Icelandic language

| Icelandic | |

|---|---|

| íslenska | |

| Pronunciation | ['iːs(t)lɛnska] |

| Native to | Iceland |

Native speakers | 331,000 (2013)[1] |

|

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

|

Latin (Icelandic alphabet) Icelandic Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by | Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies in an advisory capacity |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

is |

| ISO 639-2 |

ice (B) isl (T) |

| ISO 639-3 |

isl |

| Glottolog |

icel1247[2] |

| Linguasphere |

52-AAA-aa |

|

The Icelandic-speaking world: regions where Icelandic is the language of the majority regions where Icelandic is the language of a significant minority | |

Icelandic /aɪsˈlændɪk/ (Icelandic: íslenska, pronounced ['iːs(t)lɛnska]) is a North Germanic language, the language of Iceland. It is an Indo-European language belonging to the North Germanic or Nordic branch of the Germanic languages. Historically, it was the westernmost of the Indo-European languages prior to the colonisation of the Americas. Icelandic, Faroese, Norn, and Western Norwegian formerly constituted West Nordic; Danish, Eastern Norwegian and Swedish constituted East Nordic. Modern Norwegian Bokmål is influenced by both groups, leading the Nordic languages to be divided into mainland Scandinavian languages and Insular Nordic (including Icelandic).

Most Western European languages have greatly reduced levels of inflection, particularly noun declension. In contrast, Icelandic retains a four-case synthetic grammar comparable to, but considerably more conservative and synthetic than, German. Because Icelandic is in the Germanic family, which as a whole reduced the Indo-European case system, it is inappropriate to compare the grammar of Icelandic to that of the more conservative Baltic and Slavic languages of the Indo-European family, many of which retain six or more cases. Icelandic is distinguished by a wide assortment of irregular declensions. Icelandic also has many instances of oblique cases without any governing word, much like Latin. For example, many of the various Latin ablatives have a corresponding Icelandic dative. The conservatism of the Icelandic language and its resultant near-isomorphism to Old Norse (which is equivalently termed Old Icelandic by linguists) means that modern Icelanders can easily read the Eddas, sagas, and other classic Old Norse literary works created in the tenth through thirteenth centuries.

The vast majority of Icelandic speakers—about 320,000—live in Iceland. More than 8,000 Icelandic speakers live in Denmark,[3] of whom approximately 3,000 are students.[4] The language is also spoken by some 5,000 people in the United States[5] and by more than 1,400 people in Canada,[6] notably in the province of Manitoba.

While 97% of the population of Iceland consider Icelandic their mother tongue,[7] the language is in decline in some communities outside Iceland, particularly in Canada. Icelandic speakers outside Iceland represent recent emigration in almost all cases except Gimli, Manitoba, which was settled from the 1880s onwards.

The state-funded Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies serves as a centre for preserving the medieval Icelandic manuscripts and studying the language and its literature. The Icelandic Language Council, comprising representatives of universities, the arts, journalists, teachers, and the Ministry of Culture, Science and Education, advises the authorities on language policy. Since 1995, on 16 November each year, the birthday of 19th-century poet Jónas Hallgrímsson is celebrated as Icelandic Language Day.[7][8]

History

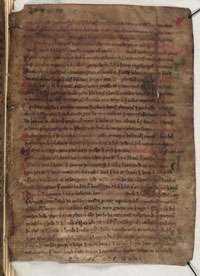

The oldest preserved texts in Icelandic were written around 1100 AD. Much of the texts are based on poetry and laws traditionally preserved orally. The most famous of the texts, which were written in Iceland from the 12th century onward, are the Icelandic Sagas. They comprise the historical works and the eddaic poems.

The language of the sagas is Old Icelandic, a western dialect of Old Norse. Danish rule of Iceland from 1380 to 1918 had little effect on the evolution of Icelandic, which remained in daily use among the general population. Though more archaic than the other living Germanic languages, Icelandic changed markedly in pronunciation from the 12th to the 16th century, especially in vowels (in particular, á, æ, au, and y/ý).

The modern Icelandic alphabet has developed from a standard established in the 19th century, primarily by the Danish linguist Rasmus Rask. It is based strongly on an orthography laid out in the early 12th century by a mysterious document referred to as The First Grammatical Treatise by an anonymous author, who has later been referred to as the First Grammarian. The later Rasmus Rask standard was a re-creation of the old treatise, with some changes to fit concurrent Germanic conventions, such as the exclusive use of k rather than c. Various archaic features, as the letter ð, had not been used much in later centuries. Rask's standard constituted a major change in practice. Later 20th-century changes include the use of é instead of je and the removal of z from the Icelandic alphabet in 1973.[9]

Apart from the addition of new vocabulary, written Icelandic has not changed substantially since the 11th century, when the first texts were written on vellum.[10] Modern speakers can understand the original sagas and Eddas which were written about eight hundred years ago. The sagas are usually read with updated modern spelling and footnotes but otherwise intact (as with modern English readers of Shakespeare). With some effort, many Icelanders can also understand the original manuscripts.

Legal status and recognition

According to an act (61/2011) passed by parliament in 2011, Icelandic is "the official language in Iceland".[11]

Iceland is a member of the Nordic Council, a forum for co-operation between the Nordic countries, but it uses only Danish, Norwegian and Swedish as its working languages (although the Council does publish material in Icelandic).[12] Under the Nordic Language Convention, since 1987 Icelandic citizens have had the right to use Icelandic when interacting with official bodies in other Nordic countries, without becoming liable for any interpretation or translation costs. The Convention covers visits to hospitals, job centres, the police and social security offices.[13][14] It does not have much effect since it is not very well known, and because those Icelanders not proficient in the other Scandinavian languages often have a sufficient grasp of English to communicate with institutions in that language (although there is evidence that the general English skills of Icelanders have been somewhat overestimated).[15] The Nordic countries have committed to providing services in various languages to each other’s citizens, but this does not amount to any absolute rights being granted, except as regards criminal and court matters.[16][17]

Phonology

Icelandic has very minor dialectal differences phonetically. The language has both monophthongs and diphthongs, and consonants can be voiced or unvoiced.

Voice plays a primary role in the differentiation of most consonants including the nasals but excluding the plosives. The plosives b, d, and g are voiceless and differ from p, t and k only by their lack of aspiration. Preaspiration occurs before geminate (long or double consonants) p, t and k. It does not occur before geminate b, d or g. Pre-aspirated tt is analogous etymologically and phonetically to German and Dutch cht (compare Icelandic nótt, dóttir with the German Nacht, Tochter and the Dutch nacht, dochter).

Consonants

| Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | (m̥) | m | (n̥) | n | (ɲ̊) | (ɲ) | (ŋ̊) | (ŋ) | ||

| Stop | pʰ | p | tʰ | t | (cʰ) | (c) | kʰ | k | ||

| Continuant | sibilant | s | ||||||||

| non-sibilant | f | v | θ | (ð) | (ç) | j | (x) | (ɣ) | h | |

| Lateral | (l̥) | l | ||||||||

| Rhotic | (r̥) | r | ||||||||

- /n̥ n tʰ t/ are laminal denti-alveolar, /s/ is apical alveolar,[18][19] /θ ð/ are alveolar non-sibilant fricatives;[19][20] the former is laminal,[19][20] while the latter is usually apical.[19][20]

- The voiceless continuants /f s θ ç x h/ are always constrictive [f s̺ θ̠ ç x h], but the voiced continuants /v ð j ɣ/ are not very constrictive and are often closer to approximants [ʋ ð̠˕ j ɰ] than fricatives [v ð̠ ʝ ɣ].

- The rhotic consonants may either be trills [r̥ r] or taps [ɾ̥ ɾ], depending on the speaker.

- A phonetic analysis reveals that the voiceless lateral approximant [l̥] is, in practice, usually realized with considerable friction, especially word-finally or syllable-finally, i. e., essentially as a voiceless alveolar lateral fricative [ɬ].[21]

Scholten (2000, p. 22) includes three extra phones: [ʔ l̥ˠ lˠ].

A large number of competing analyses have been proposed for Icelandic phonemes. The problems stem from complex but regular alternations and mergers among the above phones in various positions.

Vowels

| Front | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| plain | round | ||

| Close | i | u | |

| Near-close | ɪ | ʏ | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | œ | ɔ |

| Open | a | ||

| Front offglide |

Back offglide | |

|---|---|---|

| Mid | ei • øi | ou |

| Open | ai | au |

Grammar

Icelandic retains many grammatical features of other ancient Germanic languages, and resembles Old Norwegian before much of its fusional inflection was lost. Modern Icelandic is still a heavily inflected language with four cases: nominative, accusative, dative and genitive. Icelandic nouns can have one of three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine or neuter. There are two main declension paradigms for each gender: strong and weak nouns, which are, furthermore, divided in subclasses of nouns, based primarily on the genitive singular and nominative plural ending of a particular noun. For example, within the masculine nouns that have a strong declension, there is a subclass (class 1) that declines with an -s (Hests) in the genitive singular and -ar (Hestar) in the nominative plural. However, there is another subclass (class 3) of strong masculine nouns that always declines with -ar (Hlutar) in the genitive singular and -ir (Hlutir) in the nominative plural. Additionally, Icelandic permits a quirky subject, which is a phenomenon in which certain verbs specify that their subjects are to be in a case other than the nominative.

Nouns, adjectives and pronouns are declined in the four cases and for number in the singular and plural. T-V distinction (þérun) in modern Icelandic seems on the verge of extinction, yet it can still be found, especially in structured official address and traditional phrases.

Verbs are conjugated for tense, mood, person, number and voice. There are three voices: active, passive and middle (or medial), but it may be debated whether the middle voice is a voice or simply an independent class of verbs of its own (because every middle-voice verb has an active ancestor but concomitant are sometimes drastic changes in meaning and the fact that the middle-voice verbs form a conjugation group of their own). Examples might be koma ("come") vs. komast ("get there"), drepa ("kill") vs. drepast ("perish ignominiously") and taka ("take") vs. takast ("manage to"). In every case mentioned, the meaning has been so altered, that one can hardly see them as the same verb in different voices. Verbs have up to ten tenses, but Icelandic, like English, forms most of them with auxiliary verbs. There are three or four main groups of weak verbs in Icelandic, depending on whether one takes a historical or a formalistic view: -a, -i, and -ur, referring to the endings that these verbs take when conjugated in the first person singular present. Some Icelandic infinitives end with the -ja suffix, some with á, two with u (munu, skulu) one with o (þvo: "wash") and one with e (the Danish borrowing ske which is probably withdrawing its presence). For many verbs that require an object, a reflexive pronoun can be used instead. The case of the pronoun depends on the case that the verb governs. As for further classification of verbs, Icelandic behaves much like other Germanic languages, with a main division between weak verbs and strong, and the class of strong verbs, few as they may be (c. 150–200), is divided into six plus reduplicative verbs. They still make up some of the most frequently used verbs. (Að vera, "to be", is the example par excellence, having two subjunctives and two imperatives in addition to being made up of different stems.) There is also a class of auxiliary verbs, called the -ri verbs (4 or 5, depending who is counting) and then the oddity að valda ("to cause"), called the only totally irregular verb in Icelandic although every form of it is caused by common and regular sound changes.

The basic word order in Icelandic is subject–verb–object. However, as words are heavily inflected, the word order is fairly flexible, and every combination may occur in poetry; SVO, SOV, VSO, VOS, OSV and OVS are all allowed for metrical purposes. However, as with most Germanic languages, Icelandic usually complies with the V2 word order restriction, so the conjugated verb in Icelandic usually appears as the second element in the clause, preceded by the word or phrase being emphasized. For example:

- Ég veit það ekki. (I know that not.)

- Ekki veit ég það. (Not know I that. )

- Það veit ég ekki. (That know I not.)

- Ég fór til Bretlands þegar ég var eins árs. (I went to Britain when I was one year old.)

- Til Bretlands fór ég þegar ég var eins árs. (To Britain went I, when I was one year old.)

- Þegar ég var eins árs fór ég til Bretlands. (When I was one year old, went I to Britain.)

In the above examples, the conjugated verbs veit and fór are always the second element in their respective clauses.

Vocabulary

Early Icelandic vocabulary was largely Old Norse. The introduction of Christianity to Iceland in the 11th century brought with it a need to describe new religious concepts. The majority of new words were taken from other Scandinavian languages; kirkja ("church"), for example. Numerous other languages have had their influence on Icelandic: French brought many words related to the court and knightship; words in the semantic field of trade and commerce have been borrowed from Low German because of trade connections. In the late 18th century, language purism began to gain noticeable ground in Iceland and since the early 19th century it has been the linguistic policy of the country (see linguistic purism in Icelandic). Nowadays, it is common practice to coin new compound words from Icelandic derivatives.

Icelandic personal names are patronymic (and sometimes matronymic) in that they reflect the immediate father or mother of the child and not the historic family lineage. This system—which was formerly used throughout the Nordic area and beyond—differs from most Western family name systems.

Linguistic purism

During the 18th century, a movement was started by writers and other educated people of the country to rid the language of foreign words as much as possible and to create a new vocabulary and adapt the Icelandic language to the evolution of new concepts, and thus not having to resort to borrowed neologisms as in many other languages. Many old words which had fallen into disuse were recycled and given new senses in the modern language, and neologisms were created from Old Norse roots. For example, the word rafmagn ("electricity"), literally means "amber power", calquing the derivation of the international root "electr-" from Greek elektron ("amber"). Similarly, the word sími ("telephone") originally meant "cord", and tölva ("computer") is a portmanteau of tala ("digit; number") and völva ("seeress").

Writing system

The Icelandic alphabet is notable for its retention of two old letters which no longer exist in the English alphabet: Þ, þ (þorn, modern English "thorn") and Ð, ð (eð, anglicised as "eth" or "edh"), representing the voiceless and voiced "th" sounds (as in English thin and this), respectively. The complete Icelandic alphabet is:

| Majuscule forms (also called uppercase or capital letters) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Á | B | D | Ð | E | É | F | G | H | I | Í | J | K | L | M | N | O | Ó | P | R | S | T | U | Ú | V | X | Y | Ý | Þ | Æ | Ö |

| Minuscule forms (also called lowercase or small letters) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | á | b | d | ð | e | é | f | g | h | i | í | j | k | l | m | n | o | ó | p | r | s | t | u | ú | v | x | y | ý | þ | æ | ö |

The letters with diacritics, such as á and ö, are for the most part treated as separate letters and not variants of their derivative vowels. The letter é officially replaced je in 1929, although it had been used in early manuscripts (until the 14th century) and again periodically from the 18th century.[22] The letter z, which had been a part of the Icelandic alphabet for a long time but was no longer distinguished from s in pronunciation, was officially removed in 1973.

Cognates with English

As Icelandic shares its ancestry with English and both are Germanic languages, there are many cognate words in both languages; each have the same or a similar meaning and are derived from a common root. The possessive, though not the plural, of a noun is often signified with the ending -s, as in English. Phonological and orthographical changes in each of the languages will have changed spelling and pronunciation. But a few examples are given below.

| English word | Icelandic word | Spoken comparison |

|---|---|---|

| apple | epli | |

| book | bók | |

| high/hair | hár | |

| house | hús | |

| mother | móðir | |

| night | nótt | |

| stone | steinn | |

| that | það | |

| word | orð | |

See also

- Basque–Icelandic pidgin (a pidgin that was used to trade with Basque whalers)

- Icelandic Encyclopedia A-Ö

- Icelandic exonyms

- Icelandic literature

- Icelandic name

References

- ↑ 97% of a population of 325,000 + 15,000 native Icelandic speakers outside Iceland

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Icelandic". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Statbank Danish statistics

- ↑ Official Iceland website

- ↑ "Icelandic". MLA Language Map Data Center. Modern Language Association. Retrieved 2010-04-17. Based on 2000 US census data.

- ↑ Canadian census 2011

- 1 2 "Icelandic: At Once Ancient And Modern" (PDF). Icelandic Ministry of Education, Science and Culture. 2001. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ↑ "Menntamálaráðuneyti" [Ministry of Education]. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ↑ "Auglýsing um afnám Z" [Advertising on the Elimination of Z]. Brunnur.stjr.is. 2000-04-03. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ Sanders, Ruth (2010). German: Biography of a Language. Oxford University Press. p. 209.

Overall, written Icelandic has changed little since the eleventh century Icelandic sagas, or historical epics; only the addition of significant numbers of vocabulary items in modern times makes it likely that a saga author would have difficulty understanding the news in today's [Icelandic newspapers].

- ↑ "Act [No 61/2011] on the status of the Icelandic language and Icelandic sign language" (PDF). Ministry of Education, Science and Culture. p. 1. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

Article 1; National language – official language; Icelandic is the national language of the Icelandic people and the official language in Iceland.

- ↑ "Norden". Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ↑ "Nordic Language Convention". Archived from the original on 2007-06-29. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ↑ "Nordic Language Convention". Archived from the original on 2009-04-28. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ↑ Robert Berman. "The English Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency of Icelandic students, and how to improve it".

English is often described as being almost a “second language” in Iceland, as opposed to a “foreign language” like German or Chinese. Certainly in terms of Icelandic students’ Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS), English does indeed seem to be a second language. However, in terms of many Icelandic students’ Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP)—the language skills required for success in school—evidence will be presented suggesting that there may be a large number of students who have substantial trouble utilizing these skills.

- ↑ Language Convention not working properly Archived 2009-04-28 at the Wayback Machine., Nordic news, March 3, 2007. Retrieved on April 25, 2007.

- ↑ Helge Niska, "Community interpreting in Sweden: A short presentation", International Federation of Translators, 2004. Retrieved on April 25, 2007.

- ↑ Kress (1982:23–24) "It's never voiced, as s in sausen, and it's pronounced by pressing the tip of the tongue against the alveolar ridge, close to the upper teeth – somewhat below the place of articulation of the German sch. The difference is that German sch is labialized, while Icelandic s is not. It's a pre-alveolar, coronal, voiceless spirant."

- 1 2 3 4 Pétursson (1971:?), cited in Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996:145)

- 1 2 3 Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996:144–145)

- ↑ Liberman, Mark. "A little Icelandic phonetics". Language Log. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ (in Icelandic) Hvenær var bókstafurinn 'é' tekinn upp í íslensku í stað 'je' og af hverju er 'je' enn notað í ýmsum orðum? (retrieved on 2007-06-20)

Bibliography

- Árnason, Kristján; Sigrún Helgadóttir (1991). "Terminology and Icelandic Language Policy". Behovet och nyttan av terminologiskt arbete på 90-talet. Nordterm 5. Nordterm-symposium. pp. 7–21.

- Halldórsson, Halldór (1979). "Icelandic Purism and its History". Word. 30: 76–86.

- Kress, Bruno (1982), Isländische Grammatik, VEB Verlag Enzyklopädie Leipzig

- Kvaran, Guðrún; Höskuldur Þráinsson; Kristján Árnason; et al. (2005). Íslensk tunga I–III. Reykjavík: Almenna bókafélagið. ISBN 9979-2-1900-9. OCLC 71365446.

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19814-8.

- Orešnik, Janez; Magnús Pétursson (1977). "Quantity in Modern Icelandic". Arkiv för Nordisk Filologi. 92: 155–71.

- Pétursson, Magnus (1971), "Étude de la réalisation des consonnes islandaises þ, ð, s, dans la prononciation d'un sujet islandais à partir de la radiocinématographie" [Study on the realisation of the Icelandic consonants þ, ð, s, in the pronunciation of an Icelandic subject from radiocinematography], Phonetica, 33: 203–216, doi:10.1159/000259344

- Rögnvaldsson, Eiríkur (1993). Íslensk hljóðkerfisfræði [Icelandic phonology]. Reykjavík: Málvísindastofnun Háskóla Íslands. ISBN 9979-853-14-X.

- Scholten, Daniel (2000). Einführung in die isländische Grammatik. Munich: Philyra Verlag. ISBN 3-935267-00-2. OCLC 76178278.

- Vikør, Lars S. (1993). The Nordic Languages. Their Status and Interrelations. Oslo: Novus Press. pp. 55–59, 168–169, 209–214.

Further reading

- Icelandic: Grammar, Text and Glossary (1945; 2000) by Stefán Einarsson. Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 9780801863578.

External links

| Icelandic edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- The Icelandic Language, an overview of the language from the Icelandic Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- BBC Languages – Icelandic, with audio samples

- Icelandic: at once ancient and modern, a 16-page pamphlet with an overview of the language from the Icelandic Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, 2001.

- Íslensk málstöð (The Icelandic Language Institute)

- (in Icelandic) Lexicographical Institute of Háskóli Íslands / Orðabók Háskóla Íslands

Dictionaries

- Icelandic-English Dictionary / Íslensk-ensk orðabók Sverrir Hólmarsson, Christopher Sanders, John Tucker. Searchable dictionary from the University of Wisconsin–Madison Libraries

- Icelandic – English Dictionary: from Webster's Rosetta Edition.

- Collection of Icelandic bilingual dictionaries

- Old Icelandic-English Dictionary by Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson