Mojave Desert

| Mojave Desert Hayikwiir Mat'aar (Mojave)[1] | |

| Mohave Desert | |

| Desert | |

Calico Basin in Red Rock National Conservation Area near Las Vegas | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| States | California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona |

| Part of | North American Desert ecoregion[2] |

| Borders on | Great Basin Desert (north) Sonoran Desert (south) Colorado Plateau (east) Colorado Desert (south) |

| River | Mojave River |

| Coordinates | 35°0.5′N 115°28.5′W / 35.0083°N 115.4750°WCoordinates: 35°0.5′N 115°28.5′W / 35.0083°N 115.4750°W |

| Highest point | Charleston Peak 11,918 ft (3,633 m)[3] |

| - location | Spring Mountains |

| - coordinates | 36°10′11″N 117°05′21″W / 36.16972°N 117.08917°W |

| Lowest point | Badwater Basin −279 ft (−85 m)[4] |

| - location | Death Valley |

| - coordinates | 36°51′N 117°17′W / 36.850°N 117.283°W |

| Area | 124,000 km2 (47,877 sq mi) |

| Biome | Desert |

| Geology | Basin and Range Province |

| For public | Mojave National Preserve, National Parks (Death Valley, Joshua Tree, Zion, and Grand Canyon) |

| |

The Mojave Desert ( /moʊˈhɑːvi, mə-/,[5][6][7] mo-HAH-vee or mə-HAH-vee) is an arid rain-shadow desert and the driest desert in North America.[8] It is located in the southwestern United States, primarily within southeastern California and southern Nevada, and it occupies a total of 47,877 sq mi (124,000 km2). Very small areas also extend into Utah and Arizona.[9] Its boundaries are generally noted by the presence of Joshua trees, which are native only to the Mojave Desert and are considered an indicator species, and it is believed to support an additional 1,750 to 2,000 species of plants.[10] The central part of the desert is sparsely populated, while its peripheries support large communities such as San Bernardino, Las Vegas, Lancaster, Palmdale, Victorville, and St. George.

The Mojave Desert is bordered by the Great Basin Desert to its north[8] and the Sonoran Desert to its south and east.[8] Topographical boundaries include the Tehachapi Mountains to the west, and the San Gabriel Mountains and San Bernardino Mountains to the south. The mountain boundaries are distinct because they are outlined by the two largest faults in California – the San Andreas and Garlock faults. The Mojave Desert displays typical basin and range topography. Higher elevations above 2,000 ft (610 m)) in the Mojave are commonly referred to as the High Desert; however, Death Valley is the lowest elevation in North America at 280 ft (85 m) below sea level and is one of the Mojave Desert's more notorious places. It occupies less than 50,000 sq mi (130,000 km2), making it the smallest of the North American deserts.[8]

The Mojave Desert is often referred to as the "high desert", in contrast to the "low desert", the Sonoran Desert to the south. However, the Mojave Desert is generally lower than the Great Basin Desert to the north. The spelling Mojave originates from the Spanish language while the spelling Mohave comes from modern English. Both are used today, although the Mojave Tribal Nation officially uses the spelling Mojave; the word is a shortened form of Hamakhaave, their endonym in their native language, which means 'beside the water'.[11]

Climate

The Mojave Desert receives less than 13 in (330 mm) of rain a year and is generally between 2,000 and 5,000 feet (610 and 1,520 m) in elevation. The Mojave Desert also contains the Mojave National Preserve; as well as the lowest and hottest place in North America: Death Valley at 282 ft (86 m) below sea level; where the temperature often surpasses 120 °F (49 °C) from late June to early August. Zion National Park in Utah lies at the junction of the Mojave, the Great Basin Desert, and the Colorado Plateau. Despite its aridity, the Mojave (and particularly the Antelope Valley in its southwest) has long been a center of alfalfa production; fed by irrigation coming from groundwater and (in the 20th century) from the California Aqueduct.

The Mojave is a desert of temperature extremes and two distinct seasons. Winter months bring comfortable daytime temperatures, which dip precipitously to around 20 °F (−7 °C) on valley floors, and below 0 °F (−18 °C) at higher elevations. Storms moving from the Pacific Northwest can bring rain and in some places even snow. More often, the rain shadow created by the Sierra Nevada as well as mountain ranges within the desert such as the Spring Mountains, bring only clouds and wind. In longer periods between storm systems, winter temperatures in valleys can approach 80 °F (27 °C).

Spring weather continues to be influenced by Pacific storms, but rainfall is more widespread and occurs less frequently after April. By early June, it is rare for another Pacific storm to have a significant impact on the region's weather; and temperatures after the middle of May are normally above 90 °F (32 °C) and frequently above 100 °F (38 °C).

Summer weather is dominated by heat. Temperatures on valley floors can soar above 120 °F (49 °C) and above 130 °F (54 °C) at the lowest elevations. Low humidity, high temperatures, and low pressure, draw in moisture from the Gulf of Mexico creating thunderstorms across the desert southwest known as the North American monsoon. While the Mojave does not get nearly the amount of rainfall that the Sonoran desert to the south receives, monsoonal moisture will create thunderstorms as far west as California's Central Valley from mid-June through early September.

Autumn is generally pleasant, with one to two Pacific storm systems creating regional rain events. October is one of the driest and sunniest months in the Mojave; and temperatures usually remain between 70 °F (21 °C) and 90 °F (32 °C) on the valley floors.

After temperature, wind is the most significant weather phenomenon in the Mojave. Across the region windy days are common; and also common in areas near the transition between the Mojave and the California low valleys, including near Cajon Pass, Soledad Canyon and the Tehachapi areas. During the June Gloom, cooler air can be pushed out into the desert from Southern California. In Santa Ana wind events, hot air from the desert blows out into the Los Angeles basin and other coastal areas. Wind farms in these areas generate power from these winds.

The other major weather factor in the region is elevation. The highest peak within the Mojave is Charleston Peak at 11,918 feet (3,633 m);[3] while the Badwater Basin in Death Valley is 279 feet (85 m) below sea level.[4] Accordingly, temperature and precipitation ranges wildly in all seasons across the region.

The Mojave Desert has not historically supported a fire regime because of low fuel loads and connectivity. However, in the last few decades, invasive annual plants (e.g., Bromus spp., Schismus spp., Brassica spp.) have facilitated fire; which has significantly altered many areas of the desert.[12] At higher elevations, fire regimes are regular but infrequent.

| Climate data for Furnace Creek, Death Valley (Elevation −190 ft (−58 m)) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 88 (31) |

97 (36) |

102 (39) |

113 (45) |

122 (50) |

128 (53) |

134 (57) |

127 (53) |

123 (51) |

113 (45) |

98 (37) |

88 (31) |

134 (57) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 66.9 (19.4) |

73.3 (22.9) |

82.1 (27.8) |

90.5 (32.5) |

100.5 (38.1) |

109.9 (43.3) |

116.5 (46.9) |

114.7 (45.9) |

106.5 (41.4) |

92.8 (33.8) |

77.1 (25.1) |

65.2 (18.4) |

91.4 (33) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 40.0 (4.4) |

46.3 (7.9) |

54.8 (12.7) |

62.1 (16.7) |

72.7 (22.6) |

81.2 (27.3) |

88.0 (31.1) |

85.7 (29.8) |

75.6 (24.2) |

61.5 (16.4) |

48.1 (8.9) |

38.3 (3.5) |

62.9 (17.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 15 (−9) |

26 (−3) |

26 (−3) |

39 (4) |

46 (8) |

54 (12) |

67 (19) |

65 (18) |

55 (13) |

37 (3) |

30 (−1) |

22 (−6) |

15 (−9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.39 (9.9) |

0.51 (13) |

0.30 (7.6) |

0.12 (3) |

0.03 (0.8) |

0.05 (1.3) |

0.07 (1.8) |

0.13 (3.3) |

0.21 (5.3) |

0.07 (1.8) |

0.18 (4.6) |

0.30 (7.6) |

2.36 (59.9) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 217 | 226 | 279 | 330 | 372 | 390 | 403 | 372 | 330 | 310 | 210 | 186 | 3,625 |

| Source #1: NOAA 1981–2010 US Climate Normals [13] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: weather2travel | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Searchlight, Nevada. (Elevation 3,550 ft (1,080 m)) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 77 (25) |

81 (27) |

90 (32) |

94 (34) |

102 (39) |

110 (43) |

111 (44) |

110 (43) |

107 (42) |

98 (37) |

86 (30) |

75 (24) |

111 (44) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 53.7 (12.1) |

58.4 (14.7) |

65.0 (18.3) |

73.1 (22.8) |

82.5 (28.1) |

92.7 (33.7) |

97.6 (36.4) |

95.4 (35.2) |

89.0 (31.7) |

77.0 (25) |

63.6 (17.6) |

54.4 (12.4) |

75.2 (24) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 35.6 (2) |

38.3 (3.5) |

41.8 (5.4) |

48.0 (8.9) |

55.9 (13.3) |

64.8 (18.2) |

71.4 (21.9) |

69.6 (20.9) |

63.9 (17.7) |

53.9 (12.2) |

43.0 (6.1) |

36.4 (2.4) |

51.9 (11.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 7 (−14) |

11 (−12) |

20 (−7) |

27 (−3) |

30 (−1) |

40 (4) |

52 (11) |

51 (11) |

41 (5) |

23 (−5) |

15 (−9) |

8 (−13) |

7 (−14) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.92 (23.4) |

0.96 (24.4) |

0.77 (19.6) |

0.40 (10.2) |

0.20 (5.1) |

0.11 (2.8) |

0.91 (23.1) |

1.08 (27.4) |

0.61 (15.5) |

0.52 (13.2) |

0.43 (10.9) |

0.79 (20.1) |

7.70 (195.6) |

| Source: The Western Regional Climate Center[15] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Mount Charleston Lodge, Nevada. (Elevation 7,420 ft (2,260 m)) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 70 (21) |

69 (21) |

73 (23) |

79 (26) |

86 (30) |

93 (34) |

98 (37) |

93 (34) |

90 (32) |

83 (28) |

79 (26) |

69 (21) |

98 (37) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 44.0 (6.7) |

43.4 (6.3) |

48.8 (9.3) |

54.8 (12.7) |

64.4 (18) |

74.1 (23.4) |

79.4 (26.3) |

78.2 (25.7) |

71.7 (22.1) |

61.4 (16.3) |

51.6 (10.9) |

44.3 (6.8) |

59.7 (15.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 19.2 (−7.1) |

19.8 (−6.8) |

23.5 (−4.7) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

36.4 (2.4) |

44.1 (6.7) |

52.0 (11.1) |

50.6 (10.3) |

43.5 (6.4) |

34.5 (1.4) |

26.0 (−3.3) |

19.4 (−7) |

33.1 (0.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −11 (−24) |

−15 (−26) |

1 (−17) |

7 (−14) |

16 (−9) |

17 (−8) |

31 (−1) |

30 (−1) |

17 (−8) |

9 (−13) |

1 (−17) |

−18 (−28) |

−18 (−28) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.83 (71.9) |

3.51 (89.2) |

1.92 (48.8) |

1.23 (31.2) |

0.70 (17.8) |

0.29 (7.4) |

2.13 (54.1) |

1.89 (48) |

1.69 (42.9) |

1.96 (49.8) |

1.31 (33.3) |

3.61 (91.7) |

23.09 (586.5) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 18.2 (46.2) |

29.3 (74.4) |

13.2 (33.5) |

8.3 (21.1) |

1.0 (2.5) |

0.2 (0.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1.6 (4.1) |

5.2 (13.2) |

20.0 (50.8) |

97.1 (246.6) |

| Source: The Western Regional Climate Center[16] | |||||||||||||

Geography

The Mojave Desert is defined by numerous mountain ranges creating its xeric conditions. These ranges often create valleys, endorheic basins, salt pans, and seasonal saline lakes when precipitation is high enough. These mountain ranges and valleys are part of the Basin and Range province and the Great Basin; a geologic area of crustal thinning which pulls open valleys over millions of years. Most of the valleys are internally drained (endorheic basins), so all precipitation that falls within the valley does not eventually flow to the ocean. Some of the Mojave (toward the east, in and around the Colorado River/Virgin River Gorge) is within a different geographic domain called the Colorado Plateau. This area is known for its incised canyons, high mesas and plateaus, and flat strata; a unique geographic locality found nowhere else on earth.

Cities and regions

While the Mojave Desert itself is sparsely populated, it has increasingly become urbanized in recent years. The metropolitan areas include: Las Vegas, which is the largest city in the Mojave with a metropolitan population of around 2.3 million in 2015; St. George, the largest Utah city in the Mojave, is located at the convergence of the Mojave, Great Basin and Colorado Plateau making it the northeastern-most metropolitan area in the Mojave. Lancaster, the largest California city in the desert; and over 850,000 people live in areas of the Mojave attached to the Greater Los Angeles metropolitan area, including Palmdale and Lancaster, (referred to as the Antelope Valley), Victorville, Apple Valley and Hesperia (referred to as the Victor Valley) attached to the Inland Empire metropolitan area, the 14th largest in the nation.

Smaller cities or micropolitan areas in the Mojave Desert include Helendale, Lake Havasu City, Kingman, Laughlin, Bullhead City and Pahrump. All have experienced rapid population growth since 1990.

Towns with fewer than 30,000 people in the Mojave include: Barstow, Boron, California City, Helendale, Joshua Tree, Landers, Lone Pine, Lucerne Valley, Mojave, Needles, Nipton, Pioneertown, Randsburg, Ridgecrest, Rosamond, Yucca Valley and Twentynine Palms in California; Mesquite and Moapa Valley in Nevada; and Hurricane in Utah.

The California portion of the desert also contains Edwards Air Force Base and Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, noted for experimental aviation and weapons projects, and the largest Marine Corps base in the world at Twentynine Palms. The US Army also maintains Fort Irwin & the National Training Center (NTC) which is another major training area for the United States Military. Mojave airport is also home to a long term storage facility for large airplanes due to extremely dry non-corrosive weather conditions and a hard ground ideal for parking aircraft. The airport also houses the Air and Space Port and was one of the test centres for the Virgin Galactic Fleet.

The Mojave Desert contains a number of ghost towns, the most significant of these being the gold-mining town of Oatman, Arizona, the silver-mining town of Calico, California, and the old railroad depot of Kelso. Some of the other ghost towns are of the more modern variety, created when U.S. Route 66 (and the lesser-known U.S. Route 91) were abandoned in favor of the Interstates. The Mojave Desert is crossed by major highways Interstate 15, Interstate 40, U.S. Route 95, U.S. Route 395 and California State Route 58.

Other than the Colorado River on the eastern half of the Mojave, few long streams cross the desert. The Mojave River is an important source of water for the southern parts of the desert. The Amargosa River flows from the Great Basin Desert south to near Beatty, Nevada, then underground through Ash Meadows before returning to the surface near Shoshone, California, disappearing underground again a short while later and has its final outlet into the southern end of Death Valley. The riverbed passes under SR 127 near Dumont Dunes before turning north into Death Valley National Park.

The Mojave Desert is also home to the Devils Playground; about 40 miles (64 km) of dunes and salt flats going in a northwest-southeasterly direction. The Devils Playground is a part of the Mojave National Preserve and is located between the town of Baker, California and Providence Mountains. The Cronese Mountains are found within the Devils Playground.

Parks and tourism

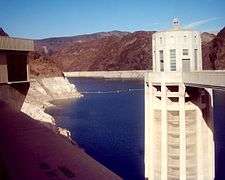

The Mojave Desert is one of the most popular tourism spots in North America, primarily because of the gambling destination of Las Vegas. The Mojave is also known for its scenic beauty, with three national parks – Death Valley National Park, Joshua Tree National Park, and the Mojave National Preserve. Lakes Mead, Mohave, and Havasu provide water sports recreation, and vast off-road areas entice off-road enthusiasts. The Mojave Desert also includes a California State Park, the Antelope Valley California Poppy Reserve, located in Lancaster. Hoover Dam is a popular tourist destination. Visitors get a chance to see the structure, the hydroelectric power plant, and hear the history of the dam's construction during the Great Depression.[17]

Besides the major national parks, there are other areas of identified significance and tourist interest in the desert such as the Big Morongo Canyon Preserve, within the Colorado Desert, and the Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, 17 miles (27 km) west of Las Vegas, both of which are managed by the Bureau of Land Management.

Among the more popular and unique tourist attractions in the Mojave is the self described world's tallest thermometer at 134 feet (41 m) high, which is located along Interstate 15 in Baker, California. The newly renovated Kelso Depot is the Visitor Center for the Mojave National Preserve. Nearby the massive Kelso Dunes are a popular recreation spot. Nipton, California, located on the northern entrance to the Mojave National Preserve, is a restored ghost town founded in 1885.

Several attractions and natural features are located in the Calico Mountains. Calico Ghost Town, in Yermo, is administered by San Bernardino County. The ghost town has several shops and attractions, and inspired Walter Knott to build Knott's Berry Farm. The BLM also administers Rainbow Basin and Owl Canyon, two "off-the-beaten-path" scenic attractions together north of Barstow in the Calicos. The Calico Early Man Site, in the Calico Hills east of Yermo, is believed by some archaeologists, including the late Louis Leakey, to show the earliest evidence with lithic stone tools found here of human activity in North America. The Calico Peaks scenically rise above all the destinations.

A tour of the Mojave Desert inspired American songwriter Carrie Jacobs-Bond to compose the parlor song "A Perfect Day" in 1909.[18]

Museums

- Antelope Valley Indian Museum State Historic Park

- Amargosa Opera House and Hotel

- Barstow Route 66 "Mother Road" Museum

- California Route 66 Museum

- Desert Discovery Center

- Harvey House Railroad Depot

- Kelso Depot, Restaurant and Employees Hotel

- Maturango Museum

- Mojave River Valley Museum

- Western America Railroad Museum

Parks and protected areas

- Antelope Valley California Poppy Reserve

- Arthur B. Ripley Desert Woodland State Park

- Death Valley National Park

- Desert National Wildlife Refuge (Nevada)

- Joshua Tree National Park

- Lake Mead National Recreation Area

- Mojave National Preserve

- Providence Mountains State Recreation Area

- Red Cliffs National Conservation Area (Utah)

- Red Rock Canyon State Park

- Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area (Nevada)

- Saddleback Butte State Park

- Snow Canyon State Park (Utah)

Flora

The flora of the Mojave Desert help define what is called the Mojave Desert in that the desert itself is generally considered to be outlined by the extent of growth of one of its plants, the Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia). Mojave Desert flora is not a vegetation type, although plants in the area have evolved in isolation because of physical barriers. This area includes southeastern California and smaller parts of central California, southern Nevada, southwestern Utah and northwestern Arizona in the United States. The flora are adapted to extremely hot and dry conditions, but generally not as extreme as the adaptations needed for survival in the flora of the Sonoran Desert, which has an overlap in its major flora, such as the creosote bush (Larrea tridentata).[19]

Black throated sparrow

- Bobcat

- Burrowing owl

- California kingsnake

- Chuckwalla

- Coachwhip

- Common raven

- Common side-blotched lizard

- Cottontail rabbit

- Cougar

- Coyote

- Desert bighorn sheep

- Desert chipmunk

- Desert horned lizard

- Desert iguana

- Desert kit fox

- Desert night lizard

- Desert tortoise

- Elf owl

- Fringe-toed lizard

Gambols quail

Great horned owl

- Hummingbird

- Jackrabbit

- Kangaroo rat

- Long-nosed leopard lizard

- Long-tailed brush lizard

- Mojave green rattlesnake

- Mojave ground squirrel

- Mohave tui chub

- Mule deer

- Pronghorn

- Red-spotted toad

- Red-tailed hawk

- Rosy boa

- Sidewinder rattler

- Tarantula

- Vole

- Western diamondback rattlesnake

- Western patch-nosed snake

- Zebra-tailed lizard

Soil and Plants Conditions

The soil types in the Mojave and Sonoran deserts are mostly derived from volcano, specifically the areas in California. As the topography goes down, particle sizes decreases as you move down the gradient, where you can also find low alkalinity. These erosional gradient is a habitat for many plant communities. As you go up the gradient of the desert, you will find more pediment and alluvial fans soil. In this areas, the flora is mostly succulents. As you move down the gradient, this area is described to be the upper and lower bajada, then you move into playa and salina, and finally you will reach the river. Drought deciduous plants are found in the alluvial fans and upper bajada. Evergreen perennials are found in some parts of the upper bajada, but it is mostly found in lower bajada. Once the salinity increases, you will find more salt-tolerant plants. In the river areas, deep-rooted plants reside. Due to the harsh and dry conditions in the desert, the plants have adapted to have succulent leaves, with CAM photosynthesis, spines, buried bulbs, hairy or waxy leaves, photosynthetic stems, deep tap roots, and ephemerals.

West Mojave Plan litigation

The U.S. Bureau of Land Management(BLM) manages public lands in the Mojave Desert as part of its "crown jewels of the American West" National Landscape Conservation System. It has designated numerous large off-road vehicle open use areas on public lands in the western Mojave Desert, including El Mirage, Jawbone Canyon, Rasor, Spangler Hills, Stoddard Valley, Dove Spring Canyon, Dumont Dunes, and the world's largest open off-road vehicle use area, Johnson Valley. Open areas designated for unrestricted vehicle travel in the western Mojave Desert total 363,480 acres (1,471.0 km2). Several additional open areas dedicated to unrestricted vehicle travel on public lands have been designated in the northern and eastern Colorado (NECO) Desert. In 2002, BLM designated all washes in the southeastern third of the NECO planning area as also open to unrestricted vehicle travel. This was followed in 2003 by BLM expanding the off-road vehicle network in the western Mojave Desert to enhance off-road vehicle recreation opportunity. In 2004, relative to the case of Center for Biological Diversity, et al., Plaintiffs, v. Bureau of Land Management, et al., Defendants; the United States District court enjoined "all off-road vehicle use in the washes of the NECO Desert planning area pending issuance of a new biological opinion.".[20]:a A new biological opinion was subsequently issued and BLM's open wash designation in the NECO planning area was reinstated. In 2006, several environmental groups protested an additional route network expansion designated under the West Mojave Desert (WEMO) plan.

In 2009, U.S. District Judge Susan Illston ruled against the BLM's proposed designation of additional off-road vehicle use allowance in the western Mojave Desert. According to the ruling, the BLM violated its own regulations[21] when it designated approximately 5,000 miles (8,000 km) of off-roading routes in 2006.[22] According to Judge Ilston, the BLM's designation was significantly "flawed because it does not contain a reasonable range of alternatives" to limit damage to sensitive habitat.[23] Judge Illston found that the bureau had inadequately analyzed the routes' impacts on air quality, soils, plant communities, riparian habitats, and sensitive species such as the endangered Mojave fringe-toed lizard, pointing out that the desert and its resources are "extremely fragile, easily scarred, and slowly healed."[23]

The court also found that the BLM failed to follow route designation procedures established in the agency’s own California Desert Conservation Area Plan, which allowed visitors to create hundreds of illegal OHV routes during the past three decades. The plan normally requires the BLM to consider the impacts to private property, non-motorized recreation opportunity, and natural resources before establishing off-road areas.[21] The adopted West Mojave plan amendment was found to have violated the BLM's own manual of regulations, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA) and the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA).[22] The ruling was considered a success for a coalition of conservation groups, including the California Native Plant Society, Friends of Juniper Flats, the Alliance for Responsible Recreation, Community Off-Road Vehicle Watch, The Center for Biological Diversity, Sierra Club, and The Wilderness Society, who together initiated the legal challenge in late 2006.[23]

In 2011, Judge Illston ruled on a remedy request submitted by the ten involved environmental organizations. BLM in this ruling was directed to complete a revised WEMO route designation complying with all laws and regulations by March 2014. The agency is also required per this ruling to place signs on all off-road vehicle routes which are legal to use, create a monitoring plan to determine if illegal vehicle use is occurring, and provide additional enforcement to prevent illegal use.[24]

Gallery

- lake in Badwater Basin, Death Valley National Park

- Church near Lancaster, California used as a filming location for Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill films, Vol. I & II (2003, 2004)

Where the San Bernardino Mountains meet the Mojave Desert

Where the San Bernardino Mountains meet the Mojave Desert- Sand blowing off a crest in the Kelso Dunes of the Mojave Desert

Lake Mead provides water for cities in Arizona, California, and Nevada

Lake Mead provides water for cities in Arizona, California, and Nevada- Pisgah Crater Lava tube SPJ, Between Barstow and Needles, California

- Skull Rock, a rock formation in Joshua Tree NP

Cholla cactus in bloom at night

Cholla cactus in bloom at night

Orange flowering barrel cactus is very common in the Mojave Desert.

Orange flowering barrel cactus is very common in the Mojave Desert. Moments after Dawn in Joshua Tree, California

Moments after Dawn in Joshua Tree, California- Creosote (Larrea tridentata) on alluvium at Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, southern Nevada.

See also

- Amboy Crater

- Bullhead City, Arizona

- Coso Rock Art District

- Death Valley National Park

- Deserts of California

- Fossil Falls

- Ivanpah Solar Power Facility

- Kelso Dunes

- List of California regions

- Mitchell Caverns

- Mohave Native Americans

- Mojave Air and Space Port

- Mojave Desert News

- Mojave Road

- Needles, California

- Pisgah Crater

- Shrub-steppe ecoregion

- Solar power plants in the Mojave Desert

- Trona Pinnacles

- Zzyzx, California

References

- ↑ Munro, P., et al. A Mojave Dictionary Los Angeles: UCLA, 1992

- ↑ Western Ecology Division, US Environmental Protection Agency

- 1 2 Stark, Lloyd R.; Whittemore, Alan T. (2000). "Bryophytes From the Northern Mojave Desert". Southwestern Naturalist. 45: 226–232. Archived from the original on 2003-06-12 – via Mosses of Nevada On-line.

- 1 2 "USGS National Elevation Dataset (NED) 1 meter Downloadable Data Collection from The National Map 3D Elevation Program (3DEP) – National Geospatial Data Asset (NGDA) National Elevation Data Set (NED)". United States Geological Survey. September 21, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach, James Hartmann and Jane Setter, eds., English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- ↑ "Mojave". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- ↑ "Mojave". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 4 Mojave Desert Wildflowers, Pam MacKay, 2nd Ed. 2013, p. 1

- ↑ "Mojave desert Map".

- ↑ Mazzucchelli, Vincent G., "The Southern Limits of the Mohave Desert, California", The California Geographer, 1967, VIII: 127–133. This study provides original maps of the Mohave and adjacent deserts in the southwestern states.

- ↑ "American Indian History".

- ↑ Brooks, Matthew L. (2002-08-01). "Peak Fire Temperatures and Effects on Annual Plants in the Mojave Desert". Ecological Applications. 12 (4): 1088–1102. ISSN 1939-5582. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2002)012[1088:PFTAEO]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ NOAA. "1981–2010 US Climate Normals". NOAA. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ↑ Weather2travel.com. "Weather2travel Death Valley Climate". Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- ↑ "Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Information". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Information". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Hoover Dam". General Contractor Bob Moore Construction Company. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ Reublein, Rick. "America's first great woman popular song composer" site.

- ↑ Shreve, Forrest; Wiggins, Ira Loren (1964-01-01). Vegetation and Flora of the Sonoran Desert. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804701631.

- ↑ "Desert Lawsuit Settlement". California Desert District. Bureau of Land Management. April 27, 2007. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

a. "Order Re: Defendants' motion to alter or amend the judgment and plaintiffs' motion for injunctive relief" (PDF). United States District Court for the Northern District of California. December 20, 2004. Retrieved 2010-01-12. - 1 2 Mojave’s Off-Highway Roads Found Illegal

- 1 2 Judge rejects federal plan for SoCal desert routes

- 1 2 3 Judge rejects U.S. management plan for California desert, Los Angeles Times, 30 September 2009.

- ↑ Danelski, David (31 January 2011). "Judge: Redo off-roading routes in Mojave Desert". Press-Enterprise.

Further reading

- Miller, D.M. and Amoroso, L. (2007). Preliminary surficial geology of the Dove Spring off-highway vehicle open area, Mojave Desert, California [U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2006-1265]. Reston, VA: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- Mojave Desert Wildflowers, Jon Mark Stewart, 1998, pg. iv

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mojave Desert. |

- The Nature Explorers Mojave Desert Expedition 1 Hour 27 minute ecosystem video in July.

- Mojave Desert images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu

- Mojave Desert Blog

- Mojave Desert Catalog Project

- Community ORV Watch

Media related to Nature of the Mojave Desert at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nature of the Mojave Desert at Wikimedia Commons Mojave Desert travel guide from Wikivoyage

Mojave Desert travel guide from Wikivoyage