Mictlan

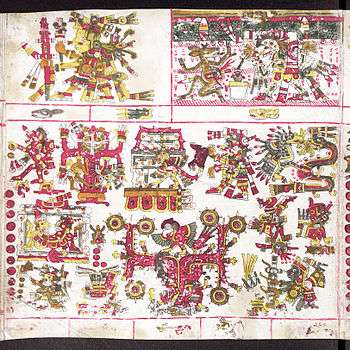

Mictlan (Nahuatl pronunciation: [ˈmikt͡ɬaːn]) was the underworld of Aztec mythology. Most people who died went to Mictlan, although other possibilities existed (see "Other Destinations," below).[1] Mictlan consisted of nine distinct levels.[1]

The journey from the first level to the ninth was difficult and took four years, but the dead were aided by the psychopomp, Xolotl. The dead had to pass many challenges, such as crossing a mountain range where the mountains crashed into each other, a field with wind that blew flesh-scraping knives, and a river of blood with fearsome jaguars.

Mictlan also features in the Aztec creation myth. Mictlantecuhtli set a pit to trap Quetzalcoatl. When Quetzalcoatl entered Mictlan, Mictlantecuhtli was waiting. He asked Quetzalcoatl to travel around Mictlan four times blowing a conch shell with no holes. Quetzalcoatl eventually put some bees in the conch shell to make sound. Fooled, Mictlantecuhtli showed Quetzalcoatl to the bones. But Quetzalcoatl fell into the pit and some of the bones broke. The Aztecs believed this is why people's height are different.

Mictlan was ruled by King Mictlantecuhtli ("Lord of the Underworld")[2] and his wife, Mictecacihuatl ("Lady of the Underworld").[3]

Other deities in Mictlan included Cihuacoatl (who commanded Mictlan spirits called Cihuateteo), Acolmiztli, Chalmecacihuilt, Chalmecatl and Acolnahuacatl.

Relationship to Nahuatl creation mythology

The nine regions of Mictlán (also known as Chiconauhmictlán) in Aztec mythology take shape within the Nahua worldview of space and time as parts of a universe composed of living forces. According to Mexica mythology, in the beginning there were two primordial gods, Omecíhuatl and Ometecuhtli, whose children became the creator gods. The names of these creator gods were Xipetótec, Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcóatl, and Huitzilopochtli, and they inherited the art of creation from their parents. From the preexisting matter, after 600 years of inactivity Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcóatl organized the vertical and horizontal universes, where the horizontal universe was composed of cardinal or hemispheric directions and the vertical universe was composed of two parts, a higher and a lower. The higher part was supported by four gigantic trees, growing in each corner of the Tlalocán (the central part of the universe). Such imagery is also found in the idea of a world tree, such as Yggdrasil in Norse mythology, Jian Mu in Chinese mythology or the Ashvattha fig in Hindu mythology. These trees impeded the joining of the Overworld (the higher world) and the Underworld (the lower world) to Tlaltícpac (the earth). The earth was a land formed from the body of Cipactli, the crocodilomorphic sea monster, and was a solid, living land that generated food for humankind. Cipactli was mother nature, from whom was created the surface and soil that was Tlaltícpac.[4]

The myth recounts the following. From Cipactli's hair sprang trees, flowers and plants, from her skin sprang plains, valleys and river sediments, from her eyes came wells, caves and fountains, from her mouth sprang rivers, lakes and streams, from her nose came valleys, ranges and mesas, from her shoulders the saw-toothed mountain ranges, volcanoes and mountains. As they organized the universe horizontally and vertically, the four creator gods forged the pairs[5] of gods who would control each area of power: the water (Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue), the earth (Tlaltecuhtli and Tlalcíhuatl), fire (Xiuhtecuhtli and Chantico) and the dead (Mictlantecuhtli and Mictecacíhuatl).

Other destinations

In addition to Mictlan, the dead could also go to other destinations:

- Warriors who died in battle and those who died as a sacrifice went east and accompanied the sun during the morning.[1]

- Women who died in childbirth went to the west and accompanied the sun when it set in the evening.[6]

- People who died of drowning — or from other causes that were linked to the rain god Tlaloc, such as certain diseases and lightning — went to a paradise called Tlalocan.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Smith, M. E. (2009). The Aztecs (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-631-23016-8

- ↑ Smith, M. E. (2009). The Aztecs (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-631-23016-8

- ↑ Soustelle, Jacques (Patrick O'Brian, translator) (1961). Daily Life of the Aztecs on the Eve of the Spanish Conquest. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 107.

- ↑ Hall, L. (1975). The Cipactli Monster: Woman as Destroyer in Carlos Fuentes. Southwest Review,60(3), 246-255. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43471223

- ↑ Stross, B. (1983). Oppositional Pairing in Mesoamerican Divinatory Day Names. Anthropological Linguistics, 25(2), 211-273. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/30027669

- ↑ Coe, Michael D. (1994). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs (4 ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. p. 183.