Metropolitan Railway

The Metropolitan Railway (also known as the Met[note 1]) was a passenger and goods railway that served London from 1863 to 1933, its main line heading north-west from the capital's financial heart in the City to what were to become the Middlesex suburbs. Its first line connected the main-line railway termini at Paddington, Euston, and King's Cross to the City. The first section was built beneath the New Road using the "cut-and-cover" method between Paddington and King's Cross and in tunnel and cuttings beside Farringdon Road from King's Cross to near Smithfield, near the City. It opened to the public on 10 January 1863 with gas-lit wooden carriages hauled by steam locomotives, the world's first passenger-carrying designated underground railway.[2]

The line was soon extended from both ends, and northwards via a branch from Baker Street. It reached Hammersmith in 1864, Richmond in 1877 and completed the Inner Circle in 1884, but the most important route was the line north into the Middlesex countryside, where it stimulated the development of new suburbs. Harrow was reached in 1880, and the line eventually extended to Verney Junction in Buckinghamshire, more than 50 miles (80 kilometres) from Baker Street and the centre of London.

Electric traction was introduced in 1905 and by 1907 electric multiple units operated most of the services, though electrification of outlying sections did not occur until decades later. Unlike other railway companies in the London area, the Met developed land for housing, and after World War I promoted housing estates near the railway using the "Metro-land" brand. On 1 July 1933, the Met was amalgamated with the Underground Electric Railways Company of London and the capital's tramway and bus operators to form the London Passenger Transport Board.

Former Met tracks and stations are used by the London Underground's Metropolitan, Circle, District, Hammersmith & City, Piccadilly, and Jubilee lines, and by Chiltern Railways.

History

Paddington to the City, 1853–63

Establishment

In the first half of the 19th century the population and physical extent of London grew greatly.[note 2] The increasing resident population and the development of a commuting population arriving by train each day led to a high level of traffic congestion with huge numbers of carts, cabs, and omnibuses filling the roads and up to 200,000 people entering the City of London, the commercial heart, each day on foot.[4] By 1850 there were seven railway termini around the urban centre of London: London Bridge and Waterloo to the south, Shoreditch and Fenchurch Street to the east, Euston and King's Cross to the north, and Paddington to the west. Only Fenchurch Street station was within the City.[5]

The congested streets and the distance to the City from the stations to the north and west prompted many attempts to get parliamentary approval to build new railway lines into the City. None were successful, and the 1846 Royal Commission investigation into Metropolitan Railway Termini banned construction of new lines or stations in the built-up central area.[6][7][note 3] The concept of an underground railway linking the City with the mainline termini was first proposed in the 1830s. Charles Pearson, Solicitor to the City, was a leading promoter of several schemes and in 1846 proposed a central railway station to be used by multiple railway companies.[8] The scheme was rejected by the 1846 commission, but Pearson returned to the idea in 1852 when he helped set up the City Terminus Company to build a railway from Farringdon to King's Cross. Although the plan was supported by the City, the railway companies were not interested and the company struggled to proceed.[9]

The Bayswater, Paddington, and Holborn Bridge Railway Company was established to connect the Great Western Railway's (GWR's) Paddington station to Pearson's route at King's Cross.[9][note 4] A bill was published in November 1852[10] and in January 1853 the directors held their first meeting and appointed John Fowler as its engineer.[11] After successful lobbying, the company secured parliamentary approval under the name of the "North Metropolitan Railway" in the summer of 1853. The bill submitted by the City Terminus Company was rejected by Parliament, which meant that the North Metropolitan Railway would not be able to reach the City: to overcome this obstacle, the company took over the City Terminus Company and submitted a new bill in November 1853. This dropped the City terminus and extended the route south from Farringdon to the General Post Office in St. Martin's Le Grand. The route at the western end was also altered so that it connected more directly to the GWR station. Permission was also sought to connect to the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) at Euston and to the Great Northern Railway (GNR) at King's Cross, the latter by hoists and lifts.[12] The company's name was also to be changed again, to Metropolitan Railway.[9][13] Royal assent was granted to the North Metropolitan Railway Act on 7 August 1854.[12][14]

Construction of the railway was estimated to cost £1 million. Initially, with the Crimean War under way, the Met found it hard to raise the capital.[9] While it attempted to raise the funds it presented new bills to Parliament seeking an extension of time to carry out the works.[12][note 5] In July 1855, an Act to make a direct connection to the GNR at King's Cross received royal assent. The plan was modified in 1856 by the Metropolitan (Great Northern Branch and Amendment) Act and in 1860 by the Great Northern & Metropolitan Junction Railway Act.[12]

Although the GWR agreed to contribute £175,000 and a similar sum was promised by the GNR, sufficient funds to make a start on construction had not been raised by the end of 1857. Costs were reduced by cutting back part of the route at the western end so that it did not connect directly to the GWR station, and by dropping the line south of Farringdon.[15][note 6] In 1858, Pearson arranged a deal between the Met and the City of London Corporation whereby the Met bought land it needed around the new Farringdon Road from the City for £179,000 and the City purchased £200,000 worth of shares.[17][note 7] The route changes were approved by Parliament in August 1859, meaning that the Met finally had the funding to match its obligations and construction could begin.[18]

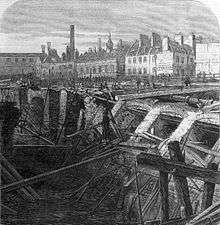

Construction

Despite concerns about undermining and vibrations causing subsidence of nearby buildings[19] and compensating the thousands of people whose homes were destroyed during the digging of the tunnel[20] construction began in March 1860.[16] The line was mostly built using the "cut-and-cover" method from Paddington to King's Cross; east of there it continued in a 728 yards (666 m) tunnel under Mount Pleasant, Clerkenwell then followed the culverted River Fleet beside Farringdon Road in an open cutting to near the new meat market at Smithfield.[21][22]

The trench was 33 feet 6 inches (10.2 m) wide, with brick retaining walls supporting an elliptical brick arch or iron girders spanning 28 feet 6 inches (8.7 m).[23] The tunnels were wider at stations to accommodate the platforms. Most of the excavation work was carried out manually by navvies, although a primitive earth-moving conveyor was used to remove excavated spoil from the trench.[24][note 8]

Within the tunnel, two lines were laid with a 6-foot (1.8 m) gap between. To accommodate both the standard gauge trains of the GNR and the broad gauge trains of the GWR, the track was three-rail mixed gauge, the rail nearest the platforms being shared by both gauges.[16] Signalling was on the absolute block method, using electric Spagnoletti block instruments and fixed signals.[25]

Construction was not without incident. In May 1860, a GNR train overshot the platform at King's Cross and fell into the workings. Later in 1860, a boiler explosion on an engine pulling contractor's wagons killed the driver and his assistant. In May 1861, the excavation collapsed at Euston causing considerable damage to the neighbouring buildings. The final accident occurred in June 1862 when the Fleet sewer burst following a heavy rainstorm and flooded the excavations. The Met and the Metropolitan Board of Works managed to stem and divert the water and the construction was delayed by only a few months.[26]

Trial runs were carried out from November 1861 while construction was still under way. The first trip over the whole line was in May 1862 with William Gladstone among the guests.[27] By the end of 1862 work was complete at a cost of £1.3 million.[28][note 9]

Opening

Board of Trade inspections took place in late December 1862 and early January 1863 to approve the railway for opening.[30] After minor signalling changes were made, approval was granted and a few days of operating trials were carried out before the grand opening on 9 January 1863, which included a ceremonial run from Paddington and a large banquet for 600 shareholders and guests at Farringdon.[30] Charles Pearson did not live to see the completion of the project; he died in September 1862.[31]

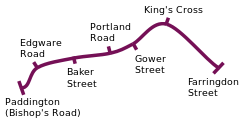

The 3.75-mile (6 km) railway opened to the public on Saturday 10 January 1863.[29] There were stations at Paddington (Bishop's Road) (now Paddington), Edgware Road, Baker Street, Portland Road (now Great Portland Street), Gower Street (now Euston Square), King's Cross (now King's Cross St Pancras), and Farringdon Street (now Farringdon).[32]

The railway was hailed a success, carrying 38,000 passengers on the opening day, using GNR trains to supplement the service.[33] In the first 12 months 9.5 million passengers were carried[22] and in the second 12 months this increased to 12 million.[34]

The original timetable allowed 18 minutes for the journey. Off-peak service frequency was every 15 minutes, increased to ten minutes during the morning peak and reduced 20 minutes in the early mornings and after 8 pm. From May 1864, workmen's returns were offered on the 5:30 am and 5:40 am services from Paddington at the cost of a single ticket (3d).[35]

Initially the railway was worked by GWR broad-gauge Metropolitan Class steam locomotives and rolling stock. Soon after the opening disagreement arose between the Met and the GWR over the need to increase the frequency, and the GWR withdrew its stock in August 1863. The Met continued operating a reduced service using GNR standard-gauge rolling stock before purchasing its own standard-gauge locomotives from Beyer, Peacock and rolling stock.[31][36][note 10]

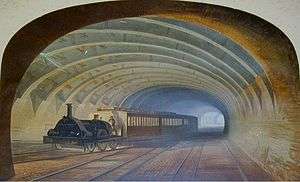

The Metropolitan initially ordered 18 tank locomotives, of which a key feature was condensing equipment which prevented most of the steam from escaping while trains were in tunnels; they have been described as "beautiful little engines, painted green and distinguished particularly by their enormous external cylinders."[38] The design proved so successful that eventually 120 were built to provide traction on the Metropolitan, the District Railway (in 1871) and all other 'cut and cover' underground lines.[38] This 4-4-0 tank engine can therefore be considered as the pioneer motive power on London's first underground railway;[39] ultimately, 148 were built between 1864 and 1886 for various railways, and most kept running until electrification in 1905.

In the belief that it would be operated by smokeless locomotives, the line had been built with little ventilation and a long tunnel between Edgware Road and King's Cross.[40] Initially the smoke-filled stations and carriages did not deter passengers[41] and the ventilation was later improved by making an opening in the tunnel between Gower Street and King's Cross and removing glazing in the station roofs.[42] With the problem continuing after the 1880s, conflict arose between the Met, who wished to make more openings in the tunnels, and the local authorities, who argued that these would frighten horses and reduce property values.[43] This led to an 1897 Board of Trade report,[note 11] which reported that a pharmacist was treating people in distress after having travelled on the railway with his 'Metropolitan Mixture'. The report recommended more openings be authorised but the line was electrified before these were built.[43]

Extensions and the Inner Circle, 1863–84

Farringdon to Moorgate and the City Widened Lines

.svg.png)

With connections to the GWR and GNR under construction and connections to the Midland Railway and London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LC&DR) planned, the Met obtained permission in 1861 and 1864[note 12] for two additional tracks from King's Cross to Farringdon Street and a four-track eastward extension to Moorgate.[45][46][47] The Met used two tracks: the other two tracks, the City Widened Lines, used mainly by other railway companies.[48]

A pair of single-track tunnels at King's Cross connecting the GNR to the Met opened on 1 October 1863 when the GNR began running services,[49][note 13] the GWR returning the same day with through suburban trains from such places as Windsor.[50] By early autumn 1864 the Met had sufficient carriages and locomotives to run its own trains and increase the frequency to six trains an hour.[51]

On 1 January 1866, LC&DR and GNR joint services from Blackfriars Bridge began operating via the Snow Hill tunnel under Smithfield market to Farringdon and northwards to the GNR.[52] The extension to Aldersgate Street and Moorgate Street (now Barbican and Moorgate) had opened on 23 December 1865[53] and all four tracks were open on 1 March 1866.[54]

The new tracks from King's Cross to Farringdon were first used by a GNR freight train on 27 January 1868. The Midland Railway junction opened on 13 July 1868 when services ran into Moorgate Street before its St Pancras terminus had opened. The line left the main line at St Paul's Road Junction, entering a double-track tunnel and joining the Widened Lines at Midland Junction.[55]

Hammersmith & City Railway

.svg.png)

In November 1860, a bill was presented to Parliament,[note 14] supported by the Met and the GWR, for a railway from the GWR's main line a mile west of Paddington to the developing suburbs of Shepherd's Bush and Hammersmith, with a connection to the West London Railway at Latimer Road.[57][58] Authorised on 22 July 1861 as the Hammersmith and City Railway (H&CR),[59] the 2 miles 35 chains (3.9 km) line, constructed on a 20-foot (6.1 m) high viaduct largely across open fields,[60] opened on 13 June 1864 with a broad-gauge GWR service from Farringdon Street, [61] with stations at Notting Hill (now Ladbroke Grove), Shepherd's Bush (replaced by the current Shepherd's Bush Market in 1914) and Hammersmith.[32] The link to the West London Railway opened on 1 July that year, served by a carriage that was attached or detached at Notting Hill for Kensington (Addison Road).[61] Following an agreement between the Met and the GWR, from 1865 the Met ran a standard-gauge service to Hammersmith and the GWR a broad-gauge service to Kensington. In 1867, the H&CR became jointly owned by the two companies. The GWR began running standard-gauge trains and the broad gauge rail was removed from the H&CR and the Met in 1869. In 1871, two additional tracks parallel to the GWR between Westbourne Park and Paddington were brought into use for the H&CR and in 1878 the flat crossing at Westbourne Park was replaced by a diveunder.[60] In August 1872, the GWR Addison Road service was extended over the District Railway via Earl's Court to Mansion House. This became known as the Middle Circle and ran until January 1905, although from 1 July 1900 trains terminated at Earl's Court.[62] Additional stations were opened at Westbourne Park (1866), Latimer Road (1868), Royal Oak (1871), Wood Lane (1908) and Goldhawk Road (1914).

Between 1 October 1877 and 31 December 1906 some services on the H&CR were extended to Richmond over the London and South Western Railway (L&SWR) via its station at Hammersmith (Grove Road).[63][note 15]

Inner Circle

The early success of the Met prompted a flurry of applications to Parliament in 1863 for new railways in London, many of them competing for similar routes. To consider the best proposals, the House of Lords established a select committee, which issued a report in July 1863 with a recommendation for an "inner circuit of railway that should abut, if not actually join, nearly all of the principal railway termini in the Metropolis". A number of railway schemes were presented for the 1864 parliamentary session that met the recommendation in varying ways and a joint committee composed of members of both Houses of Parliament was set up to review the options.[64][note 16]

Proposals from the Met to extend south from Paddington to South Kensington and east from Moorgate to Tower Hill were accepted and received royal assent on 29 July 1864.[66] To complete the circuit, the committee encouraged the amalgamation of two schemes via different routes between Kensington and the City, and a combined proposal under the name Metropolitan District Railway (commonly known as the District railway) was agreed on the same day.[66][67][note 17] Initially, the District and the Met were closely associated and it was intended that they would soon merge. The Met's chairman and three other directors were on the board of the District, John Fowler was the engineer of both companies and the construction works for all of the extensions were let as a single contract.[68][69] The District was established as a separate company to enable funds to be raised independently of the Met.[68]

Starting as a branch from Praed Street junction, a short distance east of the Met's Paddington station, the western extension passed through fashionable districts in Bayswater, Notting Hill, and Kensington. Land values here were higher and, unlike the original line, the route did not follow an easy alignment under existing roads. Compensation payments for property were much higher. In Leinster Gardens, Bayswater, a façade of two five-storey houses was built at Nos. 23 and 24 to conceal the gap in a terrace created by the railway passing through. To ensure adequate ventilation, most of the line was in cutting except for a 421-yard (385 m) tunnel under Campden Hill.[70] Construction of the District proceeded in parallel with the work on the Met and it too passed through expensive areas. Construction costs and compensation payments were so high that the cost of the first section of the District from South Kensington to Westminster was £3 million, almost three times as much as the Met's original, longer line.[71]

The first section of the Met extension opened to Brompton (Gloucester Road) (now Gloucester Road) on 1 October 1868,[68] with stations at Paddington (Praed Street) (now Paddington), Bayswater, Notting Hill Gate, and Kensington (High Street) (now High Street Kensington).[32] Three months later, on 24 December 1868, the Met extended eastwards to a shared station at South Kensington and the District opened its line from there to Westminster, with other stations at Sloane Square, Victoria, St James's Park, and Westminster Bridge (now Westminster).[32]

The District also had parliamentary permission to extend westward from Brompton and, on 12 April 1869, it opened a single-track line to West Brompton on the WLR. There were no intermediate stations and at first this service operated as a shuttle.[72][73] By summer 1869 separate tracks had been laid between South Kensington and Brompton and from Kensington (High Street) to a junction with the line to West Brompton. During the night of 5 July 1870 the District secretly built the disputed Cromwell curve connecting Brompton and Kensington (High Street).[74]

East of Westminster, the next section of the District's line ran in the new Victoria Embankment built by the Metropolitan Board of Works along the north bank of the River Thames. The line opened from Westminster to Blackfriars on 30 May 1870[72] with stations at Charing Cross (now Embankment), The Temple (now Temple) and Blackfriars.[32]

On its opening the Met operated the trains on the District, receiving 55 per cent of the gross receipts for a fixed level of service. Extra trains required by the District were charged for and the District's share of the income dropped to about 40 per cent. The District's level of debt meant that the merger was no longer attractive to the Met and did not proceed, so the Met's directors resigned from the District's board. To improve its finances, the District gave the Met notice to terminate the operating agreement. Struggling under the burden of its very high construction costs, the District was unable to continue with the remainder of the original scheme to reach Tower Hill and made a final extension of its line just one station east from Blackfriars to a previously unplanned City terminus at Mansion House.[75][76]

.svg.png)

On Saturday 1 July 1871 an opening banquet was attended by Prime Minister William Gladstone, who was also a shareholder. The following Monday, Mansion House opened and the District began running its own trains.[77] From this date, the two companies operated a joint Inner Circle service between Mansion House and Moorgate Street via South Kensington and Edgware Road every ten minutes,[note 18] supplemented by a District service every ten minutes between Mansion House and West Brompton and H&CR and GWR suburban services between Edgware Road and Moorgate Street.[78] The permissions for the railway east of Mansion House were allowed to lapse.[79] At the other end of the line, the District part of South Kensington station opened on 10 July 1871 [80][note 19] and Earl's Court station opened on the West Brompton extension on 30 October 1871.[32]

In 1868 and 1869, judgements went against the Met in a number of hearings, finding financial irregularities such as the company paying a dividend it could not afford and expenses being paid out of the capital account. In 1870, its directors were found guilty of a breach of trust and ordered to compensate the company.[82] Although they all appealed and were allowed in 1874 to settle for a much lower amount,[83] to restore shareholders' confidence the directors had all been replaced by October 1872 and Edward Watkin appointed chairman.[84] Watkin was an experienced railwayman and already on the board of several railway companies, including the South Eastern Railway (SER), and had an aspiration to construct a line from the north through London to that railway.[85][note 20]

Due to the cost of land purchases, the Met's eastward extension from Moorgate Street was slow to progress and it had to obtain an extension of the Act's time limit in 1869. The extension was begun in 1873, but after construction exposed burials in the vault of a Roman Catholic chapel, the contractor reported that it was difficult to keep the men at work. The first section opened to the Great Eastern Railway's (GER's) recently opened terminus at Liverpool Street on 1 February 1875. For a short time, while the Met's station was being built, services ran into the GER station via a 3.5-chain (70 m) curve, the Met opening its station later that year on 12 July and this curve not being used again by regular traffic. During the extension of the railway to Aldgate several hundred cartloads of bullocks' horn were discovered in a layer 20 ft (6.1 m) below the surface. A terminus opened at Aldgate on 18 November 1876, initially for a shuttle service to Bishopsgate before all Met and District trains worked through from 4 December.[88]

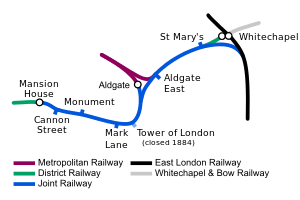

Conflict between the Met and the District and the expense of construction delayed further progress on the completion of the inner circle. In 1874, frustrated City financiers formed the Metropolitan Inner Circle Completion Railway Company with the aim of finishing the route. This company was supported by the District and obtained parliamentary authority on 7 August 1874.[90][91] The company struggled to raise the funding and an extension of time was granted in 1876.[90] A meeting between the Met and the District was held in 1877 with the Met now wishing to access the SER via the East London Railway (ELR). Both companies promoted and obtained an Act of Parliament in 1879 for the extension and link to the ELR, the Act also ensuring future co-operation by allowing both companies access to the whole circle.[note 21] A large contribution was made by authorities for substantial road and sewer improvements. In 1882, the Met extended its line from Aldgate to a temporary station at Tower of London.[93] Two contracts to build joint lines were placed, from Mansion House to the Tower in 1882 and from the circle north of Aldgate to Whitechapel with a curve onto the ELR in 1883. From 1 October 1884, the District and the Met began working trains from St Mary's via this curve onto the ELR to the SER's New Cross station.[94][note 22] After an official opening ceremony on 17 September and trial running a circular service started on Monday 6 October 1884. On the same day the Met extended some H&CR services over the ELR to New Cross, calling at new joint stations at Aldgate East and St Mary's.[94][32] Joint stations opened on the circle line at Cannon Street, Eastcheap (Monument from 1 November 1884) and Mark Lane. The Met's Tower of London station closed on 12 October 1884 after the District refused to sell tickets to the station.[95] Initially, the service was eight trains an hour, completing the 13 miles (21 kilometres) circle in 81–84 minutes, but this proved impossible to maintain and was reduced to six trains an hour with a 70-minute timing in 1885. Guards were permitted no relief breaks during their shift until September 1885, when they were permitted three 20-minute breaks.[96]

Extension Line, 1868–99

Baker Street to Harrow

| Metropolitan Railway Extension Line | |

|---|---|

|

Railway transferred to LPTB in 1933 |

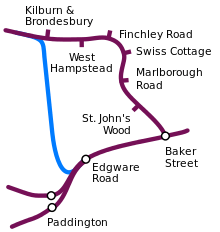

In April 1868, the Metropolitan & St John's Wood Railway (M&SJWR) opened a single-track railway in tunnel to Swiss Cottage from new platforms at Baker Street (called Baker Street East).[97][98] There were intermediate stations at St John's Wood Road and Marlborough Road, both with crossing loops, and the line was worked by the Met with a train every 20 minutes. A junction was built with the Inner Circle at Baker Street, but there were no through trains after 1869.[99]

The original intention of the Metropolitan & St. John's Wood Railway was to run to underground north-east to Hampstead Village, and indeed this appeared on some maps.[100] Although in the event this was not completed in full and the line was built in a north-western direction instead, a short heading of tunnel was built north of Swiss Cottage station in the direction of Hampstead.[101] This is still visible today when traveling on a southbound Metropolitan line service.

In the early 1870s, passenger numbers were low and the M&SJWR was looking to extend the line to generate new traffic. Recently placed in charge of the Met, Watkin saw this as the priority as the cost of construction would be lower than in built-up areas and fares higher; traffic would also be fed into the Circle.[102][103] In 1873, the M&SJWR was given authority to reach the Middlesex countryside at Neasden,[104][note 23] but as the nearest inhabited place to Neasden was Harrow it was decided to build the line 3.5 miles (5.6 km) further to Harrow[105] and permission was granted in 1874.[104][note 24] To serve the Royal Agricultural Society's 1879 show at Kilburn, a single line to West Hampstead opened on 30 June 1879 with a temporary platform at Finchley Road. Double track and a full service to Willesden Green started on 24 November 1879 with a station at Kilburn & Brondesbury (now Kilburn).[106] The line was extended 5 miles 37.5 chains (8.80 km) to Harrow, the service from Baker Street beginning on 2 August 1880. The intermediate station at Kingsbury Neasden (now Neasden) was opened the same day.[107] Two years later, the single-track tunnel between Baker Street and Swiss Cottage was duplicated and the M&SJWR was absorbed by the Met.[108]

In 1882, the Met moved its carriage works from Edgware Road to Neasden.[109] A locomotive works was opened in 1883 and a gas works in 1884. To accommodate employees moving from London over 100 cottages and ten shops were built for rent. In 1883, a school room and church took over two of the shops; two years later land was given to the Wesleyan Church for a church building and a school for 200 children.[110][note 25]

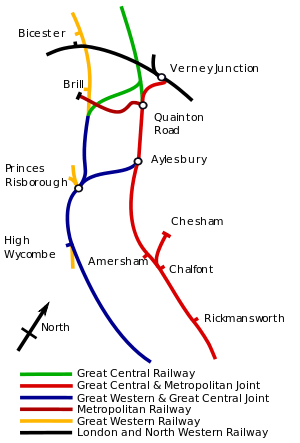

Harrow to Verney Junction and Brill

In 1868, the Duke of Buckingham opened the Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway (A&BR), a 12.75-mile (20.5 km) single track from Aylesbury to a new station at Verney Junction on the Buckinghamshire Railway's Bletchley to Oxford line.[113] At the beginning lukewarm support had been given by the LNWR, which worked the Bletchley to Oxford line, but by the time the line had been built the relationship between the two companies had collapsed.[note 26] The Wycombe Railway built a single-track railway from Princes Risborough to Aylesbury and when the GWR took over this company it ran shuttles from Princes Risborough through Aylesbury to Quainton Road and from Quainton Road to Verney Junction.[115]

The A&BR had authority for a southern extension to Rickmansworth, connecting with the LNWR's Watford and Rickmansworth Railway. Following discussions between the Duke and Watkin it was agreed that this line would be extended south to meet the Met at Harrow and permission for this extension was granted in 1874[104][note 27] and Watkin joined the board of the A&BR in 1875.[116] Money was not found for this scheme and the Met had to return to Parliament in 1880 and 1881 to obtain permission for a railway from Harrow to Aylesbury.[117][note 28] Pinner was reached in 1885 and an hourly service from Rickmansworth and Northwood to Baker Street started on 1 September 1887.[118] By then raising money was becoming very difficult although there was local support for a station at Chesham.[109] Authorised in 1885, double track from Rickmansworth was laid for 5 miles (8.0 km), then single to Chesham.[119] Services to Chesham calling at Chorley Wood and Chalfont Road (now Chalfont & Latimer) started on 8 July 1889.[120]

The Met took over the A&BR on 1 July 1891[120] and a temporary platform at Aylesbury opened on 1 September 1892 with trains calling at Amersham, Great Missenden, Wendover and Stoke Mandeville. In 1894, the Met and GWR joint station at Aylesbury opened.[121] Beyond Aylesbury to Verney Junction, the bridges were not strong enough for the Met's locomotives. The GWR refused to help, so locomotives were borrowed from the LNWR until two D Class locomotives were bought. The line was upgraded, doubled and the stations rebuilt to main-line standards,[122] allowing a through Baker Street to Verney Junction service from 1 January 1897, calling at a new station at Waddesdon Manor, a rebuilt Quainton Road, Granborough Road and Winslow Road.[32][123]

From Quainton Road, the Duke of Buckingham had built a 6.5-mile (10.5 km) branch railway, the Brill Tramway.[124] In 1899, there were four mixed passenger and goods trains each way between Brill and Quainton Road. There were suggestions of the Met buying the line and it took over operations in November 1899,[125] renting the line for £600 a year. The track was relaid and stations rebuilt in 1903. Passenger services were provided by A Class and D Class locomotives and Oldbury rigid eight-wheeled carriages.[126][127]

In 1893, a new station at Wembley Park was opened, initially used by the Old Westminsters Football Club, but primarily to serve a planned sports, leisure and exhibition centre.[128] A 1,159-foot (353 m) tower (higher than the recently built Eiffel Tower) was planned, but the attraction was not a success and only the 200-foot (61 m) tall first stage was built. The tower became known as "Watkin's Folly" and was dismantled in 1907 after it was found to be tilting.[129]

Around 1900, there were six stopping trains an hour between Willesden Green and Baker Street. One of these came from Rickmansworth and another from Harrow, the rest started at Willesden Green. There was also a train every two hours from Verney Junction, which stopped at all stations to Harrow, then Willesden Green and Baker Street. The timetable was arranged so that the fast train would leave Willesden Green just before a stopping service and arrived at Baker Street just behind the previous service.[130]

Great Central Railway

Watkin was also director of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR) and had plans for a 99-mile (159 km) London extension to join the Met just north of Aylesbury. There were suggestions that Baker Street could be used as the London terminus, but by 1891–2 the MS&LR had concluded it needed its own station and goods facilities in the Marylebone area. An Act for this railway was passed in 1893, but Watkin became ill and resigned his directorships in 1894. For a while after his departure the relationship between the companies turned sour.[87]

In 1895, the MS&LR put forward a bill to Parliament to build two tracks from Wembley Park to Canfield Place, near Finchley Road station, to allow its express trains to pass the Met's stopping service.[131] The Met protested before it was agreed that it would build the lines for the MS&LR's exclusive use.[132] When rebuilding bridges over the lines from Wembley Park to Harrow for the MS&LR, seeing a future need the Met quadrupled the line at the same time and the MS&LR requested exclusive use of two tracks.[133] The MS&LR had the necessary authority to connect to the Circle at Marylebone, but the Met suggested onerous terms. At the time the MS&LR was running short of money and abandoned the link.[134]

Because of the state of the relationship between the two companies the MS&LR was unhappy being wholly reliant on the Met for access to London and, unlike its railway to the north, south of Aylesbury there were several speed restrictions and long climbs, up to 1 in 90 in places. In 1898, the MS&LR and the GWR jointly presented a bill to Parliament for a railway (the Great Western and Great Central Joint Railway) with short connecting branches from Grendon Underwood, north of Quainton Road, to Ashendon and from Northolt to Neasden. The Met protested, claiming that the bill was 'incompatible with the spirit and terms' of the agreements between it and the MS&LR. The MS&LR was given authority to proceed, but the Met was given the right to compensation.[135] A temporary agreement was made to allow four MS&LR coal trains a day over the Met lines from 26 July 1898. The MS&LR wished these trains to also use the GWR route from Aylesbury via Princes Risborough into London, whereas the Met considered this was not covered by the agreement. A train scheduled to use the GWR route was not allowed access to the Met lines at Quainton Road in the early hours of 30 July 1898 and returned north. A subsequent court hearing found in the Met's favour, as it was a temporary arrangement.[136]

The MS&LR changed its name to the Great Central Railway (GCR) in 1897 and the Great Central Main Line from London Marylebone to Manchester Central opened for passenger traffic on 15 March 1899.[124] Negotiations about the line between the GCR and the Met took several years and in 1906 it was agreed that two tracks from Canfield Place to Harrow would be leased to the GCR for £20,000 a year and the Metropolitan and Great Central Joint Railway was created, leasing the line from Harrow to Verney Junction and the Brill branch for £44,000 a year, the GCR guaranteeing to place at least £45,000 of traffic on the line.[137] Aylesbury station, which had been jointly run by the GWR and the Met, was placed with a joint committee of the Great Western & Great Central and Metropolitan & Great Central Joint Committees, and generally known as Aylesbury Joint Station. The Met & GC Joint Committee took over the operation of the stations and line, but had no rolling stock. The Met provided the management and the GCR the accounts for the first five years before the companies switched functions, then alternating every five years until 1926. The Met maintained the line south of milepost 28.5 (south of Great Missenden), the GCR to the north.[138]

Electrification, 1900–14

Development

At the start of the 20th century, the District and the Met saw increased competition in central London from the new electric deep-level tube lines. With the opening in 1900 of the Central London Railway from Shepherd's Bush to the City with a flat fare of 2d, the District and the Met together lost four million passengers between the second half of 1899 and the second half of 1900.[139] The polluted atmosphere in the tunnels was becoming increasingly unpopular with passengers and conversion to electric traction was seen as the way forward.[140] Electrification had been considered by the Met as early as the 1880s, but such a method of traction was still in its infancy, and agreement would be needed with the District because of the shared ownership of the Inner Circle. A jointly owned train of six coaches ran an experimental passenger service on the Earl's Court to High Street Kensington section for six months in 1900. This was considered a success, tenders were requested and in 1901 a Met and District joint committee recommended the Ganz three-phase AC system with overhead wires.[141] This was accepted by both parties until the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) took control of the District. The UERL was led by the American Charles Yerkes, whose experience in the United States led him to favour DC with a third rail similar to that on the City & South London Railway and Central London Railway. After arbitration by the Board of Trade a DC system with four rails was taken up and the railways began electrifying using multiple-unit stock and electric locomotives hauling carriages.[142] In 1904, the Met opened a 10.5 MW coal-fired power station at Neasden, which supplied 11 kV 33.3 Hz current to five substations that converted this to 600 V DC using rotary converters.[143]

Meanwhile, the District had been building a line from Ealing to South Harrow and had authority for an extension to Uxbridge.[144] In 1899, the District had problems raising the finance and the Met offered a rescue package whereby it would build a branch from Harrow to Rayners Lane and take over the line to Uxbridge, with the District retaining running rights for up to three trains an hour.[145] The necessary Act was passed in 1899 and construction on the 7.5 miles (12.1 km) long branch started in September 1902, requiring 28 bridges and a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) long viaduct with 71 arches at Harrow. As this line was under construction it was included in the list of lines to be electrified, together with the railway from Baker Street to Harrow,[146] the inner circle and the joint GWR and Met H&C. The Met opened the line to Uxbridge on 30 June 1904 with one intermediate station at Ruislip, initially worked by steam.[144] Wooden platforms the length of three cars opened at Ickenham on 25 September 1905, followed by similar simple structures at Eastcote and Rayners Lane on 26 May 1906.[147]

Running electric trains

Electric multiple units began running on 1 January 1905 and by 20 March all local services between Baker Street and Harrow were electric.[148] The use of six-car trains was considered wasteful on the lightly used line to Uxbridge and in running an off-peak three-car shuttle to Harrow the Met aroused the displeasure of the Board of Trade for using a motor car to propel two trailers. A short steam train was used for off-peak services from the end of March while some trailers were modified to add a driving cab, entering service from 1 June.[147]

On 1 July 1905, the Met and the District both introduced electric units on the inner circle until later that day a Met multiple unit overturned the positive current rail on the District and the Met service was withdrawn. An incompatibility was found between the way the shoe-gear was mounted on Met trains and the District track and Met trains were withdrawn from the District and modified. Full electric service started on 24 September, reducing the travel time around the circle from 70 to 50 minutes.[149][150]

The GWR built a 6 MW power station at Park Royal and electrified the line between Paddington and Hammersmith and the branch from Latimer Road to Kensington (Addison Road). An electric service with jointly owned rolling stock started on the H&CR on 5 November 1906.[151] In the same year, the Met suspended running on the East London Railway, terminating instead at the District station at Whitechapel[32] until that line was electrified in 1913.[152] The H&CR service stopped running to Richmond over the L&SWR on 31 December 1906, although GWR steam rail motors ran from Ladbroke Grove to Richmond until 31 December 1910.[153]

The line beyond Harrow was not electrified so trains were hauled by an electric locomotive from Baker Street, changed for a steam locomotive en route.[142] From 1 January 1907, the exchange took place at Wembley Park.[154] From 19 July 1908, locomotives were changed at Harrow.[152] GWR rush hour services to the city continued to operate, electric traction taking over from steam at Paddington[155] from January 1907,[149] although freight services to Smithfield continued to be steam hauled throughout.[156][note 29]

In 1908, Robert Selbie[note 30] was appointed General Manager, a position he held until 1930.[160] In 1909, limited through services to the City restarted. Baker Street station was rebuilt with four tracks and two island platforms in 1912.[161] To cope with the rise in traffic the line south of Harrow was quadrupled, in 1913 from Finchley Road to Kilburn, in 1915 to Wembley Park;[162] the line from Finchley Road to Baker Street remained double track, causing a bottleneck.[163]

London Underground

To promote travel by the underground railways in London a joint marketing arrangement was agreed. In 1908, the Met joined this scheme, which included maps, joint publicity and through ticketing. UNDERGROUND signs were used outside stations in Central London. Eventually the UERL controlled all the underground railways except the Met and the Waterloo & City and introduced station name boards with a red disc and a blue bar. The Met responded with station boards with a red diamond and a blue bar.[164] Further coordination in the form of a General Managers' Conference faltered after Selbie withdrew in 1911 when the Central London Railway, without any reference to the conference, set its season ticket prices significantly lower than those on the Met's competitive routes.[165] Suggestions of merger with the Underground Group were rejected by Selbie, a press release of November 1912 noting the Met's interests in areas outside London, its relationships with main-line railways and its freight business.[166]

East London Railway

After the Met and the District had withdrawn from the ELR in 1906, services were provided by the South Eastern Railway, the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR) and the Great Eastern Railway. Both the Met and the District wanted to see the line electrified, but could not justify the whole cost themselves. Discussions continued, and in 1911 it was agreed that the ELR would be electrified with the UERL providing power and the Met the train service. Parliamentary powers were obtained in 1912 and through services restarted on 31 March 1913, the Met running two trains an hour from both the SER's and the LB&SCR's New Cross stations to South Kensington and eight shuttles an hour alternately from the New Cross stations to Shoreditch.[167][32]

Great Northern & City Railway

The Great Northern & City Railway (GN&CR) was planned to allow trains to run from the GNR line at Finsbury Park directly into the City at Moorgate. The tunnels were large enough to take a main-line train with an internal diameter of 16 feet (4.9 m), in contrast to those of the Central London Railway with a diameter less than 12 feet (3.7 m). The GNR eventually opposed the scheme, and the line opened in 1904 with the northern terminus in tunnels underneath GNR Finsbury Park station.[168]

Concerned that the GNR would divert its Moorgate services over the City Widened Lines to run via the GN&CR, the Met sought to take over the GN&CR. A bill was presented in 1912–13 to allow this with extensions to join the GN&CR to the inner circle between Moorgate and Liverpool Street and to the Waterloo & City line. The takeover was authorised, but the new railway works were removed from the bill after opposition from City property owners. The following year, a bill was jointly presented by the Met and GNR with amended plans that would have also allowed a connection between the GN&CR and GNR at Finsbury Park. Opposed, this time by the North London Railway, this bill was withdrawn.[169]

War and "Metro-land", 1914–32

World War I

On 28 July 1914 World War I broke out and on 5 August 1914 the Met was made subject to government control in the form of the Railway Executive Committee. It lost significant numbers of staff who volunteered for military service and from 1915 women were employed as booking clerks and ticket collectors.[170] The City Widened Lines assumed major strategic importance as a link between the channel ports and the main lines to the north, used by troop movements and freight. During the four years of war the line saw 26,047 military trains which carried 250,000 long tons (254,000 t) of materials,[171] although the sharp curves prevented ambulance trains returning with wounded using this route.[172] Government control was relinquished on 15 August 1921.[170]

Metro-land development

.png)

Unlike other railway companies, which were required to dispose of surplus land, the Met was in a privileged position with clauses in its acts allowing it to retain such land that it believed was necessary for future railway use.[note 31] Initially, the surplus land was managed by the Land Committee, made up of Met directors.[174] In the 1880s, at the same time as the railway was extending beyond Swiss Cottage and building the workers' estate at Neasden,[110] roads and sewers were built at Willesden Park Estate and the land was sold to builders. Similar developments followed at Cecil Park, near Pinner and, after the failure of the tower at Wembley, plots were sold at Wembley Park.[175][note 32]

In 1912, Selbie, then General Manager, thought that some professionalism was needed and suggested a company be formed to take over from the Surplus Lands Committee to develop estates near the railway.[178] World War I delayed these plans and it was 1919, with expectation of a housing boom,[179] before Metropolitan Railway Country Estates Limited (MRCE) was formed. Concerned that Parliament might reconsider the unique position the Met held, the railway company sought legal advice, which was that although the Met had authority to hold land, it had none to develop it. An independent company was created, although all but one of its directors were also directors of the Met.[180] MRCE developed estates at Kingsbury Garden Village near Neasden, Wembley Park, Cecil Park and Grange Estate at Pinner, and the Cedars Estate at Rickmansworth, and created places such as Harrow Garden Village.[179][180]

The term Metro-land was coined by the Met's marketing department in 1915 when the Guide to the Extension Line became the Metro-land guide, priced at 1d. This promoted the land served by the Met for the walker, visitor and later the house-hunter.[178] Published annually until 1932, the last full year of independence, the guide extolled the benefits of "The good air of the Chilterns", using language such as "Each lover of Metroland may well have his own favourite wood beech and coppice — all tremulous green loveliness in Spring and russet and gold in October".[181] The dream promoted was of a modern home in beautiful countryside with a fast railway service to central London.[182]

From about 1914 the company promoted itself as "The Met", but after 1920 the commercial manager, John Wardle, ensured that timetables and other publicity material used "Metro" instead.[1][note 33] Land development also occurred in central London when in 1929 Chiltern court, a large, luxurious block of apartments, opened at Baker Street,[182][note 34] designed by the Met's architect Charles Walter Clark, who was also responsible for the design of a number of station reconstructions in outer "Metro-land" at this time.[163]

Infrastructure improvements

To improve outer passenger services, powerful 75 mph (121 km/h) H Class steam locomotives[186] were introduced in 1920, followed in 1922–23 by new electric locomotives with a top speed of 65 mph (105 km/h).[187] The generating capacity of the power station at Neasden was increased to approximately 35 MW[188] and on 5 January 1925 electric services reached Rickmansworth, allowing the locomotive change over point to be moved.[163]

In 1924 and 1925, the British Empire Exhibition was held on the Wembley Park Estate and the adjacent Wembley Park station was rebuilt with a new island platform with a covered bridge linking to the exhibition.[189] The Met exhibited an electric multiple unit car in 1924, which returned the following year with electric locomotive No. 15, subsequently to be named "Wembley 1924".[190] A national sports arena, Wembley Stadium was built on the site of Watkin's Tower.[189] With a capacity of 125,000 spectators it was first used for the FA Cup Final on 28 April 1923 where the match was preceded by chaotic scenes as crowds in excess of capacity surged into the stadium. In the 1926 Metro-land edition, the Met boasted that that had carried 152,000 passengers to Wembley Park on that day.[182]

In 1925, a branch opened from Rickmansworth to Watford. Although there had been a railway station in Watford since 1837,[191][note 35] in 1895 the Watford Tradesmen's Association had approached the Met with a proposal for a line to Watford via Stanmore. They approached again in 1904, this time jointly with the local District Council, to discuss a new plan for a shorter branch from Rickmansworth.[192] A possible route was surveyed in 1906 and a bill deposited in 1912 seeking authority for a joint Met & GCR line from Rickmansworth to Watford town centre that would cross Cassiobury Park on an embankment. There was local opposition to the embankment and the line was cut back to a station with goods facilities just short of the park. The amended Act was passed on 7 August 1912 and the Watford Joint Committee formed before the start of World War I in 1914 delayed construction. After the war, the 1921 Trade Facilities Act offered government financial guarantees for capital projects that promoted employment, and taking advantage of this construction started in 1922. During construction the Railways Act 1921 meant that in 1923 the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) replaced the GCR. Where the branch met the extension line two junctions were built, allowing trains access to Rickmansworth and London. Services started on 3 November 1925 with one intermediate station at Croxley Green (now Croxley), with services provided by Met electric multiple units to Liverpool Street via Moor Park and Baker Street and by LNER steam trains to Marylebone.[193] The Met also ran a shuttle service between Watford and Rickmansworth.[194] During 1924–5 the flat junction north of Harrow was replaced with a 1,200 feet (370 m) long diveunder to separate Uxbridge and main-line trains.[195] Another attempt was made in 1927 to extend the Watford branch across Cassiobury Park to the town centre, the Met purchasing a property on Watford High Street with the intention of converting it to a station. The proposals for tunnelling under the park proved controversial and the scheme was dropped.[196]

There remained a bottleneck at Finchley Road where the fast and slow tracks converged into one pair for the original M&SJWR tunnels to Baker Street. In 1925, a plan was developed for two new tube tunnels, large enough for the Met rolling stock that would join the extension line at a junction north of Kilburn & Brondesbury station and run beneath Kilburn High Street, Maida Vale and Edgware Road to Baker Street.[197][198] The plan included three new stations, at Quex Road, Kilburn Park Road and Clifton Road,[199] but did not progress after Ministry of Transport revised its Requirements for Passenger Lines requiring a means of exit in an emergency at the ends of trains running in deep-level tubes – compartment stock used north of Harrow did not comply with this requirement.[200] Edgware Road station had been rebuilt with four platforms and had train destination indicators including stations such as Verney Junction and Uxbridge.[201]

In the 1920s, off-peak there was a train every 4–5 minutes from Wembley Park to Baker Street. There were generally two services per hour from both Watford and Uxbridge that ran non-stop from Wembley Park and stopping services started from Rayners Lane, Wembley Park, and Neasden, although most did not stop at Marlborough Road and St John's Wood Road. Off-peak, stations north of Moor Park were generally served by Marylebone trains. During the peak trains approached Baker Street every 2.5–3 minutes, half running through to Moorgate, Liverpool Street or Aldgate.[202] On the inner circle a train from Hammersmith ran through Baker Street every 6 minutes, and Kensington (Addison Road) services terminated at Edgware Road.[203] Maintaining a frequency of ten trains an hour on the circle was proving difficult and the solution chosen was for the District to extend its Putney to Kensington High Street service around the circle to Edgware Road, using the new platforms, and the Met to provide all the inner circle trains at a frequency of eight trains an hour.[204][note 36]

Construction started in 1929 on a branch from Wembley Park to Stanmore to serve a new housing development at Canons Park,[188] with stations at Kingsbury and Canons Park (Edgware) (renamed Canons Park in 1933).[32] The government again guaranteed finance, this time under the Development Loans Guarantees & Grants Act, the project also quadrupling the tracks from Wembley Park to Harrow. The line was electrified with automatic colour light signals controlled from a signal box at Wembley Park and opened on 9 December 1932.[188][205]

London Passenger Transport Board, 1933

Unlike the UERL, the Met profited directly from development of Metro-land housing estates near its lines;[179] the Met had always paid a dividend to its shareholders.[206] The early accounts are untrustworthy, but by the late 19th century it was paying a dividend of about 5 per cent. This dropped from 1900 onwards as electric trams and the Central London Railway attracted passengers away;[207] a low of 1⁄2 per cent was reached in 1907–8. Dividends rose to 2 per cent in 1911–13 as passengers returned after electrification; the outbreak of war in 1914 reduced the dividend to 1 per cent.[206] By 1921 recovery was sufficient for a dividend of 2 1⁄4 per cent to be paid and then, during the post-war housing boom, for the rate to steadily rise to 5 per cent in 1924–5. The 1926 General Strike reduced this to 3 per cent; by 1929 it was back to 4 per cent.[206][179]

In 1913, the Met had refused a merger proposal made by the UERL and it remained stubbornly independent under the leadership of Robert Selbie.[179] The Railways Act 1921, which became law on 19 August 1921, did not list any of London's underground railways among the companies that were to be grouped, although at the draft stage the Met had been included.[208] When proposals for integration of public transport in London were published in 1930, the Met argued that it should have the same status as the four main-line railways, and it was incompatible with the UERL because of its freight operations, although the government saw the Met in a similar way to the District as they jointly operated the inner circle. After the London Passenger Transport Bill, aimed primarily at co-ordinating the small independent bus services,[209] was published on 13 March 1931, the Met spent £11,000 opposing it.[210] The bill survived a change in government in 1931 and the Met gave no response to a proposal made by the new administration that it could remain independent if it were to lose its running powers over the circle. The directors turned to negotiating compensation for its shareholders;[211] by then passenger numbers had fallen due to competition from buses and the depression.[212] In 1932, the last full year of operation, a 1 5⁄8 per cent dividend was declared.[206] On 1 July 1933, the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB), was created as a public corporation and the Met was amalgamated with the other underground railways, tramway companies and bus operators. Met shareholders received £19.7 million in LPTB stock.[213][note 37]

Legacy

The Met became the Metropolitan line of London Transport, the Brill branch closing in 1935, followed by the line from Quainton Road to Verney Junction in 1936. The LNER took over steam workings and freight. In 1936, Metropolitan line services were extended from Whitechapel to Barking along the District line. The New Works Programme meant that in 1939 the Bakerloo line was extended from Baker Street in new twin tunnels and stations to Finchley Road before taking over the intermediate stations to Wembley Park and the Stanmore branch.[214] The branch transferred to the Jubilee line when that line opened in 1979.[32] The Great Northern and City Railway remained isolated and was managed as a section of the Northern line until being taken over by British Railways in 1976.

Steam locomotives were used north of Rickmansworth until the early 1960s when they were replaced following the electrification to Amersham and the introduction of electric multiple units, London Transport withdrawing its service north of Amersham.[215] In 1988, the route from Hammersmith to Aldgate and Barking was branded as the Hammersmith & City line, and the route from the New Cross stations to Shoreditch became the East London line, leaving the Metropolitan line as the route from Aldgate to Baker Street and northwards to stations via Harrow.

After amalgamation in 1933 the "Metro-land" brand was rapidly dropped.[182] In the mid-20th century, the spirit of Metro-land was remembered in John Betjeman's poems such as "The Metropolitan Railway" published in the A Few Late Chrysanthemums collection in 1954[216] and he later reached a wider audience with his television documentary Metro-land, first broadcast on 26 February 1973.[217] The suburbia of Metro-land is one locale of Julian Barnes' Bildungsroman novel Metroland, first published in 1980.[218] A film based on the novel, also called Metroland, was released in 1997.[219]

Accident

On 18 June 1925, electric locomotive No. 4 collided with a passenger train at Baker Street station when a signal was changed from green to red just as the locomotive was passing it. Six people were injured.[220]

Goods

Until 1880 the Met ran no goods trains, but goods trains ran over its tracks from 20 February 1866 when the GNR began a service to the LC&DR via Farringdon Street, followed by a service from the Midland Railway from July 1868. The GNR, the GWR and the Midland all opened goods depots in the Farringdon area, accessed from the City Widened Lines. Goods traffic was to play an important part of Met traffic on the extension line out of Baker Street. In 1880, the Met secured the coal traffic of the Harrow District Gas Co., worked from an exchange siding with the Midland at Finchley Road to a coal yard at Harrow. Goods and coal depots were provided at most of the stations on the extension line as they were built.[221] Goods for London were initially handled at Willesden, with delivery by road[222] or by transfer to the Midland.[223] The arrival of the GCR gave connections to the north at Quainton Road and south via Neasden, Acton and Kew.[224]

In 1909, the Met opened Vine Street goods depot near Farringdon with two sidings each seven wagons long and a regular service from West Hampstead.[note 38] Trains were electrically hauled with a maximum length of 14 wagons and restricted to 250 long tons (254 t) inwards and 225 long tons (229 t) on the return. In 1910, the depot handled 11,400 long tons (11,600 t), which rose to 25,100 long tons (25,500 t) in 1915.[226] In 1913, the depot was reported above capacity, but after World War I motor road transport became an important competitor and by the late 1920s traffic had reduced to manageable levels.[227]

Coal for the steam locomotives, the power station at Neasden and local gasworks were brought in via Quainton Road.[228][229] Milk was conveyed from Vale of Aylesbury to the London suburbs and foodstuffs from Vine Street to Uxbridge for Alfred Button & Son, wholesale grocers. Fish to Billingsgate Market via the Met and the District joint station at Monument caused some complaints, leaving the station approaches in an "indescribably filthy condition". The District suggested a separate entrance for the fish, but nothing was done. The traffic reduced significantly when the GCR introduced road transport to Marylebone, but the problem remained until 1936, being one reason the LPTB gave for abolishing the carrying of parcels on Inner Circle trains.[229]

Initially private contractors were used for road delivery, but from 1919 the Met employed its own hauliers.[222] In 1932, before it became part of London Underground, the company owned 544 goods vehicles and carried 162,764 long tons (165,376 t) of coal, 2,478,212 long tons (2,517,980 t) of materials and 1,015,501 long tons (1,031,797 t) tons of goods.[230]

Rolling stock

Steam locomotives

.jpg)

Concern about smoke and steam in the tunnels led to new designs of steam locomotive. Before the line opened, in 1861 trials were made with the experimental "hot brick" locomotive nicknamed Fowler's Ghost. This was unsuccessful and the first public trains were hauled by broad-gauge GWR Metropolitan Class condensing 2-4-0 tank locomotives designed by Daniel Gooch. They were followed by standard-gauge GNR locomotives[231] until the Met received its own 4-4-0 tank locomotives, built by Beyer Peacock of Manchester. Their design is frequently attributed to the Met's Engineer John Fowler, but the locomotive was a development of one Beyer had built for the Spanish Tudela to Bilbao Railway, Fowler specifying only the driving wheel diameter, axle weight and the ability to navigate sharp curves.[37] Eighteen were ordered in 1864, initially carrying names,[232] and by 1870 40 had been built. To reduce smoke underground, at first coke was burnt, changed in 1869 to smokeless Welsh coal.[42]

From 1879, more locomotives were needed, and the design was updated and 24 were delivered between 1879 and 1885.[233] Originally they were painted bright olive green lined in black and yellow, chimneys copper capped with the locomotive number in brass figures at the front and domes of polished brass. In 1885, the colour changed to a dark red known as Midcared, and this was to remain the standard colour, taken up as the colour for the Metropolitan line by London Transport in 1933.[234] When in 1925 the Met classified its locomotives by letters of the alphabet, these were assigned A Class and B Class.[210] When the M&SJWR was being built, it was considered that they would struggle on the gradients and five Worcester Engine 0-6-0 tank locomotives were delivered in 1868. It was soon found that A and B Classes could manage trains without difficulty and the 0-6-0Ts were sold to the Taff Vale Railway in 1873 and 1875.[235]

From 1891, more locomotives were needed for work on the extension line from Baker Street into the country. Four C Class (0-4-4) locomotives, a development of South Eastern Railway's 'Q' Class, were received in 1891.[236][235] In 1894, two D Class locomotives were bought to run between Aylesbury and Verney Junction. These were not fitted with the condensing equipment needed to work south of Finchley Road.[237] Four more were delivered in 1895 with condensing equipment, although these were prohibited working south of Finchley Road.[238] In 1896, two E Class (0-4-4) locomotives were built at Neasden works, followed by one in 1898 to replace the original Class A No. 1, damaged in an accident. Four more were built by Hawthorn Leslie & Co in 1900 and 1901.[239] To cope with the growing freight traffic on the extension line, the Met received four F Class (0-6-2) locomotives in 1901, similar to the E Class except for the wheel arrangement and without steam heat.[240] In 1897 and 1899, the Met received two 0-6-0 saddle tank locomotives to a standard Peckett design. Unclassified by the Met, these were generally used for shunting at Neasden and Harrow.[241]

Many locomotives were made redundant by the electrification of the inner London lines in 1905–06. By 1907, 40 of the class A and B locomotives had been sold or scrapped and by 1914 only 13 locomotives of these classes had been retained[242] for shunting, departmental work and working trains over the Brill Tramway.[243] The need for more powerful locomotives for both passenger and freight services meant that, in 1915, four G Class (0-6-4) locomotives arrived from Yorkshire Engine Co.[244] Eight 75 mph (121 km/h) capable H Class (4-4-4) locomotives were built in 1920 and 1921 and used mainly on express passenger services.[245] To run longer, faster and less frequent freight services in 1925 six K Class (2-6-4) locomotives arrived, rebuilt from 2-6-0 locomotives manufactured at Woolwich Arsenal after World War I. These were not permitted south of Finchley Road.[246]

Two locomotives survive: A Class No. 23 (LT L45) at the London Transport Museum,[247] and E Class No. 1 (LT L44) at the Buckinghamshire Railway Centre.[248] No.1 ran in steam as part of the Met's 150th anniversary celebrations during 2013.[249]

Carriages

The Met opened with no stock of its own, with the GWR and then the GNR providing services. The GWR used eight-wheeled compartment carriages constructed from teak. By 1864, the Met had taken delivery of its own stock, made by the Ashbury Railway Carriage & Iron Co., based on the GWR design but standard gauge.[231][note 39] Lighting was provided by gas — two jets in first class compartments and one in second and third class compartments,[252] and from 1877 a pressurised oil gas system was used.[253] Initially the carriages were braked with wooden blocks operated by hand from the guards' compartments at the front and back of the train, giving off a distinctive smell.[254][255] This was replaced in 1869 by a chain that operated brakes on all carriages. The operation of the chain brake could be abrupt, leading to some passenger injuries, and it was replaced by a non-automatic vacuum brake by 1876.[256][253] In the 1890s, a mechanical 'next station' indicator was tested in some carriages on the circle, triggered by a wooden flap between the tracks. It was considered unreliable and not approved for full installation.[257]

In 1870, some close-coupled rigid-wheelbase four-wheeled carriages were built by Oldbury.[258] After some derailments in 1887, a new design of 27 feet 6 inches (8.38 m) long rigid-wheelbase four-wheelers known as Jubilee Stock was built by the Cravens Railway Carriage and Wagon Co. for the extension line. With the pressurised gas lighting system and non-automatic vacuum brakes from new, steam heating was added later. More trains followed in 1892, although all had been withdrawn by 1912.[259] By May 1893, following an order by the Board of Trade, automatic vacuum brakes had been fitted to all carriages and locomotives.[260] A Jubilee Stock first class carriage was restored to carry passengers during the Met's 150th anniversary celebrations.[249][261]

Bogie stock was built by Ashbury in 1898 and by Cravens and at Neasden Works in 1900. This gave a better ride quality, steam heating, automatic vacuum brakes, electric lighting and upholstered seating in all classes.[236][262][263] The Bluebell Railway has four 1898–1900 Ashbury and Cravens carriages and a fifth, built at Neasden, is at the London Transport Museum.[264]

Competition with the GCR on outer suburban services on the extension line saw the introduction of more comfortable Dreadnought Stock carriages from 1910.[152] Ninety-two of these wooden compartment carriages were built, fitted with pressurised gas lighting and steam heating.[265] Electric lighting had replaced the gas by 1917 and electric heaters were added in 1922 to provide warmth when hauled by an electric locomotive.[263] Later formed into rakes of five, six or seven coaches,[266] conductor rail pick-ups on the leading and trailing guard coaches were joined by a bus line and connected to the electric locomotive to help prevent gapping.[265] Two rakes were formed with a Pullman coach that provided a buffet service for a supplementary fare.[267][note 40] The Vintage Carriages Trust has three preserved Dreadnought carriages.[270]

From 1906, some of the Ashbury bogie stock was converted into electric multiple units.[271] Some Dreadnought carriages were used with electric motor cars, although two-thirds remained in use as locomotive hauled stock on the extension line.[272]

Electric locomotives

.jpg)

After electrification, the outer suburban routes were worked with carriage stock hauled from Baker Street by an electric locomotive that was exchanged for a steam locomotive en route. The Met ordered 20 electric locomotives from Metropolitan Amalgamated with two types of electrical equipment. The first ten, with Westinghouse equipment, entered service in 1906. These 'camel-back' bogie locomotives had a central cab,[152] weighed 50 tons,[273] and had four 215 hp (160 kW) traction motors[274] The second type were built to a box car design with British Thomson-Houston equipment,[152] replaced with the Westinghouse type in 1919.[274]

In the early 1920s, the Met placed an order with Metropolitan-Vickers of Barrow-in-Furness for rebuilding the 20 electric locomotives. When work started on the first locomotive, it was found to be impractical and uneconomical and the order was changed to building new locomotives using some equipment recovered from the originals. The new locomotives were built in 1922–23 and named after famous London residents. They had four 300 hp (220 kW) motors, totalling 1,200 hp (890 kW) (one-hour rating), giving a top speed of 65 mph (105 km/h).[187]

No. 5 "John Hampden" is preserved as a static display at the London Transport Museum[275] and No. 12 "Sarah Siddons" has been used for heritage events, and ran during the Met's 150th anniversary celebrations.[276]

Electric multiple units

The first order for electric multiple units was placed with Metropolitan Amalgamated in 1902 for 50 trailers and 20 motor cars with Westinghouse equipment, which ran as 6-car trains. First and third class accommodation was provided in open saloons, second class being withdrawn from the Met.[277] Access was at the ends via open lattice gates[278] and the units were modified so that they could run off-peak as 3-car units.[279] For the joint Hammersmith & City line service, the Met and the GWR purchased 20 × 6-cars trains with Thomson-Houston equipment.[280] In 1904, a further order was placed by the Met for 36 motor cars and 62 trailers with an option for another 20 motor cars and 40 trailers. Problems with the Westinghouse equipment led to Thomson-Houston equipment being specified when the option was taken up and more powerful motors being fitted.[278] Before 1918, the motor cars with the more powerful motors were used on the circle with three trailers.[281] The open lattice gates were seen as a problem when working above ground and all of the cars had gates replaced with vestibules by 1907.[279] Having access only through the two end doors became a problem on the busy circle and centre sliding doors were fitted from 1911.[282]

From 1906, some of the Ashbury bogie stock was converted into multiple units by fitting cabs, control equipment and motors.[271] In 1910, two motor cars were modified with driving cabs at both ends. They started work on the Uxbridge-South Harrow shuttle service, being transferred to the Addison Road shuttle in 1918. From 1925 to 1934 these vehicles were used between Watford and Rickmansworth.[283]

In 1913, an order was placed for 23 motor cars and 20 trailers, saloon cars with sliding doors at the end and the middle. These started work on the circle, including the new service to New Cross via the ELR. [284] In 1921, 20 motor cars, 33 trailers and six first-class driving trailers were received with three pairs of double sliding doors on each side. These were introduced on the circle.[285]

Between 1927 and 1933 multiple unit compartment stock was built by the Metropolitan Carriage and Wagon and Birmingham Railway Carriage and Wagon Co. for services from Baker Street and the City to Watford and Rickmansworth. The first order was only for motor cars; half had Westinghouse brakes, Metro-Vickers control systems and four MV153 motors; they replaced the motor cars working with bogie stock trailers. The rest of the motor cars had the same motor equipment but used vacuum brakes, and worked with converted 1920/23 Dreadnought carriages to form 'MV' units. In 1929, 'MW' stock was ordered, 30 motor coaches and 25 trailers similar to the 'MV' units, but with Westinghouse brakes. A further batch of 'MW' stock was ordered in 1931, this time from the Birmingham Railway Carriage & Wagon Co. This was to make seven 8-coach trains, and included additional trailers to increase the length of the previous 'MW' batch trains to eight coaches. These had GEC WT545 motors, and although designed to work in multiple with the MV153, this did not work well in practice. After the Met became part of London Underground, the MV stock was fitted with Westinghouse brakes and the cars with GEC motors were re-geared to allow them to work in multiple with the MV153-motored cars. In 1938, nine 8-coach and ten 6-coach MW units were re-designated T Stock.[286] A trailer coach built in 1904/5 is stored at London Transport Museum's Acton Depot, although it has been badly damaged by fire,[287] and the Spa Valley Railway is home to two T stock coaches.[288]

Notes

- ↑ The company promoted itself as "The Met" from about 1914.[1] The Railway is referred to as "the Met" or "the Metropolitan" in historical accounts such as Jackson 1986, Simpson 2003, Horne 2003, Green 1987, and Bruce 1983.

- ↑ In 1801, approximately one million people lived in the area that is now Greater London. By 1851 this had doubled.[3]

- ↑ The area of the ban was bounded by London Bridge, Borough High Street, Blackman Street, Borough Street, Lambeth Road, Vauxhall Road, Vauxhall Bridge, Vauxhall Bridge Road, Grosvenor Place, Park Lane, Edgware Road, New Road, City Road, Finsbury Square, and Bishopsgate.[7]

- ↑ The route was to run from the south end of Westbourne Terrace, under Grand Junction Road (now Sussex Gardens), Southampton Road (now Old Marylebone Road) and New Road (now Marylebone Road and Euston Road). A branch was planned to connect to the GWR terminus.[10]

- ↑ Time limits were included in such legislation to encourage the railway company to complete the construction of its line as quickly as possible. They also prevented unused permissions acting as an indefinite block to other proposals.

- ↑ Instead of connecting to the GWR's terminus, the Met built its own station at Bishop's Road parallel to Paddington station and to the north. The Met connected to the GWR's tracks beyond Bishop's Road station.[16]

- ↑ The shares were later sold by the corporation for a profit.[17]

- ↑ Contractors for the works were Smith & Knight to the west of Euston Square and John Jay on the eastern section.[16]

- ↑ According to the Metropolitan Railway, the cost of constructing the line on an elevated viaduct would have been four times the cost of constructing it in tunnel.[29]

- ↑ Built by Beyer Peacock of Manchester the design of the locomotives is frequently attributed to the Metropolitan Engineer John Fowler, but the locomotive was a development of one Beyer Peacock had built for the Spanish Tudela to Bilbao Railway, Fowler specifying only the driving wheel diameter, axle weight, and the ability to navigate sharp curves.[37]

- ↑ This report noted that between Edgware Road and King's Cross there were 528 passenger and 14 freight trains every weekday and during the peak hour there were 19 trains each way between Baker Street and King's Cross, 15 long cwt (760 kg) of coal was burnt and 1,650 imp gal (7,500 L) water was used, half of which was condensed, the rest evaporating.[44]

- ↑ In the Metropolitan Railway Act 1861 and the Metropolitan Railway (Finsbury Circus Extension) Act 1861 and Metropolitan Railway Act was given royal assent on 25 July 1864 approving the additional tracks to King's Cross.

- ↑ One of these tunnels, completed in 1862, was used to bring the GNR-loaned rolling stock on to the Metropolitan Railway when the GWR withdrew its trains in August 1863.[49]

- ↑ For a Hammersmith, Paddington and City Junction Railway.[56]

- ↑ The L&SWR tracks to Richmond now form part of the London Underground's District line. Stations between Hammersmith and Richmond served by the Met were Ravenscourt Park, Turnham Green, Gunnersbury, and Kew Gardens.[32]

- ↑ In November 1863, The Times reported that about 30 railway schemes for London had been submitted for consideration in the next parliamentary session. Many of which seemed "to have been prepared on the spur of the moment, without much consideration either as to the cost of construction or as to the practicability of working them when made."[65]

- ↑ These Acts were the Metropolitan Railway (Notting Hill and Brompton Extension) Act and the Metropolitan Railway (Tower Hill Extension) Act, and the Metropolitan District Railway Act created the Metropolitan District Railway.[66]

- ↑ Sources differ about the running of the first 'inner circle' services. Jackson 1986, p. 56 says the operation was shared equally, whereas Lee 1956, pp. 28–29 states the Met ran all the services.

- ↑ The station was completed on 19 July 1871, the Metropolitan and the District running a joint connecting bus service from the station to the 1871 International Exhibition.[81]