Mass for the Dresden court (Bach)

_WDL11619.pdf.jpg)

| Missa BWV 232 | |

|---|---|

| Missa (Kyrie and Gloria) by J. S. Bach | |

| Key | B minor |

| Related |

|

| Composed | 1733: Leipzig |

| Performed | possibly 1733: Dresden |

| Movements | 12 in 2 parts (3, 9) |

| Text | |

| Vocal | ssatb/SSATB |

| Instrumental | |

The Mass for the Dresden court is a Kyrie–Gloria Mass in B minor composed in 1733 by Johann Sebastian Bach. At the time Bach worked as a Lutheran church musician in Leipzig, but he composed the mass for the Catholic court in Dresden. The Mass (or in Latin: Missa) consists of a Kyrie in three movements and a Gloria in nine movements, and is an unusually extended work scored for SSATB soloists and choir, and an orchestra with a broad winds section.

It seems not very likely the work was ever performed during Bach's lifetime. After reusing some of its music in a cantata he composed around 1745 (BWV 191), Bach finally incorporated this Kyrie–Gloria Mass as first part of four in his Mass in B minor, composed/assembled in the last years of his life, around 1748–1749.

The Kyrie–Gloria Mass for the Dresden court was not assigned a separate number in the BWV catalogue, but in order to distinguish it from the later complete mass (BWV 232), numbers like BWV 232a and BWV 232I are in use.[1][2] In 2005 Bärenreiter published the 1733 version of the Missa as BWV 232 I, in the Neue Bach-Ausgabe series.[3] The work is also referred to as Missa 1733[4] or "The Missa of 1733".[5] The Bach-Digital website refers to the work as "BWV 232/I (Frühfassung)", i.e. "BWV 232/I (early version)".[6]

History

Bach was a Lutheran church musician, devoted to the composition of sacred music in German. He wrote more than 200 cantatas for the liturgy, most of them in Leipzig from 1723 to 1726 at the beginning of his tenure as Thomaskantor, responsible for the music at the major churches. In Leipzig, music on the traditional Latin texts were performed on holidays. Bach composed works on Latin texts, for example a Magnificat in 1723, performed both on the Marian feast Visitation and Christmas that year, and in 1724 a Sanctus for Christmas, which he later integrated into his Mass in B minor.[5][7] Both works were exceptional setting, the Magnificat extended and for five vocal parts, the Sanctus for six voices, while four-part singing was common in Leipzig.[8]

Bach's intentions with the composition

Augustus the Strong, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, died on 1 February 1733. He had converted to the Catholic Church in order to ascend the throne of Poland in 1697. During a period of mourning, no cantata performances were permitted. Bach composed a Missa, a setting of Kyrie and Gloria, for the court of Dresden,[9][10] where the successor was the later Augustus III of Poland. Bach presented the parts of the works to him with a note dated 27 July 1733, in the hope of obtaining the title, "Electoral Saxon Court Composer":

In deepest Devotion I present to your Royal Highness this small product of that science which I have attained in Musique, with the most humble request that you will deign to regard it not according to the imperfection of its Composition, but with a most gracious eye ... and thus take me into your most mighty Protection.[11]

A different translation of this polite understatement[12] is "an insignificant product of the skill I have attained in music."[13] In the note, Bach also complained that he had "innocently suffered one injury or another" in Leipzig.[14] Petitions to the new ruler after the death of the previous, as the one sent by Bach, were not exceptional in nature: similar petitions by musicians to August III included those of Jan Dismas Zelenka (unsuccessfully competing with Johann Adolph Hasse for the post of Kapellmeister),[15] Johann Joachim Quantz and Pantaleon Hebenstreit (a Lutheran court church director).[16] What was exceptional was that Bach accompanied his petition with a composition of considerable dimensions, and a liturgical composition no less, which seems strange while at the time Bach was a Lutheran church composer here presenting a work for a Catholic church service.

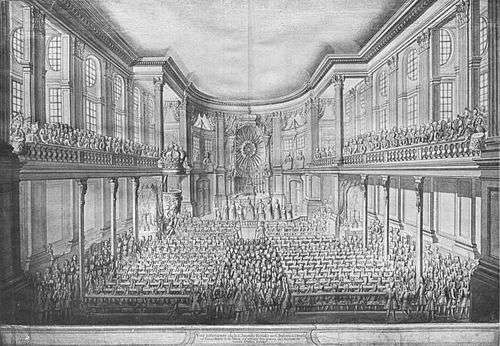

The location of the Sophienkirche is shown in the lower part of this plan excerpt.

At the time Germany lived under the cuius regio, eius religio principle (inhabitants of a region have to follow the religion of their ruler), which led to a somewhat double situation in Dresden under August the Strong: officially Catholic in Poland, but only privately so in Dresden — no Catholicism was imposed on Lutheran Saxony, only the court at Dresden was Catholic.[18] Lutherans, including the Electress Christiane Eberhardine who with determination refused to convert to Catholicism (and for whom Bach had composed his Trauerode when she died in 1727),[15] had the Sophienkirche as their place of worship,[lower-alpha 1] while the Catholic Hofkirche (Court church) was housed in the former court theatre from 1708.[19]

Luther hadn't rejected any of the five parts of the Mass ordinary that traditionally were eligible for a musical setting (Kyrie, Gloria, Nicene Creed, Sanctus, Agnus Dei): Protestant mass celebrations could include any of these and/or their translation in the local language.[20] There is no doubt Bach admired his ancestor Veit for his Lutheranism.[21] In all probability Bach wrote a Lutheran liturgical composition, that would have been as acceptable in a Catholic church service. At least the panache with which Bach showed off as a versatile composer, only six years after openly choosing the Lutheran side at the death of the new elector's mother, must be admired.

For the music, Bach borrowed extensively from his previous cantata compositions.[12] Bach may have had the capabilities of the instrumentalists of the Dresden court chapel (that served the Hofkirche) in mind when composing the piece: at the time these were among others Johann Georg Pisendel (violinist and concert master), Johann Christian Richter (hoboist), and the flautists Pierre-Gabriel Buffardin and Johann Joachim Quantz.[22] These performers, versed in as well the French as the Italian performance styles, were the best of what could be found anywhere in Europe.[15] The new elector's taste for the operatic genre was no secret either.[15] For church music the Neapolitan mass came closest to that genre, so this was the preferred Mass type at the Hofkirche.[2] Bach was no doubt aware that apart from the excellent instrumentalists, the Dresden Hofkapelle ("court chapel") also had vocal soloists at its disposition who could excel in the type of arias that was customary in operas and Neapolitan masses.[2][15]

The score Bach sent to Dresden consisted of the separate parts for Soprano I, Soprano II, Alto, Tenor, Bass, Trumpet I, Trumpet II, Trumpet III, Timpani, Corno da Caccia, Flauto traverso I, Flauto traverso II, Oboe (d'amore) I, Oboe (d'amore) II, Oboe (d'amore) III, Violins I (2 copies), Violins II, Viola, Cello, Bassoon and Basso continuo. Most of these copies were written by Bach himself, but for the last movements of both Kyrie and Gloria his sons Carl Philipp Emanuel (soprano parts), Wilhelm Friedemann (violino I parts), and his wife Anna Magdalena (cello parts) helped, along with an anonymous copyist (oboe and basso continuo parts).[23] Performance material for the chorus was not included, nor was the basso continuo part very elaborated.[24] All these parts appear to have been copied directly from the full score, which Bach kept in Leipzig.[5] Bach supplied the parts for single performers with many details that are not in the score he kept.[25]

Although some commentators suggest other liturgical and worldly venues where Bach may have anticipated a possible performance of the Missa,[27] there seems little doubt Bach intended to tailor the piece so that it could be performed at the Dresden Hofkirche.[2]

Reception at the Dresden court

When the composition arrived in Dresden its format wasn't very unusual compared to other works performed at the time at the Hofkirche. The repertoire performed there included over thirty masses consisting of only a Kyrie and Gloria. Many of these were composed or acquired by the thentime court composer Jan Dismas Zelenka, and in most cases, like it also happened to Bach's Missa, these were later expanded into a complete mass (missa tota), or at least a mass with all the usual mass sections except the Credo (missa senza Credo). Nor the fact that Bach's Missa was composed for virtuoso performers, nor that it was a composition requiring a SSATB choir could be considered exceptional at the time and place.[2]

The key signature of the mass was somewhat exceptional: the Hofkirche 1765 catalogue[28] contains only one Missa in B minor, by Antonio Caldara. D major, the relative major key of B minor (i.e. with the same accidentals), was the most usual key for festive music including trumpets, because of the Saxon natural trumpet: all of Zelenka's solemn masses were in that key, but also 6 of the 12 movements of Bach's Missa (including the Christe eleison and the opening and closing movements of the Gloria) have that same key signature. The most exceptional feature of Bach's mass appears to have been its duration, which largely exceeded what was usual compared to similar compositions at the time in Dresden. This seems the most likely reason why the composition was filed in the Royal Library upon arrival in Dresden, instead of being added to the repertoire of the Hofkirche.[2]

As for the result of his petition to the new ruler in Dresden: some three years after his request Bach received the title of Royal Court Composer.[2] In the intermediate period the Elector had other business to attend to: the War of the Polish Succession.

Performance history before being integrated in the Mass in B minor, BWV 232

It is debated if the Missa was performed at the time.[5] If it was performed, the most likely venue was the Sophienkirche in Dresden, where Bach's son Wilhelm Friedemann had been organist since June.[5][29]

Around 1745 Bach used three movements of the Gloria of this Missa for his cantata Gloria in excelsis Deo, BWV 191.[5][7]

Scoring and structure — incorporation in the Mass in B minor, BWV 232

In the last years of his life, presumably around 1748–1749, Bach integrated the complete Missa unchanged in his Mass in B minor, his only complete mass (or missa tota).[1] Scoring and structure are identical with the later work, but markings differ because the parts contain more details than the 1733 score which he kept. Bach made changes to that score when he completed the mass.[25]

The work is scored for five vocal parts, two sopranos, alto, tenor and bass, and an orchestra of three trumpets, timpani, corno da caccia, two flauti traversi, two oboes, two oboes d'amore, two bassoons, two violins, viola, and basso continuo.

The Kyrie is structured in three movements. Two different choral movements frame a duet for two sopranos. The Gloria is structured in nine movements in a symmetric arrangement around a duet of soprano and tenor.

The Missa forms a considerable part of the Mass in B minor which publisher Hans Georg Nägeli described in 1818 as "the greatest musical art work of all times and nations" when he tried a first publication.[13]

Publication

In 2005, Bärenreiter published the work, titled "Missa, BWV 232 I, Fassung von 1733", as part of the Neue Bach Ausgabe. The editor of three Early Versions of the Mass BWV 232, the others being "Credo in unum Deum, BWV 232 II, Frühfassung in G" and "Sanctus, BWV 232 III, Fassung von 1724" was Uwe Wolf.[3]

Notes

- ↑ Note that the Sophienkirche wasn't called Hofkirche before 1737, so for the purpose of this article, about a 1733 composition, "Hofkirche" exclusively refers to the Catholic court church housed in the former Opernhaus am Taschenberg and served by the court chapel musicians (also predating plans for the later Hofkirche/Cathedral built between the later Schloßplatz and Theaterplatz with about half a decade).

- ↑ Court chapel: in this instance referring to the church building, other instances of Hofkapelle/court chapel in this article generally refer to chapel as an ensemble of musicians, directed by a chapel master (Kapellmeister).

References

- 1 2 Laurson, Jens F. (2009). "Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) / Missa (1733)". musicweb-international.com. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stockigt 2013.

- 1 2 "Missa, BWV 232 I, Fassung von 1733, in "Bach, Johann Sebastian / Early Versions of the Mass BWV 232"". Bärenreiter. 2005. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ↑ Grob, Jochen. "Missa 1733" (in German). s-line.de. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Butt, John (1991). Bach: Mass in B Minor. Cambridge University Press. pp. 8–12. ISBN 0-521-38716-7.

- ↑ Bach Digital Work 0290 at www

.bach-digital .de - 1 2 Steinitz, Margaret. "Bach's Latin Church Music". London Bach Society. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ↑ Rathey, Markus (2003). "Johann Sebastian Bach's Mass in B Minor: The Greatest Artwork of All Times and All People" (PDF). bach.nau.edu. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ↑ "Missa b-minor (Kyrie and Gloria of the b-minor Mass)) BWV 232 (Frühfassung); BC E 2 / Mass". University of Leipzig. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ↑ Leisinger, Ulrich (2014). Foreword (PDF). Carus-Verlag. pp. IV–VI.

- ↑ Talbeck, Carol (2002). "Johann Sebastian Bach: Mass in B Minor / Everything must be possible. – J. S. Bach.". sfchoral.org. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- 1 2 Wolff 2013, p. 11.

- 1 2 "Missa in B Minor ("Kyrie" and "Gloria" of the B Minor Mass)". World Digital Library. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ↑ An English translation of the letter is given in Hans T. David and Arthur Mendel, The Bach Reader: A Life of Johann Sebastian Bach in Letters and Documents, W. W. Norton & Company, 1945, p. 128. (Also in "The New Bach Reader: A Life of Johann Sebastian Bach in Letters and Documents" revised by Christoph Wolff, W. W. Norton & Co Inc, 1998, ISBN 978-0-393-04558-1 , p. 158.)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dresden in the time of Zelenka and Hasse at earlymusicworld

.com , quoted from Goldberg Early Music Magazine. - ↑ Stockigt 2013, p. 40.

- ↑ "Musical chronicle of the city of Dresden." in Medien-Info by Dresden Marketing GmbH, 2013

- ↑ Leaver 2013, pp. 25-27.

- ↑ Leaver 2013, p. 27.

- ↑ Leaver 2013, pp. 24-25.

- ↑ Leaver 2013.

- ↑ Stockigt 2013, pp. 46-47.

- ↑ D-Dl Mus.2405-D-21 at Dresden, Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek (University library), available online at bach-digital

.de - ↑ Stockigt 2013, p. 53.

- 1 2 Leisinger, Ulrich (2014). "Care is an editor's highest priority" (in German). Carus-Verlag. pp. IV–VI.

- ↑ Hubert Ermisch. Das alte Archivgebäude am Taschenberge in Dresden: Ein Erinnerungsblatt. Dresden: Baensch, 1888.

- ↑ Stockigt 2013, p. 41.

- ↑ Janice B. Stockigt. "“CATALOGO (THEMATICO) [SIC] DELLA MUSICA DI CHIESA (CATHOLICA [SIC] IN DRESDA) COMPOSTA DA DIVERSI AUTORI – SECONDO L’ALFABETTO 1765”: AN INTRODUCTION"

- ↑ The details added in this section are from Christoph Wolff "Bach", III, 7 (§ 8), Grove Music Online ed., L. Macy. http://www.grovemusic.com/ . Last accessed August 9, 2007.

Sources

- Wolff, Christoph (2013). "Past, present and future perspectives on Bach's B-minor Mass". In Tomita, Yo; Leaver, Robin A.; Smaczny, Jan. Exploring Bach's B-minor Mass. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–20. ISBN 978-1-107-00790-1.

- Leaver, Robin A. (2013). "Bach's Mass: 'Catholic' or 'Lutheran'?". In Tomita, Yo; Leaver, Robin A.; Smaczny, Jan. Exploring Bach's B-minor Mass. Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–38. ISBN 978-1-107-00790-1.

- Stockigt, Janice B. (2013). "Bach's Missa BWV 232I in the context of Catholic Mass settings in Dresden, 1729–1733". In Tomita, Yo; Leaver, Robin A.; Smaczny, Jan. Exploring Bach's B-minor Mass. Cambridge University Press. pp. 39–53. ISBN 978-1-107-00790-1.

External links

- Mass in B minor, BWV 232: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Missa BWV 232: history, scoring, sources for text and music, translations to various languages, discography, discussion, bach-cantatas website