Hmongic languages

| Hmongic | |

|---|---|

| Miao | |

| Ethnicity | Miao people |

| Geographic distribution | China, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, and the US |

| Linguistic classification |

|

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | hmn |

| Glottolog | hmon1337[1] |

|

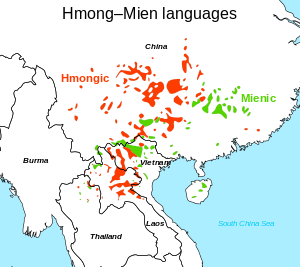

Hmongic languages are in red | |

The Hmongic also known as Miao languages include the various languages spoken by the Miao people (such as Hmong, Hmu, and Xong), Pa-Hng, and the "Bunu" languages used by non-Mien-speaking Yao people.

Name

The most common name used for the languages is Miao (苗), the Chinese name and the one used by Miao in China. However, Hmong is more familiar in the West, due to Hmong emigration. Many overseas Hmong prefer the name Hmong, and claim that Miao is both inaccurate and pejorative, though it is generally considered neutral by the Miao community in China.

Of the Hmongic languages spoken by ethnic Miao, there are a number of overlapping names. The three branches are as follows,[2] as named by Purnell (in English and Chinese), Ma, and Ratliff, as well as the descriptive names based on the patterns and colors of traditional dress:

| Glottolog | Native name | Purnell | Chinese name | Ma | Ratliff | Dress-color name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

west2803 | —* | Sichuan–Guizhou–Yunnan Miao | 川黔滇苗 Chuanqiandian Miao | Western Miao | West Hmongic | White, Blue/Green, Flowery, etc. |

nort2748 | Xong | Western Hunan Miao | 湘西苗 Xiangxi Miao | Eastern Miao | North Hmongic | Red Miao/Meo |

east2369 | Hmu | Eastern Guizhou Miao | 黔东苗 Qiandong Miao | Central Miao | East Hmongic | Black Miao |

* No common name. Miao speakers use forms like Hmong (Mong), Hmang (Mang), Hmao, Hmyo. Yao speakers use names based on Nu.

The Hunan Province Gazetteer (1997) gives the following autonyms for various peoples classified by the Chinese government as Miao.

- Xiangxi Prefecture: gho Xong (guo Xiong 果雄), ghe Xong (ge Xiong 仡熊); guo Chu 果楚 (ceremonial)

- Luxi County and Guzhang County: ghao So (Suo 缩), te Suang (Shuang 爽)

- Jingzhou County: Hmu (Mu 目), (Nai Mu 乃目)

- Chengbu County: Hmao (Mao 髳)

Writing

The Hmongic languages have been written with at least a dozen different scripts,[3] none of which has been universally accepted among Hmong people as standard. Tradition has it that the ancestors of the Hmong, the Nanman, had a written language with a few pieces of significant literature. When the Han-era Chinese began to expand southward into the land of the Hmong, whom they considered barbarians, the script of the Hmong was lost, according to many stories. Allegedly, the script was preserved in the clothing. Attempts at revival were made by the creation of a script in the Qing Dynasty, but this was also brutally suppressed and no remnant literature has been found. Adaptations of Chinese characters have been found in Hunan, recently.[4] However, this evidence and mythological understanding is disputed. For example, according to Professor S. Robert Ramsey, there was no writing system among the Miao until the missionaries created them.[5] It is currently unknown for certain whether or not the Hmong had a script historically.

Around 1905, Samuel Pollard introduced the Pollard script, for the A-Hmao language, an abugida inspired by Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics, by his own admission.[6] Several other syllabic alphabets were designed as well, the most notable being Shong Lue Yang's Pahawh Hmong script, which originated in Laos for the purpose of writing Hmong Daw, Hmong Njua, and other dialects of the standard Hmong language.

In the 1950s, pinyin-based Latin alphabets were devised by the Chinese government for three varieties of Miao: Xong, Hmu, and Chuangqiandian (Hmong), as well as a Latin alphabet for A-Hmao to replace the Pollard script (now known as "Old Miao"), though Pollard remains popular. This meant that each of the branches of Miao in the classification of the time had a separate written standard.[7] Wu and Yang (2010) believe that standards should be developed for each of the six other primary varieties of Chuangqiandian as well, although the position of Romanization in the scope of Hmong language preservation remains a debate. Romanization remains common in China and the United States, while versions of the Lao and Thai scripts remain common in Thailand and Laos.

Classification

Hmongic is one of the primary branches of the Hmong–Mien language family, with the other being Mienic. Hmongic is a diverse group of perhaps twenty languages, based on mutual intelligibility, but several of these are dialectically quite diverse in phonology and vocabulary, and are not considered to be single languages by their speakers. There are probably over thirty languages taking this into account.[8] Four classifications are outlined below, though the details of the West Hmongic branch are left for that article.

Mo Piu, first documented in 2009, was reported by Geneviève Caelen-Haumont (2011) to be a divergent Hmongic language. It is currently unclassified. Similarly, Ná-Meo is not addressed in the classifications below, but is believed by Nguyen (2007) to be closest to Hmu (Qiandong Miao).

Strecker (1987)

Strecker's classification is as follows:[8]

- Hmongic (Miao)

In a follow-up to that paper in the same publication, he tentatively removed Pa-Hng, Wunai, Jiongnai, and Yunuo, positing that they may be independent branches of Miao–Yao, with the possibility that Yao was the first of these to branch off, effectively meaning that Miao/Hmongic would consist of six branches: She (Ho-Nte), Pa-Hng, Wunai, Jiongnai, Yunuo, and everything else.[9] In addition, the 'everything else' would include nine distinct but unclassified branches, which were not addressed by either Matisoff or Ratliff (see West Hmongic#Strecker).

Matisoff (2001)

Matisoff followed the basic outline of Strecker 1987, apart from consolidating the Bunu languages and leaving She unclassified:

- Hmongic (Miao)

- Bunu

- Chuanqiangdian Miao (See)

- Pa-Hng

- Qiandong Miao (Hmu, 3 languages)

- Xiangxi Miao (Xong, 2 languages)

Wang & Deng (2003)

Wang & Deng (2003) is one of the few Chinese sources which integrate the Bunu languages into Hmongic on purely linguistic grounds. They find the following pattern in the statistics of core Swadesh vocabulary:[10]

- She

- (main branch)

- (Hunan–Guangxi)

- Jiongnai

- (other)

- Western Hunan (Northern Hmongic / Xong)

- Younuo–Pa-Hng

- (Guizhou–Yunnan)

- Eastern Guizhou (Eastern Hmongic / Hmu)

- (Western)

- (Hunan–Guangxi)

Matisoff (2006)

Matisoff 2006 outlined the following. Not all varieties are listed.[11]

- Northern Hmong = West Hunan (Xong)

- Western Hmong (See)

- Central Hmong

- Eastern Guizhu (Hmu)

- Patengic

Matisoff also indicates Hmongic influence on Gelao in his outline.

Ratliff (2010)

The classification below is from Martha Ratliff (2010:3).[12] Note that Chinese linguist Mao Zongwu now considers Younuo and Wunai (Hm Nai) to form a branch with Pa-Hng.[13]

- Hmongic (Miao)

- Pa-Hng – 32,000 speakers

- (Main branch)

- Jiongnai & Ho Ne (She) – 2,000 speakers

- (Core Hmongic)

- West Hmongic (Chuanqiandian)

- North Hmongic (also known as Xong (Qo Xiong)) – 900,000 speakers mostly in Hunan

- East Hmongic (also known as Hmu) – 2,100,000 speakers mostly in Guizhou

Ratliff (2010) notes that Pa-Hng, Jiongnai, and Qo Xiong (North Hmongic) are phonologically conservative, as they retain many Proto-Hmongic features that have been lost in most other daughter languages. For instance, both Pa-Hng and Qo Xiong have vowel quality distinctions (and also tone distinctions in Qo Xiong) depending on whether or not the Proto-Hmong-Mien rime was open or closed. Both also retain the second part of Proto-Hmong-Mien diphthongs, which is lost in most other Hmongic languages, since they tend to preserve only the first part of Proto-Hmong-Mien diphthongs. Ratliff notes that the position of Qo Xiong (North Hmongic) is still quite uncertain. Since Qo Xiong preserves many archaic features not found in most other Hmongic languages, any future attempts at classifying the Hmong-Mien languages must also address the position of Qo Xiong.

Taguchi (2012)

Yoshihisa Taguchi's (2012) computational phylogenetic study classifies the Hmongic languages as follows.[14]

- Hmongic

Mixed languages

Due to intensive language contact, there are several language varieties in China which are thought to be mixed Miao–Chinese languages or Sinicized Miao. These include:

- Lingling (Linghua) of northern Guangxi

- Waxiang of western Hunan

- Laba 喇叭: more than 200,000 in Qinglong, Shuicheng, Pu'an, and Panxian in Guizhou; possibly a mixed Chinese and Miao language. The people are also called Huguangren 湖广人, because they claim their ancestors had migrated from Huguang[15]

- Baishi Miao 拜师苗 of Baishi District, Tianzhu County, eastern Guizhou, possibly a mixed Chinese and Miao (Hmu?) language[16]

Numerals

| Language | One | Two | Three | Four | Five | Six | Seven | Eight | Nine | Ten |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proto-Hmong-Mien | *ʔɨ | *ʔu̯i | *pjɔu | *plei | *prja | *kruk | *dzjuŋH | *jat | *N-ɟuə | *gju̯əp |

| Pa-Hng (Gundong) | ji˩ | wa˧˥ | po˧˥ | ti˧˥ | tja˧˥ | tɕu˥ | tɕaŋ˦ | ji˦˨ | ko˧ | ku˦˨ |

| Wunai (Longhui) | i˧˥ | ua˧˥ | po˧˥ | tsi˧˥ | pia˧˥ | tju˥ | tɕa˨˩ | ɕi˧˩ | ko˧ | kʰu˧˩ |

| Younuo | je˨ | u˧ | pje˧ | pwɔ˧ | pi˧ | tjo˧˥ | sɔŋ˧˩ | ja˨˩ | kiu˩˧ | kwə˨˩ |

| Jiongnai | ʔi˥˧ | u˦ | pa˦ | ple˦ | pui˦ | tʃɔ˧˥ | ʃaŋ˨ | ʑe˧˨ | tʃu˧ | tʃɔ˧˥ |

| She (Chenhu) | i˧˥ | u˨ | pa˨ | pi˧˥ | pi˨ | kɔ˧˩ | tsʰuŋ˦˨ | zi˧˥ | kjʰu˥˧ | kjʰɔ˧˥ |

| Western Xiangxi Miao (Layiping) | ɑ˦ | ɯ˧˥ | pu˧˥ | pʐei˧˥ | pʐɑ˧˥ | ʈɔ˥˧ | tɕoŋ˦˨ | ʑi˧ | tɕo˧˩ | ku˧ |

| Eastern Xiangxi Miao (Xiaozhang) | a˧ | u˥˧ | pu˥˧ | ɬei˥˧ | pja˥˧ | to˧ | zaŋ˩˧ | ʑi˧˥ | gɯ˧˨ | gu˧˥ |

| Northern Qiandong Miao (Yanghao) | i˧ | o˧ | pi˧ | l̥u˧ | tsa˧ | tʲu˦ | ɕoŋ˩˧ | ʑa˧˩ | tɕə˥ | tɕu˧˩ |

| Southern Qiandong Miao (Yaogao) | tiŋ˨˦ | v˩˧ | pai˩˧ | tl̥ɔ˩˧ | tɕi˩˧ | tju˦ | tsam˨ | ʑi˨˦ | tɕu˧˩ | tɕu˨˦ |

| Pu No (Du'an) | i˦˥˦ | aːɤ˦˥˦ | pe˦˥˦ | pla˦˥˦ | pu˦˥˦ | tɕu˦˨˧ | saŋ˨˩˨ | jo˦˨ | tɕu˨ | tɕu˦˨ |

| Nao Klao (Nandan) | i˦˨ | uɔ˦˨ | pei˦˨ | tlja˦˨ | ptsiu˧ | tɕau˧˨ | sɒ˧˩ | jou˥˦ | tɕau˨˦ | tɕau˥˦ |

| Nu Mhou (Libo) | tɕy˧ | yi˧ | pa˧ | tləu˧ | pja˧ | tjɤ˦ | ɕoŋ˧˩ | ja˧˨ | tɕɤ˥ | tɕɤ˧˨ |

| Nunu (Linyun) | i˥˧ | əu˥˧ | pe˥˧ | tɕa˥˧ | pɤ˥˧ | tɕu˨˧ | ʂɔŋ˨ | jo˨ | tɕu˧˨ | tɕu˨ |

| Tung Nu (Qibainong) | i˥ | au˧ | pe˧ | tɬa˧ | pjo˧ | ʈu˦˩ | sɔŋ˨˩ | ʑo˨˩ | tɕu˩˧ | tɕu˨˩ |

| Pa Na | ʔa˧˩ | ʔu˩˧ | pa˩˧ | tɬo˩˧ | pei˩˧ | kjo˧˥ | ɕuŋ˨ | ʑa˥˧ | tɕʰu˧˩˧ | tɕo˥˧ |

| Hmong Shuat (Funing) | ʔi˥ | ʔau˥ | pʲei˥ | plɔu˥ | pʒ̩˥ | tʃɔu˦ | ɕaŋ˦ | ʑi˨˩ | tɕa˦˨ | kɔu˨˩ |

| Hmong Dleub (Guangnan) | ʔi˥ | ʔɑu˥ | pei˥ | plou˥ | tʃɹ̩˥ | ʈɻou˦ | ɕã˦ | ʑi˨˩ | tɕuɑ˦˨ | kou˨˩ |

| Hmong Nzhuab (Maguan) | ʔi˥˦ | ʔau˦˧ | pei˥˦ | plou˥˦ | tʃɹ̩˥˦ | ʈou˦ | ɕaŋ˦ | ʑi˨ | tɕuɑ˦˨ | kou˨ |

| Northeastern Dian Miao (Shimenkan) | i˥ | a˥ | tsɿ˥[18] | tl̥au˥ | pɯ˥ | tl̥au˧ | ɕaɯ˧ | ʑʱi˧˩ | dʑʱa˧˥ | ɡʱau˧˩ |

| Raojia | i˦ | ɔ˦ | poi˦ | ɬɔ˦ | pja˦ | tju˧ | ɕuŋ˨ | ʑa˥˧ | tɕa˥ | tɕu˥˧ |

| Xijia Miao (Shibanzhai) | i˥ | u˧˩ | pzɿ˧˩[18] | pləu˧˩ | pja˧˩ | ʈo˨˦ | zuŋ˨˦ | ja˧ | ja˧˩ | ʁo˧˩ |

| Gejia | i˧ | a˧ | tsɪ˧˩ | plu˧ | tsia˧ | tɕu˥ | saŋ˧˩ | ʑa˩˧ | tɕa˨˦ | ku˩˧ |

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Hmongic". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Schein, Louisa (2000). Minority Rules: The Miao and the Feminine in China's Cultural Politics (illustrated, reprint ed.). Duke University Press. p. 85. ISBN 082232444X. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ http://www.hmongarchives.org/

- ↑ http://www.3us.com/viewthread.php?tid=55204

- ↑ Ramsey, S. Robert (1987). The Languages of China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 284. ISBN 069101468X. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Tanya Storch Religions and missionaries around the Pacific, 1500-1900 2006 p293

- ↑ 苗文创制与苗语方言划分的历史回顾

Other branches had been left unclassified. - 1 2 Strecker, David (1987). "The Hmong-Mien Languages" (PDF). Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 10 (2): 1–11.

- ↑ Strecker, David. (1987). "Some comments on Benedict's 'Miao-Yao enigma: the Na-e language'" (PDF). Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 10 (2): 22–42.

- ↑ 王士元、邓晓华,《苗瑶语族语言亲缘关系的计量研究——词源统计分析方法》,《中国语文》,2003(294)。

- ↑ Matisoff, 2006. "Genetic versus Contact Relationship". In Aikhenvald & Dixon, Areal diffusion and genetic inheritance

- ↑ Ratliff, Martha. 2010. Hmong–Mien language history. Canberra, Australia: Pacific Linguistics.

- ↑ 毛宗武, 李云兵 / Mao Zongwu, Li Yunbing. 1997. 巴哼语研究 / Baheng yu yan jiu (A Study of Baheng [Pa-Hng]). Shanghai: 上海远东出版社 / Shanghai yuan dong chu ban she.

- ↑ Yoshihisa Taguchi [田口善久] (2012). On the Phylogeny of the Hmong-Mien languages. Conference in Evolutionary Linguistics 2012.

- ↑ http://asiaharvest.org/wp-content/themes/asia/docs/people-groups/China/chinaPeoples/L/Laba.pdf

- ↑ http://asiaharvest.org/wp-content/themes/asia/docs/people-groups/China/chinaPeoples/M/MiaoBaishi.pdf

- ↑ http://lingweb.eva.mpg.de/numeral/Miao-Yao.htm

- 1 2 ɿ is commonly used by Sinologists to mean [ɨ].

External links

- Li Jinping, Li Tianyi [李锦平, 李天翼]. 2012. A comparative study of Miao dialects [苗语方言比较研究]. Chengdu: Southwest Jiaotong University Press.

- 283-word wordlist recording in Wuding Maojie Hmong (Dianxi Miao) dialect (F, 31), ellicited in Standard Mandarin, archived with Kaipuleohone.