Conidium

Conidia, sometimes termed asexual chlamydospores or chlamydoconidia,[1] are asexual,[2] non-motile spores of a fungus, from the Greek word for dust, κόνις kónis.[3] They are also called mitospores due to the way they are generated through the cellular process of mitosis. The two new haploid cells are genetically identical to the haploid parent, and can develop into new organisms if conditions are favorable, and serve in biological dispersal.

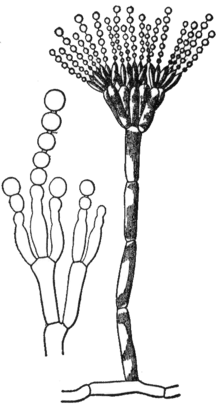

Asexual reproduction in ascomycetes (the phylum Ascomycota) is by the formation of conidia, which are borne on specialized stalks called conidiophores. The morphology of these specialized conidiophores is often distinctive of a specific species and can therefore be used in identification of the species.

The terms microconidia and macroconidia are sometimes used.[4]

Conidiogenesis

There are two main types of conidium development:[5]

- Blastic conidiogenesis, where the spore is already evident before it separates from the conidiogenic hypha which is giving rise to it, and

- Thallic conidiogenesis, where first a cross-wall appears and thus the created cell develops into a spore.

Conidia germination

A conidium may form germ tubes (germination tubes) and/or conidial anastomosis tubes (CATs) in specific conditions. These two are some of the specialized hyphae that are formed by fungal conidia. The germ tubes will grow to form the hyphae and fungal mycelia. The conidial anastomosis tubes are morphologically and physiologically distinct from germ tubes. After conidia are induced to form conidial anastomosis tubes, they grow homing toward each other, and they fuse. Once fusion happens, the nuclei can pass through fused CATs. These are events of fungal vegetative growth and not sexual reproduction. Fusion between these cells seems to be important for some fungi during early stages of colony establishment. The production of these cells has been suggested to occur in 73 different species of fungi.[6][7]

Structures for release of conidia

Conidiogenesis is an important mechanism of spread of plant pathogens. In some cases, specialized macroscopic fruiting structures perhaps 1mm or so in diameter containing masses of conidia are formed under the skin of the host plant and then erupt through the surface and allow the spores to be distributed by wind and rain. One of these structures is called a conidioma (plural: conidiomata).[8][9]

Two important types of conidiomata, distinguished by their form, are:

- pycnidia, (singular: pycnidium) which are flask-shaped, and

- acervuli (singular: acervulus), which have a simpler cushion-like form.

Pycnidial conidiomata or pycnidia form in the fungal tissue itself, and are shaped like a bulging vase. The spores are released through a small opening at the apex, the ostiole.

Acervular conidiomata, or acervuli, are cushion-like structures that form within the tissues of a host organism:

- subcuticular, lying under the outer layer of the plant (the cuticle),

- intraepidermal, inside the outer cell layer (the epidermis),

- subepidermal, under the epidermis, or deeper inside the host.

Mostly they develop a flat layer of relatively short conidiophores which then produce masses of spores. The increasing pressure leads to the splitting of the epidermis and cuticle and allows release of the conidia from the tissue.

Health issues

Conidia are always present in the air, but levels fluctuate from day to day and with the seasons. An average person inhales 40 conidia per hour.

Conidia are often the method by which some normally harmless but heat-tolerating (thermotolerant), common fungi establish infection in certain types of severely immunocompromised patients (usually acute leukemia patients on induction chemotherapy, AIDS patients with superimposed B-cell lymphoma, bone marrow transplantation patients, or major organ transplant patients suffering from graft versus host disease). Their immune system is not strong enough to fight off the fungus, and it may, for example, colonise the lung, resulting in a pulmonary infection.

See also

References

- ↑ Jansonius, D.C., Gregor, Me., 1996. Palynology: principles and applications. American association of stratigraphic palynologists foundation.

- ↑ Osherov, Nir; May, Gregory S (2001). "The molecular mechanisms of conidial germination". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 199 (2): 153. PMID 11377860. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10667.x.

- ↑ Conidium in the Collins Dictionary

- ↑ Ohara, T.; Inoue, I; Namiki, F; Kunoh, H; Tsuge, T (2004). "REN1 is Required for Development of Microconidia and Macroconidia, but Not of Chlamydospores, in the Plant Pathogenic Fungus Fusarium oxysporum". Genetics. 166 (1): 113–24. PMC 1470687

. PMID 15020411. doi:10.1534/genetics.166.1.113.

. PMID 15020411. doi:10.1534/genetics.166.1.113. - ↑ Sigler, Lynne (1989). "Problems in application of the terms 'blastic' And 'thallic' To modes of conidiogenesis in some onygenalean fungi". Mycopathologia. 106 (3): 155–61. PMID 2682248. doi:10.1007/BF00443056.

- ↑ Friesen, Timothy L; Stukenbrock, Eva H; Liu, Zhaohui; Meinhardt, Steven; Ling, Hua; Faris, Justin D; Rasmussen, Jack B; Solomon, Peter S; McDonald, Bruce A; Oliver, Richard P (2006). "Emergence of a new disease as a result of interspecific virulence gene transfer". Nature Genetics. 38 (8): 953. PMID 16832356. doi:10.1038/ng1839.

- ↑ Gabriela Roca, M.; Read, Nick D.; Wheals, Alan E. (2005). "Conidial anastomosis tubes in filamentous fungi". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 249 (2): 191. PMID 16040203. doi:10.1016/j.femsle.2005.06.048.

- ↑ diagrams at the Forest Pathology site

- ↑ d'Arcy (2001). "Illustrated Glossary of Plant Pathology". The Plant Health Instructor. doi:10.1094/PHI-I-2001-0219-01.

External links

-

"Conidia". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

"Conidia". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.