Estradiol (medication)

| |||

| |||

| Clinical data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌɛstrəˈdaɪoʊl/ ES-trə-DYE-ohl[1][2] | ||

| Trade names | Numerous | ||

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph | ||

| Pregnancy category |

| ||

| Routes of administration |

• By mouth (tablet) • Sublingual (tablet) • Intranasal (nasal spray) • Topical (gel, cream, patch, spray, emulsion) • Vaginal (tablet, cream, ring) • I.M. injection (oil solution) • S.C. injection (aq. soln.) • Subcutaneous implant | ||

| ATC code | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Pharmacokinetic data | |||

| Bioavailability | Oral: <5%[3] | ||

| Protein binding |

~98%:[3][4] • Albumin: 60% • SHBG: 38% • Free: 2% | ||

| Metabolism | Liver (via hydroxylation, sulfation, glucuronidation) | ||

| Metabolites |

Major (90%):[3] • Estrone • Estrone sulfate • Estrone glucuronide • Estradiol glucuronide | ||

| Biological half-life |

Oral: 13–20 hours[3] Sublingual: 8–18 hours[5] Topical (gel): 36.5 hours[6] | ||

| Excretion |

Urine: 54%[3] Feces: 6%[3] | ||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

| Synonyms | 17β-Estradiol; Estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17β-diol | ||

| CAS Number | |||

| PubChem CID | |||

| IUPHAR/BPS | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| UNII | |||

| KEGG | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| Chemical and physical data | |||

| Formula | C18H24O2 | ||

| Molar mass | 272.38 g/mol | ||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

| |||

| |||

| (verify) | |||

Estradiol, also spelled oestradiol, is a medication and naturally occurring steroid hormone.[7] It is an estrogen and is used mainly in hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for menopause,[7] hypogonadism, and transgender women. It is also used in hormonal contraception and sometimes in the treatment of hormone-sensitive cancers like prostate cancer. Estradiol can be taken by mouth, as a gel or patch that is applied to the skin, in through the vagina, by injection into muscle, or through the use of an implant that is placed into fat, among other routes.[7]

Side effects of estradiol in women include breast tenderness and enlargement, headache, fluid retention, and nausea. Men and children who are exposed to estradiol may develop symptoms of feminization, such as breast development, and men may also experience hypogonadism and infertility. It may increase the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer in women with an intact uterus if it is not taken together with a progestogen like progesterone. Estradiol should not be used in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding or who have breast cancer.

Estradiol was first isolated in 1935.[8] It first became available as a medication, in the form of estradiol benzoate, a prodrug of estradiol, in 1936.[9] Micronized estradiol, which allowed estradiol to be taken by mouth, was not introduced until 1975.[10] Estradiol is also used as other prodrugs like estradiol valerate and estradiol acetate.[7] Related estrogens such as ethinylestradiol, which is the most common estrogen in oral contraceptives, and conjugated equine estrogens (marketed as Premarin), are used as medications as well.

Medical uses

Hormone replacement therapy

Menopause

Estradiol is used in hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to treat moderate to severe menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, vaginal dryness and atrophy, and osteoporosis (bone loss). As unopposed estrogen therapy increases the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer, estradiol is usually combined with a progestogen like progesterone or medroxyprogesterone acetate in women with an intact uterus to prevent the effects of estradiol on the endometrium.[11]

Hypogonadism

Estrogen is responsible for the mediation of puberty in females, and in girls with delayed puberty due to hypogonadism such as in Turner syndrome, estradiol is used to induce the development of and maintain female secondary sexual characteristics such as breasts, wide hips, and a female fat distribution.

Transgender women

Estradiol is used as part of hormone replacement therapy for transgender women. The drug is used in higher dosages prior to sex reassignment surgery or orchiectomy to help suppress testosterone levels; after this procedure, estradiol continues to be used at lower dosages to maintain estradiol levels in the normal pre-menopausal female range.[12]

Birth control

Although almost all combined oral contraceptives contain the synthetic estrogen ethinylestradiol,[13] natural estradiol itself is also used in some hormonal contraceptives, including in estradiol-containing oral contraceptives and combined injectable contraceptives. It is formulated in combination with a progestin such as dienogest, nomegestrol acetate, or medroxyprogesterone acetate, and is often used in the form of an ester prodrug like estradiol valerate or estradiol cypionate. Hormonal contraceptives contain a progestin and/or estrogen and prevent ovulation and thus the possibility of pregnancy by suppressing the secretion of the gonadotropins follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), the peak of which around the middle of the menstrual cycle causes ovulation to occur.[14]

Prostate cancer

Although infrequently used in modern times and although synthetic estrogens like diethylstilbestrol and ethinylestradiol have been more commonly used, estradiol is used in the treatment of prostate cancer and is similarly effective to other therapies such as androgen deprivation therapy with castration and antiandrogens.[15][16][17] It is used in the form of the long-lasting injected estradiol prodrugs polyestradiol phosphate and estradiol undecylate,[15][16][18] and has also more recently been assessed in the form of transdermal estradiol patches.[16][19] Estrogens are effective in the treatment of prostate cancer by suppressing testosterone levels into the castrate range, increasing levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and thereby decreasing the fraction of free testosterone, and possibly also via direct cytotoxic effects on prostate cancer cells.[20][21][22] Parenteral estradiol is largely free of the cardiovascular side effects of the high oral dosages of synthetic estrogens that were used previously.[16][23][24] In addition, estrogens may have advantages relative to castration in terms of hot flashes, sexual interest and function, osteoporosis, and cognitive function and may offer significant benefits in terms of quality of life.[16][24][21][25] However, side effects such as gynecomastia and feminization in general may be difficult to tolerate or unacceptable for many men.[16]

Other uses

Breast cancer

Estrogens are effective in the treatment of about 35% of cases of breast cancer and have comparable effectiveness to antiestrogens like the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) tamoxifen.[26][27] Although estrogens are rarely used in the treatment of breast cancer in modern times and synthetic estrogens like diethylstilbestrol and ethinylestradiol have most commonly been used similarly to the case of prostate cancer, estradiol itself has been used in the treatment of breast cancer as well.[28]

Infertility

Estrogens may be used in treatment of infertility in women when there is a need to develop sperm-friendly cervical mucous or an appropriate uterine lining.[29][30]

Lactation suppression

Estrogens can be used to suppress and cease lactation and breast engorgement in postpartum women who do not wish to breastfeed.[31][26] They do this by directly decreasing the sensitivity of the alveoli of the mammary glands to the lactogenic hormone prolactin.[26]

Tall stature

Estrogens have been used to limit final height in adolescent girls with tall stature.[32] They do this by inducing epiphyseal closure and suppressing growth hormone-induced hepatic production and by extension circulating levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), a hormone that causes the body to grow and increase in size.[32] Although ethinylestradiol and conjugated equine estrogens have mainly been used for this purpose, estradiol can also be employed.[33][34]

Contraindications

Estradiol should be avoided when there is undiagnosed abnormal vaginal bleeding, known, suspected or a history of breast cancer, current treatment for metastatic disease, known or suspected estrogen-dependent neoplasia, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism or history of these conditions, active or recent arterial thromboembolic disease such as stroke, myocardial infarction, liver dysfunction or disease. Estradiol should not be taken by people with a hypersensitivity/allergy or those who are pregnant or are suspected pregnant.[35]

Adverse effects

The most common side effects of estradiol in women include breast tenderness, breast enlargement, headache, fluid retention, and nausea.[3]

An extensive list of possible side effects which may occur as a result of use of estradiol or have been associated with estrogen and/or progestogen therapy include:[35][36]

- Gynecological: changes in vaginal bleeding, dysmenorrhea, increase in size of uterine leiomyomata, vaginitis including vaginal candidiasis, changes in cervical secretion and cervical ectropion, ovarian cancer, endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer, nipple discharge, galactorrhea, fibrocystic breast changes and breast cancer.

- Cardiovascular: chest pain, deep and superficial venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, thrombophlebitis, myocardial infarction, stroke, and increased blood pressure.

- Gastrointestinal: nausea and vomiting, abdominal cramps, bloating, diarrhea, dyspepsia, dysuria, gastritis, cholestatic jaundice, increased incidence of gallbladder disease, pancreatitis, or enlargement of hepatic hemangiomas.

- Cutaneous: chloasma or melasma (which may continue despite discontinuation of the drug), erythema multiforme, erythema nodosum, otitis media, hemorrhagic eruption, loss of scalp hair, pruritus, or rash.

- Ocular: retinal vascular thrombosis, steepening of corneal curvature or intolerance to contact lenses.

- Central: headache, migraine, dizziness, chorea, nervousness/anxiety, mood disturbances, irritability, changes in libido, worsening of epilepsy, and increased risk of dementia.

- Others: changes in weight, reduced carbohydrate tolerance, worsening of porphyria, edema, arthralgias, bronchitis, leg cramps, hemorrhoids, urticaria, angioedema, anaphylactic reactions, syncope, toothache, tooth disorder, urinary incontinence, hypocalcemia, exacerbation of asthma, and increased triglycerides.

Estrogens should only be used for the shortest possible time and at the lowest effective dose due to these risks. Attempts to gradually reduce the medication via a dose taper should be made every three to six months.[35]

Interactions

Inducers of cytochrome P450 enzymes like CYP3A4 such as St. John's wort, phenobarbital, carbamazepine and rifampicin decrease the circulating levels of estradiol by accelerating its metabolism, whereas inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes like CYP3A4 such as erythromycin, cimetidine,[37] clarithromycin, ketoconazole, itraconazole, ritonavir and grapefruit juice may slow its metabolism resulting in increased levels of estradiol in the circulation.[35]

Pharmacology

Estradiol is an estrogen, or an agonist of the nuclear estrogen receptors (ERs), ERα and ERβ.[7] It is also an agonist of the membrane estrogen receptors (mERs) such as the GPER, Gq-mER, ER-X, and ERx.[38][39] Estradiol is far more potent as an estrogen than other natural estrogens like estrone and estriol.[7]

Effects in the body and brain

The ERs are expressed widely throughout the body, including in the breasts, uterus, vagina, prostate gland, fat, skin, bone, liver, pituitary gland, hypothalamus, and elsewhere throughout the brain.[8] Through activation of the ERs (as well as the mERs), estradiol has many effects, including the following:

- Promotes growth, function, and maintenance of the breasts, uterus, and vagina during puberty and thereafter[8][40]

- Mediates deposition of subcutaneous fat in a feminine pattern, especially in the breasts, hips, buttocks, and thighs[41]

- Maintains skin health, integrity, appearance, and hydration and slows the rate of aging of the skin[42]

- Produces the growth spurt, widening of the hips (in females), and epiphyseal closure during puberty and maintains bone mineral density throughout life[43][44]

- Modulates hepatic protein synthesis, such as the production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and many other proteins, with consequent effects on the cardiovascular system and various other systems[15]

- Exerts negative feedback on the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis by suppressing the secretion of the gonadotropins FSH and LH from the pituitary gland, thereby inhibiting gonadal sex hormone production as well as ovulation and fertility[45][15][20]

- Regulates the vasomotor system and body temperature via the hypothalamus, thereby preventing hot flashes[46][47]

- Modulates brain function, with effects on mood, emotionality, and sexuality, as well as cognition and memory[48]

- Influences the risk and/or progression of hormone-sensitive cancers including breast cancer, prostate cancer, and endometrial cancer[49][15]

Effects on oxytocin signaling

Estrogen has been found to increase the secretion of oxytocin and to increase the expression of its receptor, the oxytocin receptor, in the brain.[50] In women, a single dose of estradiol has been found to be sufficient to increase circulating oxytocin concentrations.[51]

Differences from other estrogens

Synthetic estrogens ethinylestradiol and diethylstilbestrol and the natural conjugated equine estrogens have disproportionate effects on hepatic protein synthesis relative to effects in other tissues, whereas this is not the case with estradiol (see table below).[7] In the case of ethinylestradiol, substitution with an ethynyl group at the C17α position results in steric hindrance and prevents tissue-selective inactivation of this estrogen in the liver, resulting in pronouncedly disproportionate effects in the liver compared to other tissues.[52][53][48][54][55] Because of this, there is a considerably higher risk of cardiovascular side effects like venous thromboembolism with ethinylestradiol (as well as with diethylstilbestrol) compared to estradiol.[55][23]

In addition to the liver, ethinylestradiol shows disproportionate estrogenic effects in the uterus due to loss of tissue-selective inactivation by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD).[48][54] This is associated with a significantly lower incidence of vaginal bleeding and spotting, particularly in combination with progestogens (which induce 17β-HSD expression in the uterus),[7] and is an important contributing factor in why ethinylestradiol, in spite of its inferior safety profile, has been widely used in oral contraceptives instead of estradiol.[56][55]

| Estrogen | Hot flashes | FSH | HDL cholesterol | SHBG | CBG | Angiotensinogen | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Estriol | 30 | 30 | 20 | ? | ? | ? | |||

| Estrone sulfate | ? | 90 | 50 | 90 | 70 | 150 | |||

| CEEs | 120 | 110 | 150 | 300 | 150 | 500 | |||

| Equilin sulfate | ? | ? | 600 | 750 | 600 | 750 | |||

| Ethinylestradiol | 12,000 | 12,000 | 40,000 | 50,000 | 60,000 | 35,000 | |||

| Diethylstilbestrol | ? | 340 | ? | 2,560 | 2,450 | 1,950 | |||

| Hot flashes = clinical relief of hot flashes; FSH = suppression of FSH levels; HDL cholesterol, SHBG, CBG, and angiotensinogen = increase in the serum levels of these hepatic proteins. | |||||||||

Pharmacokinetics

| Estrone:Estradiol Ratio[7] | |

|---|---|

| Premenopause | 1:2 |

| Postmenopause | 2:1 |

| Oral estradiol | 5:1 |

| Oral estrone sulfate | 5:1 |

| Transdermal estradiol (patch) | 1:1 |

| Transdermal estradiol (gel) | 1:1 |

| Intranasal estradiol | 2:1 |

| Sublingual estradiol | 1:3 |

| Vaginal estradiol | 1:5 |

| Subcutaneous estradiol (implant) | 1:1.5 |

| Intramuscular estradiol | 1:2 |

Estrogen is marketed in a number of ways to address issues of hypoestrogenism. Thus, there are oral, transdermal, topical, vaginal, intranasal, injectable, and implantable preparations. Furthermore, the estradiol molecule may be linked to an alkyl group at the C17β (and/or C3) position to improve bioavailability and/or duration. Such modifications give rise to forms such as estradiol acetate (oral and vaginal applications) and to estradiol valerate (injectable), which behave as prodrugs of estradiol.

Different routes of administration of estradiol produce different effects in the body due to differences in the amount of estradiol that is exposed to the intestines and liver as well as different levels of estradiol produced.[57] Oral preparations are not necessarily predictably absorbed, and are subject to a first-pass through the liver, where they can be metabolized, and also initiate unwanted side effects. Therefore, alternative routes of administration that bypass the liver before primary target organs are hit have also been developed. Parenteral routes including transdermal, vaginal, sublingual, intranasal, intramuscular, and subcutaneous are not subject to the initial liver passage.

Distribution

Estradiol is plasma protein bound loosely to albumin and tightly to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), with approximately 97 to 98% of estradiol bound to plasma proteins.[58] In the circulation, approximately 38% of estradiol is bound to SHBG and 60% is bound to albumin, with 2 to 3% free.[59] However, with oral estradiol, there is an increase in hepatic SHBG production and hence SHBG levels, and this results in a reduced fraction of free estradiol.[3]

Metabolism

There are several major pathways of estradiol metabolism, which occur both in the liver and in other tissues:[15][7][3]

- Dehydrogenation by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD) into estrone

- Conjugation by estrogen sulfotransferases and UDP-glucuronyltransferases into C3 and/or C17β estrogen conjugates like estrone sulfate and estradiol glucuronide

- Hydroxylation by cytochrome P450 enzymes such as CYP1A1 and CYP3A4 into catechol estrogens like 2-hydroxyestrone and 2-hydroxyestradiol as well as 16-hydroxylated estrogens like 16α-hydroxyestrone and estriol (16α-hydroxyestradiol)

Both dehydrogenation of estradiol by 17β-HSD into estrone and conjugation into estrogen conjugates are reversible transformations.[15][7]

Estradiol can also be reversibly converted into long-lived lipoidal estradiol forms like estradiol palmitate and estradiol stearate as a minor route of metabolism.[60]

The terminal half-life of estradiol administered via intravenous injection is 2 hours in men and 50 minutes in women.[61] Other routes of administration of estradiol like oral ingestion or intramuscular injection have far longer terminal half-lives and durations of action due to (1) the formation of a large circulating reservoir of metabolically resistant estrogen conjugates that can be reconverted back into estradiol and/or (2) the formation of slowly-releasing depots.[15][7]

Elimination

A single dose of oral estradiol valerate is eliminated 54% in urine and 6% in feces.[3] A substantial amount of estradiol is also excreted in bile.[3] The urinary metabolites of estradiol are predominantly present in the form of estrogen conjugates, including glucuronides and, to a lesser extent, sulfates.[3] The main metabolites of estradiol in urine are estrone glucuronide (13–30%), 2-hydroxyestrone (2.6–10.1%), unchanged estradiol (5.2–7.5%), estriol (2.0–5.9%), and 16α-hydroxyestrone (1.0–2.9%).[3]

Oral administration

Absorption

The oral bioavailability of estradiol in its usual state is very poor and the hormone must be either micronized or esterified (as in, e.g., estradiol valerate or estradiol acetate) to be bioavailable to any significant extent.[58][62][63] This is because estradiol is extensively metabolized during first-pass metabolism in the intestines and liver, and micronization increases the rate of absorption and improves the metabolic stability of estradiol.[59] As micronization is required for significant bioavailability, all oral estradiol tablets are micronized.[62] Estradiol is rapidly and completely absorbed upon oral administration.[59] This is true for oral doses of 2 mg and 4 mg, but absorption was found to be incomplete for a dose of 8 mg.[59] Although micronized estradiol is well-absorbed orally and has greatly improved bioavailability relative to non-micronized estradiol, its bioavailability is still nonetheless very low due to the extensive first-pass metabolism.[58][62] Around 95% of oral estradiol is metabolized prior to entering systemic circulation,[59] and in accordance, the absolute bioavailability of oral micronized estradiol is between 0.1% and 12%.[58]

A dosage of 1 mg/day oral micronized estradiol results in circulating concentrations of 30–50 pg/mL estradiol and 150–300 pg/mL estrone, while a dosage of 2 mg/day produces circulating levels of 50–180 pg/mL estradiol and 300–850 pg/mL estrone.[48]

Metabolism

When taken orally, most estradiol is converted into estrone and estrone sulfate in the liver during first-pass metabolism.[64][65] Oral estradiol administration produces a plasma estradiol-to-estrone ratio of about 1:5 to 1:7.[66]

About 15% of orally administered estradiol is converted into estrone and 65% is converted into estrone sulfate.[15] About 5% of estrone and 1.4% of estrone can be converted back into estradiol.[15] An additional 21% of estrone sulfate can be converted into estrone, whereas the conversion of estrone to estrone sulfate is approximately 54%.[15] This reversible interconversion between estradiol and estrone is mediated by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase,[15] whereas the interconversion between estrone and estrone sulfate is mediated by estrogen sulfotransferase and steroid sulfatase.[67][68]

The terminal half-life of orally administered estradiol is a composite parameter that is dependent on interconversion between estrone and sulfate and glucuronide conjugates and enterohepatic recirculation.[15] It has a range of 13 to 20 hours.[15]

Pharmacodynamics

Estrone is approximately 10-fold less potent relative to estradiol as an estrogen,[69] and also has a different binding profile relative to estradiol, for instance, lacking affinity to the GPER.[70] In addition, the resulting supraphysiological levels of estrogen in the liver (4- to 5-fold higher relative to the circulation)[71] increase the risk of blood clots,[72] suppress growth hormone (GH)-mediated insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) production,[73][74] and increase levels of a variety of binding proteins including thyroid binding globulin (TBG), cortisol binding globulin (CBG), sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), growth hormone binding protein (GHBP),[75] insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins (IGFBPs),[76] and copper binding protein (CBP),[64][77] but also produce positive blood lipid changes.[65][78]

Other routes of administration

Sublingual administration

Micronized estradiol tablets can be taken sublingually instead of orally.[79] All estradiol tablets are micronized, as estradiol cannot be absorbed efficiently otherwise.[62] Sublingual ingestion bypasses first-pass metabolism in the intestines and liver.[80] It has been found to result in levels of estradiol and an estradiol-to-estrone ratio that are substantially higher in comparison to oral ingestion.[81] Circulating levels of estradiol are as much as 10-fold higher with sublingual administration relative to oral administration and the absolute bioavailability of estradiol is approximately 5-fold higher.[7] On the other hand, levels of estradiol fall rapidly with sublingual administration, whereas they remain elevated for an extended period of time with oral administration.[7][15] This is responsible for the divergence between the maximal estradiol levels achieved and the absolute bioavailability.[7][15]

The rapid and steep fall in estradiol levels with sublingual administration is analogous to the case of intravenous administration of the hormone, in which there is a rapid distribution phase of 6 minutes and terminal disposition phase of only 1 to 2 hours.[7][15][61] In contrast to intravenous and sublingual administration, the terminal half-life of estradiol is 13 to 20 hours with oral administration.[7][15] The difference is due to the fact that, upon oral administration, a large hormonally inert pool of estrogen sulfate and glucuronide conjugates with extended terminal half-lives is reversibly formed from estradiol during first-pass metabolism, and this pool serves as a metabolically resistant and long-lasting circulating reservoir for slow reconversion back into estradiol.[7][15]

Upon sublingual ingestion, a single 0.25 mg tablet of micronized estradiol has been found to produce peak levels of 300 pg/mL estradiol and 60 pg/mL estrone within 1 hour.[7] A higher dose of 1 mg estradiol was found to result in maximum levels of 450 pg/mL estradiol and 165 pg/mL estrone.[7] This was followed by a rapid decline in estradiol levels to 85 pg/mL within 3 hours, whereas the decline in estrone levels was much slower and reached a level of 80 pg/mL after 18 hours.[7]

Although sublingual administration of estradiol has a relatively short duration, the drug can be administered multiple times per day in divided doses to compensate for this.[7] In addition, it is notable that the magnitude of the genomic effects of estradiol (i.e., signaling through the nuclear ERs) appears to be dependent solely on the total exposure as opposed to the duration of exposure.[7] For instance, in both normal human epithelial breast cells and ER-positive breast cancer cells, the rate of breast cell proliferation has been found not to differ with estradiol incubation of 1 nM for 24 hours and incubation of 24 nM for 1 hour.[7] In other words, short-term high concentrations and long-term low concentrations of estradiol appear to have the same degree of effect in terms of genomic estrogenic signaling.[7]

On the other hand, non-genomic actions of estradiol, such as signaling through membrane estrogen receptors like the GPER, may be reduced with short-term high concentrations of estradiol relative to more sustained levels.[7] For instance, although daily intranasal administration of estradiol (which, similarly to sublingual administration, produces extremely high peak levels of estradiol followed by a rapid fall in estradiol levels) is associated in postmenopausal women with comparable clinical effectiveness (e.g., for hot flashes) relative to longer acting routes of estradiol administration, it is also associated with significantly lower rates of breast tension (tenderness and enlargement) relative to longer acting estradiol routes, and this is thought to reflect comparatively diminished non-genomic signaling.[7]

Intranasal administration

Estradiol is or was available as a nasal spray (brand name Aerodiol) in some countries.[82][83][84][85] The Aerodiol product was discontinued in 2007.[86][87]

Transdermal administration

Transdermal estradiol is available in the forms of topical gels, patches, sprays, and emulsions.

Estradiol patches delivering a daily dosage of 0.05 mg (50 µg) achieve estradiol and estrone levels of 30–65 pg/mL and 40–45 pg/mL, respectively, while a daily dosage of 0.1 mg (100 µg) attains respective levels of 50–90 pg/mL and 30–65 pg/mL of estradiol and estrone.[48]

Once daily application of 1.25 g topical gel containing 0.75 mg estradiol (brand name EstroGel) for 2 weeks was found to produce mean peak estradiol and estrone levels of 46.4 pg/mL and 64.2 pg/mL, respectively.[88] The time-averaged levels of circulating estradiol and estrone with this formulation over the 24-hour dose interval were 28.3 pg/mL and 48.6 pg/mL, respectively.[88] Levels of estradiol and estrone are stable and change relatively little over the course of the 24 hours following an application, indicating a long duration of action of this route.[88] Steady-state levels of estradiol are achieved after three days of applications.[88] A higher dosage of topical estradiol gel containing 1.5 mg estradiol per daily application has been found to produce estradiol levels of 40–100 pg/mL and estrone levels of 90 pg/mL, while 3 mg/daily has been found to result in respective estradiol and estrone levels of 60–140 pg/mL and 45–155 pg/mL.[48]

Transdermal estradiol bypasses the intestines and liver and hence first-pass metabolism. Estradiol patches have been found not to increase the risk of blood clots[72] and to not affect hepatic IGF-1, SHBG, GHBP,[75] IGFBP,[76] or other protein production.[73][74][77] Transdermal administration of estradiol via patch or gel results in a ratio of about 1:1.[15]

Vaginal administration

Vaginal micronized estradiol achieves a far higher estradiol-to-estrone ratio in comparison to oral estradiol, with a daily dosage of 0.5 mg resulting in estradiol and estrone levels of 250 pg/mL and 130 pg/mL, respectively.[48] Vaginal micronized estradiol bypasses the intestines and liver and first-pass metabolism similarly to transdermal estradiol and in accordance does not affect hepatic protein production at menopausal replacement dosages.[89]

Intramuscular injection

| Ester | Peak levels | Time to peak | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol cypionate | E2: 338 pg/mL E1: 145 pg/mL | E2: 3.9 days E1: 5.1 days | 11 days |

| Estradiol valerate | E2: 667 pg/mL E1: 324 pg/mL | E2: 2.2 days E1: 2.7 days | 7–8 days |

| Estradiol benzoate | E2: 940 pg/mL E1: 343 pg/mL | E2: 1.8 days E1: 2.4 days | 4–5 days |

Estradiol, in an ester prodrug form such as estradiol valerate or estradiol cypionate, can be administered by intramuscular injection, via which a long-lasting depot effect occurs.[90][91] In contrast to the oral route, the bioavailability of estradiol and its esters like estradiol valerate is complete (i.e., 100%) with intramuscular injection.[61]

A single 4 mg intramuscular injection of estradiol cypionate or estradiol valerate has been found to result in maximal plasma levels of estradiol of about 250 pg/mL and 390 pg/mL, respectively, with levels declining to 100 pg/mL (the baseline for estradiol cypionate) by 12–14 days.[92][93] A single 2.5 mg intramuscular injection of estradiol benzoate in patients being administered a GnRH analogue (and hence having minimal baseline levels of estrogen) was found to result in serum estradiol levels of >400 pg/mL at 24 hours post-administration.[90] The differences in the serum levels of estradiol achieved with these different estradiol esters may be explained by their different rates of absorption, as their durations and levels attained appear to be inversely proportional. For instance, estradiol benzoate, which has the shortest duration (4–5 days with a single intramuscular injection of 5 mg), produces the highest levels of estradiol, while estradiol cypionate, which has the longest duration (~11 days with 5 mg), produces the lowest levels of estradiol.[90] Estradiol valerate was found to have a duration of 7–8 days after a single intramuscular injection of 5 mg.[90]

A study of combined high-dose i.m. estradiol valerate and hydroxyprogesterone caproate in peri- and postmenopausal and hypogonadal women (described as a "pseudopregnancy" regimen), with specific dosages of 40 mg weekly and 250 mg weekly, respectively, was found to result in serum estradiol levels of 3028–3226 pg/mL after three months and 2491–2552 pg/mL after six months of treatment from a baseline of 27.8–34.8 pg/mL.[94]

Subcutaneous injection

Subcutaneous and intramuscular injections of estradiol cypionate in an aqueous suspension have been found to show almost identical estradiol levels produced and pharmacokinetics (e.g., duration).[91] However, subcutaneous injections may be easier and less painful to perform compared to intramuscular injections, and hence, may result in improved patient compliance and satisfaction.[91]

Subcutaneous implant

Estradiol can be given in the form of a long-lasting subcutaneous implant (or "pellet").[7]

Normal estradiol levels

For comparative purposes, normal menstrual cycle serum levels of estradiol in premenopausal women are 40 pg/mL in the early follicular phase to 250 pg/mL at the middle of the cycle and 100 pg/mL during the mid-luteal phase.[48] Serum estrone levels during the menstrual cycle range from 40 to 170 pg/mL, which parallels the serum levels of estradiol.[48] Mean levels of estradiol in premenopausal women are between 80 and 150 pg/mL according to different sources.[92][95][96] The estradiol-to-estrone ratio in premenopausal women is higher than 1:1.[48] In postmenopausal women, the serum levels of estradiol are below 15 pg/ml and the average levels of estrone are about 30 pg/ml; the estradiol-to-estrone ratio is reversed to less than 1:1.[48]

Chemistry

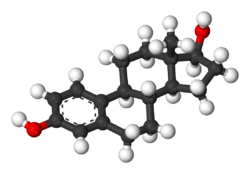

Estradiol is an estrane (C18) steroid.[7] It is also known as 17β-estradiol (to distinguish it from 17α-estradiol) or as estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17β-diol. It has two hydroxyl groups, one at the C3 position and the other at the 17β position, as well as three double bonds in the A ring. Due to its two hydroxyl groups, estradiol is often abbreviated as E2. The structurally related estrogens, estrone (E1), estriol (E3), and estetrol (E4) have one, three, and four hydroxyl groups, respectively.

Hemihydrate

A hemihydrate form of estradiol, estradiol hemihydrate, is widely used medically under a large number of brand names similarly to estradiol.[97] In terms of activity and bioequivalence, estradiol and its hemihydrate are identical, with the only disparities being an approximate 1% difference in potency by weight (due to the presence of water molecules in the hemihydrate form of the substance) and a slower rate of release with certain formulations of the hemihydrate.[98][99] This is because estradiol hemihydrate is more hydrated than anhydrous estradiol, and for this reason, is more insoluble in water in comparison, which results in slower absorption rates with specific formulations of the drug such as vaginal tablets.[99] Estradiol hemihydrate has also been shown to result in less systemic absorption as a vaginal tablet formulation relative to other topical estradiol formulations such as vaginal creams.[64]

Derivatives

A variety of C17β and/or C3 ester prodrugs of estradiol, such as estradiol acetate, estradiol benzoate, estradiol cypionate, estradiol dipropionate, estradiol enanthate, estradiol undecylate, estradiol valerate, and polyestradiol phosphate (an estradiol ester in polymeric form), among many others, have been developed and introduced for medical use as estrogens. Estramustine phosphate is also an estradiol ester, but with a nitrogen mustard moiety attached, and is used as an alkylating antineoplastic agent in the treatment of prostate cancer. Cloxestradiol acetate and promestriene are ether prodrugs of estradiol that have been introduced for medical use as estrogens as well, although they are little known and rarely used.

Synthetic derivatives of estradiol used as estrogens include ethinylestradiol, ethinylestradiol sulfonate, mestranol, methylestradiol, moxestrol, and quinestrol, all of which are 17α-substituted estradiol derivatives. Synthetic derivatives of estradiol used in scientific research include 8β-VE2 and 16α-LE2.

History

Estradiol was first isolated in 1935.[8] It was also originally known as dihydroxyestrin or alpha-estradiol.[100][101] It was first marketed, as estradiol benzoate, in 1936.[9] Estradiol was also marketed in the 1930s under brand names such as Progynon-DH, Ovocylin, and Dimenformon.[100][101] Micronized estradiol, via the oral route, was first evaluated in 1972,[102] and this was followed by the evaluation of vaginal and intranasal micronized estradiol in 1977.[103] Oral micronized estradiol was first approved in the United States under the brand name Estrace in 1975.[10]

Society and culture

Generic name

Estradiol is the generic name of estradiol in American English and its INN, USAN, USP,[104] BAN, DCF, and JAN.[105][97][106][107] It is pronounced /ˌɛstrəˈdaɪoʊl/ ES-trə-DYE-ohl.[1][2] Estradiolo is the name of estradiol in Italian and the DCIT[105] and estradiolum is its name in Latin, whereas its name remains unchanged as estradiol in Spanish, Portuguese, French, and German.[105][97] Oestradiol, in which the "O" is silent, was the former BAN of estradiol and its name in British English,[107] but the spelling was eventually changed to estradiol.[105]

When estradiol is provided in its hemihydrate form, its INN is estradiol hemihydrate.[97]

Brand names

Estradiol is marketed under a large number of brand names throughout the world.[97][105] Examples of major brand names in which estradiol has been marketed in include Climara, Climen, Dermestril, Divigel, Estrace, Natifa, Estraderm, Estraderm TTS, Estradot, Estreva, Estrimax, Estring, Estrofem, Estrogel, Evorel, Fem7 (or FemSeven), Menorest, Oesclim, Oestrogel, Sandrena, Systen, and Vagifem.[97][105] Estradiol valerate is marketed mainly as Progynova and Progynon-Depot, while it is marketed as Delestrogen in the U.S.[97][108] Estradiol cypionate is used mainly in the U.S. and is marketed under the brand name Depo-Estradiol.[97][108] Estradiol acetate is available as Femtrace, Femring, and Menoring.[108]

Estradiol is also widely available in combination with progestogens.[105] It is available in combination with norethisterone acetate under the major brand names Activelle, Cliane, Estalis, Eviana, Evorel Conti, Evorel Sequi, Kliogest, Novofem, Sequidot, and Trisequens; with drospirenone as Angeliq; with dydrogesterone as Femoston, Femoston Conti; and with nomegestrol acetate as Zoely.[105] Estradiol valerate is available with cyproterone acetate as Climen; with dienogest as Climodien and Qlaira; with norgestrel as Cyclo-Progynova and Progyluton; with levonorgestrel as Klimonorm; with medroxyprogesterone acetate as Divina and Indivina; and with norethisterone enanthate as Mesigyna and Mesygest.[105] Estradiol cypionate is available with medroxyprogesterone acetate as Cyclo-Provera, Cyclofem, Feminena, Lunelle, and Novafem;[109] estradiol enanthate with algestone acetophenide as Deladroxate, Nomagest, and Novular and with algestone acetonide as Topasel and Yectames;[105][110][111] and estradiol benzoate is marketed with progesterone as Mestrolar and Nomestrol.[105]

Estradiol valerate is also widely available in combination with prasterone enanthate (DHEA enanthate) under the brand name Gynodian Depot.[105]

List of formulations

- Oral tablets: estradiol (Estrace, Estrofem), estradiol acetate (Femtrace), estradiol valerate (Progynova)

- Transdermal patches (Alora, Climara, Minivelle, Vivelle-Dot, Menostar, Estraderm)

- Topical gels (Estrogel, Estrasorb, Estraderm, Rontagel), sprays (Evamist, Lenzetto), and ointments (Divigel, Estrasorb Topical, Elestrin)

- Nasal sprays: Aerodiol

- Vaginal ointments (Estrace Vaginal Cream), rings (Estring, Femring (as estradiol acetate)) and tablets (Vagifem)

- Injectables: estradiol valerate (Progynon Depot, Delestrogen), estradiol cypionate (Depo-Estradiol), estradiol undecylate (Progynon Depot 100), polyestradiol phosphate (Estradurin)

- Combined with a progestogen: CombiPatch (transdermal), Activella (oral), AngeliQ (oral)

Availability

United States

As of November 2016, estradiol is available in the United States in the following forms:[108]

- Oral tablets (Femtrace (as estradiol acetate), Gynodiol, Innofem, generics)

- Transdermal patches (Alora, Climara, Esclim, Estraderm, Fempatch, Menostar, Minivelle, Vivelle, Vivelle-Dot, generics)

- Topical gels (Divigel, Elestrin, Estrogel), sprays (Evamist), and emulsions (Estrasorb)

- Vaginal tablets (Vagifem, generics), creams (Estrace), and rings (Estrace, Femring (as estradiol acetate))

- Oil solution for intramuscular injection (Delestrogen (as estradiol valerate), Depo-Estradiol (as estradiol cypionate))

Oral estradiol valerate (Progynova) and other esters of estradiol that are used intramuscularly like estradiol benzoate, estradiol enanthate, and estradiol undecylate all are not marketed in the U.S.[108] Polyestradiol phosphate (Estradurin) was marketed in the U.S. previously but is no longer available.[108]

Estradiol is also available in the U.S. in combination with progestogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms:[108]

- Oral tablets with drospirenone (Angeliq) and norethisterone acetate (Activella, Amabelz)

- Transdermal patches with levonorgestrel (Climara Pro) and norethisterone acetate (Combipatch)

And for use as a combined hormonal contraceptive:[108]

- Oral tablets as estradiol valerate with dienogest (Natazia)

Estradiol was also previously available in oral tablet form in combination with norgestimate (Prefest), but this product is no longer available.[108] A combination formulation of estradiol and progesterone micronized in oil-filled oral capsules (TX-001HR) is currently under development in the U.S. for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and endometrial hyperplasia but has yet to be approved or marketed.[112][113] Estradiol was formerly available as estradiol cypionate in combination with medroxyprogesterone acetate as a once-monthly intramuscular combined injectable contraceptive (Lunelle), but this product was discontinued.[108] A combination of estradiol cypionate and testosterone cypionate (Depo-Testadiol) and a combination of estradiol valerate and testosterone enanthate (Ditate-DS) were previously marketed in the U.S. but have been discontinued as well.[108]

Estradiol and estradiol esters are also available in custom preparations from compounding pharmacies in the U.S.[114] This includes subcutaneous pellet implants.[115] In addition, topical creams that contain estradiol are generally regulated as cosmetics rather than as drugs in the U.S. and hence are also sold over-the-counter and may be purchased without a prescription on the Internet.[116]

Other countries

Estradiol and/or its esters are widely available in countries throughout the world in a variety of formulations. For an extensive list of countries that they are marketed in along with the associated brand names, see here.

See also

References

- 1 2 Susan M. Ford; Sally S. Roach (7 October 2013). Roach's Introductory Clinical Pharmacology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 525–. ISBN 978-1-4698-3214-2.

- 1 2 Maryanne Hochadel; Mosby (1 April 2015). Mosby's Drug Reference for Health Professions. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 602–. ISBN 978-0-323-31103-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Stanczyk, Frank Z.; Archer, David F.; Bhavnani, Bhagu R. (2013). "Ethinyl estradiol and 17β-estradiol in combined oral contraceptives: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and risk assessment". Contraception. 87 (6): 706–727. ISSN 0010-7824. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.12.011.

- ↑ Tommaso Falcone; William W. Hurd (2007). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 22–. ISBN 0-323-03309-1.

- ↑ Price, T; Blauer, K; Hansen, M; Stanczyk, F; Lobo, R; Bates, G (1997). "Single-dose pharmacokinetics of sublingual versus oral administration of micronized 17-estradiol". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 89 (3): 340–345. ISSN 0029-7844. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(96)00513-3.

- ↑ Naunton, Mark; Al Hadithy, Asmar F. Y.; Brouwers, Jacobus R. B. J.; Archer, David F. (2006). "Estradiol gel". Menopause. 13 (3): 517–527. ISSN 1072-3714. doi:10.1097/01.gme.0000191881.52175.8c.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration" (PDF). Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. PMID 16112947. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875.

- 1 2 3 4 Fritz F. Parl (2000). Estrogens, Estrogen Receptor and Breast Cancer. IOS Press. pp. 4,111. ISBN 978-0-9673355-4-4.

- 1 2 Enrique Raviña; Hugo Kubinyi (16 May 2011). The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. John Wiley & Sons. p. 175. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- 1 2 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Set_Current_Drug&ApplNo=084499&DrugName=ESTRACE&ActiveIngred=ESTRADIOL&SponsorApplicant=BRISTOL%20MYERS%20SQUIBB&ProductMktStatus=3&goto=Search.DrugDetails

- ↑ Mutschler, Ernst; Schäfer-Korting, Monika (2001). Arzneimittelwirkungen (in German) (8 ed.). Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. pp. 434, 444. ISBN 3-8047-1763-2.

- ↑ http://www.wpath.org/publications_standards.cfm

- ↑ Evans G, Sutton EL (May 2015). "Oral contraception". Med Clin North Am. 99 (3): 479–503. PMID 25841596. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.004.

- ↑ Glasier, Anna (2010). "Contraception". In Jameson, J. Larry; De Groot, Leslie J. Endocrinology (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. pp. 2417–2427. ISBN 978-1-4160-5583-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Michael Oettel; Ekkehard Schillinger (6 December 2012). Estrogens and Antiestrogens II: Pharmacology and Clinical Application of Estrogens and Antiestrogen. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 165–178, 235–237, 261–272, 538–542. ISBN 978-3-642-60107-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lycette JL, Bland LB, Garzotto M, Beer TM (2006). "Parenteral estrogens for prostate cancer: can a new route of administration overcome old toxicities?". Clin Genitourin Cancer. 5 (3): 198–205. PMID 17239273. doi:10.3816/CGC.2006.n.037.

- ↑ Cox RL, Crawford ED (1995). "Estrogens in the treatment of prostate cancer". J. Urol. 154 (6): 1991–8. PMID 7500443.

- ↑ Altwein, J. (1983). "Controversial Aspects of Hormone Manipulation in Prostatic Carcinoma": 305–316. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-4349-3_38.

- ↑ Ockrim JL; Lalani el-N; Kakkar AK; Abel PD (August 2005). "Transdermal estradiol therapy for prostate cancer reduces thrombophilic activation and protects against thromboembolism". J. Urol. 174 (2): 527–33; discussion 532–3. PMID 16006886. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000165567.99142.1f.

- 1 2 Waun Ki Hong; James F. Holland (2010). Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine 8. PMPH-USA. pp. 753–. ISBN 978-1-60795-014-1.

- 1 2 Scherr DS, Pitts WR (2003). "The nonsteroidal effects of diethylstilbestrol: the rationale for androgen deprivation therapy without estrogen deprivation in the treatment of prostate cancer". J. Urol. 170 (5): 1703–8. PMID 14532759. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000077558.48257.3d.

- ↑ Coss, Christopher C.; Jones, Amanda; Parke, Deanna N.; Narayanan, Ramesh; Barrett, Christina M.; Kearbey, Jeffrey D.; Veverka, Karen A.; Miller, Duane D.; Morton, Ronald A.; Steiner, Mitchell S.; Dalton, James T. (2012). "Preclinical Characterization of a Novel Diphenyl Benzamide Selective ERα Agonist for Hormone Therapy in Prostate Cancer". Endocrinology. 153 (3): 1070–1081. ISSN 0013-7227. PMID 22294742. doi:10.1210/en.2011-1608.

- 1 2 von Schoultz B, Carlström K, Collste L, Eriksson A, Henriksson P, Pousette A, Stege R (1989). "Estrogen therapy and liver function--metabolic effects of oral and parenteral administration". Prostate. 14 (4): 389–95. PMID 2664738.

- 1 2 Ockrim J, Lalani EN, Abel P (2006). "Therapy Insight: parenteral estrogen treatment for prostate cancer--a new dawn for an old therapy". Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 3 (10): 552–63. PMID 17019433. doi:10.1038/ncponc0602.

- ↑ Wibowo E, Schellhammer P, Wassersug RJ (2011). "Role of estrogen in normal male function: clinical implications for patients with prostate cancer on androgen deprivation therapy". J. Urol. 185 (1): 17–23. PMID 21074215. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.094.

- 1 2 3 John A. Thomas; Edward J. Keenan (6 December 2012). Principles of Endocrine Pharmacology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 148–. ISBN 978-1-4684-5036-1.

- ↑ William R. Miller; James N. Ingle (8 March 2002). Endocrine Therapy in Breast Cancer. CRC Press. pp. 49–52. ISBN 978-0-203-90983-6.

- ↑ Ellis, MJ; Dehdahti, F; Kommareddy, A; Jamalabadi-Majidi, S; Crowder, R; Jeffe, DB; Gao, F; Fleming, G; Silverman, P; Dickler, M; Carey, L; Marcom, PK (2014). "A randomized phase 2 trial of low dose (6 mg daily) versus high dose (30 mg daily) estradiol for patients with estrogen receptor positive aromatase inhibitor resistant advanced breast cancer.". Cancer Research. 69 (2 Supplement): 16. ISSN 0008-5472. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.SABCS-16.

- ↑ J. Aiman (6 December 2012). Infertility: Diagnosis and Management. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 133–134. ISBN 978-1-4613-8265-2.

- ↑ Glenn L. Schattman; Sandro Esteves; Ashok Agarwal (12 May 2015). Unexplained Infertility: Pathophysiology, Evaluation and Treatment. Springer. pp. 266–. ISBN 978-1-4939-2140-9.

- ↑ A. Labhart (6 December 2012). Clinical Endocrinology: Theory and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 696–. ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8.

- 1 2 Juul A (2001). "The effects of oestrogens on linear bone growth". Hum. Reprod. Update. 7 (3): 303–13. PMID 11392377.

- ↑ Albuquerque EV, Scalco RC, Jorge AA (2017). "Management of Endocrine Disease: Diagnostic and therapeutic approach of tall stature". Eur. J. Endocrinol. PMID 28274950. doi:10.1530/EJE-16-1054.

- ↑ Upners EN, Juul A (2016). "Evaluation and phenotypic characteristics of 293 Danish girls with tall stature: effects of oral administration of natural 17β-estradiol". Pediatr. Res. 80 (5): 693–701. PMID 27410906. doi:10.1038/pr.2016.128.

- 1 2 3 4 Warner Chilcott (March 2005). "ESTRACE TABLETS, (estradiol tablets, USP)" (PDF). fda.gov. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Pfizer (August 2008). "ESTRING (estradiol vaginal ring)" (PDF).

- ↑ Cheng ZN, Shu Y, Liu ZQ, Wang LS, Ou-Yang DS, Zhou HH (February 2001). "Role of cytochrome P450 in estradiol metabolism in vitro". Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 22 (2): 148–54. PMID 11741520.

- ↑ Soltysik K, Czekaj P (April 2013). "Membrane estrogen receptors - is it an alternative way of estrogen action?". J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 64 (2): 129–42. PMID 23756388.

- ↑ Prossnitz ER, Barton M (May 2014). "Estrogen biology: New insights into GPER function and clinical opportunities". Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 389 (1–2): 71–83. PMC 4040308

. PMID 24530924. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2014.02.002.

. PMID 24530924. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2014.02.002. - ↑ Jennifer E. Dietrich (18 June 2014). Female Puberty: A Comprehensive Guide for Clinicians. Springer. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-1-4939-0912-4.

- ↑ Randy Thornhill; Steven W. Gangestad (25 September 2008). The Evolutionary Biology of Human Female Sexuality. Oxford University Press. pp. 145–. ISBN 978-0-19-988770-5.

- ↑ Raine-Fenning NJ, Brincat MP, Muscat-Baron Y (2003). "Skin aging and menopause : implications for treatment". Am J Clin Dermatol. 4 (6): 371–8. PMID 12762829.

- ↑ Chris Hayward (31 July 2003). Gender Differences at Puberty. Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-0-521-00165-6.

- ↑ Shlomo Melmed; Kenneth S. Polonsky; P. Reed Larsen; Henry M. Kronenberg (11 November 2015). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1105–. ISBN 978-0-323-34157-8.

- ↑ Richard E. Jones; Kristin H. Lopez (28 September 2013). Human Reproductive Biology. Academic Press. pp. 19–. ISBN 978-0-12-382185-0.

- ↑ Ethel Sloane (2002). Biology of Women. Cengage Learning. pp. 496–. ISBN 0-7668-1142-5.

- ↑ Tekoa L. King; Mary C. Brucker (25 October 2010). Pharmacology for Women's Health. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 1022–. ISBN 978-0-7637-5329-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Rogerio A. Lobo (5 June 2007). Treatment of the Postmenopausal Woman: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Academic Press. pp. 177, 217–226, 770–771. ISBN 978-0-08-055309-2.

- ↑ David Warshawsky; Joseph R. Landolph Jr. (31 October 2005). Molecular Carcinogenesis and the Molecular Biology of Human Cancer. CRC Press. pp. 457–. ISBN 978-0-203-50343-0.

- ↑ Goldstein I, Meston CM, Davis S, Traish A (17 November 2005). Women's Sexual Function and Dysfunction: Study, Diagnosis and Treatment. CRC Press. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-1-84214-263-9.

- ↑ Acevedo-Rodriguez A, Mani SK, Handa RJ (2015). "Oxytocin and Estrogen Receptor β in the Brain: An Overview". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 6: 160. PMC 4606117

. PMID 26528239. doi:10.3389/fendo.2015.00160.

. PMID 26528239. doi:10.3389/fendo.2015.00160. - ↑ N. V. Bhagavan (26 September 2001). Medical Biochemistry. Academic Press. pp. 709–. ISBN 978-0-08-051139-9.

- ↑ Ross Cameron; George Feuer; Felix de la Iglesia (6 December 2012). Drug-Induced Hepatotoxicity. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 551–. ISBN 978-3-642-61013-4.

- 1 2 Shellenberger, T. E. (1986). "Pharmacology of estrogens": 393–410. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-4145-8_36.

Ethinyl estradiol is a synthetic and comparatively potent estrogen. As a result of the alkylation in 17-C position it is not a substrate for 17β dehydrogenase, an enzyme which transforms natural estradiol-17β to the less potent estrone in target organs.

- 1 2 3 Sitruk-Ware R, Nath A (2011). "Metabolic effects of contraceptive steroids". Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 12 (2): 63–75. PMID 21538049. doi:10.1007/s11154-011-9182-4.

- ↑ Fruzzetti F, Trémollieres F, Bitzer J (2012). "An overview of the development of combined oral contraceptives containing estradiol: focus on estradiol valerate/dienogest". Gynecological Endocrinology : the Official Journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology. 28 (5): 400–8. PMC 3399636

. PMID 22468839. doi:10.3109/09513590.2012.662547.

. PMID 22468839. doi:10.3109/09513590.2012.662547. - ↑ na. Newnes. pp. 486–. ISBN 978-0-444-54286-1.

- 1 2 3 4 O'Connell MB (1995). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacologic variation between different estrogen products". J Clin Pharmacol. 35 (9 Suppl): 18S–24S. PMID 8530713.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kuhnz, W.; Blode, H.; Zimmermann, H. (1993). "Pharmacokinetics of Exogenous Natural and Synthetic Estrogens and Antiestrogens". 135 / 2: 261–322. ISSN 0171-2004. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-60107-1_15.

- ↑ Michael Oettel; Ekkehard Schillinger (6 December 2012). Estrogens and Antiestrogens I: Physiology and Mechanisms of Action of Estrogens and Antiestrogens. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 235–237. ISBN 978-3-642-58616-3.

- 1 2 3 Düsterberg B, Nishino Y (1982). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacological features of oestradiol valerate". Maturitas. 4 (4): 315–24. PMID 7169965.

- 1 2 3 4 A. Wayne Meikle (1 June 1999). Hormone Replacement Therapy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 380–. ISBN 978-1-59259-700-0.

- ↑ V. H. T. James; J. R. Pasqualini (22 October 2013). Hormonal Steroids: Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress on Hormonal Steroids. Elsevier Science. pp. 821–. ISBN 978-1-4831-9067-9.

- 1 2 3 Rebekah Wang-Cheng; Joan M. Neuner; Vanessa M. Barnabei (2007). Menopause. ACP Press. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-1-930513-83-9.

- 1 2 John J.B. Anderson; Sanford C. Garner (24 October 1995). Calcium and Phosphorus in Health and Disease. CRC Press. pp. 215–216. ISBN 978-0-8493-7845-4.

- ↑ Eef Hogervorst (24 September 2009). Hormones, Cognition and Dementia: State of the Art and Emergent Therapeutic Strategies. Cambridge University Press. pp. 82–. ISBN 978-0-521-89937-6.

- ↑ Jose Russo; Irma H. Russo (28 June 2011). Molecular Basis of Breast Cancer: Prevention and Treatment. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 92–. ISBN 978-3-642-18736-0.

- ↑ Sue E. Huether; Kathryn L. McCance (27 December 2013). Understanding Pathophysiology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 845–. ISBN 978-0-323-29343-3.

- ↑ Ruggiero RJ, Likis FE (2002). "Estrogen: physiology, pharmacology, and formulations for replacement therapy". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 47 (3): 130–8. PMID 12071379. doi:10.1016/s1526-9523(02)00233-7.

- ↑ Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB, Sklar LA (2007). "GPR30: A G protein-coupled receptor for estrogen". Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 265-266: 138–42. PMC 1847610

. PMID 17222505. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.010.

. PMID 17222505. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.010. - ↑ Marc A. Fritz; Leon Speroff (28 March 2012). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 753–. ISBN 978-1-4511-4847-3.

- 1 2 Alkjaersig N, Fletcher AP, de Ziegler D, Steingold KA, Meldrum DR, Judd HL (1988). "Blood coagulation in postmenopausal women given estrogen treatment: comparison of transdermal and oral administration". J. Lab. Clin. Med. 111 (2): 224–8. PMID 2448408.

- 1 2 Weissberger AJ, Ho KK, Lazarus L (1991). "Contrasting effects of oral and transdermal routes of estrogen replacement therapy on 24-hour growth hormone (GH) secretion, insulin-like growth factor I, and GH-binding protein in postmenopausal women". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 72 (2): 374–81. PMID 1991807. doi:10.1210/jcem-72-2-374.

- 1 2 Sonnet E, Lacut K, Roudaut N, Mottier D, Kerlan V, Oger E (2007). "Effects of the route of oestrogen administration on IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 in healthy postmenopausal women: results from a randomized placebo-controlled study". Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 66 (5): 626–31. PMID 17492948. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02783.x.

- 1 2 Nugent AG, Leung KC, Sullivan D, Reutens AT, Ho KK (2003). "Modulation by progestogens of the effects of oestrogen on hepatic endocrine function in postmenopausal women". Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 59 (6): 690–8. PMID 14974909. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01907.x.

- 1 2 Isotton, A. L.; Wender, M. C. O.; Casagrande, A.; Rollin, G.; Czepielewski, M. A. (2011). "Effects of oral and transdermal estrogen on IGF1, IGFBP3, IGFBP1, serum lipids, and glucose in patients with hypopituitarism during GH treatment: a randomized study" (PDF). European Journal of Endocrinology. 166 (2): 207–213. ISSN 0804-4643. PMID 22108915. doi:10.1530/EJE-11-0560.

- 1 2 Jasonni VM, Bulletti C, Naldi S, Ciotti P, Di Cosmo D, Lazzaretto R, et al. (1988). "Biological and endocrine aspects of transdermal 17 beta-oestradiol administration in post-menopausal women". Maturitas. 10 (4): 263–70. PMID 3226336. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(88)90062-x.

- ↑ Dansuk R, Unal O, Karageyim Y, Esim E, Turan C (2004). "Evaluation of the effect of tibolone and transdermal estradiol on triglyceride level in hypertriglyceridemic and normotriglyceridemic postmenopausal women". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 18 (5): 233–9. PMID 15346658. doi:10.1080/09513590410001715199.

- ↑ Casper RF, Yen SS (1981). "Rapid absorption of micronized estradiol-17 beta following sublingual administration". Obstet Gynecol. 57 (1): 62–4. PMID 7454177.

- ↑ Pines A, Averbuch M, Fisman EZ, Rosano GM (1999). "The acute effects of sublingual 17beta-estradiol on the cardiovascular system". Maturitas. 33 (1): 81–5. PMID 10585176. doi:10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00036-5.

- ↑ Price TM, Blauer KL, Hansen M, Stanczyk F, Lobo R, Bates GW (1997). "Single-dose pharmacokinetics of sublingual versus oral administration of micronized 17 beta-estradiol". Obstet Gynecol. 89 (3): 340–5. PMID 9052581. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(96)00513-3.

- ↑ Dooley, Mukta; Spencer, Caroline M.; Ormrod, Douglas (2001). "Estradiol-Intranasal". Drugs. 61 (15): 2243–2262. ISSN 0012-6667. doi:10.2165/00003495-200161150-00012.

- ↑ Lopes P, Rozenberg S, Graaf J, Fernandez-Villoria E, Marianowski L (2001). "Aerodiol versus the transdermal route: perspectives for patient preference". Maturitas. 38 Suppl 1: S31–9. PMID 11390122.

- ↑ Jeffrey K. Aronson (21 February 2009). Meyler's Side Effects of Endocrine and Metabolic Drugs. Elsevier. pp. 173–. ISBN 978-0-08-093292-7.

- ↑ Janice Ryden; Paul D. Blumenthal (2002). Practical Gynecology: A Guide for the Primary Care Physician. ACP Press. pp. 436–. ISBN 978-0-943126-94-4.

- ↑ Sahin FK, Koken G, Cosar E, Arioz DT, Degirmenci B, Albayrak R, Acar M (2008). "Effect of Aerodiol administration on ocular arteries in postmenopausal women". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 24 (4): 173–7. PMID 18382901. doi:10.1080/09513590701807431.

300 μg 17β-estradiol (Aerodiol®; Servier, Chambrayles-Tours, France) was administered via the nasal route by a gynecologist. This product is unavailable after March 31, 2007 because its manufacturing and marketing are being discontinued.

- ↑ http://www.netdoctor.co.uk/medicines/a8266/aerodiol-nasal-spray-discontinued-in-the-uk-december-2006/

- 1 2 3 4 "EstroGel® 0.06% (Estradiol Gel) for Topical Use FDA Label" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ↑ Hall G, Blombäck M, Landgren BM, Bremme K (2002). "Effects of vaginally administered high estradiol doses on hormonal pharmacokinetics and hemostasis in postmenopausal women". Fertil. Steril. 78 (6): 1172–7. PMID 12477507. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04285-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Oriowo MA, Landgren BM, Stenström B, Diczfalusy E (April 1980). "A comparison of the pharmacokinetic properties of three estradiol esters". Contraception. 21 (4): 415–24. PMID 7389356. doi:10.1016/s0010-7824(80)80018-7.

- 1 2 3 Sierra-Ramírez JA, Lara-Ricalde R, Lujan M, Velázquez-Ramírez N, Godínez-Victoria M, Hernádez-Munguía IA, et al. (2011). "Comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics after subcutaneous and intramuscular administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate (25 mg) and estradiol cypionate (5 mg)". Contraception. 84 (6): 565–70. PMID 22078184. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.03.014.

- 1 2 M. Notelovitz; P.A. van Keep (6 December 2012). The Climacteric in Perspective: Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress on the Menopause, held at Lake Buena Vista, Florida, October 28–November 2, 1984. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 397, 399. ISBN 978-94-009-4145-8.

[...] following the menopause, circulating estradiol levels decrease from a premenopausal mean of 120 pg/ml to only 13 pg/ml.

- ↑ Nagrath Arun; Malhotra Narendra; Seth Shikha (15 December 2012). Progress in Obstetrics and Gynecology--3. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. 416–418. ISBN 978-93-5090-575-3.

- ↑ Ulrich U, Pfeifer T, Lauritzen C (1994). "Rapid increase in lumbar spine bone density in osteopenic women by high-dose intramuscular estrogen-progestogen injections. A preliminary report". Horm. Metab. Res. 26 (9): 428–31. PMID 7835827. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1001723.

- ↑ C. Christian; B. von Schoultz (15 March 1994). Hormone Replacement Therapy: Standardized or Individually Adapted Doses?. CRC Press. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-1-85070-545-1.

The mean integrated estradiol level during a full 28-day normal cycle is around 80 pg/ml.

- ↑ Eugenio E. Müller; Robert M. MacLeod (6 December 2012). Neuroendocrine Perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-1-4612-3554-5.

[...] [premenopausal] mean [estradiol] concentration of 150 pg/ml [...]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis US. 2000. pp. 404–406. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ↑ IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; World Health Organization; International Agency for Research On Cancer (2007). Combined Estrogen-Progestogen Contraceptives and Combined Estrogen-Progestogen Menopausal Therapy. World Health Organization. p. 384. ISBN 978-92-832-1291-1. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- 1 2 Archana Desai; Mary Lee (7 May 2007). Gibaldi's Drug Delivery Systems in Pharmaceutical Care. ASHP. p. 337. ISBN 978-1-58528-136-7. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- 1 2 Fluhmann CF (1938). "Estrogenic Hormones: Their Clinical Usage". Cal West Med. 49 (5): 362–6. PMC 1659459

. PMID 18744783.

. PMID 18744783. - 1 2 Reilly WA (1941). "Estrogens: Their Use in Pediatrics". Cal West Med. 55 (5): 237–9. PMC 1634235

. PMID 18746057.

. PMID 18746057. - ↑ Martin PL, Burnier AM, Greaney MO (1972). "Oral menopausal therapy using 17- micronized estradiol. A preliminary study of effectiveness, tolerance and patient preference". Obstet Gynecol. 39 (5): 771–4. PMID 5023261.

- ↑ Rigg LA, Milanes B, Villanueva B, Yen SS (1977). "Efficacy of intravaginal and intranasal administration of micronized estradiol-17beta". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 45 (6): 1261–4. PMID 591620. doi:10.1210/jcem-45-6-1261.

- ↑ http://www.kegg.jp/entry/D00105

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 https://www.drugs.com/international/estradiol.html

- ↑ J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 897–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- 1 2 I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ↑ Newton JR, D'arcangues C, Hall PE (1994). "A review of "once-a-month" combined injectable contraceptives". J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). 4 Suppl 1: S1–34. PMID 12290848. doi:10.3109/01443619409027641.

- ↑ http://www.wjpps.com/download/article/1412071798.pdf

- ↑ Rowlands, S (2009). "New technologies in contraception". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 116 (2): 230–239. ISSN 1470-0328. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01985.x.

- ↑ http://adisinsight.springer.com/drugs/800038089

- ↑ Pickar JH, Bon C, Amadio JM, Mirkin S, Bernick B (2015). "Pharmacokinetics of the first combination 17β-estradiol/progesterone capsule in clinical development for menopausal hormone therapy". Menopause. 22 (12): 1308–16. PMC 4666011

. PMID 25944519. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000467.

. PMID 25944519. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000467. - ↑ Kaunitz AM, Kaunitz JD (2015). "Compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: time for a reality check?". Menopause. 22 (9): 919–20. PMID 26035149. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000484.

- ↑ Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH (2016). "Update on medical and regulatory issues pertaining to compounded and FDA-approved drugs, including hormone therapy". Menopause. 23 (2): 215–23. PMC 4927324

. PMID 26418479. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000523.

. PMID 26418479. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000523. - ↑ Fugh-Berman A, Bythrow J (2007). "Bioidentical hormones for menopausal hormone therapy: variation on a theme". J Gen Intern Med. 22 (7): 1030–4. PMC 2219716

. PMID 17549577. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0141-4.

. PMID 17549577. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0141-4.