Bookmobile

A bookmobile or mobile library is a vehicle designed for use as a library. It is designed to hold books on shelves in such a way that when the vehicle is parked they can be accessed by readers. Mobile libraries are often used to provide library services to villages and city suburbs that otherwise do not have access to a local or neighborhood branch library. They can also service groups or individuals who have difficulty accessing libraries, for example, occupants of retirement homes. As well as regular books, a bookmobile might also carry large print books, audiobooks, other media, IT equipment, and Internet access.

History

19th century

The British Workman reported in 1857[1] about a perambulating library operating in a circle of eight villages, in Cumbria. A Victorian merchant and philanthropist, George Moore, had created the project to "diffuse good literature among the rural population".[2]

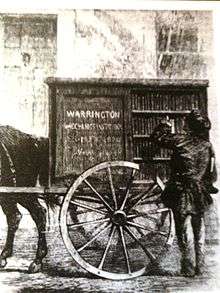

The Warrington Perambulating Library, set up in 1858, was another early British mobile library. This horse-drawn van was operated by the Warrington Mechanics' Institute, which aimed to increase the lending of its books to enthusiastic local patrons.[3]

Fairfax County, Virginia had a bookmobile operating in the northwestern part of the county in 1890. County-wide bookmobile service was begun in 1940, in a truck loaned by the Works Progress Administration ("WPA"). The WPA support of the bookmobile ended in 1942, but the service did not.[4]

20th century

.jpg)

An early bookmobile in the United States was created in 1904 by the People's Free Library of Chester County, South Carolina, which served rural areas with a mule-drawn wagon carrying wooden boxes of books.[5]

Another early American bookmobile was developed by Mary Lemist Titcomb[6] (1857–1932).[7] As a librarian at the Washington County, Maryland Free Library, Titcomb was concerned that the library was not reaching all the people it could. The annual report for 1902 lists "23 branches", i.e., collections of 50 books in a case placed in stores and post offices around the county.[8] Realizing this still failed to reach all of the county's rural residents, in 1905 the Washington County Free Library provided one of the first American book wagons to residents by taking the books directly to their homes in remote parts of the county.[9]

Sarah Byrd Askew, a pioneering public librarian, was also an early developer of the bookmobile, driving her Ford Model T outfitted with a book collection to rural areas in New Jersey, beginning in 1920.[10]

The Hennepin County Public Library (Minneapolis) started operating a bookmobile (then called a book wagon) in 1923.[11]

During the Works Progress Administration days of 1936-1943, horse mounted librarians (known as "packhorse librarians") traveled the remote coves and mountainsides of Kentucky and nearby Appalachia bringing books and similar supplies to those who could not make the trip to a library on their own. Sometimes they relied on a centralized contact to help them distribute the materials.[12]

The "Library in Action" was a late-1960s Bronx, NY, program aiming to bring books to teenagers of color in under-served neighborhoods.[13]

Bookmobiles reached their height of popularity in the mid-twentieth century.

21st century

.jpg)

Bookmobiles are still in use, operated by libraries, schools, activists, and other organizations. Although some feel the bookmobile is an outmoded service, giving reasons like high costs, advanced technology, impracticality, and ineffectiveness, others cite the ability of the bookmobile to be more cost-efficient than building more branch libraries would be and its high use among its patrons as support for its continuation.[15] To meet the growing demand for "greener" bookmobiles that deliver outreach services to their patrons, some bookmobile manufacturers have introduced significant advances to reduce their carbon footprint, such as solar/battery solutions in lieu of traditional generators, and all-electric and hybrid-electric chassis.

The Internet Archive runs its own bookmobile to print out-of-copyright books on demand.[16] The project has spun off similar efforts elsewhere in the developing world.[17]

National Bookmobile Day

In the U.S., the American Library Association sponsors an annual National Bookmobile Day annually, on the Wednesday of National Library Week, in April.[18][19]

Present-day mobile libraries

Bookmobiles and similar services are used in many countries, in some locations without a vehicle (mainly in the developing world). Some examples include:

Africa

- A Camel Library Service in Kenya is funded by the Kenyan government and as a charity in Garissa and Wajir, near the border with Somalia. The service started with three camels in October 1996 and had 12 in 2006, delivering 7000 books,[20] daily, in English, Somali, and Swahili.[21] Masha Hamilton used this service as a background for her novel The Camel Bookmobile (2007).[22]

- A donkey-drawn mobile library in Zimbabwe not only delivers books but access to the Internet and multimedia, as well.[23]

Asia

- In Indonesia, Ridwan Sururi and his horse, named Luna, started a mobile library called Kudapustaka (meaning "horse library" in Indonesian). The goal is to help improve access to books for villagers in a region that has more than 977,000 illiterate adults. They travel between villages in central Java with books balanced on Luna's back. Sururi also visits schools three times a week.[24]

- In Thailand, many types of mobile libraries distribute books, IT equipment, and services:

- Elephant Libraries are used to take books, and IT equipment and services, to remote villages that have no other library service; this project was awarded the UNESCO literacy prize for 2002.

- Mobile libraries are also operated via Book Houses ("standard 3m x 6m freight containers fitted out as a library with books"); on buses; via floating libraries that offer books, educational facilities, and in some cases computers aboard book-boats that service riverside communities;[25]

- A Library Train for Homeless Children, parked in a siding near the railway police compound is a "joint project with the railway police in an initiative to keep homeless children from crime and exploitation by channeling them to more constructive activities". It is being replicated in "a slum community in Bangkok, also, via "a three vehicle set up", comprising a library carriage, a classroom carriage, and a computer and music room carriage.[25]

Europe

At the 2002 IFLA MobileMeet in Glasgow, Scotland: "There were mobiles from Sweden, Holland Ireland, England and of course Scotland. There were big vans from Edinburgh and small vans from the Highlands. Many of the vans were proudly carrying awards from previous meets."[25]

- The Epos library ship serves many small communities in Western Norway.

- The Mobile Library Katarina Jee in Estonia has been running since 2008 serving patrons in suburbs of Tallinn.

- Madrid, Spain operates a bibliobus program, with books, DVDs, CDs and other material.[26] which has also been involved in the Puente de Colores community development project.[27]

- In some areas of the United Kingdom (mostly rural Scotland and Wales), mobile banks and post offices are run using converted vans.[28]

North America

.jpg)

- On the ground programs

- Books on Bikes is a pilot program by the Seattle Public Library using a customized trailer pulled by pedal power to bring library services to community events in Seattle.[29]

- Street Books, in Portland, Oregon, USA, is a nonprofit book service that travels via bicycle-powered cart to lend books to “people living outside”.[30]

- Volusia County's Book Bike, the Library Cruiser, debuted in September 2015 where it was ridden to various places in that Florida county, offering WiFi, help utilizing the ebook collection, information about obtaining a library card, and books available to check out.[31]

- Online programs

- The Internet Archive's bookmobile program is discussed above.

- Social media programs

- The social media sites bookmobility.org,[32] HASTAC,[33] and Pinterest include many posts about bookmobiles and related initiatives, past and present.[34]

Oceania

- In Australia, "lots of Australian mobiles [operate] all over the country".[25]

South America

- The Biblioburro is a mobile library by which Colombian teacher Luis Soriano and his two donkeys, Alfa and Beto, bring books to children in rural villages twice a week. CNN chose Soriano as one of their 2010 Heroes of the Year.[35]

See also

References

- ↑ "Perambulating Library". The British Workman. February 1, 1857.

- ↑ "George Moore". Mealsgate.com. Retrieved September 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Orton, Ian (1980). An Illustrated History of Mobile Library Services in the UK with notes on traveling libraries and early public library transport. Sudbury: Branch and Mobile Libraries Group of the Library Association. ISBN 0-85365-640-1.

- ↑ "Library Timeline". Fairfax County.

- ↑ "History". Chester County Free Public Library. Retrieved May 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "The first county bookmobile in the US, Western Maryland Regional Library". whilbr.org.

- ↑ Joanne E. Passet (1994). "Itinerating Libraries". In Wayne A. Wiegand and Donald G. Davis. Encyclopedia of Library History. Taylor & Francis. pp. 315–317. ISBN 978-0-8240-5787-9.

- ↑ Washington County Free Library. First Annual Report for the Year ending October 1, 1902.

- ↑ Maryland State Archives. "Maryland Women's Hall of Fame". Washington County Free Library.

- ↑ Susan B. Roumfort (1997). "Sarah Byrd Askew, 1877-1942". In Joan N. Burstyn. Past and Promise: Lives of New Jersey Women. Syracuse University Press. pp. 103–104.

- ↑ "In the Beginning" (PDF). Hennepin County Library. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ WPA (July 2012). "Packhorse Librarians in Kentucky, 1936-1943" (PDF). University of Kentucky.

- ↑ Attig, Derek (April 12, 2012). "National Bookmobile Day: Aggregation Edition". HASTAC.

- ↑ "Mobile Libraries". Lincolnshire County Council. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

Wherever you live in Lincolnshire, whether in the countryside of the Wolds or Fens, the Coastal area or even on the edge of a town, a Mobile Library will stop nearby.

- ↑ Bashaw, D. (2010). "On the road again: A look at bookmobiles, then and now" (PDF). Children & Libraries. 8 (1). pp. 32–35.

- ↑ Jeffrey Schnapp; Matthew Battles (2014). Library Beyond the Book. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72503-4.

- ↑ "Bookmobile". The Internet Archive.

- ↑ "National Bookmobile Day". ALA.

- ↑ ALA. "Bookmobiles". Pinterest.

- ↑ "Kenya's children of the desert". Guardian Unlimited. December 2005. Retrieved June 2007. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Camel Library Service". Kenyan Camel Book Drive. Retrieved June 2007. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Hamilton, Masha (2007). The Camel Bookmobile. HarperCollins.

- ↑ "Donkeys help provide Multi-media Library Services". IFPlant. February 2002. Retrieved June 2007. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "The Indonesian horse that acts as a library". BBC NEWS. May 6, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Mobile Section" (PDF). IFLA Newsletter (1). Autumn 2002.

- ↑ "La biblioteca móvil". Madrid.org. Comunidad de Madrid [city government]. 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ↑ "Autobarrios San Cristobal: Acción / Espacio Público". Basurama.org. 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ↑ Milligan, Brian (Personal Finance Reporter (April 22, 2014). "Money on wheels: Banking gets seriously mobile". BBC News.

- ↑ "Books on Bikes Helps Seattle Librarians Pedal To The Masses".

- ↑ Johnson, Kirk (October 9, 2014). "Homeless Outreach in Volumes: Books by Bike for ‘Outside’ People in Oregon". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Volusia County Libraries Introduce Book Bike : NewsDaytonaBeach". newsdaytonabeach.com. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ↑ Attig, Derek (April 12, 2012). "Home page". bookmobility.

- ↑ Attig, Derek. "National Bookmobile Day: Aggregation Edition".

- ↑ American Libraries magazine. "Bookmobiles". Pinterest.

- ↑ "Luis Soriano". The Gallery of Heroes. CNN. November 2014.

Further reading

- Finnell, Joshua. "The Bookmobile: Defining the Information Poor". MSU Philosophy Club. An article on the history of the bookmobile in the US.

- King, Stephen (2011). "The Magic of the Bookmobile, Take Two". Read All Day.

- Kowalczyk, Piotr (January 9, 2015). "10 most extraordinary mobile libraries". Ebook Friendly.

- Moore, Benita (1989). A Lancashire Year. Preston: Carnegie Publishing. Based on experiences while working on the Lancashire County Library mobile library service in the 1960s.

- Nix, Larry T. (ed.). "A Tribute to the Bookmobile". Library History Buff. USA.

- Ortwein, Orty (ed.). "Bookmobiles: a History". Wordpress.

- Stringer, Ian (2001). Britain's Mobile Libraries. Appleby-in-Westmorland: Trans-Pennine Publishing in association with Branch & Mobile Libraries Group of the Library Association. ISBN 1-903016-15-0.

- Stringer, Ian (coordinated by) (2010). Mobile Library Guidelines. Paris: IFLA. ISBN 978-90-77897-45-4. ISSN 0168-1931.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bookmobiles. |

- American Library Association. "Bookmobiles". Pinterest.

- Association of Bookmobile & Outreach Services

- Boston Public Library (1963). "Bookmobile". Flickr.

- "Children's Mobile Libraries". Blogspot.