Mihrimah Sultan

| Mihrimah Sultan مهر ماه سلطان | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Portrait by Cristofano dell'Altissimo titled Cameria Solimani, 16th century | |

| Born |

c. 1522 Istanbul, Ottoman Empire |

| Died |

25 January 1578 (aged 55–56) Istanbul, Ottoman Empire |

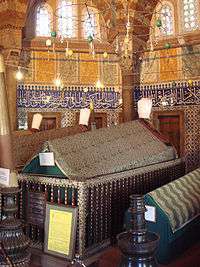

| Burial | Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul |

| Spouse | Damat Rüstem Pasha |

| Issue | Ayşe Hümaşah Sultan |

| Dynasty | Ottoman |

| Father | Suleiman the Magnificent |

| Mother | Hürrem Sultan |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Mihrimah Sultan (Ottoman Turkish: مهر ماه سلطان, Turkish pronunciation: [mihɾiˈmah suɫˈtan]) (c. 1522 – 25 January 1578) was an Ottoman princess, the daughter of Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and his legal wife, Hürrem Sultan.[1][2] She was the most powerful imperial princess in Ottoman history and one of the prominent figures during the Sultanate of Women.

Name

Mihrimah[lower-roman 1] Sultan's name means "Sun (lit. clemency, compassion, endearment, affection) and Moon". To Westerners, she was known as Cameria. Her portrait by Cristofano dell’Altissimo entitled as Cameria Solimani.

Other Ottoman imperial princesses who also named “Mihrimah” and also Mihrimah Sultan's close relative were:

- Mihrimah's niece, daughter of Şehzade Bayezid (son of Suleiman the Magnificent; Mihrimah's younger full-brother)

- Mihrimah's grandniece, daughter of Murad III (son of Selim II; Mihrimah's nephew)

Biography

.jpg)

Mihrimah was born in Istanbul in 1522 during the reign of her father, Suleiman the Magnificent. Her mother was Hürrem Sultan, an Orthodox priest's daughter, who was the current Sultan's concubine at the time. In 1533 or 1534, her mother, Hürrem, was freed and became Suleiman's legal wife.[3]

On 26 November 1539 in Istanbul at the age of seventeen, Mihrimah was married to Rüstem, a devshirme from Croatia who rose to become Governor of Diyarbakır and later, Suleiman's Grand Vizier.[4] Her wedding ceremony and the celebration for her younger brother Bayezid's circumcision occurred on the same day.[5] Five years later, her husband was selected by Suleiman to become Grand Vizier. Though the union was unhappy, Mihrimah flourished as a patroness of the arts and continued her travels with her father until her husband's death.

Mihrimah was not like other imperial princesses in Ottoman history. She was active in political affairs even in foreign courts and had access to considerable economic resources. She also became chief of Ottoman Imperial Harem during the reign of Selim II. Her position running the affairs of the harem in the same manner as the sultan's mother put Mihrimah at the top of the harem hierarchy during the reign of Selim II.

Political affairs

Mihrimah traveled throughout the Ottoman Empire with her father as he surveyed the lands and conquered new ones. In international politics, Hürrem Sultan sent letters to Sigismund II, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, and the contents of her letters were mirrored in letters written by Mihrimah, and sent by the same courier, who also carried letters from the sultan and her husband Rüstem Pasha the Grand Vizier.[2] Therefore, it is most probable that Hürrem and Mihrimah were well known even among ordinary Ukrainians.[6]

One of the popular, and also controversial story about Mihrimah was about her rivalry with her half-brother Şehzade Mustafa, the son of Mahodevran sultan. Along with her mother Hürrem, her husband Rüstem—who was the Grand Vizier—made a strong alliance and became dominated power in divan and inner circle of palace. Unfortunately for Mustafa, this condition became a great obstacle for him to access to the throne, although he was supported by Janissaries.

Although there is no proof of Hürrem or Mihrimah’s direct involvement, Ottoman sources and foreign accounts indicate that it was widely believed that the three worked first to eliminate Mustafa so as ensure the throne to Hürrem’s son and Mihrimah’s full-brother, Bayezid.[2] The rivalry ended in a loss for Mustafa when he was executed by his own father’s command in 1553 during the campaign against Safavid Persia because of fear of rebellion. Although this stories were not based on first-hand sources,[3] this fear of Mustafa was not unreasonable. Had Mustafa ascended to the throne, all Mihrimah’s full-brothers (Selim, Bayezid, and Cihangir) would have likely been executed, according to the fratricide custom of the Ottoman dynasty, which required all brothers of the new sultan be executed to avoid feuds among imperial siblings.[6]

Mihrimah also became Suleiman’s advisor, his confidant and his closest relative, especially after Suleiman’s other relatives and companions died or were exiled one by one, like Mustafa (executed in October 1553), Mahidevran (lost her status in the palace after Mustafa’s death and went to Bursa), Cihangir (died in November 1553), Hürrem (died in April 1558), Rüstem (died in July 1561), Bayezid (executed in September 1561), and Gülfem (died in 1561 or 1562). After Hürrem’s death, Mihrimah took her mother’s place as her father's councelor, urging him to undertake the conquest of Malta and sending him news and forwarding letters for him when he was absent from capital.[2]

Economic power

Beside her great political intelligence, Mihrimah also had access to considerable economic resources and often funded major architectural projects. She promised to build 400 galleys at her own expense to encourage Suleiman in his campaign against Malta. When her brother ascended to the throne as Selim II, she lent him some 50,000 gold sovereigns to sate his immediate needs.

Mihrimah also sponsored a number of major architectural projects. Her most famous foundations are the two Istanbul-area mosque complexes that bear her name, both designed by her father's chief architect, Mimar Sinan. Mihrimah Sultan Mosque (Turkish: Mihrimah Sultan Camii), also known as İskele Mosque (Turkish: Iskele Camii), which is one of Üsküdar's most prominent landmarks and was built between 1546 and 1548. The second mosque is also named as Mihrimah Sultan Mosque at the Edirne Gate, at the western wall of the old city of Istanbul, was one of Sinan's most imaginative designs, using new support systems and lateral spaces to increase the area available for windows. Its building took place from 1562 to 1565.

There is a myth about these two Mosques. It is said that Mimar Sinan fell in love with Mihrimah and built the smaller mosque in Edirnekapı without palace approval, on his own, dedicated to his love. The legend continues to say that on 21 March (when daytime and nighttime are equal and Mihrimah's alleged birthday, hence the name) at the time of sunset, if you have clear view of both mosques, you will notice that as the sun sets behind the only minaret of the mosque in Edirnekapı, the moon rises between the two minarets of the mosque in Üsküdar. Even became historical debates claiming if that is real or not, this story has become one of Istanbul's popular urban legends until now.

Later life and death

Mihrimah’s life was uncertain after Selim’s death in 1574. First opinion says that Mihrimah lost all her power and retired at the Old Palace. Other opinion says that Mihrimah kept her position at Topkapı Palace and continued to share her power with Nurbanu, the new Valide Sultan, until her own death, although she and also other imperial princesses were ranked under Nurbanu Sultan (Murad’s mother) and Safiye Sultan (Murad’s wife) in the royal court.

Mihrimah died in Istanbul on 25 January 1578 during the reign of her nephew Murad III, outliving all of her siblings. She was buried in Süleyman Mosque complex.

In popular culture

- In the 2011–2014 TV series Muhteşem Yüzyıl, she is portrayed by Pelin Karahan.

- In The Architect's Apprentice, a 2014 novel by Elif Şafak, she is a central character.

Notes

- ↑ Alternate spellings are Mihrumah, Mihr-î-Mâh, Mihrî-a-Mâh or Mehr-î-Mâh.

References

- ↑ "The Imperial House of Osman: Genealogy". Archived from the original on 2 May 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 Peirce, Leslie P. (1993). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508677-5.

- 1 2 Yermolenko, Galina (April 2005). "Roxolana: "The Greatest Empresse of the East". DeSales University, Center Valley, Pennsylvania.

- ↑ Vovchenko, Denis (2016-07-18). Containing Balkan Nationalism: Imperial Russia and Ottoman Christians, 1856-1914. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-061291-7.

- ↑ Peirce 1993, p. 123.

- 1 2 Yermolenko, Galina I. (1988). Roxolana in Europan Literature, History and Culture. Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Bibliography

- Imperial Harem : Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire 1993 by Leslie Peirce, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-508677-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mihrimah Sultan. |

- Photos of Mihrimah Sultan Mosque in Edirnekapi

- Photos of Iskele Mosque (aka Mihrimah) in Uskudar

- Mihrimah Sultan Mosque in Edirnekapi

- Mihrimah Sultan -- an Ottoman princess’ legacy survives