Milinda Panha

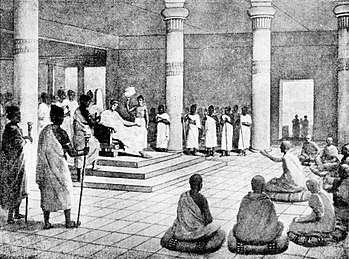

The Milinda Pañha (Pali: मिलिन्द पञ्ह; translated as "Questions of Milinda") is a Buddhist text which dates from approximately 100 BCE. Milinda Pañha purports to record a dialogue between the Buddhist sage Nāgasena, and the Indo-Greek king Menander I (Pali: Milinda) of Bactria, who reigned from Sagala (modern Sialkot, Pakistan).

Milinda Pañha is included in the Burmese edition of the Pāli Canon of Theravada Buddhism as part of the book of Khuddaka Nikaya. An abridged version is included as part of Chinese Mahayana translations of the canon. The Milinda Pañha does not appear in the Thai or Sinhala versions of the Pāli Canon, however.

History

The earliest part of the text is believed to have been written between 100 BCE and 200 CE.[1] The text may have initially been written in Sanskrit;[2] however, apart from the Sri Lankan Pali edition and its derivatives, no other copies are known.

It is generally accepted by scholars[3] that the work is composite, with additions made over some time. In support of this, it is noted that the Chinese versions of the work are substantially shorter.[4]

The oldest manuscript of the Pali text was copied in 1495 CE. Based on references within the text itself, significant sections of the text are lost, making Milinda the only Pali text known to have been passed down as incomplete.[5]

The book is included in the inscriptions of the Canon approved by the Burmese Fifth Council and the printed edition of the Sixth Council text.

Rhys Davids says it is the greatest work of classical Indian prose,[6] though Moritz Winternitz says this is true only of the earlier parts.[7]

Contents

The contents of the Milindapañhā are:

- Background History

- Questions on Distinguishing Characteristics : (Characteristics of Attention and Wisdom, Characteristic of Wisdom, Characteristic of Contact, Characteristic of Feeling, Characteristic of Perception, Characteristic of Volition, Characteristic of Consciousness, Characteristic of Applied Thought, Characteristic of Sustained Thought, etc.)

- Questions for the Cutting Off of Perplexity : (Transmigration and Rebirth, The Soul, Non-Release From Evil Deeds, Simultaneous Arising in Different Places, Doing Evil Knowingly and Unknowingly, etc.)

- Questions on Dilemmas : Speaks of several puzzles and these puzzles were distributed in eighty-two dilemmas.

- A Question Solved By Inference

- Discusses the Special Qualities of Asceticism

- Questions on Talk of Similes

According to Oskar von Hinüber (2000), while King Menander is an actual historical figure, Bhikkhu Nagasena is otherwise unknown, the text includes anachronisms, and the dialogue lacks any sign of Greek influence but instead is traceable to the Upanisads.[8]

The text mentions Nāgasena's father Soñuttara, his teachers Rohana, Assagutta of Vattaniya and Dhammarakkhita of Asoka Ārāma near Pātaliputta, and another teacher named Āyupāla from Sankheyya near Sāgala.

Menander I

According to the Milindapanha, Milinda/ Menander (who could be either Menander I or Menander II), embraced the Buddhist faith. He is described as constantly accompanied by a guard of 500 Greek ("Yonaka") soldiers, and two of his counsellors are named Demetrius and Antiochus.

In the Milindanpanha, Menander is introduced as:

King of the city of Sâgala in India, Milinda by name, learned, eloquent, wise, and able; and a faithful observer, and that at the right time, of all the various acts of devotion and ceremony enjoined by his own sacred hymns concerning things past, present, and to come. Many were the arts and sciences he knew--holy tradition and secular law; the Sânkhya, Yoga, Nyâya, and Vaisheshika systems of philosophy; arithmetic; music; medicine; the four Vedas, the Purânas, and the Itihâsas; astronomy, magic, causation, and magic spells; the art of war; poetry; conveyancing in a word, the whole nineteen. As a disputant he was hard to equal, harder still to overcome; the acknowledged superior of all the founders of the various schools of thought. And as in wisdom so in strength of body, swiftness, and valour there was found none equal to Milinda in all India. He was rich too, mighty in wealth and prosperity, and the number of his armed hosts knew no end.

Buddhist tradition relates that, following his discussions with Nāgasena, Menander adopted the Buddhist faith:

May the venerable Nâgasena accept me as a supporter of the faith, as a true convert from to-day onwards as long as life shall last!— The Questions of King Milinda, Translation by T. W. Rhys Davids, 1890

He then handed over his kingdom to his son and retired from the world:

And afterwards, taking delight in the wisdom of the Elder, he handed over his kingdom to his son, and abandoning the household life for the houseless state, grew great in insight, and himself attained to Arahatship!— The Questions of King Milinda, Translation by T. W. Rhys Davids, 1890

Translations

The work has been translated into English twice, once in 1890 by Thomas William Rhys Davids (reprinted by Dover Publications in 1963) and once in 1969 by Isaline Blew Horner (reprinted in 1990 by the Pali Text Society).

- Questions of King Milinda, tr T. W. Rhys Davids, Sacred Books of the East, volumes XXXV & XXXVI, Clarendon/Oxford, 1890–94; reprinted by Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi Vol. 1, Vol. 2

- Milinda's Questions, tr I. B. Horner, 1963-4, 2 volumes, Pali Text Society, Bristol

Abridgements include:

- Pesala, Bhikkhu (ed.), The Debate of King Milinda: An Abridgement of the Milindapanha. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1992. Based on Rhys Davids (1890, 1894).

- Mendis, N.K.G. (ed.), The Questions of King Milinda: An Abridgement of the Milindapanha. Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society, 1993 (repr. 2001). Based on Horner (1963–64).

See also

| Pāli Canon |

|---|

| Vinaya Pitaka |

| Sutta Pitaka |

| Abhidhamma Pitaka |

| Part of a series on |

| Theravāda Buddhism |

|---|

|

Notes

- ↑ Hinuber (2000), pp. 85-6, para. 179.

- ↑ Hinüber (2000), p. 83, para. 173, suggests, based on an extant Chinese translation of Mil as well as some unique conceptulizations within the text, the text's original language might have been Gandhari.

- ↑ Hinüber (2000), pp. 83-86, para. 173-179.

- ↑ According to Hinüber (2000), p. 83, para. 173, the first Chinese translation is believed to date from the 3rd century and is currently lost; a second Chinese translation, known as "Nagasena-bhiksu-sutra," (那先比丘經) dates from the 4th century. The extant second translation is "much shorter" than that of the current Pali-language Mil.

- ↑ Hinuber (2000), p. 85, para. 178.

- ↑ Rhys Davids (1890, 1894), p. xlviii, writes: "[T]he 'Questions of Milinda' is undoubtedly the masterpiece of Indian prose, and indeed is the best book of its class, from a literary point of view, that had then been produced in any country."

- ↑ History of Indian Literature

- ↑ von Hinuber (2000), p. 83, para. 172.

- ↑ The coins of the Greek and Scythic kings of Bactria and India in the British Museum, p.50 and Pl. XII-7

Sources

- Hinüber, Oskar von (1996/2000). A Handbook of Pāli Literature. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016738-7.

- Winternitz, Moritz. History of Indian Literature.

External links

- The Questions of King Milinda, translated by Thomas William Rhys Davids. at Sacred-texts.com.

- The Debate of King Milinda, Most Recent HTML and PDF Editions.

- The Debate of King Milinda, Abridged Edition. Bhikkhu Pesala. Hosted at BuddhaNet.

- Milindapañha - Selected passages in both Pali and English, translated by John Kelly

- Milinda Panha Sinhalese translation