Minaret

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

| Dress |

| Holidays |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Theatre |

|

Minaret (/ˌmɪnəˈrɛt, ˈmɪnəˌrɛt/;[1] Persian: مناره menare, Turkish: minare,[2]), from Arabic: منارة manāra, lit. "lighthouse", also known as Goldaste (Persian: گلدسته), is a distinctive architectural structure akin to a tower and typically found adjacent to mosques. Generally a tall spire with a conical or onion-shaped crown, usually either free-standing or taller than associated support structure. The basic form of a minaret includes a base, shaft, and gallery.[3] Styles vary regionally and by period. Minarets provide a visual focal point and are traditionally used for the Muslim call to prayer.

Functions

The purpose of minarets in traditional Eastern region architecture is to serve as a ventilation system for a building in very hot climates. Usually, the building would consist of a tower with large open windows that would allow for cold air to enter, and a dome in the center of the building that would (hypothetically) have an opening in the ceiling that would both accumulate and allow warm air to leave the building through a cupola.[4] That buildings of middle eastern origins have such outstanding features is architecturally intentional. Mosques usually have a center hall room with a raised ceiling or dome to allow for heat to accumulate and rise upwards leaving the cold air on the lower floor allowing for a system of natural air conditioning.

However in modern times, with the invention of the modern air conditioners, the purpose of minarets has changed to traditional symbol. The minaret would be equipped with a speaker that would call people to prayers in Muslim countries. In addition to providing a visual cue to a Muslim community, the main function at present is to provide a vantage point from which the call to prayer, or adhan, is made. The call to prayer is issued five times each day: dawn, noon, mid-afternoon, sunset, and night. In most modern mosques, the adhān is called from the musallah (prayer hall) via microphone to a speaker system on the minaret.

History

The earliest mosques lacked minarets, and the call to prayer was performed elsewhere;[6] hadiths relay that the Muslim community of Medina gave the call to prayer from the roof of the house of Muhammad, which doubled as a place for prayer. Around 80 years after Muhammad's death, the first known minarets appeared.[7]

Minarets have been described as the "gate from heaven and earth", and as the Arabic language letter aleph (which is a straight vertical line).[8]

The massive minaret of the Great Mosque of Kairouan in Tunisia is the oldest standing minaret.[5][9] Its construction began during the first third of the 8th century and was completed in 836 CE.[10] The imposing square-plan tower consists of three sections of decreasing size reaching 31.5 meters.[10] Considered as the archetype for minarets of the western Islamic world, it served as a model for many later minarets.[10]

The tallest minaret, at 210 metres (689 ft) is located at the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca, Morocco. In some of the oldest mosques, such as the Great Mosque of Damascus, minarets originally served as illuminated watchtowers (hence the derivation of the word from the Arabic nur, meaning "light").

Construction

The basic form of minarets consists of three parts: a base, shaft, and a gallery. For the base, the ground is excavated until a hard foundation is reached. Gravel and other supporting materials may be used as a foundation; it is unusual for the minaret to be built directly upon ground-level soil. Minarets may be conical (tapering), square, cylindrical, or polygonal (faceted). Stairs circle the shaft in a counter-clockwise fashion, providing necessary structural support to the highly elongated shaft. The gallery is a balcony that encircles the upper sections from which the muezzin may give the call to prayer. It is covered by a roof-like canopy and adorned with ornamentation, such as decorative brick and tile work, cornices, arches and inscriptions, with the transition from the shaft to the gallery typically sporting muqarnas.

Local styles

Styles and architecture can vary widely according to region and time period. Here are a few styles and the localities from which they derive:

_(14594614317).jpg)

- Tunisia

- (7th century) Quadrangular, the Mosque of Uqba of Kairouan has the oldest minaret in the Muslim world.

- Turkish (11th century)

- 1, 2, 4 or 6 minarets related to the size of the mosque. Slim, circular minarets of equal cross-section are common.

- Egypt (7th century) / Syria (until 13th century)

- Low square towers sitting at the four corners of the mosque.

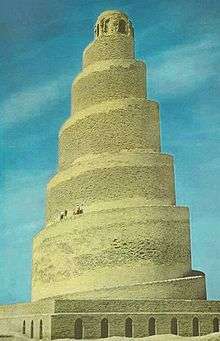

- Iraq

- For a free-standing conical minaret surrounded by a spiral staircase, see Malwiya.

- Egypt (15th century)

- Octagonal. Two balconies, the upper smaller than the lower, projecting mukarnas, surmounted by an elongated finial.

- Persia (Iran) (17th century)

- Generally two pairs of slim, blue tile-clad towers flanking the mosque entrance, terminating in covered balconies.

- Tatar (18th century)

- Tatar mosque: A sole minaret, located at the centre of a gabled roof.

- Morocco

- Typically, a single square minaret; notable exceptions include a few octagonal minarets in northern cities - Chefchaouen, Tetouan, Rabat, Ouezzane, Asilah, and Tangier - and the round minaret of Moulay Idriss.

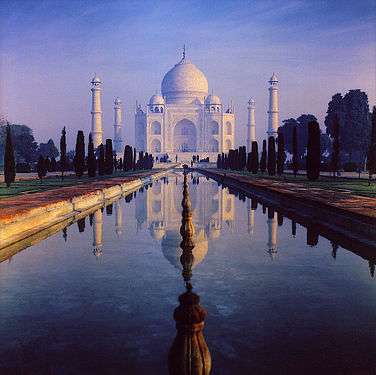

- South Asia

- Octagonal, generally three balconied, with the upper most roofed by an onion dome and topped by a small finial.

Examples

- Square three-tiered minaret (the oldest in existence) of the Mosque of Uqba (Great Mosque of Kairouan), Tunisia

.jpg) Qutub Minar in Delhi

Qutub Minar in Delhi Minaret in Eger, Hungary, the most northern left from Ottoman rule

Minaret in Eger, Hungary, the most northern left from Ottoman rule Baitul Futuh Mosque minaret in London, United Kingdom

Baitul Futuh Mosque minaret in London, United Kingdom- Islamic architecture in a mosque with two minarets in Nishapur

Minaret in Wangen bei Olten, Switzerland

Minaret in Wangen bei Olten, Switzerland Minaret of the Great Mosque of Granada, Spain

Minaret of the Great Mosque of Granada, Spain Faisal Mosque's minarets, Islamabad, Pakistan

Faisal Mosque's minarets, Islamabad, Pakistan The Charminar in Hyderabad, India

The Charminar in Hyderabad, India- The minaret of Baitul Mukarram in Dhaka, Bangladesh

The minaret of the Al-Muhdhar Mosque in Tarim, Yemen

The minaret of the Al-Muhdhar Mosque in Tarim, Yemen Ancient Indian-style minaret of Menara Kudus Mosque in Java, Indonesia

Ancient Indian-style minaret of Menara Kudus Mosque in Java, Indonesia Minaret of Medan's Grand Mosque, Indonesia

Minaret of Medan's Grand Mosque, Indonesia Minaret of Central Java Grand Mosque, Indonesia

Minaret of Central Java Grand Mosque, Indonesia- Twin minarets of Bandung Grand Mosque, Indonesia

- Modern style minaret of Istiqlal Mosque, Jakarta in Indonesia

Minaret of National Mosque of Malaysia

Minaret of National Mosque of Malaysia Minaret of Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin Mosque, Brunei

Minaret of Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin Mosque, Brunei.jpg) The minaret of the Wazir Khan Mosque in Lahore, Pakistan

The minaret of the Wazir Khan Mosque in Lahore, Pakistan One of the minarets of the Badshahi Mosque also in Lahore, Pakistan

One of the minarets of the Badshahi Mosque also in Lahore, Pakistan Old adobe minaret in Kharanagh, Iran

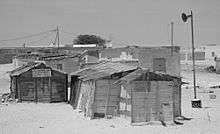

Old adobe minaret in Kharanagh, Iran Simple wooden pole used as minaret in Nouadhibou, Mauritania

Simple wooden pole used as minaret in Nouadhibou, Mauritania

- Chinese-style minaret of Tongxin Great Mosque, Ningxia, China

Sabah State Mosque minaret in Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia (Borneo)

Sabah State Mosque minaret in Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia (Borneo)- Minaret at mosque in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

The minaret in the Prophet's Mosque in Madinah, Saudi Arabia

The minaret in the Prophet's Mosque in Madinah, Saudi Arabia The "bare tower" of Huaisheng Mosque, Guangzhou, China

The "bare tower" of Huaisheng Mosque, Guangzhou, China A Burmese-style mosque with an elaborately carved minaret in Amarapura

A Burmese-style mosque with an elaborately carved minaret in Amarapura- Minaret in Kashgar, China

Chinguetti mosque minaret, in Mauritania

Chinguetti mosque minaret, in Mauritania El-Tabia Mosque with two minarets in Aswan, Egypt

El-Tabia Mosque with two minarets in Aswan, Egypt- The four minarets in Mashkhur Jusup Central Mosque, Pavlodar, Kazakhstan

A minaret of a mosque in central Jubail, Saudi Arabia

A minaret of a mosque in central Jubail, Saudi Arabia Minaret of Al Othman Mosque in Jebla, Kuwait; built in 1857.

Minaret of Al Othman Mosque in Jebla, Kuwait; built in 1857.- The Ghawanima Minaret, 1900; one of the four minarets of Al-Aqsa Mosque, Old City Jerusalem

The Centro Islámico de Puerto Rico in Ponce, Puerto Rico

The Centro Islámico de Puerto Rico in Ponce, Puerto Rico- The octagonal minaret of Hammouda Pacha Mosque in Tunis, built in the 17th century

- The onion dome of Mecca Masjid minaret, Hyderabad, India.

Hagia Sophia in Istanbul (Constantinople). The minarets were added during its conversion from cathedral to mosque, after the conquest of Constantinople

Hagia Sophia in Istanbul (Constantinople). The minarets were added during its conversion from cathedral to mosque, after the conquest of Constantinople

See also

References

- ↑ "minaret". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ "minaret." Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. 21 Mar. 2009.

- ↑ Dynamic response of masonry minarets strengthened with Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) composites (Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences) p. 2012

- ↑ Research Gate. The 7th International Conference - Healthy Buildings 2003, At Singapore https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272293471_Ventilation_in_a_Mosque_-_an_Additional_Purpose_the_Minarets_May_Serve. Retrieved 31 August 2016. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 Titus Burckhardt, Art of Islam, Language and Meaning: Commemorative Edition. World Wisdom. 2009. p. 128

- ↑ Donald Hawley, Oman, pg. 201. Jubilee edition. Kensington: Stacey International, 1995. ISBN 0905743636

- ↑ Paul Johnson, Civilizations of the Holy Land. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1979, p. 173

- ↑ University of London, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Volume 68. The School. 2005. p. 26

- ↑ Linda Kay Davidson and David Martin Gitlitz, Pilgrimage: from the Ganges to Graceland: an encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. 2002. p. 302

- 1 2 3 Minaret of the Great Mosque of Kairouan (Qantara Mediterranean Heritage)

Further reading

- Jonathan M. Bloom (1989), Minaret, symbol of Islam, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-728013-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Minarets. |

-Jerusalem-Temple_Mount-Dome_of_the_Rock_(SE_exposure).jpg)