Michel Eugène Chevreul

| Michel Eugène Chevreul | |

|---|---|

Michel Eugène Chevreul | |

| Born |

31 August 1786 Angers, France |

| Died |

9 April 1889 (aged 102) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Known for |

Fatty acids Margarine |

| Notable awards |

Copley Medal (1857) Albert Medal (1873) |

Michel Eugène Chevreul (31 August 1786 – 9 April 1889)[1] was a French chemist whose work with fatty acids led to early applications in the fields of art and science. He is credited with the discovery of margaric acid, creatine, and designing an early form of soap made from animal fats and salt. He lived to 102 and was a pioneer in the field of gerontology. He is also one of the 72 people whose names are inscribed on the Eiffel Tower; of those 72 scientists and engineers, Chevreul was one of only two who were still alive when Eiffel planted the French Tricolor on the top of the tower on 31 March 1889.

Biography

Chevreul was born in the town of Angers, France, where his father was a physician. Chevreul's birth certificate, kept in the registry book of Angers, bears the signature of his father, grandfather, and a great-uncle, all of whom were surgeons.

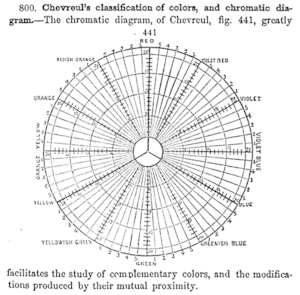

At about the age of seventeen Chevreul went to Paris and entered L. N. Vauquelin's chemical laboratory, afterwards becoming his assistant at the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle (National Museum of Natural History) in the Jardin des Plantes. In 1813 Chevreul was appointed professor of chemistry at the Lycée Charlemagne, and subsequently undertook the directorship of the Gobelins tapestry works, where he carried out his research on colour contrasts. (In 1839, he published the results of his research under the title De la loi du contraste simultané des couleurs; It was translated it into English and published in 1854 under the title The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors.) In 1826 Chevreul became a member of the Academy of Sciences, and in the same year was elected a foreign member of the Royal Society of London, whose Copley Medal he was awarded in 1857. In 1829, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1868.[2]

Chevreul succeeded his master, Vauquelin, as professor of organic chemistry at the National Museum of Natural History in 1830, and thirty-three years later assumed its directorship also; this he relinquished in 1879, though he still retained his professorship. A gold medal was minted for the occasion of Chevreul's 100th birthday in 1886, and it was celebrated as a national event. Chevreul received letters of commendation from many heads of state and monarchs, including Queen Victoria. He had a series of recorded meetings with Félix Nadar, with Nadar's son Paul taking photographs, making up the first photo-interview in history. It was a fitting tribute to a man who lived through the entire French Revolution and lived to see the unveiling of the Eiffel Tower. His name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

Chevreul began to study the effects of aging on the human body shortly before his death at the age of 102, which occurred in Paris on 9 April 1889. He was honoured with a public funeral. In 1901 a statue was erected to his memory in the museum with which he was connected for so many years.

Chevreul's work

Chevreul's scientific work covered a wide range, but he is best known for the classical researches he carried out on animal fats, published in 1823 (Recherches sur les corps gras d'origine animale). These enabled him to elucidate the true nature of soap; he was also able to discover the composition of stearin, a white substance found in the solid parts of most animal and vegetable fats, and olein, the liquid part of any fat, and to isolate stearic and oleic acids, the names of which he invented. This work led to important improvements in the processes of candle-manufacture.

Chevreul was a determined enemy of charlatanism in every form, and a complete sceptic as to the "scientific" psychical research or spiritualism which had begun in his time. His research on the "magic pendulum", Dowsing rods and table-turning is revolutionary. In an open letter to André-Marie Ampère in 1833, and his 1854 paper "De la baguette", Chevreul explains how human muscular reactions, totally involuntary and subconscious, are responsible for seemingly magical movements. In the end Chevreul discovered that once a person holding divining rods/magic pendulum became aware of the brain's reaction, the movements stopped and could not be willingly reproduced. His was one of the earliest explanations of the ideomotor effect.[3]

Chevreul was also influential in the world of art. After being named director of the dye works at the Gobelins Manufactory in Paris, he received many complaints about the dyes being used there. In particular, the blacks appeared different when used next to blues. He determined that the yarn's perceived color was influenced by other surrounding yarns. This led to a concept known as simultaneous contrast.

Chevreul is also linked to what is sometimes called Chevreul's illusion, the bright edges that seem to exist between adjacent strips of identical colors having different intensities. See Chevreul's The Laws of Contrast of Colour for more information.[4]

Chevreul's work addressed painting with the aim of reproducing nature as closely as possible, by separating effects of light and chiaroscuro, which the artist must repeat, from those of color contrast, which would apply to the paint's own color and so be exaggerated. Yet the color principle subsequently had a great influence on advanced art in Europe, particularly Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism and Orphism.

Bibliography

- Chevreul, Michel Eugène (1823). Recherches chimiques sur les corps gras d'origine animale. Paris: F. G. Levrault.

- Chevreul, Michel Eugène (1830). Leçons de chimie appliquée à la teinture. Paris: Pichon et Didier.

- Chevreul, Michel Eugène (1854). De la baguette divinatoire, du pendule dit explorateur et des tables tournantes, au point de vue de I'histoire, de la critique et de la methode experimental. Paris: Mallet-Bachelier.

- Chevreul, Michel Eugène (1839). De la loi du contraste simultané des couleurs et de l'assortiment des objets colorés. - translated into English by Charles Martel as The principles of harmony and contrast of colours (1854)

- Chevreul, Michel Eugène (1855). The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colours, and Their Applications to the Arts (2 ed.). London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. (English translation)

- Chevreul, Michel Eugène (1866). Histoire des connaissances chimiques. Paris: L. Guérim.

- Chevreul, Michel Eugène (1870). De la méthode a posteriori expérimentale, et de la généralité de ses applications. Paris: Dunod.

- Chevreul, Michel Eugène (1886). Oeuvres scientifiques de Michel-Eugène Chevreul: doyen des étudiants de France 1806-1886. Paris: Rouen, Impr. J. Lecerf.

Notes

- ↑ McKenna, Charles. "Michel-Eugène Chevreul." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. accessed 10 May 2008

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter C" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ↑ Spitz, Herman H.; Marcuard, Yves (July–August 2001). "Chevreul's Report on the Mysterious Oscillations of the Hand-Held Pendulum". Skeptical Inquirer. Center for Inquiry. 25 (4): 35–9.

- ↑ See page 4 and plate 1 of Chevreul, Michel Eugène (1861). The Laws of Contrast of Colour. London: Routledge, Warne, and Routledge.- English translation by John Spanton

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chevreul, Michel Eugène". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chevreul, Michel Eugène". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Carmichael, E B (Apr 1973). "Michel Eugene Chevreul. Experimental chemist and physicist: lipids and dyes". The Alabama journal of medical sciences. 10 (2): 223–32. PMID 4582698.

- Kalugai, I (Jun 1980). "Michel-Eugène Chevreul, 1786-1889". Korot. 7 (11–12): 796–802. PMID 11630731.

- Lemay, Pierre; Oesper, Ralph (1948). "Michel Eugene Chevreul (1786 – 1889)". Journal of Chemical Education. 25 (2): 62–70. doi:10.1021/ed025p62.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Michel Eugène Chevreul. |

- Obituary in:

"Obituary Notes". Popular Science Monthly. 35. June 1889.

"Obituary Notes". Popular Science Monthly. 35. June 1889. - Chevreul on cyberlipid.org

- Paper on Chevreul's life-long work on colour contrast by Prof Georges Roque, Paris

- Chevreul's (1861) Exposé d’un moyen de définir et de nommer les couleurs. Atlas. - digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library

- Chevreul's (1888) Des couleurs et de lueurs applications aux arts industriels a l'aide des cercles chromatiques - digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library