Half-pipe

A half-pipe is a structure used in gravity extreme sports such as snowboarding, skateboarding, skiing, freestyle BMX, and skating.

.jpg)

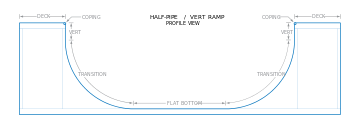

The structure resembles a cross section of a swimming pool, essentially two concave ramps (or quarter-pipes), topped by copings and decks, facing each other across a flat transition, also known as a tranny.[1] Originally half-pipes were half sections of a large diameter pipe. Since the 1980s, half-pipes contain an extended flat bottom between the quarter-pipes; the original style half-pipes are no longer built. Flat ground provides time to regain balance after landing and more time to prepare for the next trick.

Half-pipe applications include leisure recreation, skills development, competitive training, amateur and professional competition, demonstrations, and as an adjunct to other types of skills training. A skilled athlete can perform in a half-pipe for an extended period of time by pumping to attain extreme speeds with relatively little effort. Large (high amplitude) half-pipes make possible many of the aerial tricks in BMX, skating and skateboarding.

For winter sports such as freestyle skiing and snowboarding, a half-pipe can be dug out of the ground or snow perhaps combined with snow buildup. The plane of the transition is oriented downhill at a slight grade to allow riders to use gravity to develop speed and facilitate drainage of melt. In the absence of snow, dug out half-pipes can be used by dirtboarders, motorcyclists, and mountain bikers.

Performance in a half-pipe has been rapidly increasing over recent years. The current limit performed by a top-level athlete for a rotational trick in a half-pipe is 1440 degrees (four full 360 degree rotations). In top level competitions, rotation is generally limited to emphasize style and flow.

Origin

In the early 1970s, swimming pools were used by skateboarders in a manner similar to surfing ocean waves. In 1975, some teenagers from Encinitas, California, and other northern San Diego County communities began using 7.3-metre-diameter (24 ft) water pipes in the central Arizona desert associated with the Central Arizona Project, a federal public works project to divert water from the Colorado River to the city of Phoenix. Tom Stewart, one of these young California skateboarders,[2] looked for a more convenient location to have a similar skateboarding experience. Stewart consulted with his brother Mike, an architect, on how to build a ramp that resembled the Arizona pipes. With his brother's plans in hand, Tom built a wood frame half-pipe in the front yard of his house in Encinitas.

In a few days, the press had gotten word about Tom's creation and contacted him directly. Tom then went on to create Rampage, Inc. and began selling blueprints for his half-pipe design.[3] About five months later, Skateboarder magazine featured both Tom Stewart and Rampage. Little did Tom know that his design would go on to inspire countless others to follow in his foot steps.

Design

The character of a half-pipe depends on the relationship between four attributes: most importantly, the transition radius and the height, and less so, the degree of flat bottom and width. Extra width allows for longer slides and grinds. The flat bottom, while valued for recovery time, serves no purpose if it is longer than it needs to be.[4] Thus, it is the ratio between height and transition radius that determines the personality of a given ramp, because the ratio determines the angle of the lip.[5]

On half-pipes which are less than vertical, the height, typically between 50% and 75% of the radius, profoundly affects the ride up to and from the lip, and the speed at which tricks must be executed. Ramps near or below 0.91 m (3 ft) of height sometimes fall below 50% of the height of their radius. Technical skaters use them for advanced flip tricks and spin maneuvers. Smaller transitions that maintain the steepness of their larger counterparts are commonly found in pools made for skating and in custom mini ramps. The difficulty of technical tricks is increased with the steepness, but the feeling of dropping in from the coping is preserved.

Common mistake in the construction of ramps is constant radius in transitions: Most of the ramps are built with a quarter circle of constant radius for easy construction, but the best ramps are not constant radius but a parabola with little final vert (vertical).

The parabola allows for easy big air with return still on the curve and not on the flat.

Mathematics

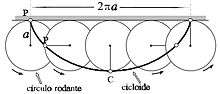

A cycloid profile will theoretically give the fastest half-pipe if friction is neglected. It is then called a brachistochrone curve. Such a curve in its pure form has infinitely short verts and is π times as wide as it is high.

Skateboarding, freestyle BMX, and aggressive inline skating

Frame and support for skateboard, BMX, and inline skating half-pipes frequently consist of a 2x6x8 lumber framework sheathed in plywood finished with sheets of masonite or Skatelite. Also, a metal frame finished in wood or metal is sometimes used.

Most commercial and contest ramps are surfaced by attaching sheets of some form of masonite to a frame. Many private ramps are surfaced in the same manner but may use plywood instead of masonite as surface material. Some ramps are constructed by spot-welding sheet metal to the frame, resulting in a fastener-free surface. Recent developments in technology have produced various versions of improved masonite substances such as Skatelite, RampArmor, and HARD-Nox.[6] These ramp surfaces are far more expensive than traditional materials.

Channels, extensions, and roll-ins are the basic ways to customize a ramp. Sometimes a section of the platform is cut away to form a roll-in and a channel to allow skaters to commence a ride without dropping in and perform tricks over the gap. Extensions are permanent or temporary additions to the height of one section of the ramp that can make riding more challenging.

Creating a spine ramp is another variation of the half-pipe. A spine ramp is basically two quarter pipes adjoined at the vertical edge.

Snow sports

Half-pipes in snow were originally done in large part by hand or with heavy machinery. Pipes were cut into snow using an apparatus similar to a grain elevator. The inventor was Colorado farmer Doug Waugh who created the Pipe Dragon used in both the 1998 and 2002 Winter Olympics.[7] The current method of half-pipe cutting is by use of a Zaugg Pipe Monster. Zaugg is based in Eggiwil, Switzerland. Zaugg Pipe Monsters have been used to build the Winter Olympic half-pipes, Winter X-Games, US Open Snowboarding Championship, the World Cup, and many, many more events around the world.[8] The Pipe Monster uses five cutting edges called haspels to cut the snow, rather than a chain. Also Zaugg pipe groomers create an elliptical shape that is safer and allows the rider to gain more speed. Zaugg has created a 6.7-metre (22 ft) Pipe Monster that for some years made the world's largest elliptical half-pipe. In winter sports, a 6.7 m (22 ft) halfpipe is called a superpipe.

There are two major companies training snowcat operators and building half-pipes for events such as the X Games. Planet Snow Design and Snow Park Technologies were founded on this growing snowboard market.

The current world record for highest jump in a half-pipe is held by freestyle skier, Peter Olenick. At Winter X Games XIV in Aspen, Colorado, Olenick achieved a height of 7.59 m (24 ft 11 in)

See also

References

- ↑ Human Kinetics (Organization); Hanlon, T.W. (2009). Sports Rules Book-3rd Edition, The. Human Kinetics. p. 206. ISBN 9781450408103. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ↑ Warren Bolster. "Warren Bolster "Master of Skateboard Photography" Image: Tom Stewart.". Concrete Wave Editions (February 2005). ISBN 0973528613.

- ↑ Warren Bolster. "Warren Bolster "Master of Skateboard Photography" Image: The Rampage.". Concrete Wave Editions (February 2005). ISBN 0973528613.

- ↑ "Vert ramp design". vert.co.za. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ↑ Lutzy. "RampCalc". Engineeringcalculator.net. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ↑ Skatelite Archived July 16, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The Dragon Lives On: Pipe Dragon inventor Doug Waugh passes away". Transworld Snowboarding. February 29, 2000. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Zaugg Pipe Monster". Zauggamerica.com. Retrieved April 3, 2014.