Min Chinese

| Min | |

|---|---|

| 閩語/闽语 | |

| Ethnicity | Han Chinese |

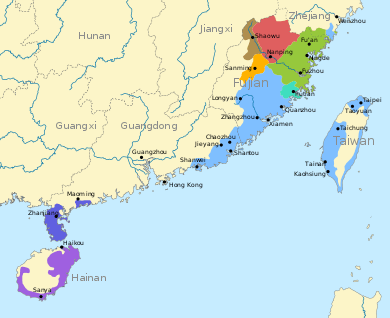

| Geographic distribution | China: Fujian, Guangdong (around Chaozhou-Swatou and Leizhou peninsula), Hainan, Zhejiang (Shengsi, Putuo and Wenzhou), Jiangsu (Liyang and Jiangyin); Taiwan; overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia and North America |

| Linguistic classification | |

Early forms | |

| Proto-language | Proto-Min |

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-6 | mclr |

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-h to 79-AAA-l |

| Glottolog | minn1248 |

|

Distribution of Min languages in Taiwan and China. | |

| Min Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Bân gú / Mìng ngṳ̄ ('Min') written in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 閩語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 闽语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hokkien POJ | Bân gú | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Min or Miin[lower-alpha 1] (simplified Chinese: 闽语; traditional Chinese: 閩語; pinyin: Mǐn yǔ; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Bân gú; BUC: Mìng ngṳ̄) is a broad group of Chinese varieties spoken by over 70 million people in the southeastern Chinese province of Fujian as well as by migrants from this province in Guangdong (around Chaozhou-Swatou, or Chaoshan area, Leizhou peninsula and Part of Zhongshan), Hainan, three counties in southern Zhejiang, Zhoushan archipelago off Ningbo, some towns in Liyang, Jiangyin City in Jiangsu province, and Taiwan. The name is derived from the Min River in Fujian. Min varieties are not mutually intelligible with any other varieties of Chinese.

There are many Min speakers among overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia. The most widely spoken variety of Min outside Fujian is Hokkien (which includes Taiwanese and Amoy).

History

The Min homeland of Fujian was opened to Chinese settlement by the defeat of the Minyue state by the armies of Emperor Wu of Han in 110 BC.[1] The area features rugged mountainous terrain, with short rivers that flow into the South China Sea. Most subsequent migration from north to south China passed through the valleys of the Xiang and Gan rivers to the west, so that Min varieties have experienced less northern influence than other southern groups.[2] As a result, whereas most varieties of Chinese can be treated as derived from Middle Chinese, the language described by rhyme dictionaries such as the Qieyun (601 AD), Min varieties contain traces of older distinctions.[3] Linguists estimate that the oldest layers of Min dialects diverged from the rest of Chinese around the time of the Han dynasty.[4][5] However, significant waves of migration from the North China Plain occurred:[6]

- The Uprising of the Five Barbarians during the Jin dynasty, particularly the Disaster of Yongjia in 311 AD, caused a tide of immigration to the south.

- In 669, Chen Zheng and his son Chen Yuanguang from Gushi County in Henan set up a regional administration in Fujian to suppress an insurrection by the She people.

- Wang Chao was appointed governor of Fujian in 893, near the end of the Tang dynasty, and brought tens of thousands of troops from Henan. In 909, following the fall of the Tang dynasty, his son Wang Shenzhi founded the Min Kingdom, one of the Ten Kingdoms in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

Jerry Norman identifies four main layers in the vocabulary of modern Min varieties:

- A non-Chinese substratum from the original languages of Minyue, which Norman and Mei Tsu-lin believe were Austroasiatic.[7][8]

- The earliest Chinese layer, brought to Fujian by settlers from Zhejiang to the north during the Han dynasty.[9]

- A layer from the Northern and Southern dynasties period, which is largely consistent with the phonology of the Qieyun dictionary.[10]

- A literary layer based on the koiné of Chang'an, the capital of the Tang dynasty.[11]

Geographic location and subgrouping

Min is usually described as one of seven or ten groups of varieties of Chinese but has greater dialectal diversity than any of the other groups. The varieties used in neighbouring counties, and in the mountains of western Fujian even in adjacent villages, are often mutually unintelligible.[12]

Early classifications, such as those of Li Fang-Kuei in 1937 and Yuan Jiahua in 1960, divided Min into Northern and Southern subgroups.[13][14] However, in a 1963 report on a survey of Fujian, Pan Maoding and colleagues argued that the primary split was between inland and coastal groups. A key discriminator between the two groups is a group of words that have a lateral initial /l/ in coastal varieties, and a voiceless fricative /s/ or /ʃ/ in inland varieties, contrasting with another group having /l/ in both areas. Norman reconstructs these initials in Proto-Min as voiceless and voiced laterals that merged in coastal varieties.[14][15]

Coastal Min

The coastal varieties have the vast majority of speakers, and have spread from their homeland in Fujian and eastern Guangdong to the islands of Taiwan and Hainan, to other coastal areas of southern China and to Southeast Asia.[16] Pan and colleagues divided them into three groups:[17]

- Eastern Min (Min Dong), centered around the city of Fuzhou, the capital of Fujian province, with Fuzhou dialect as the prestige form.

- Pu-Xian Min is spoken in the city of Putian and the county of Xianyou County. Li Rulong and Chen Zhangtai examined 214 words, finding 62% shared with Quanzhou dialect (Southern Min) and 39% shared with Fuzhou dialect (Eastern Min), and concluded that Pu-Xian was more closely related to Southern Min.[18]

- Southern Min (Min Nan) originates from the south of Fujian and the eastern corner of Guangdong. In common parlance, Southern Min usually refers to Hokkien, of which the two major poles are the Amoy dialect of Xiamen and Taiwanese Hokkien of Taiwan. Zhenan Min of Cangnan County in southern Zhejiang is also of this type. Related Hokkien varieties are spoken in Chinese communities spread across Southeast Asia.[19] The Teochew and Shantou dialects of the Chaoshan region of eastern Guangdong have difficult mutual intelligibility with the Amoy dialect. Chaoshan varieties are also spoken by most Thai Chinese.[14]

The Language Atlas of China (1987) includes distinguished two further groups, which had previously been included in Southern Min:[20]

- Leizhou Min, spoken on the Leizhou Peninsula in southwestern Guangdong.

- Hainanese, spoken on the island of Hainan. These dialects feature drastic changes to initial consonants, including a series of implosive consonants, that have been attributed to contact with the Tai–Kadai languages spoken on the island.[21]

Coastal varieties feature some uniquely Min vocabulary, including pronouns and negatives.[22] All but the Hainan dialects have complex tone sandhi systems.[23]

Inland Min

Although they have far fewer speakers, the inland varieties show much greater variation than the coastal ones.[24] Pan and colleagues divided the inland varieties into two groups:[17]

- Northern Min (Min Bei) is spoken in Nanping prefecture in Fujian, with Jian'ou dialect taken as typical.

- Central Min (Min Zhong), spoken in Sanming prefecture.

The Language Atlas of China (1987) included a further group:[20]

- Shao-Jiang Min, spoken in the northwestern Fujian counties of Shaowu and Jiangle, were classified as Hakka by Pan and his associates.[14] However, Jerry Norman suggested that they were inland varieties of Min that had been subject to heavy Gan or Hakka influence.[25]

Although coastal varieties can be derived from a proto-language with four series of stops or affricates at each point of articulation (e.g. /t/, /tʰ/, /d/, and /dʱ/), inland varieties contain traces of two further series, which Norman termed "softened stops" due to their reflexes in some varieties.[26][27][28] Inland varieties use pronouns and negatives cognate with those in Hakka and Yue.[22] Inland varieties have little or no tone sandhi.[23]

Vocabulary

Most Min vocabulary corresponds directly to cognates in other Chinese varieties, but there is also a significant number of distinctively Min words that may be traced back to proto-Min. In some cases a semantic shift has occurred in Min or the rest of Chinese:

- *tiaŋB 鼎 "wok". The Min form preserves the original meaning "cooking pot", but in other Chinese varieties this word (MC tengX > dǐng) has become specialized to refer to ancient ceremonial tripods.[29]

- *dzhənA "rice field". In Min this form has displaced the common Chinese term tián 田.[30][31] Many scholars identify the Min word with chéng 塍 (MC zying) "raised path between fields", but Norman argues that it is cognate with céng 層 (MC dzong) "additional layer or floor", reflecting the terraced fields commonly found in Fujian.[32]

- *tšhioC 厝 "house".[33] Norman argues that the Min word is cognate with shù 戍 (MC syuH) "to guard".[34][35]

- *tshyiC 喙 "mouth". In Min this form has displaced the common Chinese term kǒu 口.[36] It is believed to be cognate with huì 喙 (MC xjwojH) "beak, bill, snout; to pant".[35]

Norman and Mei Tsu-lin have suggested an Austroasiatic origin for some Min words:

- *-dəŋA "shaman" may be compared with Vietnamese đồng (/ɗoŋ2/) "to shamanize, to communicate with spirits" and Mon doŋ "to dance (as if) under demonic possession".[37][38]

- *kiɑnB 囝 "son" appears to be related to Vietnamese con (/kɔn/) and Mon kon "child".[39][40]

In other cases, the origin of the Min word is obscure. Such words include *khauA 骹 "foot",[41] *-tsiɑmB 䭕 "insipid"[42] and *dzyŋC 𧚔 "to wear".[34]

Writing system

When using Chinese characters to write a non-Mandarin form, standard practice is to use characters that correspond etymologically to the words being represented, and to invent new characters for words with no evident ancient Chinese etymology or in some cases for alternative pronunciations of existing characters, especially when the meaning is significantly different. Written Cantonese has carried this process out to the farthest extent of any non-Mandarin variety, to the extent that pure Cantonese vernacular can be unambiguously written using Chinese characters. Contrary to popular belief, a vernacular written in this fashion is not in general comprehensible to a Mandarin speaker, due to significant changes in grammar and vocabulary and the necessary use of large number of non-Mandarin characters.

A similar process has never taken place for any of the Min varieties and there is no standard system for writing Min, although some specialized characters have been created. Given that Min combines the Chinese of several different periods and contains some non-Chinese vocabulary, one may have trouble finding the appropriate Chinese characters for some Min vocabulary. In the case of Taiwanese, there are also indigenous words borrowed from Formosan languages, as well as a substantial number of loan words from Japanese. The Min spoken in Singapore and Malaysia has borrowed heavily from Malay and, to a lesser extent, from English and other languages. The result is that cases of Min written purely in Chinese characters does not represent actual Min speech, but contains a heavy mixture of Mandarin forms.

Attempts to faithfully represent Min speech necessarily rely on romanization, i.e. representation using Latin characters. Some Min speakers use the Church Romanization (Chinese: 教會羅馬字; pinyin: Jiaohui Luomazi). For Hokkien the romanization is called Pe̍h-ōe-jī (POJ) and for Fuzhou dialect called Foochow Romanized (Bàng-uâ-cê, BUC). Both systems were created by foreign missionaries in the 19th century (see Min Nan and Min Dong Wikipedia). There are some uncommon publications in mixed writing, using mostly Chinese characters but using the Latin alphabet to represent words that cannot easily be represented by Chinese characters.

Notes

References

- ↑ Norman (1991), pp. 328.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 210, 228.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 228–229.

- ↑ Ting (1983), pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 33, 79.

- ↑ Yan (2006), p. 120.

- ↑ Norman & Mei (1976).

- ↑ Norman (1991), pp. 331–332.

- ↑ Norman (1991), pp. 334–336.

- ↑ Norman (1991), p. 336.

- ↑ Norman (1991), p. 337.

- ↑ Norman (1988), p. 188.

- ↑ Kurpaska (2010), p. 49.

- 1 2 3 4 Norman (1988), p. 233.

- ↑ Branner (2000), pp. 98–100.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 232–233.

- 1 2 Kurpaska (2010), p. 52.

- ↑ Li & Chen (1991).

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 232–3.

- 1 2 Kurpaska (2010), p. 71.

- ↑ Lien (2015), p. 169.

- 1 2 Norman (1988), pp. 233–234.

- 1 2 Norman (1988), p. 239.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 235, 241.

- ↑ Norman (1973).

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 228–230.

- ↑ Branner (2000), pp. 100–104.

- ↑ Norman (1988), p. 231.

- ↑ Norman (1981), p. 58.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Norman (1981), p. 47.

- 1 2 Norman (1988), p. 232.

- 1 2 Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 33.

- ↑ Norman (1981), p. 41.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Norman & Mei (1976), pp. 296–297.

- ↑ Norman (1981), p. 63.

- ↑ Norman & Mei (1976), pp. 297–298.

- ↑ Norman (1981), p. 44.

- ↑ Norman (1981), p. 56.

Sources

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (2014), Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5.

- Bodman, Nicholas C. (1985), "The Reflexes of Initial Nasals in Proto-Southern Min-Hingua", in Acson, Veneeta; Leed, Richard L., For Gordon H. Fairbanks, Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications, 20, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 2–20, ISBN 978-0-8248-0992-8, JSTOR 20006706.

- Branner, David Prager (2000), Problems in Comparative Chinese Dialectology — the Classification of Miin and Hakka, Trends in Linguistics series, 123, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-015831-1.

- Chang, Kuang-yu (1986), Comparative Min phonology (Ph.D.), University of California, Berkeley.

- Kurpaska, Maria (2010), Chinese Language(s): A Look Through the Prism of "The Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects", Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-021914-2.

- Li, Rulong 李如龙; Chen, Zhangtai 陈章太 (1991), "Lùn Mǐn fāngyán nèibù de zhǔyào chāyì 论闽方言内部的主要差异" [On the main differences between Min dialects], in Chen, Zhangtai; Li, Rulong, Mǐnyǔ yánjiū 闽语硏究 [Studies on the Min dialects], Beijing: Yuwen Chubanshe, pp. 58–138, ISBN 978-7-80006-309-1.

- Lien, Chinfa (2015), "Min languages", in Wang, William S.-Y.; Sun, Chaofen, The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics, Oxford University Press, pp. 160–172, ISBN 978-0-19-985633-6.

- Norman, Jerry (1973), "Tonal development in Min", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 1 (2): 222–238, JSTOR 23749795.

- —— (1988), Chinese, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- —— (1991), "The Mǐn dialects in historical perspective", in Wang, William S.-Y., Languages and Dialects of China, Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monograph Series, 3, Chinese University Press, pp. 325–360, JSTOR 23827042, OCLC 600555701.

- —— (2003), "The Chinese dialects: phonology", in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (eds.), The Sino-Tibetan languages, Routledge, pp. 72–83, ISBN 978-0-7007-1129-1.

- Norman, Jerry; Mei, Tsu-lin (1976), "The Austroasiatics in Ancient South China: Some Lexical Evidence" (PDF), Monumenta Serica, 32: 274–301, JSTOR 40726203.

- Ting, Pang-Hsin (1983), "Derivation time of colloquial Min from Archaic Chinese", Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, 54 (4): 1–14.

- Yan, Margaret Mian (2006), Introduction to Chinese Dialectology, LINCOM Europa, ISBN 978-3-89586-629-6.

- Yue, Anne O. (2003), "Chinese dialects: grammar", in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (eds.), The Sino-Tibetan languages, Routledge, pp. 84–125, ISBN 978-0-7007-1129-1.