Meldonium

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Mildronate, Mildronāts |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Synonyms | THP, MET-8 Mildronāts or Quaterine |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.224.143 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6H14N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 147.19 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Solubility in water | >40 mg/mL mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

Meldonium (INN), trade-named as Mildronate among others, is a limited-market pharmaceutical, developed in 1970 by Ivars Kalviņš, Latvian Institute of Organic Synthesis (USSR), and manufactured primarily by Grindeks of Latvia and several generic manufacturers. It is distributed in Eastern European countries as an anti-ischemia medication.[1]

Since 1 January 2016, it has been on the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) list of substances banned from use by athletes.[2] However, there are debates over its use as an athletic performance enhancer. Some athletes are known to have been using it before it was banned.[3] It is currently unscheduled in the US.

Medical use

Meldonium may be used to treat coronary artery disease.[4][5] These heart problems may sometimes lead to ischemia, a condition where too little blood flows to the organs in the body, especially the heart. Because this drug is thought to expand the arteries, it helps to increase the blood flow as well as increase the flow of oxygen throughout the body.[6] Meldonium has also been found to induce anticonvulsant and antihypnotic effects involving alpha 2-adrenergic receptors as well as nitric oxide-dependent mechanisms. This, in summary, shows that meldonium given in acute doses could be beneficial for the treatment of seizures and alcohol intoxication.[7] It is also used in cases of cerebral ischemia, ocular ischemic syndrome and other ocular disease caused by disturbed arterial circulation and may also have some effect on decreasing the severity of withdrawal symptoms caused by the cessation of chronic alcohol use.

Physio-pharmacology

Meldonium is believed to exert its cardioprotective effects through its ability to cause vasodilation in the coronary arteries via increased nitric oxide synthesis, reducing blood glucose concentrations through increased oxidation of glucose and also by preconditioning the heart to handle ischaemic situations, among other effects. It also has been implicated in the use of cerebral ischaemia. This is all done through its inhibition of carnitine synthesis.

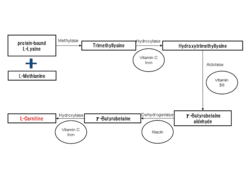

To ensure a continuous guarantee of energy supply, the body oxidises considerable amounts of fat besides glucose. Carnitine transports activated long-chain fatty acids (FA) from the cytosol of the cell into the mitochondrion and is therefore essential for fatty acid oxidation (known as beta oxidation). Carnitine is mainly absorbed from the diet, but can be formed through biosynthesis. To produce carnitine, lysine residues are methylated to trimethyllysine. Four enzymes are involved in the conversion of trimethyllysine and its intermediate forms into the final product of carnitine. The last of these 4 enyzmes is Gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase (GBB), which hyroxylates butyrobetaine into carnitine.

The main cardioprotective effects are mediated by the inhibition of the enzyme GBB. By subsequently inhibiting carnitine biosynthesis, fatty acid transport is reduced and the accumulation of cytotoxic intermediate products of fatty acid beta-oxidation in ischemic tissues to produce energy is prevented, therefore blocking this highly oxygen-consuming process.[8] Treatment with meldonium therefore shifts the myocardial energy metabolism from fatty acid oxidation to the more favorable oxidation of glucose, or glycolysis, under ischemic conditions. It also reduces the formation of Trimethylamine N-oxide, a product of carnitine breakdown and implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and congestive heart failure.

In fatty acid (FA) metabolism, long chain fatty acids in the cytosol cannot cross the mitochondrial membrane because they are negatively charged. The process in which they move into the mitochondria is called the carnitine shuttle. Long chain FA are first activated via esterification with coenzyme A to produce a fatty acid-coA complex which can then cross the external mitochondrial border. The co-A is then exchanged with carnitine (via the enzyme carnitine palmitoyltransferase I) to produce a fatty acid-carnitine complex. This complex is then transported through the inner mitochondrial membrane via a transporter protein called carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase. Once inside, carnitine is liberated (catalysed by the enzyme carnitine palmitoyltransferase II) and transported back outside so the process can occur again. Acylcarnitines like palmitoylcarnitine are produced as intermediate products of the carnitine shuttle.

In the mitochondria, the effects of the carnitine shuttle are reduced by meldonium, which competitively inhibits the SLC22A5 transporter. This results in reduced transportation and metabolism of long-chain fatty acids in the mitochondria (this burden is shifted more to peroxisomes). The final effect is a decreased risk of mitochondrial injury from fatty acid oxidation and a reduction of the production of acylcarnitines, which has been implicated in the development of insulin resistance.[9][10] Because of its inhibitory effects on L-carnitine biosynthesis and its subsequent glycolytic effects as well as reduced acylcarnitine production, meldonium has been indicated for use in diabetic patients. Long term use has been shown to reduce blood glucose concentrations, exhibit cardioprotective effects and prevent or reduce the severity of diabetic complications.[11] Long term treatment has also been shown to attenuate the development of atherosclerosis in the heart.

Its vasodilatory effects are stipulated to be due to the stimulation of the production of nitric oxide in the vascular endothelium. It is hypothesized that meldonium may increase the formation of the gamma-butyrobetaine esters, potent parasympathomimetics and may activate the eNOS enzyme which causes nitric oxide production via stimulation of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor or specific gamma-butyrobetaine ester receptors.[12]

Meldonium is believed to continually train the heart pharmacologically, even without physical activity, inducing preparation of cellular metabolism and membrane structures (specifically in myocardial mitochondria[13]) to survive ischemic stress conditions. This is done by adapting myocardial cells to lower fatty acid inflow and by activating glycolysis; the heart eventually begins using glycolysis instead of beta oxidation during real life ischaemic conditions. This reduces oxidative stress on cells, formation of cytotoxic products of fatty acid oxidation and subsequent cellular damage. This has made meldonium a possible pharmacological agent for ischemic preconditioning.[14]

How the central nervous system effects of meldonium is brought about is unclear. Studies have shown that meldonium increases cognition and mental performance by reducing amyloid beta deposition in the hippocampus.[15]

Pharmacology

Although initial reports suggested meldonium is a non-competitive and non-hydroxylatable analogue of gamma-butyrobetaine;[16] further studies have identified that meldonium is a substrate for gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase.[17][18][19] X-ray crystallographic and in vitro biochemical studies suggest that meldonium binds to the substrate pocket of γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase and acts as an alternative substrate, and therefore a competitive inhibitor.[20] Normally, this enzyme's action on its substrates γ-butyrobetaine and 2-oxoglutarate gives, in the presence of the further substrate oxygen, the products L-carnitine, succinate, and carbon dioxide; in the presence of this alternate substrate, the reaction yields malonic acid semialdehyde, formaldehyde (akin to the action of histone demethylases), dimethylamine, and (1-methylimidazolidin-4-yl)acetic acid, "an unexpected product with an additional carbon-carbon bond resulting from N-demethylation coupled to oxidative rearrangement, likely via an unusual radical mechanism."[20][19] The unusual mechanism is thought likely to involve a Steven's type rearrangement.[18]

Meldonium's inhibition of γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase gives a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of 62 micromolar, which other study authors have described as "potent."[21][22] Meldonium is an example of an inhibitor that acts as a non-peptidyl substrate mimic.[23]

Chemistry

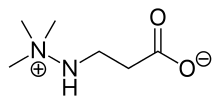

The chemical name of meldonium is 3-(2,2,2-trimethylhydraziniumyl) propionate.[24][25] It is a structural analogue of γ-butyrobetaine, with an amino group replacing the C-4 methylene of γ-butyrobetaine. γ-Butyrobetaine is a precursor in the biosynthesis of carnitine.[26]

It has a molecular weight of 146.188. It is available as a white crystalline powder, as well as a capsule sold by Grindeks. The melting point is anywhere between 85-90 degrees Celsius.[27]

Society and culture

Doping

Meldonium was added to the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) list of banned substances effective 1 January 2016 because of evidence of its use by athletes with the intention of enhancing performance.[2][28] It was on the 2015 WADA's list of drugs to be monitored.[29][30] An alarmingly high prevalence of meldonium use by athletes in sport was demonstrated by the laboratory findings at the Baku 2015 European Games. 13 medallists or competition winners were taking meldonium at the time of the Baku Games. Meldonium use was detected in athletes competing in 15 of the 21 sports during the Games. Most of the athletes taking meldonium withheld the information of their use from anti-doping authorities by not declaring it on their doping control forms as they should have. Only 23 of the 662 (3.5%) athletes tested declared the personal use of meldonium. However, 66 of the total 762 (8.7%) of athlete urine samples analysed during the Games and during pre-competition tested positive for meldonium.[31]

WADA classes the drug as a metabolic modulator, just as it does insulin.[32] Metabolic modulators are classified as S4 substances according to the WADA banned substances list. These substances have the ability to modify how some hormones accelerate or slow down different enzymatic reactions in the body. In this way, these modulators can block the body's conversion of testosterone into oestrogen, which is necessary for females. Based on the overall effects these drugs have, they have been banned since 2001 from men's competitions and 2005 for women's.[33] On April 13, 2016 it was reported that WADA had issued updated guidelines allowing less than 1 microgram per milliliter of meldonium for tests done before March 1, 2016.[34] The agency cited that "preliminary tests showed that it could take weeks or months for the drug to leave the body".

Affected athletes

On March 7, 2016, former world number one tennis player Maria Sharapova announced that she had failed a drug test in Australia due to the detection of meldonium. She said that she had been taking the drug for ten years for various health issues, and had not noticed that it had been banned.[35][36] On June 8, 2016, she was suspended from playing tennis for two years by the International Tennis Federation (ITF).[37][38][39] Earlier the same year (March 7), Russian ice dancer Ekaterina Bobrova announced that she had also tested positive for meldonium at the 2016 European Figure Skating Championships. Bobrova said she was shocked about the test result, because she had been made aware of meldonium's addition to the banned list, and had been careful to avoid products containing banned substances.[40] In May 2016, Russian professional boxer Alexander Povetkin — a former two-time World Boxing Association (WBA) Heavyweight Champion— tested positive for meldonium. This was discovered just a week prior to his mandatory title match against World Boxing Council (WBC) Heavyweight Champion, Deontay Wilder. As a result, the match—scheduled to take place in Povetkin's native Russia—was postponed indefinitely by the WBC.[41]

Other athletes who are provisionally banned for using meldonium include Ethiopian-Swedish middle-distance runner Abeba Aregawi,[42] Ethiopian long-distance runner Endeshaw Negesse,[43] Russian cyclist Eduard Vorganov,[44] and Ukrainian biathletes Olga Abramova[45] and Artem Tyshchenko.[46]

The Ice Hockey Federation of Russia replaced the Russia men's national under-18 ice hockey team with an under-17 team for the 2016 IIHF World U18 Championships after players on the original roster tested positive for meldonium.[47]

The World Anti-Doping Agency has recorded 124 positive samples with traces of meldonium since banning meldonium.[48] These include:[49]

| Name | Country | Sport | Where | Consequences | source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander Povetkin | | Boxing | mandatory challenger, World Boxing Council Heavyweight Title match | match canceled | |

| Maria Sharapova | | Tennis | 2016 Australian Open | Banned for two years, backdated to 26 January 2016. Reduced to 15 months. | [35][36] |

| Semion Elistratov | | Short track speed skating | No fault | [50] | |

| Pavel Kulizhnikov | | Speed skating | 2016 World Sprint Speed Skating Championships – Men | No fault | [50] |

| Alexander Markin | | Volleyball | Unknown | ||

| Eduard Vorganov | | Cycling | Unknown | ||

| Ekaterina Bobrova | | Figure skating | 2016 European Figure Skating Championships | No fault | [50] |

| Eduard Latypov | | Biathlon | Provisionally suspended | [44] | |

| Olga Abramova | | Biathlon | Unknown | [45] | |

| Artem Tyshchenko | | Biathlon | Unknown | [46] | |

| Davit Modzmanashvili | | Wrestling | Suspension temporarily lifted | ||

| Yekaterina Konstantinova | | Short track speed skating | No fault | [50] | |

| Abeba Aregawi | | Athletics | Unknown | [42] | |

| Endeshaw Negesse | | Athletics | Unknown | [43] | |

| Alexey Mikhaltsov | | Rugby sevens | Unknown | ||

| Alena Mikhaltsova | | Rugby sevens | Unknown | ||

| Nataliia Lupu | | Athletics | Unknown | ||

| Yuliya Yefimova | | Swimming | Two out of competition tests— 15 & 24 February | Unknown | [51] |

| Nadezhda Sergeeva | | Bobsleigh | Suspension temporarily lifted | ||

| Nadezhda Kotlyarova | | Athletics | Cleared by RUSADA | [52] | |

| Andrey Minzhulin | | Athletics | Cleared by RUSADA | [52] | |

| Gulshat Fazletdinova | | Athletics | Cleared by RUSADA | [52] | |

| Olga Vovk | | Athletics | Cleared by RUSADA | [52] | |

| Sergei Semenov | | Wrestling | Cleared by RUSADA | [52] | |

| Evgeny Saleev | | Wrestling | Unknown | [53] | |

| Anastasia Chulkova | | Cycling | Cleared by RUSADA | [52] | |

| Pavel Yakushevsky | | Cycling | Suspension temporarily lifted | [54] | |

| István Lévai | | Wrestling | Unknown | [55] | |

| Gabriela Petrova | | Athletics | 6 February 2016 | Suspension temporarily lifted | [56] |

| Alexey Bugaychuk | | Water polo | Unknown | [57] | |

| Pavel Kulikov | | Skeleton | Suspension temporarily lifted | [58] | |

| Andrei Rybakou | | Weightlifting | Unknown | [59] | |

| Nikolai Kuksenkov | | Artistic gymnastics | Unknown | [60] | |

| Denis Yartsev | | Judo | Unknown | [61] | |

| Mikhail Pulyaev | | Judo | Unknown | [61] | |

| Natalia Kondratieva | | Judo | Unknown | [61] | |

| Yekaterina Valkova | | Judo | Unknown | [61] | |

| Kirill Vichuzhanin | | Cross-country skiing | Unknown | [62] | |

| Igor Mikhalkin | | Boxing (professional) | 12 March 2016 | 2-year ban | [63] |

| Ruth Kasirye | | Weightlifting | Unknown | ||

| Petr Novak | | Wrestling | Unknown | [64] | |

| Elena Mirela Lavric | | Athletics | 2016 IAAF World Indoor Championships | Unknown | [65] |

| Éva Tófalvi | | Biathlon | Unknown | [66] | |

| Anastasiya Mokhnyuk | | Athletics | Unknown | [67] | |

| Islam Makhachev | | Mixed martial arts | Out of contest routine testing | Provisional suspension lifted after 75 days | [68] |

| Beka Lomtadze | | Wrestling | Suspension temporarily lifted | [69] | |

| Davit Chakvetadze | | Wrestling | Cleared by RUSADA | [69] | |

| Armantas Vitkauskas | | Football | unknown | [70] | |

| Martynas Dapkus | | Football | unknown | [70] | |

| Andrii Kviatkovskyi | | Wrestling | Provisionally suspended | [71] | |

| Alen Zasyeyev | | Wrestling | Provisionally suspended | [71] | |

| Oksana Herhel | | Wrestling | Provisionally suspended | [71] | |

| Varvara Lepchenko | | Tennis | No fault | [72] |

In addition it was reported that five Georgian wrestlers [73] and a German wrestler had tested positive for the drug although no further names were released.[74] On 25 March 2016 the Fédération Internationale de Sambo confirmed that four wrestlers under their governance (two from Russia and two from other countries) had recorded positive tests for the drug.[75]

Debates

A December 2015 study in the journal Drug Testing and Analysis argued that meldonium "demonstrates an increase in endurance performance of athletes, improved rehabilitation after exercise, protection against stress, and enhanced activations of central nervous system (CNS) functions".[76] It is opposing to steroids in the sense that instead of making the athlete emotionally unstable and readily irritable, it keeps them in an elevated state of mind and keeps their emotions in a happier state. When referring to central nervous system enhancements, it better activates the neurons in the CNS. This improves the messaging system throughout the body and, therefore, can decrease (improve) reaction time for an athlete.

The manufacturer, Grindeks, said in a statement that it did not believe meldonium’s use should be banned for athletes. It said the drug worked mainly by reducing damage to cells that can be caused by certain byproducts of carnitine. Meldonium “is used to prevent death of ischemic cells and not to increase performance of normal cells,” the statement said. “Meldonium cannot improve athletic performance, but it can stop tissue damage in the case of ischemia,” which is lack of blood flow to an area of the body.[77]

The drug was invented in the mid-1970s at the Institute of Organic Synthesis of the Latvian SSR Academy of Sciences by Ivars Kalviņš.[78][79][80] Kalviņš criticized the ban, saying that WADA had not presented scientific proof that the drug can be used for doping. According to him, meldonium does not enhance athletic performance in any way, and was rather used by athletes to prevent damage to the heart and muscles caused by lack of oxygen during high-intensity exercise. He contended that not allowing athletes to take care of their health was a violation of their human rights, and that the decision aimed to remove Eastern European athletes from competitions and his drug from the pharmaceutical market.[81][82] Liene Kozlovska, the head of the anti-doping department of the Latvian sports medicine center, rejected claims that the ban is in violation of athletes' rights, saying that meldonium is dangerous in high doses, and should only be used under medical supervision to treat genuine health conditions. She also speculated that Russian athletes may not have received adequate warnings that the drug was banned – due to the suspension of the Russian Anti-Doping Agency in late 2015.[83]

Forbes reported that anesthesiology professor Michael Joyner, at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, who studies how humans respond to physical and mental stress during exercise and other activities, told them that "Evidence is lacking for many compounds believed to enhance athletic performance. Its use has a sort of urban legend element and there is not much out there that is clearly that effective. I would be shocked if this stuff [meldonium] had an effect greater than caffeine or creatine (a natural substance that, when taken as a supplement, is thought to enhance muscle mass).”[84] Ford Vox, a U.S.-based physician specializing in rehabilitation medicine and a journalist reported "there's not much scientific support for its use as an athletic enhancer".[85]

Don Catlin, a long-time anti-doping expert and the scientific director of the Banned Substances Control Group (BSCG) said “There’s really no evidence that there’s any performance enhancement from meldonium - Zero percent.”[86]

Approval status

Meldonium, which is not approved by the FDA in the United States, is registered and prescribed in Latvia, Russia, Ukraine, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Uzbekistan, Moldova and Kyrgyzstan.[87][88]

Economics

Meldonium is manufactured by Grindeks, a Latvian pharmaceutical company, with offices in thirteen Eastern European countries[89] as a treatment for heart conditions.[90][91] The company identifies it as one of their main products.[92] It had sales of 65 million euros in 2013.[80]

References

- ↑ "Grindeks: We Believe that Meldonium Should not be Included in the List of Banned Substances in Sport". Grindeks. 9 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Prohibited List". World Anti-Doping Agency. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ↑ "All About Meldonium, the Banned Drug Used by Sharapova". New York Times. Associated Press. 8 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ↑ Sjakste, N; Gutcaits, A; Kalvinsh, I (2004). "Mildronate: an antiischemic drug for neurological indications.". CNS Drug Reviews. 11 (2): 151–68. PMID 16007237. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2005.tb00267.x.

- ↑ Dambrova, M; Makrecka-Kuka, M; Vilskersts, R; Makarova, E; Kuka, J; Liepinsh, E (2 February 2016). "Pharmacological effects of meldonium: Biochemical mechanisms and biomarkers of cardiometabolic activity.". Pharmacological research. PMID 26850121. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2016.01.019.

- ↑ Myocardial ischemia. Mayo Clinic (25 July 2015). Retrieved on 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Zvejniece, L; Svalbe, B; Makrecka, M; Liepinsh, E; Kalvinsh, I; Dambrova, M (2010). "Mildronate exerts acute anticonvulsant and antihypnotic effects". Behavioral Pharmacology. 21: 548–555. PMID 20661137. doi:10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833d5a59.

- ↑ Sjakste N, Gutsaits, Kalvinsh I (June 2005). "Mildronate: an antiischemic drug for neurological indications". CNS Drug Reviews. 11 (2): 151–68. PMID 16007237.

- ↑ Schooneman MG, van Groen T, Vaz FM, Houten SM, Soeters MR (January 2013). "Acylcarnitines: Reflecting or Inflicting Insulin Resistance?". Diabetes. 62 (1): 1–8. PMID 23258903. doi:10.2337/db12-0466.

- ↑ Lippi G, Mattiuzzi C (June 2016). "Misuse of the metabolic modulator meldonium in sports". Journal of Sport and Health Science. 5 (2): 1–3. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2016.06.008.

- ↑ Liepinsh E, Vilskersts R, Zvejniece L, Svalbe B, Skapare E, Kuka J, Cirule H, Grinberga S, Kalvinsh I, Dambrova M (August 2009). "Protective effects of mildronate in an experimental model of type 2 diabetes in Goto-Kakizaki rats". British Journal of Pharmacology. 157 (8): 1549–56. PMID 19594753. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00319.x.

- ↑ Sjakste N, Gutsaits, Kalvinsh I (June 2005). "Mildronate: an antiischemic drug for neurological indications". CNS Drug Reviews. 11 (2): 151–68. PMID 16007237.

- ↑ Kuka J, Vilskersts R, Cirule H, Makrecka M, Pugovics O, Kalvinsh I, Dambrova M, Liepinsh E (June 2012). "The cardioprotective effect of mildronate is diminished after co-treatment with L-carnitine". Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology and therapeutics. 17 (2): 215–22. PMID 21903968. doi:10.1177/1074248411419502.

- ↑ Dambrova, Liepinsh E, Kalvinsh I (August 2002). "Mildronate: cardioprotective action through carnitine-lowering effect". Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 12 (6): 275–9. PMID 12242052.

- ↑ Beitnere U, van Groen T, Kumar A, Jansone B, Klusa V, Kadish I (March 2014). "Mildronate improves cognition and reduces amyloid-β pathology in transgenic Alzheimer's disease mice.". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 92 (3): 338–46. PMID 24273007. doi:10.1002/jnr.23315.

- ↑ Galland, S; Le Borgne, F; Guyonnet, D; Clouet, P; Demarquoy, J (January 1998). "Purification and characterization of the rat liver gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase". Mol. Cell. Biochem. 178 (1–2): 163–8. PMID 9546596. doi:10.1023/A:1006849713407.

- ↑ PDB: 3O2G

- 1 2 Henry L, Leung IK, Claridge TD, Schofield CJ (August 2012). "γ-Butyrobetaine hydroxylase catalyses a Stevens type rearrangement". Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 22 (15): 4975–4978. PMID 22765904. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.06.024.

- 1 2 Spaniol, M; Brooks, H; Auer, L; Zimmermann, A; Solioz, M; Stieger, B; Krähenbühl, S (March 2001). "Development and characterization of an animal model of carnitine deficiency". Eur. J. Biochem. 268 (6): 1876–87. PMID 11248709. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02065.x.

- 1 2 Leung, IK; Krojer, TJ; Kochan, GT; Henry, L; von Delft, F; Claridge, TD; Oppermann, U; McDonough, MA; Schofield, CJ (December 2010). "Structural and mechanistic studies on γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase". Chemistry and Biology. 17 (12): 1316–24. PMID 21168767. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.09.016.

- ↑ Tars K, Rumnieks J, Zeltins A, Kazaks A, Kotelovica S, Leonciks A, Sharipo J, Viksna A, Kuka J, Liepinsh E, Dambrova M (August 2010). "Crystal structure of human gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 398 (4): 634–9. PMID 20599753. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.121.

- ↑ For a perspective from a Merck discovery biochemist on the clinical advantages of picomolar to nanomolar (i.e., thousand- to million-fold more potent) inhibitors, see Copeland, Robert A. (2005). "Tight Binding Inhibition; Potential Clinical Advantages of Tight Binding Inhibitors [Chapter 7, §7.8]". Evaluation of Enzyme Inhibitors in Drug Discovery: A Guide for Medicinal Chemists and Pharmacologists. Methods of Biochemical Analysis, Vol. 46. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley. pp. 206–209. ISBN 0471723266.

[Quoting:] If one is beginning this pharmacological optimization with compounds displaying very high target affinity, more flexibility in compromising affinity for other parameters can be exercised. Thus, if the starting molecule has picomolar affinity for the target enzyme, and nanomolar affinity will suffice, the researcher can afford to give up 1000-fold in target affinity for the sake of pharmacological optimization. … high affinity of …tight binding inhibitors allows one to minimize the dose of drug to which patients are exposed, thus limiting off-target based toxicities.

- ↑ Rose NR, McDonough MA, King ON, Kawamura A, Schofield CJ (2011). "Inhibition of 2-Oxoglutarate Dependent Oxygenases". Chemical Society Reviews. 40 (8; August): 4364–4397. PMID 21390379. doi:10.1039/c0cs00203h. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Pubchem. "Mildronate". nih.gov. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ↑ Simkhovich BZ, Shutenko ZV, Meirena DV, Khagi KB, Mezapuķe RJ, Molodchina TN, Kalviņs IJ, Lukevics E (January 1988). "3-(2,2,2-Trimethylhydrazinium)propionate (THP)--a novel gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase inhibitor with cardioprotective properties". Biochemical Pharmacology. 37 (2): 195–202. PMID 3342076. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(88)90717-4.

- ↑ Fraenkel G, Friedman S (1957). "Carnitine". Vitamins Hormones. Vitamins & Hormones. 15: 73–118. ISBN 9780127098159. PMID 13530702. doi:10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60508-7.

- ↑ Meldonium | C6H14N2O2. ChemSpider. Retrieved on 28 May 2016.

- ↑ "2016 Prohibited List, Summary of Major Modifications and Explanatory Notes" (PDF). World Anti-Doping Agency. 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "WADA updates list of banned substances". USA Today. Associated Press. 30 September 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ↑ "WADA 2015 Monitoring Program" (PDF). wada-ama.org. WADA. 1 January 2016.

- ↑ "Meldonium use by athletes at the Baku 2015 European Games". bmj.com. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ↑ "Prohibited List" (PDF). World Anti-Doping Agency. January 2016. S4:5.3. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ↑ S4 Hormone and metabolic modulators. Antidoping Switzerland.

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/14/sports/wada-meldonium-drug-testing.html

- 1 2 "Maria Sharapova admits to failing drug test, will be provisionally banned". CNN. 7 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Sharapova drug scandal: what is Meldonium". NewsComAu. 7 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ↑ "Maria Sharapova failed drugs test at Australian Open". BBC. 8 March 2016.

- ↑ "Press release: Tennis Anti-Doping Programme statement regarding Maria Sharapova". International Tennis Federation. 7 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ↑ "Maria Sharapova banned for two years for failed drugs test but will appeal". BBC. 8 June 2016.

- ↑ "Top Russian ice dancer Bobrova fails doping test – report". The Big Story. 7 March 2016.

- ↑ Rafael, Dan (16 May 2016). "Wilder-Povetkin called off after failed drug test". ESPN.com.

- 1 2 "Preparatet som kan fälla Aregawi". Sport. Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). 29 February 2016.

- 1 2 Butler, Nick (2 March 2016). "Ethiopian Tokyo Marathon winner Negesse reportedly fails drugs test for Meldonium". insidethegames.

- 1 2 Rogers, Neal (6 February 2016). "Second positive test in 12 months could see Katusha sidelined up to 45 days". cyclingtips.com.

- 1 2 "Ukrainian biathlete Abramova suspended in doping case". insidethegames. 10 February 2016.

- 1 2 "Tyshchenko named as second Ukrainian biathlete to fail doping test in 2016". insidethegames. 27 February 2016.

- ↑ "Russia replaces entire junior hockey team after drug scandal". Yahoo!. 13 April 2016.

- ↑ "WADA: 123 failed meldonium tests since January ban". en.as.com.

- ↑ Cambers, Simon (10 March 2016). "Why was Maria Sharapova taking meldonium? Her lawyer responds". theguardian.com. London.

- 1 2 3 4 "ISU Statement". ISU. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- ↑ Craig Lord (21 March 2016). "Yuliya Efimova Tells Russia “I’m Innocent” Despite Two Meldonium Positives in 2016". SwimVortex.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 TASS: Sport – RUSADA decides against disqualification of seven athletes for taking meldonium. Tass.ru (19 April 2016). Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- ↑ "Два российских борца попались на мельдонии".

- ↑ "Source: two Russian cyclists test positive for meldonium". Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Aj najlepší slovenský zápasník bral meldónium. Lévai do Ria asi nepôjde". Pravda (in Slovak). 30 March 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Хванаха с допинг най-добрата ни спортистка !". Topsport.bg. 27 March 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "TASS: Sport – Russian water polo player tests positive for meldonium — source". TASS. 30 March 2016.

- ↑ Pavel Kulikov è la 30° positività al meldonium dal caso di Maria Sharapova – Neve Italia. Neveitalia.it (1 April 2016). Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Белорусский тяжелоатлет Андрей Рыбаков попался на мельдонии – 01.04.2016 – Другие виды спорта – @. Sport.ru. Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Гимнаст, сменивший Украину на Россию, попался на употреблении мельдония – Новости спорта – Николай Куксенков был лидером сборной России по спортивной гимнастике | СЕГОДНЯ. Sport.segodnya.ua. Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Quatre judokas russes positifs au meldonium. ICI.Radio-Canada.ca (4 April 2016). Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Тренер Вичужанина подтвердил обнаружение мельдония в допинг-пробе спортсмена. Gazeta.ru (8 April 2016). Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Euro champ Igor Mikhalkin admits taking banned drug Meldonium. World Boxing News (11 April 2016). Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Czech wrestler Petr Novak tests positive for meldonium – Yahoo Sports. Sports.yahoo.com (12 April 2016). Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Призер ЧМ румынская бегунья Лаврик сдала положительный допинг-тест на мельдоний | Легкая атлетика | Р-Спорт. Все главные новости спорта. Rsport.ru. Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Eva Tofalvi des Dopings mit Meldonium überführt | Biathlon. Sport1.de. Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Украинская легкоатлетка Анастасия Мохнюк попалась на допинге – Новости спорта – Семиборка принимала препарат милдронат по назначению врача и считает себя невиновной | СЕГОДНЯ. Sport.segodnya.ua (14 April 2016). Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- ↑ "UFC Statement on Islam Makhachev". UFC.com.

- 1 2 Doping suspensions of 14 athletes lifted as meldonium concerns grow | Sport. The Guardian. Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- 1 2 LFF nenustatė žaidėjų kaltės dėl antidopingo taisyklių pažeidimo. Futbolas.lt (19 April 2016). Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 У Украины отобрали три олимпийские лицензии – ОИ Рио 2016 – Наши борцы попались на употреблении допинга. Sport.segodnya.ua (12 May 2016). Retrieved on 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Rothenberg, Ben (20 September 2016). "Varvara Lepchenko Is Cleared in Meldonium Inquiry". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ "Seis luchadores georgianos dan positivo por Meldonium" (in Spanish). El Dia.es. 15 February 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ "A German wrestler tests positive for meldonium". nzherald.co.nz. 17 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ "TASS: Sport – Two Russian Sambo wrestlers test positive for banned meldonium drug — executive". TASS. 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Görgens, Christian; Guddat, Sven; Dib, Josef; Geyer, Hans; Schänzer, Wilhelm; Thevis, Mario (2015). "Mildronate (Meldonium) in professional sports – monitoring doping control urine samples using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography – high resolution/high accuracy mass spectrometry". Drug Testing and Analysis. 7 (11–12): 973–979. PMID 25847280. doi:10.1002/dta.1788.

- ↑ "Meldonium Ban Hits Russian Athletes Hard". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ↑ "Scientific Board". osi.lv. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ↑ "Ivars Kalvins: A broad range of medicines based on natural compounds, spearheading a new generation of drugs". European Inventor Awards. Candidates in the Lifetime Achievement category. European Patent Office. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- 1 2 Niiler, Eric. "The Quirky History of Meldonium". Wired (website). Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ↑ "Изобретатель мельдония назвал две причины решения WADA" [Meldonium inventor named two reasons for WADA decision]. vesti.ru (in Russian). Russia. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ↑ Kristīna, Hudenko (8 March 2016). "Mildronāta radītājs Ivars Kalviņš: meldonija pielīdzināšana dopingam ir cilvēktiesību pārkāpums" (in Latvian). Delfi. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ↑ "Antidopinga eksperte: Mildronāts iekļauts aizliegto vielu sarakstā" (in Latvian). Diena. 8 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ↑ Rita Rubin. "Banned drug Sharapova took is widely used, study shows, despite little evidence that it boosts performance". Forbes. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ↑ Ford Vox. "Sharapova suspension: doping agency's unfair game of 'gotcha'?". CNN. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ "Experts say there's little evidence meldonium enhances performance". USA Today. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Banned Drug Sharapova Took Is Widely Used, Study Shows, Despite Little Evidence That It Boosts Performance". Forbes.

- ↑ Görgens C, Guddat S, Dib J, Geyer H, Schänzer W, Thevis M (November–December 2015). "Mildronate (Meldonium) in professional sports – monitoring doping control urine samples using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography – high resolution/high accuracy mass spectrometry". Drug Testing and Analysis. 7 (11–12): 973–979. PMID 25847280. doi:10.1002/dta.1788.

- ↑ "Branches and Representative Offices". Grindeks. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ↑ "AS "Grindeks" ir vadošais zāļu ražotājs Baltijas valstīs." (in Latvian). Grindeks. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ↑ Niiler, Eric (9 March 2016). "The Original Users of Sharapova's Banned Drug? Soviet Super Soldiers". Science. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ↑ "Mildronate". Grindeks. 9 March 2016.