Mokele-mbembe

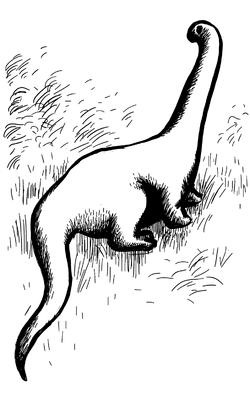

A sketch of Mokele-mbembe. | |

| Grouping | Cryptid |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Lake monster |

| Region | Congo River basin |

| Habitat | Water |

Mokèlé-mbèmbé (meaning "one who stops the flow of rivers"[1] in the Lingala language) is a legendary water-dwelling creature of Congo River basin folklore, sometimes described as a living creature, sometimes as a spirit, and loosely analogous to the Loch Ness Monster in Western culture. It is claimed to be a sauropod by some cryptozoologists.[2]

Expeditions mounted in the hope of finding evidence of the Mokèlé-mbèmbé have failed, and the subject has been covered in a number of books and by a number of television documentaries. According to skeptic Robert T. Carroll, "Reports of the Mokèlé-mbèmbé have been circulating for the past two hundred years, yet no one has photographed the creature or produced any physical evidence of its existence."[3] The Mokèlé-mbèmbé and its associated folklore also appear in several works of fiction and popular culture.[2]

Overview

According to the traditions of the Congo River basin the Mokèlé-mbèmbé is a large territorial herbivore. It is said to dwell in Lake Tele and the surrounding area,[2] with a preference for deep water, and with local folklore holding that its haunts of choice are river bends.[2]

Descriptions of the Mokèlé-mbèmbé vary. Some legends describe it as having an elephant-like body with a long neck and tail and a small head, a description which has been suggested to be similar in appearance to that of the extinct Sauropoda,[2] while others describe it as more closely resembling elephants, rhinoceros, and other known animals. It is usually described as being gray-brown in color. Some traditions, such as those of Boha Village, describe it as a spirit rather than a flesh and blood creature.

The BBC/Discovery Channel documentary Congo (2001) interviewed a number of tribe members who identified a photograph of a rhinoceros as being a Mokèlé-mbèmbé.[4] Neither species of African rhinoceros is common in the Congo Basin, and the Mokèlé-mbèmbé may be a mixture of mythology and folk memory from a time when rhinoceros were found in the area.

History

Numerous expeditions have been undertaken to Africa in search of Mokèlé-mbèmbé. During these, there were some sightings that have been argued by cryptozoologists to involve some unidentified dinosaur-like creature. Additionally, there have been several specific Mokèlé-mbèmbé-hunting expeditions.[2] Although several of the expeditions have reported close encounters, none have been able to provide incontrovertible proof that the creature exists.[2] The sole evidence that has been found is the presence of widespread folklore and anecdotal accounts covering a considerable period of time.[2]

1776: Bonaventure

The earliest reference that might be relevant to Mokèlé-mbèmbé stories (though the term is not used in the source) comes from the 1776 book History of Loango, Kakonga, and Other Kingdoms in Africa by Liévin-Bonaventure Proyart, a French missionary to the Congo River region. Among many other observations about flora, fauna, and native inhabitants related in his book, Bonaventure claimed to have seen enormous footprints in the region. The creature that left the prints was not witnessed, but Bonaventure wrote that it "must have been monstrous: the marks of the claws were noted on the ground, and these formed a print about three feet in circumference."[2]

1909: Gratz

According to Lt. Paul Gratz's account from 1909, indigenous legends of the Congo River Basin in modern day Zambia spoke of a creature known by native people as the "Nsanga", which was said to inhabit the Lake Bangweulu region. Gratz described the creature as resembling a sauropod.[2] This is one of the earliest references linking an area legend with dinosaurs, and has been argued to describe a Mokèlé-mbèmbé-like creature. In addition to hearing stories of the "Nsanga" Gratz was shown a hide which he was told belonged to the creature, while visiting Mbawala Island.

1909: Hagenbeck

1909 saw another mention of a Mokèlé-mbèmbé-like creature, in Beasts and Men, the autobiography of famed big-game hunter Carl Hagenbeck. He claimed to have heard from multiple independent sources about a creature living in the Congo region which was described as "half elephant, half dragon."[2] Naturalist Joseph Menges had also told Hagenbeck about an animal alleged to live in Africa, described as "some kind of dinosaur, seemingly akin to the brontosaurs."[2] Another of Hagenbeck's sources, Hans Schomburgk, asserted that while at Lake Bangweulu, he noted a lack of hippopotami; his native guides informed him of a large hippo-killing creature that lived in Lake Bangweulu; however, as noted below, Schomburgk thought that native testimony was sometimes unreliable.

Reports of dinosaur-like creatures in Africa caused a minor sensation in the mass media, and newspapers in Europe and North America carried many articles on the subject in 1910–1911; some took the reports at face value, others were more skeptical.

1913: von Stein

Another report comes from the writings of German Captain Ludwig Freiherr von Stein zu Lausnitz, who was ordered to conduct a survey of German colonies in what is now Cameroon in 1913. He heard stories of an enormous reptile alleged to live in the jungles, and included a description of the beast in his official report. According to Willy Ley, "von Stein worded his report with utmost caution," knowing it might be seen as unbelievable.[5] Nonetheless, von Stein thought the tales were credible: trusted native guides had related the tales to him, and the stories were related to him by independent sources, yet featured many of the same details. Though von Stein's report was never formally published, portions were included in later works, including a 1959 book by Ley. Von Stein wrote:

The animal is said to be of a brownish-gray color with a smooth skin, its size is approximately that of an elephant; at least that of a hippopotamus. It is said to have a long and very flexible neck and only one tooth but a very long one; some say it is a horn. A few spoke about a long, muscular tail like that of an alligator. Canoes coming near it are said to be doomed; the animal is said to attack the vessels at once and to kill the crews but without eating the bodies. The creature is said to live in the caves that have been washed out by the river in the clay of its shores at sharp bends. It is said to climb the shores even at daytime in search of food; its diet is said to be entirely vegetable. This feature disagrees with a possible explanation as a myth. The preferred plant was shown to me, it is a kind of liana with large white blossoms, with a milky sap and applelike fruits. At the Ssombo River I was shown a path said to have been made by this animal in order to get at its food. The path was fresh and there were plants of the described type nearby. But since there were too many tracks of elephants, hippos, and other large mammals it was impossible to make out a particular spoor with any amount of certainty.[6]

1919-1920: Smithsonian Institution

A 32-man expedition was sent to Africa from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. between 1919 and 1920. The objective of this expedition was to secure additional specimens of plants and animals. Moving picture photographers from the Universal Film Manufacturing Company accompanied the expedition, in order to document the life of interior Africa. According to cryptozoologists Loren Coleman and Patrick Huyghe, authors of the Field Guide to Lake Monsters, "African guides found large, unexplained tracks along the bank of a river and later in a swamp the team heard mysterious roars, which had no resemblance with any known animal".[7] However, the expedition was to end in tragedy. During a train-ride through a flooded area where an entire tribe was said to have seen the dinosaur, the locomotive suddenly derailed and turned over. Four team members were crushed to death under the cars and another half dozen seriously injured. The expedition was documented in the Homer L. Shantz papers.[8]

1927: Smith

1927 saw the publication of Trader Horn, the memoir of Alfred Aloysius Smith, who had worked for a British trading company in what is now Gabon in the late 1800s. In the book, Smith related tales told him by natives and explorers about a creature given two different names: "jago-nini" and "amali". The creature was said to be very large, according to Smith, and to leave large, round, three-clawed footprints.[2]

1932: Sanderson

Cryptozoologist Ivan T. Sanderson claimed that, while in Cameroon in 1932, he witnessed an enormous creature in the Mainyu River. The creature, seemingly badly wounded, was only briefly visible as it lurched into the water. Darkly colored, the animal's head alone was nearly the size of a hippo, according to Sanderson. His native guides termed the creature "m'koo m'bemboo", in Sanderson's phonetic spelling.[2]

1938: von Boxberger

In 1938, explorer Leo von Boxberger mounted an expedition in part to investigate Mokèlé-mbèmbé reports. He collected much information from natives, but his notes and sketches had to be abandoned during a conflagration with local tribesmen.[2]

1939: von Nolde

In 1939, the German Colonial Gazette (of Angola) published a letter by Frau Ilse von Nolde, who asserted that she had heard of the animal called "coye ya menia" ("water lion") from many claimed eyewitnesses, both natives and settlers. She described the long necked creature as living in the rivers, and being about the size of a hippo, if not somewhat larger. It was known especially for attacking hippos - even coming on to land to do so - though it never ate them.[9]

1966: Ridel

In August or September 1966, Yvan Ridel took a picture of a large footprint with three toes, north-east of Loubomo, notable as hippopotamuses have four toes.[10][11]

1976: Powell

In 1960, an expedition to Zaire was planned by herpetologist James H. Powell, Jr., scheduled for 1972, but was canceled by legal complications. By 1976, however, he had sorted out the international travel problems, and went to Gabon instead, inspired by the book Trader Horn. He secured finances from the Explorer's Club. Although Powell’s ostensible research aim was to study crocodiles, he also planned to study Mokèlé-mbèmbé.

On this journey, Powell located a claimed eyewitness to an animal called "n'yamala", or "jago-nini", which Powell thought was the same as the "amali" of Smith's 1920's books. Natives also stated – without Powell's asking - that "n'yamala" ate the flowering liana, just as von Stein had been told half a century earlier.[2] When Powell showed illustrations of various animals, both alive and extinct, to natives, they generally suggested that the Diplodocus was the closest match to "n'yamala".[2]

1979: Powell

Powell returned to the same region in 1979, and claimed to receive further stories about "n'yamala" from additional natives. He also made an especially valuable contact in American missionary Eugene Thomas, who was able to introduce Powell to several claimed eyewitnesses.[2] He decided that the n'yamala was probably identical to the Mokèlé-mbèmbé. Though seemingly herbivores, witnesses reported that the creatures were fearsome, and were known to attack canoes that were steered too close.

1979: Thomas

Reverend Eugene Thomas from Ohio, USA, told James Powell and Roy P. Mackal in 1979 a story that involved the purported killing of a Mokèlé-mbèmbé near Lake Tele in 1959.[12] Thomas was a missionary who had served in the Congo since 1955, gathering much of the earliest evidence and reports, and claiming to have had two close-encounters himself.[13] Natives of the Bangombe tribe who lived near Lake Tele were said to have constructed a large spiked fence in a tributary of Tele to keep Mokèlé-mbèmbé from interfering with their fishing. A Mokele-mbembe managed to break through, though it was wounded on the spikes, and the natives then killed the creature. As William Gibbons writes, "Pastor Thomas also mentioned that the two pygmies mimicked the cry of the animal as it was being attacked and speared... Later, a victory feast was held, during which parts of the animal were cooked and eaten. However, those who participated in the feast eventually died, either from food poisoning or from natural causes. I also believe that the mythification (magical powers, etc) surrounding Mokèlé-mbèmbés [sic] began with this incident." Furthermore, Mackal heard from witnesses that the stakes were in the same location in the tributary as of the early 1980s.[10]

1980: Mackal-Powell

For his third expedition in February 1980, Powell was joined by Roy P. Mackal. Based on the testimony of claimed eyewitnesses, Powell and Mackal decided to focus their efforts on visiting the northern Congo regions, near the Likouala aux Herbes River and isolated Lake Tele. As of 1980, this region was little explored and largely unmapped, and the expedition was unable to reach Lake Tele. Powell and Mackal interviewed several people who claimed to have seen Mokèlé-mbèmbé, and Clark writes that the descriptions of the creature were "strikingly similar ... animals 15 to 30 feet (5 to 9 m) long (most of that a snakelike head and neck, plus long thin tail). The body was reminiscent of a hippo's, only more bulbous ... again, informants invariably pointed to a picture of a sauropod when shown pictures of various animals to which mokele-mbembe might be compared."[2][10] Mackal and Powell were interviewed before and after this expedition for the TV program Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World.

1981: Mackal-Bryan

Mackal and Jack Bryan mounted an expedition to the same area in late 1981. He was supposed to be joined by Herman Regusters, but they came in conflict in terms of finance, equipment and leadership and decided to split and make separate expeditions. Although, once again, Mackal was unable to reach Lake Tele, he gathered details on other cryptids and possible living dinosaurs, like the Emela-ntouka, Mbielu-Mbielu-Mbielu, Nguma-monene, Ndendeki (giant turtle), Mahamba (a giant crocodile of 15 meters), and Ngoima (a giant monkey-eating Eagle). Among his company were J. Richard Greenwell, M. Justin Wilkinson, and Congolese zoologist Marcellin Agnagna.[2][10]

The 1981 expedition would feature the only "close encounters" of the Mackal expeditions. It occurred when, while on a river, they heard a loud splash and saw what Greenwell described as "[a] large wake (about 5") ... originating from the east bank".[2][10] Greenwell asserted that the wake must have been caused by an "animate object" that was unlike a crocodile or hippo. Additionally, Greenwell noted that the encounter occurred at a sharp river bend where, according to natives, Mokèlé-mbèmbé frequently lived due to deep waters at those points.[2][10]

1987 saw the publication of Mackal's book, A Living Dinosaur?, in which Mackal detailed his expedition and his conclusions about the Mokèlé-mbèmbé.[2][10] Mackal tried, unsuccessfully, to raise funds for additional trips to Africa.[10]

1981: Regusters

In 1981, American engineer Herman Regusters led his own Mokèlé-mbèmbé expedition, after having a conflict with the Mackal-Bryan expedition that he intended to join. Regusters and his wife Kai reached Lake Tele, staying there for about two weeks. Of the 30 expedition members (28 were men from the Boha village), only Herman Regusters and his wife claim to have observed a "long-necked member" traveling across Lake Tele. They also claim to have tried filming the being, but said their motion picture film was ruined by the heat and humidity. Only one picture was released showing a large, but unidentifiable, object in the lake.[14] The Regusters expedition returned with droppings and footprint casts, which Regusters believed were from the mokele-mbembe.[15]

It also returned with sound recordings of "low windy roar [that] increased to a deep throated trumpeting growl", which Regusters believed to be the Mokèlé-mbèmbé's call.[2] This recording was submitted for technical evaluation with a noted physicist, Kenith W. Templin, whose specialty was sound waves and vibration analysis, but it was inconclusive, except to note that the sounds were not attributable to any known wildlife. Despite this result, Regusters' conclusions about this tape were later challenged by Mackal, who asserted that the Mokèlé-mbèmbé did not have a vocal call. Mackal asserts that vocalizations are more correctly associated with the Emela-ntouka, a similarly described creature found in the Central African legends.

Herman Alphanso Regusters died on 19 December 2005, aged 72.

1983: Agnagna

Congolese biologist Marcellin Agnagna led the 1983 expedition of Congolese to Lake Tele. According to his own account, Agnagna claimed to have seen a Mokèlé-mbèmbé at close distance for about 20 minutes. He tried to film it, but said that in his excitement, he forgot to remove the motion picture camera's lens cap. In a 1984 interview, Agnagna claimed, contradictorily, that the film was ruined not because of the lens cap, but because he had the Super 8 camera on the wrong setting: macro instead of telephoto.[2][16]

1985: Nugent

In December 1985 Rory Nugent spotted an anomaly moving through the middle of Lake Tele, approximately 1 kilometer from his position on the shore. In his account published as a book, Nugent claimed that it was shaped like a "slender french curve" and moving through the water with little wake. When he went to launch a boat to investigate he was ordered at gunpoint by the natives not to approach it.[17] Nugent wrote that they view the creature as a god "that you can not approach, but if he chooses, this god can approach you." [17] He also provided some pictures, which are too blurry to be identifiable.

1985-1986: Operation Congo

Operation Congo took place between December 1985 and early 1986 by "four enthusiastic but naïve young Englishmen," led by Young Earth Creationist[16] William Gibbons,[2] They hired Agnagna to take them to Lake Tele, but did not report any Mokèlé-mbèmbé sightings. The British men did, however, assert that Agnagna did "little more than lie, cheat and steal (our film and supplies) and turn the porters against us."[2] After criminal charges were filed against him, a Congolese court ordered Agnagna to return the items he had taken from the expedition.

Although the party found no evidence of the Mokèlé-mbèmbé, they discovered a new subspecies of monkey, which was later classified as the Crested mangabey monkey (Cerocebus galeritus), as well as fish and insect specimens.[16]

1986: Botterweg

In 1986 another expedition was mounted, consisting of four Dutchmen, organized and led by Dutch biologist Ronald Botterweg, who already had experience with tropical rainforest research in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and who later visited, lived, and worked in several African countries. This expedition entered the Congo down the Ubangi River from Bangui in the Central African Republic, and managed, with considerable organizational challenges, to reach Lake Tele, with a group of guides from the village of Boha, some of which had also accompanied Regusters. Since they had only managed to obtain permission from the local authorities (not having passed by Brazzaville) for a very limited period in the area, they only spent about three days at the lake before returning to Boha. During their stay at the lake they spent as much time as possible observing the lake and its surroundings through from their provisional camp on the north-eastern shore, and navigating part of it by dug-out canoe. No signs of any large unknown animal were found.

On the way back, arriving at the town of Impfondo, they were detained by Congolese biologist Agnagna and his team, who had just arrived there for an expedition with the British team of Operation Congo, allegedly for not possessing the proper documents. They were detained for a short while, and the largest part of their film and color slides were confiscated, before being released and leaving the country (again by the Ubangui river and Bangui).

No signs, tracks or anything tangible or visible of the alleged animals was seen or shown whatsoever. Tracks, droppings, and other signs of forest elephants and gorillas were commonly seen, as well as crocodiles in the lake. Despite the fact that the African guides were extremely capable and experienced hunters, guides and experts of the African rainforest, they were not able to show any track or sign of the Mokèlé-mbèmbé and none of the several interviewed guides even claimed ever to have seen one personally, nor its tracks. Remarkable is the fact that the guides that were interviewed by the Dutch expedition and that also accompanied Regusters, stated that they never saw a Mokèlé-mbèmbé during that expedition, although Regusters himself claims to have seen one.

This expedition received some attention in the Dutch media (radio, TV, and newspapers) from 1985 to 1987, and again in a nostalgic radio show by Dutch radio station KRO on channel Radio 2, on 7 March 2011. Furthermore, this expedition features in a slightly romanticized form as a short story by Dutch novelist author Margriet de Moor ('Hij Bestaat', meaning It exists, in the novel 'Op de Rug Gezien', meaning Seen from behind).

1988 Japanese expedition

In 1988 a Japanese expedition went to the area,[18] led by the Congolese wildlife official Jose Bourges. In 1992, members of a Japanese film crew allegedly filmed video Mokele-mbembe.[19] As they were filming aerial footage from a small plane over the area of Lake Tele, intending to obtain some shots for a documentary, the cameraman noticed a disturbance in the water. He struggled to maintain focus on the object, which was creating a noticeable wake. About 15 seconds of footage was captured, which skeptics have identified as either two men in a canoe or swimming elephants.

1989 O'Hanlon

British writer Redmond O'Hanlon traveled to the region in 1989 and not only failed to discover any evidence of Mokèlé-mbèmbé but found out that many local people believe the creature to be a spirit rather than a physical being, and that claims for its authentic existence have been fabricated. His experience is chronicled in Granta no. 39 (1992) and in his book Congo Journey (UK, 1996), published as No Mercy in the USA (1997).

1992 Operation Congo 2

William Gibbons launched a second expedition in 1992 which he dubbed "Operation Congo 2". Along with Rory Nugent, Gibbons searched almost two thirds of the Bai River along with two poorly charted lakes: Lake Fouloukuo and Lake Tibeke, both of which local folklore held to be sites of Mokèlé-mbèmbé activity. The expedition failed to provide any conclusive evidence of the Mokèlé-mbèmbé, though they did further document local legends and Nugent took two photographs of unidentified objects in the water, one of which he claimed was the creature's head.

2000: Extreme Expeditions

In January 2000, the Congo Millennium Expedition (aka. DINO2000) took place, the second one by Extreme Expeditions, consisting of Andrew Sanderson, Adam Davies, Keith Townley, Swedish explorer Jan-Ove Sundberg, and five others.[20] (Adam Davies has spoken of the Mokèlé-mbèmbé on a 2011 BBC video.[21])

2000: Gibbons

In November 2000, William Gibbons did some preliminary research in Cameroon for a future expedition. He was accompanied by David Wetzel, and videographer Elena Dugan. While visiting with a group of pygmies, they were informed about an animal called Ngoubou, a horned creature. The pygmies asserted it was not a regular rhinoceros, as it had more than one horn (six horns on the frill in one eyewitness account), and that the father of one of the senior members of the community had killed one with a spear a number of years ago. The locals have noted a firm dwindle in the population of these animals lately, and that they are hard to find. Gibbons identified the animal with a Styracosaurus, but, in addition to being extinct, these are only known to have inhabited North America.[22]

2001: CryptoSafari/BCSCC

In February 2001, in a joint venture between CryptoSafari and the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club (BCSCC), a research team traveled to Cameroon consisting of William Gibbons, Scott T. Norman, John Kirk and writer Robert A. Mullin. Their local guide was Pierre Sima Noutchegeni. They were also accompanied by a BBC film crew. No evidence of Mokèlé-mbèmbé was found.[23]

2001: BBC Congo

In 2001, BBC broadcast in the TV series Congo a collective interview with a group of BiAka pygmies, who identified the mokele mbembe as the rhinoceros while looking at an illustrated manual of local wildlife.[24] Neither species of African rhinoceros is common in the Congo Basin, and the Mokèlé-mbèmbé may be a mixture of mythology and folk memory from a time when rhinoceros were found in the area.

2006: Marcy

In January 2006, the Milt Marcy Expedition traveled to the Dja river in Cameroon, near the Congolese border. It consisted of Milt Marcy, Peter Beach, Rob Mullin and Pierre Sima. They spoke to witnesses that claimed to have observed a Mokèlé-mbèmbé only two days before,[25] but they did not discover the animal themselves. However, they did return with what they believe to be a plaster cast of a Mokèlé-mbèmbé footprint.

2006: National Geographic

A May 2006 episode called "Super Snake" of the National Geographic series Dangerous Encounters included an expedition headed by Brady Barr to Lake Tele. No unknown animals were found.

2006: Vice Guide to Travel

In 2006, David Choe travelled to the Republic of Congo in search of the creature for Vice in the segment The Last Dinosaur of the Congo. Choe and his companions failed to find the animal and the focus of the documentary turned to the rituals of their Pygmy guides.[26]

2008: Destination Truth

In March 2008, an episode of the SyFy (formerly the SciFi Channel) series Destination Truth involved investigator Joshua Gates and crew searching for the creature. They did not visit the Likouala Region, which includes Lake Tele, but they visited Lake Bangweulu in Zambia instead, which had reports of a similar creature in the early 20th century, called the "'nsanga". The crew of Destination Truth kept calling the animal "Mokèlé-mbèmbé" to the locals, when that name is only used in the Republic of the Congo. The name used in that particular spot is "chipekwe". Their episode featured a videotaped encounter filmed from a great distance. On applying digital video enhancement techniques, the encounter proved to be nothing more than two submerged hippopotami.

2009: MonsterQuest

In March 2009 an episode of the History Channel series MonsterQuest involved William Gibbons, Rob Mullin, local guide Pierre Sima and a two-man film crew from White Wolf Productions. It took place in Cameroon, in the region of Dja River, Boumba River, and Nkogo River, near the border with the Republic of the Congo. The episode aired in the summer of 2009, and also featured an interview with Roy P. Mackal and Peter Beach of the Milt Marcy Expedition, 2006.[27] While no sightings were reported on the expedition, the team found evidence of a large underground cave with air vents. The team also received sonar readings of very long, serpentine shapes underwater.

2011: Beast Hunter

A March 2011 episode of Beast Hunter on the National Geographic Channel featured a search for Mokele-mbembe in the Congo Basin.[28][29]

2012: The Newmac Expedition

In April 2012 Stephen McCullah & Sam Newton launched a Kickstarter campaign to fund an expedition to the Congo region to search for Mokele-mbembe.[30][31] Despite raising around $29,000 the expedition suffered financial difficulties and is believed to have been abandoned shortly after the party reached the Congo in July 2012.[30][32][33]

In cryptozoology

According to science writer and cryptozoologist Willy Ley, while there are sufficient anecdotal accounts to suggest "that there is a large and dangerous animal hiding in the shallow waters and rivers of Central Africa", the body of evidence remains insufficient for any realistic conclusions to be drawn on what the Mokèlé-mbèmbé may be.[34]

According to the writings of biologist and cryptozoologist Roy Mackal, who mounted two unsuccessful expeditions to find it, it is unlikely that the Mokèlé-mbèmbé is a mammal or an amphibian, leaving a reptile as the only plausible candidate. Of all the living reptiles, Mackal argues that the iguana and the monitor lizards bear the closest resemblance to the Mokèlé-mbèmbé, though, at 15 to 30 feet (9.1 m) long, the Mokèlé-mbèmbé would exceed the size of any known living examples of such reptiles. Mackal believes the description of the Mokèlé-mbèmbé is "consistent with a small sauropod dinosaur".

Mackal also judged the existence of an undiscovered relict sauropod to be plausible on the grounds that there were large amounts of uninhabited and unexplored territory in the region where a creature might live,[10] and on the grounds that other large creatures such as elephants exist in the region, living in large open clearings (called "bai") as well as in thicker wooded areas.[2]

However, other researchers have argued against the existence of Mokele Mbembe. According to Daniel Loxton and Donald Prothero, the conventional image of Mokele Mbembe held by cryptozoologists such as Roy Mackal is based on an outdated image of sauropod dinosaurs from the early twentieth century. More recent discoveries indicate that most sauropods did not live in swampy areas and subsist on aquatic plants (as was long supposed), but instead lived in seasonally dry woodlands and ate tough conifers and cycads. Loxton and Prothero argue that the sauropod image of Mokele Mbembe reflects a confirmation bias which seeks to force ambiguous eyewitness accounts to support wishful thinking. These authors also point out that a surviving population of sauropods would leave behind skeletal remains like other large animals do, and that Africa's rich fossil record would contain sauropod bones younger than 65 million years old if a group of such had survived to the present. The absence of this evidence, despite several centuries of Western contact with the region, numerous expeditions in search of the animal, and periodic aerial and satellite surveillance, all of which have detected elephants and other large animals - but no sauropods - all argue against the existence of Mokele Mbembe.[35]

In popular culture

Several popular cultures have used the Mokele-Mbembe:

- The film Baby: Secret of the Lost Legend, starring William Katt, was released in 1985 and featured a family of Mokele-mbembe (referred to as Brontosaurs) living in Africa.

- The Mokele-mbembe was featured in The Secret Files of the Spy Dogs episode "Earnest." It is among the creatures that have been caught by Earnest Anyway.

- The film The Dinosaur Project, starring Richard Dillane, was released in 2012. The film featured the Mokele-mbembe as a Plesiosaurus.

- In May 2013 the Norwegian experimental music outfit Sturle Dagsland released a song entitled "Mokèlé-mbèmbé".[36]

- The Roland Smith novel Cryptid Hunters revolves around a search for the Mokèlé-mbèmbé and successful recovery of two of its eggs (the only known adult specimens having died beforehand) from the jungles of the Congo.

- Mokele-mbembe is one of six cryptids sought by comedian and journalist Dom Joly in his travel book Scary Monsters and Super Creeps.

See also

- Emela-ntouka

- Ngoubou

- Mbielu-Mbielu-Mbielu

- Nguma-monene

- Mušḫuššu

- Cryptid

- Living dinosaur

- Loch Ness Monster

- Lariosauro

- Nahuelito

References

- ↑ Regusters, Herman A. (1982). Munger, Ned, ed. "Mokele-Mbembe: An Investigation into Rumors Concerning a Strange Animal in the Republic of the Congo, 1981" (PDF). Munger Africana Library Notes. Pasadena: California Institute of Technology (64): 4. ISSN 0047-8350. OCLC 810484029. OL 12484505W. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2017.

In ... Lingala ... the animal is called 'mokele mbembe,' interpreted as 'one who stops the flow of rivers.'

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 (Clark 1993, p. )

- ↑ Carroll, Robert T. "mokele-mbembe". The Skeptic's Dictionary. John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ Congo, episode 2 of 4 ("Spirits of the Forest")

- ↑ (Ley 1966, p. 69)

- ↑ (Ley 1966, p. 70)

- ↑ (Coleman 2003, p. 216)

- ↑ "July 16-27, 1919 | UAiR: University of Arizona Institutional Repository". uair.library.arizona.edu. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ (Ley 1966, pp. 71–72)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 (Mackal 1987, p. )

- ↑ "Image: Iguanodon.jpg, (768 × 509 px)". web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ Gibbons, William J. "Was a Mokèlé-mbèmbé killed at Lake Tele?". Anomalist.com. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- ↑ Coleman, Loren (6 January 2006). "Mokèlé-mbèmbé's Rev. Eugene Thomas, 78, dies". Cryptomundo.com. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ "Image: mm1_3070.jpg, (400 × 264 px)". web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ "mokelepie.jpg". Archived from the original on 15 December 2009.

- 1 2 3 Gibbons, William J. "In Search Of the Congo Dinosaur". Institute for Creation Research.

- 1 2 (Nugent 1993, p. )

- ↑ "明日できるコトは今日やらない". h3.dion.ne.jp. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ "Image: 10.jpg, (313 × 233 px)". unknownexplorers.com. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ prexpage Archived 27 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hebblethwaite, Cornelia (28 December 2011). "The hunt for Mokele-mbembe: Congo's Loch Ness Monster". BBC. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ Kirk, John (9 April 2006). "The Ngoubou". Cryptomundo.com. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ "Mokele Mbembe". The British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ "Spirits of the Forest - min 45:00". BBC.

- ↑ Coleman, Loren (3 February 2006). "Mokèlé-mbèmbé Expedition Update". Cryptomundo.com. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ Cordes, Nancy; Lee, Rebecca (5 December 2006). "A "Vice" Vacation without leaving home". abc News. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ Coleman, Loren (2 March 2009). "Mokele-Mbembe Expedition II Departs". Cryptomundo.com. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ "Swamp Monster of the Congo". National Geographic. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ Burke, Bill (13 March 2011). "Pat Spain tracks monsters on ‘Beast Hunter’". Boston Herald. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- 1 2 Stephen McCullah. "Documentary Expedition to Congo- KILLER REWARDS!!!". Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ↑ idoubtit (15 April 2012). "Cryptozoology expedition to Congo is on Kickstarter (Updated: no scientists)". Doubtful News. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ↑ idoubtit (13 October 2012). "Whatever happened to the trip to the Congo to look for Mokele-mbembe?". Doubtful News. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ↑ Marrero, Joe (19 July 2012). "So what happened to the Newmac Expedition?". Joemarrero.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ↑ (Ley 1966, p. 74)

- ↑ Daniel Loxton; Donald R. Prothero (13 August 2013). Abominable Science: Origins of the Yeti, Nessie, and other Famous Cryptids. Columbia University Press. pp. 290–. ISBN 978-0-231-52681-4.

- ↑ Sparrow, Joe (7 May 2013). "Sturle Dagsland: Alien Nightclubs". AnNewBandADay. Com. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

Bibliography

- Clark, Jerome (1993). Unexplained! 347 Strange Sightings, Incredible Occurrences, and Puzzling Physical Phenomena. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 0-8103-9436-7.

- Coleman, Loren (2003). The Field Guide to Lake Monsters, Sea Serpents, and Other Mystery Denizens of the Deep. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher. ISBN 1-58542-252-5.

- Gibbons, William J. (2006). Missionaries And Monsters. Coachwhip Publications. ISBN 978-1930585249.

- Leal, M. E. (2004). The African rainforest during the Last Glacial Maximum, an archipelago of forests in a sea of grass. Wageningen: Wageningen University. ISBN 90-8504-037-X.

- Ley, Willy (1966). Exotic Zoology. New York: Capricorn Books. (trade paperback edition)

- Mackal, Roy P. (1987). A Living Dinosaur? In Search of Mokele-Mbembe. E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-08543-2.

- Ndanga, Alfred Jean-Paul (2000) 'Réflexion sur une légende de Bayanga: le Mokele-mbembe', in Zo, 3, 39-45.

- Nugent, Rory (1993). Drums along the Congo: on the trail of Mokele-Mbembe, the last living dinosaur. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-58707-7.

- O'Hanlon, Redmond (1997). No Mercy: A Journey Into the Heart of the Congo. Vintage Books (Random House). ISBN 0-679-73732-4.

- Regusters, H.A. (1982). "Mokele - Mbembe: an investigation into rumors concerning a strange animal in the Republic of the Congo, 1981" (PDF). Munger Africana library notes. Pasadena: California Institute of Technology (CIT). 64. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2011.

- Shuker, Karl P.N. (1995). In Search of Prehistoric Survivors. London: Blandford. ISBN 0-7137-2469-2.

- Sjögren, Bengt (1980). Berömda vidunder. Settern. ISBN 91-7586-023-6.(in Swedish)

External links

- African Pygmies Culture and mythology of pygmy peoples from the Congo River basin

- Episode 43 - "Crypt O’ Zoology: Dinosaurs in Africa!" of the Monster Talk podcast which features an interview with Dr. Donald Prothero about his involvement with the 2009 MonsterQuest expedition to find Mokele-Mbembe.

- Prothero, Donald (22 June 2011). "A Living Dinosaur in the Congo? (Part 1)". Skepticblog.org. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- Prothero, Donald (29 June 2011). "A Living Dinosaur in the Congo? (Part 2)". Skepticblog.org. Retrieved 1 June 2013.