Metronidazole

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /mɛtrəˈnaɪdəzoʊl/ |

| Trade names | Flagyl, Metro, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | by mouth, topical, rectal, IV, vaginal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80% (oral), 60–80% (rectal), 20–25% (vaginal)[1][2] |

| Protein binding | 20%[1][2] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic[1][2] |

| Biological half-life | 8 hours[1][2] |

| Excretion | Urine (77%), faeces (14%)[1][2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| PDB ligand | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.489 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

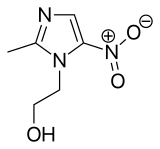

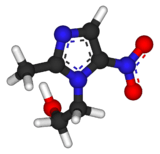

| Formula | C6H9N3O3 |

| Molar mass | 171.15 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 159 to 163 °C (318 to 325 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Metronidazole (MNZ), marketed under the brand name Flagyl among others, is an antibiotic and antiprotozoal medication.[3] It is used either alone or with other antibiotics to treat pelvic inflammatory disease, endocarditis, and bacterial vaginosis. It is effective for dracunculiasis, giardiasis, trichomoniasis, and amebiasis.[3] It is the drug of choice for a first episode of mild-to-moderate Clostridium difficile colitis.[4] Metronidazole is available by mouth, as a cream, and intravenously.[3]

Common side effects include nausea, a metallic taste, loss of appetite, and headaches. Occasionally seizures or allergies to the medication may occur.[3] Some state that metronidazole should not be used in early pregnancy while others state doses for trichomoniasis are okay.[5] It should not be used when breastfeeding.[5]

Metronidazole began to be commercially used in 1960 in France.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[7] It is available in most areas of the world.[8] The pills are relatively inexpensive, costing between 0.01 and 0.10 USD each.[9][10] In the United States it is about 26 USD for ten days of treatment.[3]

Medical uses

Metronidazole is primarily used to treat: bacterial vaginosis, pelvic inflammatory disease (along with other antibacterials like ceftriaxone), pseudomembranous colitis, aspiration pneumonia, rosacea (topical), fungating wounds (topical), intra-abdominal infections, lung abscess, periodontitis, amoebiasis, oral infections, giardiasis, trichomoniasis, and infections caused by susceptible anaerobic organisms such as Bacteroides, Fusobacterium, Clostridium, Peptostreptococcus, and Prevotella species.[11] It is also often used to eradicate Helicobacter pylori along with other drugs and to prevent infection in people recovering from surgery.[11]

Bacterial vaginosis

Drugs of choice for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis include metronidazole and clindamycin. The treatment of choice for bacterial vaginosis in nonpregnant women include metronidazole oral twice daily for seven days, or metronidazole gel intravaginally once daily for five days, or clindamycin intravaginally at bedtime for seven days. For pregnant women, the treatment of choice is metronidazole oral three times a day for seven days. Data does not report routine treatment of male sexual partners.[12]

Trichomoniasis

The 5-nitroimidazole drugs (metronidazole and tinidazole) are the mainstay of treatment for infection with Trichomonas vaginalis. Treatment for both the infected patient and the patient's sexual partner is recommended, even if asymptomatic. Therapy other than 5-nitroimidazole drugs is also an option, but cure rates are much lower.[13]

Giardiasis

Oral metronidazole is a treatment option for giardiasis, however, the increasing incidence of nitroimidazole resistance is leading to the increased use of other compound classes.

Dracunculus

In the case of Dracunculus (guinea worm), metronidazole just eases worm extraction rather than killing the worm.[3]

C. difficile colitis

Initial antibiotic therapy for less-severe Clostridium difficile colitis (pseudomembranous colitis) consists of oral metronidazole or oral vancomycin. Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated equivalent efficacy of oral metronidazole and oral vancomycin in treating this colitis.[14][15][16] However, oral vancomycin is shown to be more effective in treating patients with severe C. difficile colitis.[14]

E. histolytica

Invasive colitis and extraintestinal disease including liver abscesses, pleuropulmonary infections, and brain abscesses can result from infection with Entamoeba histolytica. Metronidazole is widely used in patients with these infections.

Preterm births

Metronidazole has also been used in women to prevent preterm birth associated with bacterial vaginosis, amongst other risk factors including the presence of cervicovaginal fetal fibronectin (fFN). Metronidazole was ineffective in preventing preterm delivery in high-risk pregnant women (selected by history and a positive fFN test) and, conversely, the incidence of preterm delivery was found to be higher in women treated with metronidazole.[17]

Adverse effects

Common adverse drug reactions (≥1% of those treated with the drug) associated with systemic metronidazole therapy include: nausea, diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, vomiting, headache, dizziness, and metallic taste in the mouth. Intravenous administration is commonly associated with thrombophlebitis. Infrequent adverse effects include: hypersensitivity reactions (rash, itch, flushing, fever), headache, dizziness, vomiting, glossitis, stomatitis, dark urine, and paraesthesia.[11] High doses and long-term systemic treatment with metronidazole are associated with the development of leucopenia, neutropenia, increased risk of peripheral neuropathy, and central nervous system toxicity.[11] Common adverse drug reaction associated with topical metronidazole therapy include local redness, dryness and skin irritation; and eye watering (if applied near eyes).[11] Metronidazole has been associated with cancer in animal studies.[18]

Metronidazole may cause mood swings. Some evidence from studies in rats indicates the possibility it may contribute to serotonin syndrome, although no case reports documenting this have been published to date.[19][20]

Mutagenesis and carcinogenesis

Metronidazole is listed by the US National Toxicology Program (NTP) as reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen.[21] Although some of the testing methods have been questioned, oral exposure has been shown to cause cancer in experimental animals and has also demonstrated some mutagenic effects in bacterial cultures.[21][22] The relationship between exposure to metronidazole and human cancer is unclear.[21][23] One study [24] found an excess in lung cancer among women (even after adjusting for smoking), while other studies [25] found either no increased risk, or a statistically insignificant risk.[21] [26] Metronidazole is listed as a possible carcinogen according to the WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer.[27] A study in those with Crohn's disease also found chromosomal abnormalities in circulating lymphocytes in people treated with metronidazole.[22]

Stevens–Johnson syndrome

Metronidazole alone rarely causes Stevens–Johnson syndrome, but is reported to occur at high rates when combined with mebendazole.[28]

Drug interactions

Alcohol

Consuming alcohol while taking metronidazole has long been thought to have a disulfiram-like reaction with effects that can include nausea, vomiting, flushing of the skin, tachycardia, and shortness of breath.[29] Consumption of alcohol is typically advised against by patients during systemic metronidazole therapy and for at least 48 hours after completion of treatment.[11] However, some studies call into question the mechanism of the interaction of alcohol and metronidazole,[30][31][32] and a possible central toxic serotonin reaction for the alcohol intolerance is suggested.[19] Metronidazole is also generally thought to inhibit the liver metabolism of propylene glycol (found in some foods, medicines, and in many electronic cigarette e-liquids), thus propylene glycol may potentially have similar interaction effects with metronidazole.

Other drug interactions

It also inhibits CYP2C9, so may interact with medications metabolised by these enzymes (e.g. lomitapide, warfarin).[1]

Mechanism of action

Metronidazole is of the nitroimidazole class. It inhibits nucleic acid synthesis by disrupting the DNA of microbial cells.[1] This function only occurs when metronidazole is partially reduced, and because this reduction usually happens only in anaerobic cells, it has relatively little effect upon human cells or aerobic bacteria.[33]

Synthesis

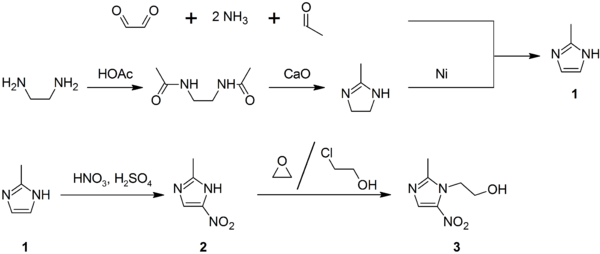

2-Methylimidazole (1) may be prepared via the Debus-Radziszewski imidazole synthesis, or from ethylenediamine and acetic acid, followed by treatment with lime, then Raney nickel. 2-Methylimidazole is nitrated to give 2-methyl-4(5)-nitroimidazole (2), which is in turn alkylated with ethylene oxide or 2-chloroethanol to give metronidazole (3):[34][35][36]

Veterinary use

Metronidazole is widely used to treat infections of Giardia in dogs, cats, and other companion animals, although it does not reliably clear infection with this organism and is being supplanted by fenbendazole for this purpose in dogs and cats.[37] It is also used for the management of chronic inflammatory bowel disease in cats and dogs.[38] Another common usage is the treatment of systemic and/or gastrointestinal clostridial infections in horses. Metronidazole is used in the aquarium hobby to treat ornamental fish and as a broad-spectrum treatment for bacterial and protozoan infections in reptiles and amphibians. In general, the veterinary community may use metronidazole for any potentially susceptible anaerobic infection. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration suggests it only be used when necessary because it has been shown to be carcinogenic in mice and rats, as well as the microbes for which it is prescribed, and resistance can develop.[39][40]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Flagyl, Flagyl ER (metronidazole) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brayfield, A, ed. (14 January 2014). "Metronidazole". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Metronidazole". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ↑ Cohen, Stuart H.; Gerding, Dale N.; Johnson, Stuart; Kelly, Ciaran P.; Loo, Vivian G.; McDonald, L. Clifford; Pepin, Jacques; Wilcox, Mark H. (May 2010). "Clinical Practice Guidelines for Infection in Adults: 2010 Update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 31 (5): 431–455. PMID 20307191. doi:10.1086/651706.

- 1 2 "Metronidazole Use During Pregnancy | Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ↑ Corey, E.J. (2013). Drug discovery practices, processes, and perspectives. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. p. 27. ISBN 9781118354469.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Schmid G (28 July 2003). "Trichomoniasis treatment in women". Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ↑ "Sources and Prices of Selected Medicines and Diagnostics for People Living with HIV/AIDS". World Health Organization. 2005. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ↑ Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases (8 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. 2014. p. 2753. ISBN 9780323263733.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ↑ Joesoef, MR; Schmid, GP; Hillier, SL (Jan 1999). "Bacterial vaginosis: review of treatment options and potential clinical indications for therapy.". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 28 Suppl 1: S57–65. PMID 10028110. doi:10.1086/514725.

- ↑ Dubouchet, L; Spence, M. R.; Rein, M. F.; Danzig, M. R.; McCormack, W. M. (1997). "Multicenter comparison of clotrimazole vaginal tablets, oral metronidazole, and vaginal suppositories containing sulfanilamide, aminacrine hydrochloride, and allantoin in the treatment of symptomatic trichomoniasis". Sexually transmitted diseases. 24 (3): 156–60. PMID 9132982. doi:10.1097/00007435-199703000-00006.

- 1 2 Zar, F. A.; Bakkanagari, S. R.; Moorthi, K. M.; Davis, M. B. (2007). "A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 45 (3): 302–7. PMID 17599306. doi:10.1086/519265.

- ↑ Wenisch, C; Parschalk, B; Hasenhündl, M; Hirschl, A. M.; Graninger, W (1996). "Comparison of vancomycin, teicoplanin, metronidazole, and fusidic acid for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 22 (5): 813–8. PMID 8722937. doi:10.1093/clinids/22.5.813.

- ↑ Teasley, D. G.; Gerding, D. N.; Olson, M. M.; Peterson, L. R.; Gebhard, R. L.; Schwartz, M. J.; Lee Jr, J. T. (1983). "Prospective randomised trial of metronidazole versus vancomycin for Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhoea and colitis". Lancet. 2 (8358): 1043–6. PMID 6138597. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91036-x.

- ↑ Shennan, A.; Crawshaw, S.; Briley, A.; Hawken, J.; Seed, P.; Jones, G.; Poston, L. (2005). "General obstetrics: A randomised controlled trial of metronidazole for the prevention of preterm birth in women positive for cervicovaginal fetal fibronectin: The PREMET Study". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 113 (1): 65–74. PMID 16398774. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00788.x.

- ↑ FDA Drug Safety Datasheet for Flagyl, http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/012623s061lbl.pdf

- 1 2 Karamanakos, P.; Pappas, P.; Boumba, V.; Thomas, C.; Malamas, M.; Vougiouklakis, T.; Marselos, M. (2007). "Pharmaceutical Agents Known to Produce Disulfiram-Like Reaction: Effects on Hepatic Ethanol Metabolism and Brain Monoamines". International Journal of Toxicology. 26 (5): 423–432. PMID 17963129. doi:10.1080/10915810701583010.

- ↑ Karamanakos, P. N. (2008). "The possibility of serotonin syndrome brought about by the use of metronidazole". Minerva Anestesiologica. 74 (11): 679. PMID 18971895.

- 1 2 3 4 "Metronidazole CAS No. 443-48-1" (pdf). Report on Carcinogens, Twelfth Edition (2011). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Toxicology Program. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- 1 2 "Metrogyl Metronidazole Product Information" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Alphapharm Pty Limited. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ↑ Bendesky, A; Menéndez, D; Ostrosky-Wegman, P (June 2002). "Is metronidazole carcinogenic?". Mutation Research. 511 (2): 133–44. PMID 12052431. doi:10.1016/S1383-5742(02)00007-8.

- ↑ (Beard et al. 1988)

- ↑ (IARC 1987; Thapa et al. 1998)

- ↑ "Flagyl 375 U.S. Prescribing Information" (pdf). Pfizer.

- ↑ International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) (May 2010). "Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–100" (PHP). World Health Organization. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ↑ Chen, K. T.; Twu, S. J.; Chang, H. J.; Lin, R. S. (2003). "Outbreak of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome / Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Associated with Mebendazole and Metronidazole Use Among Filipino Laborers in Taiwan". American Journal of Public Health. 93 (3): 489–492. PMC 1447769

. PMID 12604501. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.3.489.

. PMID 12604501. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.3.489. - ↑ Cina, S. J.; Russell, R. A.; Conradi, S. E. (1996). "Sudden death due to metronidazole/ethanol interaction". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 17 (4): 343–346. PMID 8947362. doi:10.1097/00000433-199612000-00013.

- ↑ Gupta, N. K.; Woodley, C. L.; Fried, R. (1970). "Effect of metronidazole on liver alcohol dehydrogenase". Biochemical Pharmacology. 19 (10): 2805–2808. PMID 4320226. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(70)90108-5.

- ↑ Williams, C. S.; Woodcock, K. R. (2000). "Do ethanol and metronidazole interact to produce a disulfiram-like reaction?". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 34 (2): 255–7. PMID 10676835. doi:10.1345/aph.19118.

the authors of all the reports presumed the metronidazole-ethanol reaction to be an established pharmacologic fact. None provided evidence that could justify their conclusions

- ↑ Visapää, J. P.; Tillonen, J. S.; Kaihovaara, P. S.; Salaspuro, M. P. (2002). "Lack of disulfiram-like reaction with metronidazole and ethanol". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 36 (6): 971–974. PMID 12022894. doi:10.1345/1542-6270(2002)036<0971:lodlrw>2.0.co;2.

- ↑ Eisenstein, B. I.; Schaechter, M. (2007). "DNA and Chromosome Mechanics". In Schaechter, M.; Engleberg, N. C.; DiRita, V. J.; et al. Schaechter's Mechanisms of Microbial Disease. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7817-5342-5.

- ↑ Ebel, K.; Koehler, H.; Gamer, A. O.; Jäckh, R. (2005), "Imidazole and Derivatives", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Weinheim: Wiley-VCH, doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_661

- ↑ Actor, P.; Chow, A. W.; Dutko, F. J.; McKinlay, M. A. (2005), "Chemotherapeutics", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Weinheim: Wiley-VCH, doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_173

- ↑ Kraft, M. Ya.; Kochergin, P. M.; Tsyganova, A. M.; Shlikhunova, V. S. (1989). "Synthesis of metronidazole from ethylenediamine". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 23 (10): 861–863. doi:10.1007/BF00764821.

- ↑ Barr, S. C.; Bowman, D. D.; Heller, R. L. (1994). "Efficacy of fenbendazole against giardiasis in dogs". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 55 (7): 988–990. PMID 7978640.

- ↑ Hoskins, J. D. (Oct 1, 2001). "Advances in managing inflammatory bowel disease". DVM Newsmagazine. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ Plumb, D. C. (2008). Veterinary Drug Handbook (6th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-8138-2056-1.

- ↑ "Metronidazole". Drugs.com.

External links

- "Metronidazole for veterinary use". Wedgewood pharmacy.

- "Metronidazole". Merck manuals.

- "Metronidazole". patient.info.

- "Metronidazole". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.