatments.

- The selective estrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen has been described as the foundation of targeted therapy.[9]

- Janus kinase inhibitors, e.g. FDA approved tofacitinib

- ALK inhibitors, e.g. crizotinib

- Bcl-2 inhibitors (e.g. obatoclax in clinical trials, navitoclax, and gossypol.[10]

- PARP inhibitors (e.g. Iniparib, Olaparib in clinical trials)

- PI3K inhibitors (e.g. perifosine in a phase III trial)

- Apatinib is a selective VEGF Receptor 2 inhibitor which has shown encouraging anti-tumor activity in a broad range of malignancies in clinical trials.[11] Apatinib is currently in clinical development for metastatic gastric carcinoma, metastatic breast cancer and advanced hepatocellular carcinoma.[12]

- AN-152, (AEZS-108) doxorubicin linked to [D-Lys(6)]- LHRH, Phase II results for ovarian cancer.[13]

- Braf inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib, LGX818) used to treat metastatic melanoma that harbors BRAF V600E mutation

- MEK inhibitors (trametinib, MEK162) are used in experiments, often in combination with BRAF inhibitors to treat melanoma

- CDK inhibitors, e.g. PD-0332991, LEE011 in clinical trials

- Hsp90 inhibitors, some in clinical trials

- salinomycin has demonstrated potency in killing cancer stem cells in both laboratory-created and naturally occurring breast tumors in mice.

- VAL-083 (dianhydrogalactitol), a “first-in-class” DNA-targeting agent with a unique bi-functional DNA cross-linking mechanism[14][15]. NCI-sponsored clinical trials have demonstrated clinical activity against a number of different cancers including glioblastoma, ovarian cancer, and lung cancer. VAL-083 is currently undergoing Phase 2 and Phase 3 clinical trials as a potential treatment for glioblastoma (GBM). As of July 2017, four different trials of VAL-083 are registered[16].

Small molecule drug conjugates

- Vintafolide is a small molecule drug conjugate consisting of a small molecule targeting the folate receptor. It is currently in clinical trials for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (PROCEED trial) and a Phase 2b study(TARGET trial) in non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC).[17]

Serine/threonine kinase inhibitors (small molecules)

- Temsirolimus (Torisel)

- Everolimus (Afinitor)

- Vemurafenib (Zelboraf)

- Trametinib (Mekinist)

- Dabrafenib (Tafinlar)

Monoclonal antibodies

Several are in development and a few have been licensed by the FDA and the European Commission. Examples of licensed monoclonal antibodies include:

- Rituximab targets CD20 found on B cells. It is used in non Hodgkin lymphoma

- Trastuzumab targets the Her2/neu (also known as ErbB2) receptor expressed in some types of breast cancer

- Alemtuzumab

- Cetuximab target the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). It is approved for use in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer,[18][19] and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck.,[20][21]

- Panitumumab also targets the EGFR. It is approved for the use in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer.

- Bevacizumab targets circulating VEGF ligand. It is approved for use in the treatment of colon cancer, breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and is investigational in the treatment of sarcoma. Its use for the treatment of brain tumors has been recommended.[22]

- Ipilimumab (Yervoy)

Many antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) are being developed. See also ADEPT (antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy).

Progress and future

In the U.S., the National Cancer Institute's Molecular Targets Development Program (MTDP) aims to identify and evaluate molecular targets that may be candidates for drug development.

See also

References

- ↑ "Definition of targeted therapy - NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms".

- ↑ NCI: Targeted Therapy tutorials

- ↑ Syn, Nicholas Li-Xun; Yong, Wei-Peng; Goh, Boon-Cher; Lee, Soo-Chin (2016-08-01). "Evolving landscape of tumor molecular profiling for personalized cancer therapy: a comprehensive review". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 12 (8): 911–922. ISSN 1744-7607. PMID 27249175. doi:10.1080/17425255.2016.1196187.

- ↑ Perantoni AO, Rice JM, Reed CD, Watatani M, Wenk ML (September 1987). "Activated neu oncogene sequences in primary tumors of the peripheral nervous system induced in rats by transplacental exposure to ethylnitrosourea". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84 (17): 6317–6321. PMC 299062

. PMID 3476947. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.17.6317.

. PMID 3476947. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.17.6317.

Drebin JA, Link VC, Weinberg RA, Greene MI (December 1986). "Inhibition of tumor growth by a monoclonal antibody reactive with an oncogene-encoded tumor antigen". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83 (23): 9129–9133. PMC 387088 . PMID 3466178. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.23.9129.

. PMID 3466178. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.23.9129.

Drebin JA, Link VC, Stern DF, Weinberg RA, Greene MI (July 1985). "Down-modulation of an oncogene protein product and reversion of the transformed phenotype by monoclonal antibodies". Cell. 41 (3): 697–706. PMID 2860972. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(85)80050-7. - ↑ Zhukov NV, Tjulandin SA (May 2008). "Targeted therapy in the treatment of solid tumors: practice contradicts theory". Biochemistry Mosc. 73 (5): 605–618. PMID 18605984. doi:10.1134/S000629790805012X.

- ↑ Markman M (2008). "The promise and perils of 'targeted therapy' of advanced ovarian cancer". Oncology. 74 (1–2): 1–6. PMID 18536523. doi:10.1159/000138349.

- ↑ Katzel JA, Fanucchi MP, Li Z (January 2009). "Recent advances of novel targeted therapy in non-small cell lung cancer". J Hematol Oncol. 2 (1): 2. PMC 2637898

. PMID 19159467. doi:10.1186/1756-8722-2-2.

. PMID 19159467. doi:10.1186/1756-8722-2-2. - ↑ Lacroix, Marc (2014). Targeted Therapies in Cancer. Hauppauge , NY: Nova Sciences Publishers. ISBN 978-1-63321-687-7.

- ↑ Jordan VC (January 2008). "Tamoxifen: catalyst for the change to targeted therapy". Eur. J. Cancer. 44 (1): 30–38. PMC 2566958

. PMID 18068350. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2007.11.002.

. PMID 18068350. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2007.11.002. - ↑ Warr MR, Shore GC (December 2008). "Small-molecule Bcl-2 antagonists as targeted therapy in oncology". Curr Oncol. 15 (6): 256–61. PMC 2601021

. PMID 19079626.

. PMID 19079626. - ↑ Li J, Zhao X, Chen L, et al. (2010). "Safety and pharmacokinetics of novel selective vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 inhibitor YN968D1 in patients with advanced malignancies". BMC Cancer. 10: 529. PMC 2984425

. PMID 20923544. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-10-529.

. PMID 20923544. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-10-529. - ↑ http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=apatinib

- ↑ "Phase II study of AEZS-108 (AN-152), a targeted cytotoxic LHRH analog, in patients with LHRH receptor-positive platinum resistant ovarian cancer.". 2010.

- ↑ [American Association for Cancer Research "Molecular mechanisms of dianhydrogalactitol (VAL-083) in overcoming chemoresistance in glioblastoma"] Check

|url=value (help). American Association for Cancer Research. Beibei Zhai, Anna Gobielewska, Anne Steino, Jeffrey A. Bacha, Dennis M. Brown, Simone Niclou and Mads Daugaard. - ↑ "DNA damage response to dianhydrogalactitol (VAL-083) in p53-deficient non-small cell lung cancer cells". American Association for Cancer Research. Anne Steino, Guangan He, Jeffrey A. Bacha, Dennis M. Brown and Zahid Siddik.

- ↑ "VAL-083 Clinical Trials". Clinical Trials . GOV. U.S. National Institutes of Health.

- ↑

- ↑ “Therascreen KRAS RGQ PCR Kit – P110030“. Device Approvals and Clearances. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2012-07-06.

- ↑ European medicines Agency (June 2014). “Erbitux® Summary of Product Characteristics (PDF).“ 2015-11-19.

- ↑ “Cetuximab (Erbitux). About the Center of Drug Evaluation and Research." U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2015-11-16.

- ↑ "Merck KGaA: European Commission Approves Erbitux for First-Line Use in Head and Neck Cancer" 2015-11-16

- ↑ Pollack, Andrew (2009-03-31). "F.D.A. Panel Supports Avastin to Treat Brain Tumor". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

External links

- CancerDriver : a free and open database to find targeted therapies according to the patient's features.

- Targeted Therapy Database (TTD) from the Melanoma Molecular Map Project

- Targeted therapy Fact sheet from the U.S. National Cancer Institute

- Molecular Oncology: Receptor-Based Therapy Special issue of Journal of Clinical Oncology (April 10, 2005) dedicated to targeted therapies in cancer treatment

- Targeting Targeted Therapy New England Journal of Medicine (2004)

- Targeting tumors with medicinal cannabis oil - publication list from Spain