Military leadership in the American Civil War

Military leadership in the American Civil War was influenced by professional military education and the hard-earned pragmatism of command experience. While not all leaders had formal military training, the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York and the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis created dedicated cadres of professional officers whose understanding of military science had profound effect on the conduct of the American Civil War and whose lasting legacy helped forge the traditions of the modern U.S. officer corps of all service branches.

The Union

Civilian military leaders

President Abraham Lincoln was Commander-in-Chief of the Union armed forces throughout the conflict; after his April 14, 1865 assassination, Vice President Andrew Johnson became the nation's chief executive.[1] Lincoln's first Secretary of War was Simon Cameron; Edwin M. Stanton was confirmed to replace Cameron in January 1862. Thomas A. Scott was Assistant Secretary of War. Gideon Welles was Secretary of the Navy, aided by Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Fox.[2]

Regular Army officers

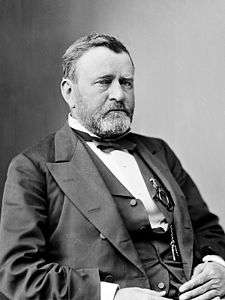

When the war began, the American standing army or "Regular army" consisted of only 1080 commissioned officers and 15,000 enlisted men.[3] Although 142 regular officers became Union generals during the war, most remained "frozen" in their regular units. That stated, most of the major Union wartime commanders had significant previous regular army experience.[4] Over the course of the war, the Commanding General of the United States Army was, in order of service, Winfield Scott, George B. McClellan, Henry Halleck, and finally, Ulysses S. Grant.

- Robert Anderson

- Don Carlos Buell

- John Buford

- Ambrose Burnside

- Edward Canby

- Philip St. George Cooke

- Jacob Dolson Cox

- Thomas Turpin Crittenden

- Thomas Leonidas Crittenden

- Samuel Curtis

- Abner Doubleday

- James A. Garfield

- Quincy Adams Gillmore

- Ulysses S. Grant

- Henry Wager Halleck

- Winfield Scott Hancock

- Joseph Hooker

- Andrew A. Humphreys

- Henry Jackson Hunt

- George B. McClellan

- Irvin McDowell

- James B. McPherson

- Joseph K. Mansfield

- George Meade

- Montgomery C. Meigs

- Dixon S. Miles

- Edward Ord

- John Pope

- John F. Reynolds

- William Rosecrans

- John Schofield

- Winfield Scott

- John Sedgwick

- Philip Sheridan

- William T. Sherman

- Andrew Jackson Smith

- William Farrar Smith

- George Stoneman

- George Henry Thomas

- Alfred Thomas Archimedes Torbert

- Gouverneur K. Warren

- John E. Wool

Militia and political leaders appointed to Union military leadership

Under the United States Constitution, each state recruited, trained, equipped, and maintained local militia; regimental officers were appointed and promoted by state governors. After states answered Lincoln's April 15, 1861, ninety-day call for 75,000 volunteer soldiers, most Union states' regiments and batteries became known as "Volunteers" to distinguish between state and regular army units. Union brigade-level officers (generals) could receive two different types of Federal commissions: U.S. Army or U.S. Volunteers (ex: Major General, U.S.A. as opposed to Major General, U.S.V.). While most Civil War generals held volunteer or brevet rank, many generals held both types of commission; regular rank was considered superior.[5]

- Edward D. Baker

- Nathaniel Prentice Banks

- Francis Preston Blair, Jr.

- Benjamin Franklin Butler

- Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain

- John Adams Dix

- John C. Frémont

- John Alexander McClernand

- Daniel Sickles

Native American and international officers in Union Army

Reflecting the multi-national makeup of the soldiers engaged, some Union military leaders derived from nations other than the United States.

- Philippe, Comte de Paris

- Michael Corcoran

- Włodzimierz Krzyżanowski

- Thomas Francis Meagher

- Ely Parker

- Albin F. Schoepf

- Carl Schurz

- Franz Sigel

- Régis de Trobriand

- Ivan Turchaninov

Union naval leaders

The rapid rise of the United States Navy during the Civil War contributed enormously to the North's ability to effectively blockade ports and Confederate shipping from quite early in the conflict. Handicapped by an aging 90 ship fleet, and despite significant manpower losses to the Confederate Navy after secession, a massive ship construction campaign embracing technological innovations from civil engineer James Buchanan Eads and naval engineers like Benjamin F. Isherwood and John Ericsson, along with four years' daily experience with modern naval conflict put the U. S. Navy onto a path which has led to today's world naval dominance.[6]

- John A. Dahlgren

- Charles Henry Davis

- Samuel Francis du Pont

- David Farragut

- Andrew Hull Foote

- Samuel Phillips Lee

- David Dixon Porter

- John Ancrum Winslow

- John Lorimer Worden

The Confederacy

Jefferson Davis  Robert E. Lee  T.J. "Stonewall" Jackson  James Longstreet  Joseph E. Johnston  James Waddell |

Civilian military leaders

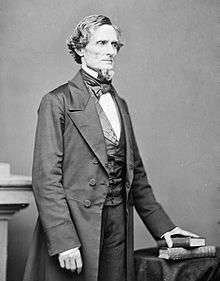

Jefferson Davis was named provisional president on February 9, 1861, and assumed similar commander-in-chief responsibilities as would Lincoln; on November 6, 1861 Davis was elected President of the Confederate States of America under the Confederate Constitution. Alexander H. Stephens was appointed as Vice President of the Confederate States of America on February 18, 1861, and later assumed identical vice presidential responsibilities as Hannibal Hamlin did. Several men served the Confederacy as Secretary of War, including Leroy Pope Walker, Judah P. Benjamin, George W. Randolph, James Seddon, and John C. Breckinridge. Stephen Mallory was Confederate Secretary of the Navy throughout the conflict.[7]

Former Regular Army officers

In the wake of secession, many regular officers felt they could not betray loyalty to their home state, as a result some 313 of those officers resigned their commission and in many cases took up arms for the Confederate Army. Himself a graduate of West Point and a former regular officer, Confederate President Jefferson Davis highly prized these valuable recruits to the cause and saw that former regular officers were given positions of authority and responsibility.[8]

- Richard H. Anderson

- P.G.T. Beauregard

- Milledge Luke Bonham

- Braxton Bragg

- Simon Bolivar Buckner, Sr.

- George B. Crittenden

- Samuel Cooper

- Jubal Anderson Early

- Richard S. Ewell

- Franklin Gardner

- Robert S. Garnett

- Josiah Gorgas

- William Joseph Hardee

- Ambrose Powell Hill

- Daniel Harvey Hill

- John Bell Hood

- Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson

- Albert Sidney Johnston

- Joseph E. Johnston

- Robert E. Lee

- Stephen D. Lee

- Mansfield Lovell

- James Longstreet

- John B. Magruder

- Humphrey Marshall

- Dabney Herndon Maury

- John Hunt Morgan

- John C. Pemberton

- George Pickett

- Edmund Kirby Smith

- Gustavus Woodson Smith

- J.E.B. Stuart

- William B. Taliaferro

- Earl Van Dorn

- Joseph Wheeler

- Henry A. Wise

Militia and political leaders appointed to Confederate military leadership

The land of Davy Crockett and Andrew Jackson, the state military tradition was especially strong in southern states, some of which were until recently frontier areas. Several significant Confederate military leaders emerged from state unit commands.

- John C. Breckinridge

- Benjamin F. Cheatham

- Nathan Bedford Forrest

- Wade Hampton

- James L. Kemper

- Ben McCulloch

- Leonidas Polk

- Sterling Price

- Richard Taylor

Native American and international officers in Confederate army

While no foreign power sent troops or commanders directly to assist the Confederate States, some leaders derived from countries other than the United States.

- Patrick Cleburne

- Stand Watie

- Camille Armand Jules Marie, Prince de Polignac

- Raleigh E. Colston

- Collett Leventhorpe

- George St. Leger Grenfell

Confederate naval leaders

The Confederate Navy possessed no extensive shipbuilding facilities; instead, it relied on refitting captured ships or purchased warships from Great Britain. The South had abundant navigable inland waterways, but after the Union built a vast fleet of gunboats, they soon dominated the Mississippi, Tennessee, Cumberland, Red and other rivers, rendering those waterways almost useless to the Confederacy. Confederates did seize several Union Navy vessels in harbor after secession and converted a few into ironclads, like the CSS Virginia. Blockade runners were built and operated by British naval interests, although by late in the war the C.S. Navy operated some. A few new vessels were built or purchased in Britain, notably the CSS Shenandoah and the CSS Alabama. These warships acted as raiders, wreaking havoc with commercial shipping. Aggrieved by these losses, in 1871 the U.S. government was awarded damages from Great Britain in the Alabama Claims.[6]

- John Mercer Brooke

- Isaac Newton Brown

- Franklin Buchanan

- James Dunwoody Bulloch

- Catesby ap Roger Jones

- Matthew Fontaine Maury

- Raphael Semmes

- Josiah Tattnall

- James Iredell Waddell

See also

- Civil War Generals

- History of Confederate States Army Generals

- Confederate States Armed Forces

- Union Army

- Union Navy

Notes

References

- Boatner, Mark Mayo, III. The Civil War Dictionary. New York: McKay, 1959; revised 1988. ISBN 0-8129-1726-X.

- Eicher, John and David Eicher, Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3

- Warner, Ezra J., Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders, Louisiana State University Press, 1964, ISBN 0-8071-0822-7

- Warner, Ezra J., Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders, Louisiana State University Press, 1959, ISBN 0-8071-0823-5

- Waugh, John C., The Class of 1846, From West Point to Appomattox: Stonewall Jackson, George McClellan and their Brothers, New York: Warner, 1994. ISBN 0-446-51594-9

Further reading

- American National Biography (20 vol. 2000; online and paper copies at academic libraries) short biographies by specialists

- Current, Richard N., et al. eds. Encyclopedia of the Confederacy (1993) (4 Volume set; also 1 vol abridged version) (ISBN 0-13-275991-8)

- Dictionary of American Biography 30 vol, 1934–1990; short biographies by specialists

- Faust, Patricia L. (ed.) Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War (1986) (ISBN 0-06-181261-7) 2000 short entries

- Heidler, David Stephen. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History (2002), 1600 entries in 2700 pages in 5 vol or 1-vol editions

- Woodworth, Steven E. ed. American Civil War: A Handbook of Literature and Research (1996) (ISBN 0-313-29019-9), 750 pages of historiography and bibliography