Dynamics (music)

In music, the dynamics of a piece is the variation in loudness between notes or phrases. Dynamics are indicated by specific musical notation, often in some detail. However, dynamics markings still require interpretation by the performer depending on the musical context: for instance a piano (quiet) marking in one part of a piece might have quite different objective loudness in another piece, or even a different section of the same piece. The execution of dynamics also extends beyond loudness to include changes in timbre and sometimes tempo rubato.

Purpose and Interpretation

Dynamics are one of the expressive elements of music. Used effectively, dynamics help musicians sustain variety and interest in a musical performance, and communicate a particular emotional state or feeling.

Dynamic markings are always relative.[1] p never indicates a precise level of loudness, it merely indicates that music in a passage so marked should be considerably quieter than f. There are many factors affecting the interpretation of a dynamic marking. For instance, the middle of a musical phrase will normally be played louder than the beginning or ending, to ensure the phrase is properly shaped, even where a passage is marked p throughout. Similarly, in multi-part music, some voices will naturally be played louder than others, for instance to emphasis the melody and the bass line, even if a whole passage is marked at one dynamic level. Some instruments are naturally louder than others - for instance, a tuba playing piano will likely be louder than a guitar playing fortissimo, while a high-pitched instrument piccolo playing in its upper register can usually sound loud even where its actual decibel level is lower than that of other instruments.

Further, a dynamic marking does not necessarily only affect loudness of the music. A forte passage is not usually "the same as a piano passage but louder". Rather, a musician will often use a different approach to other aspects of expression like timbre or articulation to further illustrate the differences. Sometimes this might also extend to tempo. It's important for a performer to be able to control dynamics and tempo independently, and thus novice musicians are often instructed "don't speed up just because it's getting louder!". However, in some circumstances, a dynamic marking might also indicate a change of tempo.[2]

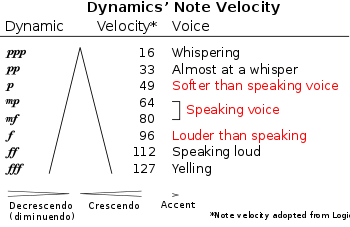

In some music notation programs, there are default MIDI key velocity values associated with these indications, but more sophisticated programs allow users to change these as needed. Apple's Logic Pro 9 uses the following values: ppp (16), pp (32), p (48), mp (64), mf (80), f (96), ff (112), fff (127).[3]

Dynamic markings

The two basic dynamic indications in music are:

More subtle degrees of loudness or softness are indicated by:

- mp, standing for mezzo-piano, meaning "half soft".

- mf, standing for mezzo-forte, meaning "half loud".[7]

- più p, standing for più piano and meaning "softer".

- più f, standing for più forte and meaning "louder".

Use of up to three consecutive fs or ps is also common:

- pp, standing for pianissimo and meaning "very soft".

- ff, standing for fortissimo and meaning "very loud".

- ppp, standing for pianississimo and meaning "very very soft" (or alternatively pianissimo possibile, "as soft as possible").

- fff, standing for fortississimo and meaning "very very loud".[7]

The overall ranking of these is:

ppp pp più p p mp mf f più f ff fff softest loudest

Changes

Three Italian words are used to show gradual changes in volume:

- crescendo (abbreviated cresc.) translates as "increasing" (literally "growing").

- decrescendo (abbreviated to decresc.) translates as "decreasing".

- diminuendo (abbreviated dim.) translates as "diminishing".

Signs sometimes referred to as "hairpins"[8] are also used to stand for these words (See image). If the angle lines open up (![]() ), then the indication is to get louder; if they close gradually (

), then the indication is to get louder; if they close gradually (![]() ), the indication is to get softer. The following notation indicates music starting moderately strong, then becoming gradually stronger and then gradually quieter:

), the indication is to get softer. The following notation indicates music starting moderately strong, then becoming gradually stronger and then gradually quieter:

Hairpins are usually written below the staff (or between the two staves in a grand staff), but are sometimes found above, especially in music for singers or in music with multiple melody lines being played by a single performer. They tend to be used for dynamic changes over a relatively short space of time (at most a few bars), while cresc., decresc. and dim. are generally used for changes over a longer period. Word directions can be extended with dashes to indicate over what time the event should occur, which may be as long as multiple pages.

For greater changes in dynamics, cresc. molto and dim. molto are often used, where the molto means "much". Similarly, for more gradual changes poco cresc. and poco dim. are used, where "poco" translates as a little, or alternatively with poco a poco meaning "little by little. Sudden changes in dynamics may be notated by adding the word subito (meaning "suddenly") as a prefix or suffix to the new dynamic notation.

Accented notes can be notated sforzando, sforzato, forzando or forzato (abbreviated sfz, sf, or fz) ("forcing" or "forced"), or using the sign >, placed above or below the head of the note.

Sforzando (or sforzato, forzando, forzato) indicates a forceful accent and is abbreviated as sf, sfz or fz. There is often confusion surrounding these markings and whether or not there is any difference in the degree of accent. However, all of these indicate the same expression, depending on the dynamic level,[9] and the extent of the sforzando is determined purely by the performer.

The fortepiano notation fp indicates a forte followed immediately by piano. By contrast, pf is an abbreviation for poco forte, literally "a little loud" but (according to Brahms) meaning with the character of forte, but the sound of piano, though rarely used because of possible confusion with pianoforte).[10]

Extreme dynamic markings

While the typical range of dynamic markings is from ppp to fff, some pieces use additional markings of further emphasis. This kind of usage is most common in orchestral works from the late 19th-century onwards. Generally, these markings are supported by the orchestration of the work, with heavy forte markings brought to life by having many loud instruments like brass and percussion playing at once. For instance, in Holst's The Planets, ffff occurs twice in "Mars" and once in "Uranus", often punctuated by organ. It also appears in Heitor Villa-Lobos' Bachianas Brasileiras No. 4 (Prelude), and in Liszt's Fantasy and Fugue on the chorale "Ad nos, ad salutarem undam". The Norman Dello Joio Suite for Piano ends with a crescendo to a ffff, and Tchaikovsky indicated a bassoon solo pppppp (6 p) in his Pathétique Symphony and ffff in passages of his 1812 Overture and the 2nd movement of his Fifth Symphony.

Igor Stravinsky used ffff at the end of the finale of the Firebird Suite. ffff is also found in a prelude by Rachmaninoff, op.3-2. Shostakovich even went as loud as fffff (5 fs) in his fourth symphony. Gustav Mahler, in the third movement of his Seventh Symphony, gives the celli and basses a marking of fffff (5 fs), along with a footnote directing 'pluck so hard that the strings hit the wood'. On the other extreme, Carl Nielsen, in the second movement of his Symphony No. 5, marked a passage for woodwinds a diminuendo to ppppp (5 ps).

Another more extreme dynamic is in György Ligeti's Études No. 13 (Devil's Staircase), which has at one point a ffffff (6 fs) and progresses to a ffffffff (8 fs). In Ligeti's Études No. 9, he uses pppppppp (8 ps). In the baritone passage "Era la notte" from his opera Otello, Verdi uses pppp. In the full score the same spot is marked ppp.[11] Steane (1971) and others suggest that such markings are in reality a strong reminder to less than subtle singers to at least sing softly rather than an instruction to the singer actually to attempt a pppp.

History

On Music, one of the ''Moralia'' attributed to the philosopher Plutarch in the first century AD, suggests that ancient Greek musical performance included dynamic transitions - though dynamics receive far less attention in the text than does rhythm or harmony.

The Renaissance composer Giovanni Gabrieli was one of the first to indicate dynamics in music notation, but dynamics were used sparingly by composers until the late 18th century. Bach used some dynamic terms, including forte, piano, più piano, and pianissimo (although written out as full words), and in some cases it may be that ppp was considered to mean pianissimo in this period.

The fact that the harpsichord could play only "terraced" dynamics (either loud or soft, but not in between), and the fact that composers of the period did not mark gradations of dynamics in their scores, has led to the "somewhat misleading suggestion that baroque dynamics are 'terraced dynamics'," writes Robert Donington.[12] In fact, baroque musicians constantly varied dynamics. "Light and shade must be constantly introduced... by the incessant interchange of loud and soft," wrote Johann Joachim Quantz in 1752.[13] In addition to this, the harpsichord in fact becomes louder or softer depending on the thickness of the musical texture (four notes are louder than two). This allowed composers such as Bach to build dynamics directly into their compositions, without the need for notation.

In the Romantic period, composers greatly expanded the vocabulary for describing dynamic changes in their scores. Where Haydn and Mozart specified six levels (pp to ff), Beethoven used also ppp and fff (the latter less frequently), and Brahms used a range of terms to describe the dynamics he wanted. In the slow movement of the trio for violin, horn and piano (Opus 40), he uses the expressions ppp, molto piano, and quasi niente to express different qualities of quiet. Many Romantic and later composers added più p and più f, making for a total of ten levels between ppp and fff.

See also

| Look up fortissimo or decrescendo in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

References

- ↑ Thiemel, Matthias. "Dynamics". Grove Music Online (subscriber only access). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ For instance, in Schubert's string quartet Death and the Maiden, the dimenuendo marking is followed by a tempo, indicating that the dimenuendo is a reduction in speed as well as in loudness. In the same work Schubert uses decrescendo to indicate a reduction in loudness with no change in speed.

- ↑ "Apple Logic Pro 9 User Manual for MIDI Step Input Recording". Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- 1 2 Randel, Don Michael (2003). The Harvard Dictionary of Music (4th ed.). Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press Reference Library.

- ↑ "Piano". Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Forte". Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- 1 2 "Dynamics". Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ Kennedy, Michael and Bourne, Joyce: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music (1996), entry "Hairpins".

- ↑ Gerou, Tom; Lusk, Linda (1996). Essential Dictionary of Music Notation: The Most Practical and Concise Source for Music Notation. Van Nuys, CA: Alfred Music Publishing. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0882847306.

- ↑ An Enigmatic Marking Explained, by Jeffrey Solow, Violoncello Society Newsletter, Spring 2000

- ↑ (1965). The Musical Times, Vol. 106. Novello.

- ↑ Donington, Robert: Baroque Music (1982) WW Norton, 1982. ISBN 0-393-30052-8. Page 32.

- ↑ Donington, Robert: Baroque Music (1982) WW Norton, 1982. ISBN 0-393-30052-8. Page 33.