Metro-North Railroad

|

| |

|

Metro-North Railroad provides services in the lower Hudson Valley and coastal Connecticut. | |

| Reporting mark | MNCW |

|---|---|

| Locale | Southeastern New York; Southwestern Connecticut |

| Dates of operation | 1983–present |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Headquarters | 420 Lexington Ave New York, NY 10017 |

| Website |

mta |

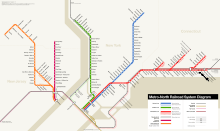

The Metro-North Commuter Railroad (reporting mark MNCW), trading as MTA Metro-North Railroad or simply Metro-North, is a suburban commuter rail service run by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), a public authority of the state of New York. With an average weekday ridership of 298,900 in 2014, it is the second-busiest commuter railroad in North America in terms of annual ridership, behind its sister railroad, the Long Island Rail Road.[1][2] Metro-North runs service between New York City and its northern suburbs in New York and Connecticut, including Port Jervis, Spring Valley, Poughkeepsie, White Plains, and Wassaic in New York and New Canaan, Danbury, Waterbury, and New Haven in Connecticut. Metro-North also provides local rail service within New York City at a reduced fare. There are 124 stations[3] on Metro-North Railroad's five active lines (plus the Meadowlands Rail Line), which operate on more than 775 miles (1,247 km) of track,[4] with the passenger railroad system totaling 385 miles (620 km) of route.[5]

The MTA has jurisdiction, through Metro-North, over railroad lines on the western and eastern portions of the Hudson River in New York. Service on the western side of the Hudson is operated by New Jersey Transit under contract with the MTA.

Lines

East of the Hudson River

Three lines provide passenger service on the east side of the Hudson River to Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan: the Hudson, Harlem, and New Haven Lines. The Beacon Line is a freight line owned by Metro-North but is not in service.

The Hudson and Harlem Lines terminate in Poughkeepsie and Wassaic, New York, respectively.

The New Haven Line is operated through a partnership between Metro-North and the State of Connecticut. The Connecticut Department of Transportation (ConnDOT) owns the tracks and stations within Connecticut, and finances and performs capital improvements. MTA owns the tracks and stations and handles capital improvements within New York State. MTA performs routine maintenance and provides police services for the entire line, its branches and stations. New cars and locomotives are typically purchased in a joint agreement between MTA and ConnDOT, with the agencies paying for 33.3% and 66.7% of costs respectively. ConnDOT pays more because most of the line is in Connecticut.

The New Haven Line has three branches in Connecticut: the New Canaan Branch, Danbury Branch and Waterbury Branch. At New Haven, the Shore Line East connecting service, run by Connecticut, continues east to New London.

Amtrak operates intercity train service along the New Haven and Hudson Lines. The New Haven Line is part of Amtrak's Northeast Corridor, and high-speed Acela Express trains run from New Rochelle to New Haven Union Station. At New Haven, the New Haven Line connects to the Amtrak New Haven–Springfield Line.

Freight trains run on Metro-North. The Hudson Line connects with the Oak Point Link and is the main route for freight to and from the Bronx and Long Island. Freight railroads CSX, CP Rail, P&W, and Housatonic Railroad have trackage rights on sections of the system. See Rail freight transportation in New York City and Long Island

West of the Hudson

Metro-North provides service west of the Hudson River on trains from Hoboken Terminal, New Jersey, jointly run with New Jersey Transit under contract. There are two branches: the Port Jervis Line and the Pascack Valley Line.[6] The Port Jervis Line is accessed from two New Jersey Transit lines, the Main Line and the Bergen County Line.

The Port Jervis Line terminates in Port Jervis, New York, and the Pascack Valley line in Spring Valley, New York, in Orange and Rockland Counties, respectively. Trackage on the Port Jervis Line north of the Suffern Yard is leased from the Norfolk Southern Railway by the MTA, but New Jersey Transit owns all of the Pascack Valley Line, including the portion in Rockland County, New York.

Most stops for the Port Jervis and Pascack Valley Lines are in New Jersey, so New Jersey Transit provides most of the rolling stock and all the staff; Metro-North supplies some equipment. Metro-North equipment has been used on other New Jersey Transit lines on the Hoboken division.

All stations west of the Hudson River in New York are owned and operated by Metro-North, except Suffern, which is owned and operated by New Jersey Transit.

History

New York Central, New Haven, and Erie Lackawanna operations

Most of the trackage east of the Hudson River and in New York State was under the control of the New York Central Railroad (NYC). The NYC initially operated three commuter lines, two of which ran into Grand Central Terminal. Metro-North's Harlem Line was initially a combination of trackage from the New York and Harlem Railroad and the Boston and Albany Railroad, running from Manhattan to Chatham, New York in Columbia County. At Chatham, passengers could transfer to long distance trains on the Boston and Albany to Albany, Boston, Vermont, and Canada.[7] On April 1, 1873, the New York and Harlem Railroad was leased by Commodore Vanderbilt, who added the railroad to his complex empire of railroads, which were run by the NYC.[8] The Boston and Albany came under the ownership of NYC in 1914.

NYC's four-track Water Level Route paralleled the Hudson River, Erie Canal, and Great Lakes on a route from New York to Chicago via Albany. It was fast and popular due to the lack of any significant grades. The section between Grand Central and Peekskill, New York, the northern most station in Westchester County, became known as the NYC's Hudson Division, with frequent commuter service in and out of Manhattan. Stations to the north of Peekskill, such as Poughkeepsie, were considered to be long distance services. The other major commuter line was the Putnam Division running from 155th Street in upper Manhattan (later from Sedgwick Avenue in The Bronx) to Brewster, New York. Passengers would transfer to the IRT Ninth Avenue Line for midtown and downtown Manhattan.

From the mid-19th century until 1969, the New Haven Line, including the New Canaan, Danbury, and Waterbury branches, was owned by the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad (NYNH&H). These branches were started in the 1830s with horse-drawn cars, later replaced by steam engines, on a route that connected Lower Manhattan to Harlem. Additional lines started in the mid-19th century included the New York and New Haven Railroad and the Hartford and New Haven Railroad, which provided routes to Hartford, Springfield, Massachusetts, and eventually Boston. The two roads merged in 1872 to become the NYNH&H, growing into the largest passenger and commuter carrier in New England. In the early 20th century, the NYNH&H came under the control of J.P. Morgan. Morgan's bankroll allowed the NYNH&H to modernize by upgrading steam power with both electric (along the New Haven Line) and diesel power (branches and lines to eastern and northern New England). The NYNH&H saw much profitability throughout the 1910s and 1920s until the Great Depression of the 1930s forced it into bankruptcy.[9]

Commuter services west of the Hudson River, today's Port Jervis and Pascack Valley lines, were initially part of the Erie Railroad. The Port Jervis Line, built in the 1850s and 1860s, was originally part of the Erie's mainline from Jersey City to Buffalo, New York. The Pascack Valley Line was built by the New Jersey and New York Railroad, which became a subsidiary of the Erie. Trains that service Port Jervis formerly continued to Binghamton and Buffalo, New York (today used only by freight trains), while Pascack Valley service continued to Haverstraw, New York. In 1956, the Erie Railroad began coordinated service with rival Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad, and in 1960 they formed the Erie Lackawanna. Trains were rerouted to the Lackawanna's Hoboken Terminal in 1956-1958.

Penn Central

Passenger rail in the United States began to falter after World War II. By the 1950s, the railroad industry began to experience a significant downturn due to over-regulation, market saturation, and, more importantly, competition from the car, bus and airplane. Commuter lines took a significant hit from this downfall.

Commuter services historically had always been money losers, and were usually subsidized by long-distance passenger and freight services. As these profits disappeared, commuter services usually were the first to be affected. Many railroads began to gradually discontinue their commuter lines after the war. By 1958, the NYC had already suspended service on its Putnam Division, while the newly formed Erie Lackawanna, in an effort to make a successful merger, began to prune some of its commuter services. Most New Yorkers still chose the train as their primary means of commuting, making many of the other lines heavily patronized. Thus the NYC, the NYNH&H, and the Erie Lackawanna had to maintain service on these lines. Mergers between railroads were seen as a way to curtail these issues by combining capital and services and creating efficiencies. In 1968, following the Erie Lackawanna's example, the NYC and its rival the Pennsylvania Railroad formed Penn Central Transportation with the hope of revitalizing their fortunes. In 1969 the bankrupt NYNH&H was also combined into Penn Central by the Interstate Commerce Commission. However, this merger eventually failed, due to large financial costs, government regulations, corporate rivalries, and lack of a formal merger plan. In 1970 Penn Central declared bankruptcy, at the time the largest corporate bankruptcy ever declared.[10] That same year, The Metropolitan Transportation Authority signed a contract to provide subsidies for these lines with Penn Central operating them. The state of Connecticut also provided subsidies in an operating agreement with the MTA to continue operations to New Haven, New Canaan, Danbury, and Waterbury.

In 1972, the bankrupt Penn Central petitioned the ICC to allow the discontinuance of its commuter services. Penn Central's long-distance passenger services had been taken over by the newly-formed, government-owned Amtrak a year earlier, and subsidies for the continuance of the New York-area lines would have to come from the states of New York and Connecticut.

Conrail

Many of the other Northeastern railroads, including the Erie Lackawanna, were following Penn Central into bankruptcy and the federal government decided to fold them into the newly created Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail) in 1976. Conrail was initially given the responsibility of operating the commuter services of these fallen railroads, including the Erie Lackawanna's and Penn Central's.

MTA operation and rebrand

Conrail was being floated by the federal government as a private for-profit freight-only carrier. Even with state subsidies, Conrail did not want the responsibility of taking on the operating costs of the commuter lines, which it was relieved from by the Northeast Rail Service Act of 1981. Thus, it became essential that state-owned agencies both operate and subsidize their commuter services. Over the next few years commuter lines under the control of Conrail were gradually taken over by state agencies such as the newly formed New Jersey Transit in New Jersey, the established SEPTA in southeastern Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority in Boston. The MTA in conjunction with the Connecticut Department of Transportation formed the Metro-North Commuter Railroad on January 1, 1983.[11]

Metro-North took over the former Erie Lackawanna services west of the Hudson and north of the New Jersey state line. Since those lines are physically connected to New Jersey Transit, operations were contracted to NJ Transit with Metro-North subsidizing the service and supplying equipment.

Much work was needed in reorganization, as significant business success would not appear for at least two decades, following the faltering railroad industry in the 1970s.[7] Conrail and later Metro-North had decided to trim whatever services they felt were unnecessary. A significant portion of the old NYC Harlem Line between Millerton and Chatham, New York was abandoned by Conrail leaving northeastern Dutchess and Columbia Counties with no rail transportation. Most commuter lines were kept in service although they were in much need of a repair.

The first major project undertaken by Metro-North was the extension of the third-rail electrification on the Harlem line from North White Plains to a new station at Brewster North (since renamed Southeast). This was completed in 1984.[12] During the late 1980s and early 1990s all wayside signals that did not protect switches and interlockings north of Grand Central Terminal were removed and replaced by modern cab signaling.

Metro-North spent the better part of its early days updating and repairing its infrastructure. Stations, track, and rolling stock all needed to be repaired, renovated, or replaced. The railroad succeeded and by the mid 90s gained both respect and monetary success, according to the MTA's website. 2006 was the best year for the division, with a 97.8% rate of on-time trains, record ridership (76.9 million people), and a passenger satisfaction rating of 92%.[7]

The Harlem and Hudson lines and the Park Avenue mainline to Grand Central are owned by Midtown TDR Ventures LLC, who bought them from the corporate successors to Penn Central,[13] but the MTA has a lease extending to 2274, and an option to buy starting in 2017.[14]

Infrastructure

East of Hudson

Propulsion systems

Most services running into Grand Central Terminal are electrically powered.

Diesel trains into Grand Central use General Electric P32AC-DM electro-diesel locomotives capable of switching to a pure electric mode. These locomotives have contact shoes compatible with Metro-North's under-running third rail power distribution system. Shoreliner series coaches are used in push-pull operation.

On the Hudson Line, local trains between Grand Central and Croton–Harmon are powered by third rail. Through trains to Poughkeepsie are diesel powered and do not require a change of locomotive at Croton-Harmon. The Harlem Line has third rail from Grand Central Terminal to Southeast and trains are powered by diesel north to Wassaic. At most times, passengers between Southeast and Wassaic must change at Southeast to a diesel train powered by Brookville BL20-GH locomotives. Electric service on the Hudson and Harlem lines uses M3 and M7 MU cars.

The New Haven Line is unique in that trains use both 750 V DC from a third rail and 12.5 kV AC from overhead catenary. The line from Woodlawn to Pelham, which is 3 miles (4.8 km), uses third rail, while the section from Pelham, New York east to New Haven Union Station, which is 58 miles (93 km), uses catenary. Multi-system M2, M4 and M6 railcars are used and new M8 railcars, of which 405 have been ordered; the first sets entered service in March 2011.

The New Canaan Branch also uses catenary. The Danbury Branch was electrified, but in 1961 became a diesel line. The Waterbury Branch, the only east-of-Hudson Metro-North service which has no direct service to Grand Central, is diesel only.

Power is collected from the bottom of the third rail as opposed to the top, used by other third rail systems, including the Long Island Rail Road and New York City Subway. This system is known as the Wilgus-Sprague third rail, and the SEPTA Market-Frankford Line in Philadelphia and Metro-North are the only two systems in North America that use it. It allows the third rail to be completely insulated from above, thus decreasing the chances of a person being electrocuted by coming in contact with the rail. It also reduces the impact of icing in winter.[15]

Signaling and safety appliances

The Hudson, Harlem and New Haven lines and the New Canaan branch and all passenger rolling stock is equipped with cab signalling, which displays the appropriate block signal in the engineer’s cab. All rolling stock is equipped with Automatic Train Control (ATC), which enforces the speed dictated by the cab signal by a penalty brake application should the engineer fail to obey it. There are no intermediate wayside signals between interlockings: operation is solely by cab signal. Wayside signals remain at interlockings.[16] These are a special type of signal, a go or a stop signal. They do not convey information about traffic in the blocks ahead - the cab signal conveys block information.[17]

Metro-North began upgrading its Operations Control Center in Grand Central Terminal in 2008, All control hardware was replaced. Software upgrades provide for state of the art rail traffic technology. Construction on a backup OCC was also underway. The new OCC at Grand Central opened over the weekend of July 18, 2010.[18]

West of Hudson

Most of the rolling stock on west-of-Hudson lines consists of Metro-North owned and marked Comet V cars, although occasionally other New Jersey Transit (NJT) cars are used as the two railroads pool equipment. The trains are also usually handled by EMD GP40FH-2, GP40PH-2, F40PH-3C, Alstom PL42AC, or Bombardier ALP-45DP locomotives, although any Metro-North or New Jersey Transit diesel can show up. Metro-North owned and marked equipment operated by NJ Transit can also be seen on other NJ Transit lines.

Reporting marks

Although Metro-North uses many abbreviations (MNCR, MNR, MN, etc.) the only official reporting marks registered and recognized on AEI scanner tags is 'MNCW'. Rolling stock owned by the Connecticut Department of Transportation bears the ConnDOT seal and either the New Haven ("NH") logo or the MTA logo and is identified using the reporting mark 'CNDX'.[19]

Rolling stock

The Metro-North Railroad uses an electric fleet of M2, M3A, M7A, M8, and, in the future, M9A railcars. Multiple Diesel locomotives and push-pull coaches are in use as well.

Fare policies

Metro-North offers many different ticket types and prices depending on the frequency of travel and distance of the ride. While the fare policies of the east of Hudson and west of Hudson divisions are essentially the same, west of Hudson trains are operated by New Jersey Transit using its ticketing system.

East of Hudson

Tickets may be bought from a ticket office at stations, ticket vending machines (TVMs), online through the "WebTicket" program or through apps for iOS and Android devices,[20] or on the train. Monthly tickets may be bought through the MTA's "Mail&Ride" program where monthly passes are delivered by mail. There is a discount for buying tickets online and through Mail&Ride. A surcharge is added if a ticket is purchased on a train.

Ticket types available include One-Way, Round-trip (two one-way tickets), 10-trip, Weekly (unlimited travel for one calendar week), Monthly (unlimited travel for one calendar month), and special student and disabled fare tickets. MetroCards are available on the reverse side of the weekly, monthly, and round-trip tickets.

All tickets to/from Manhattan (Grand Central Terminal and Harlem–125th Street) are distinguished as being peak or off-peak. Peak fares, substantially higher than off-peak, apply to trains that arrive in Grand Central between 5 AM and 10 AM and leave between 5:30 AM and 9 AM and 4 PM and 8 PM. Trains arriving at Grand Central during the PM peak are not subject to peak fares. Off-peak fares are charged all other times including weekends and holidays. Tickets for travel outside Manhattan are called "intermediate" tickets and the peak/off-peak rules do not apply.

The fares are distinguished by the 14 zones that the lines are divided into within New York State. In Connecticut, the fare structure is more complex due to the many branches on the New Haven line. Generally, these zones correspond to express stops on the lines and from "blocks" of service within the schedules.

On weekends, the railroad offers a special reduced-fare CityTicket, introduced in 2004,[21] for passengers who travel within New York City. It can be used for trips on Hudson Line and Harlem Line trains in the Bronx and Manhattan. It is not valid on New Haven Line trains between Manhattan and Fordham, as trips between those stations are not permitted on that line.

West of Hudson

All West of Hudson stations are included in New Jersey Transit's fare structure, and a single ticket may be purchased for travel between any two stations on either system.

Plans

Metro-North is continually upgrading trackage, equipment, and station facilities.[22]

East of Hudson

Hudson Line

On May 23, 2009, Yankees–East 153rd Street, a station with direct game-day trains from all East of Hudson lines, opened.[23] Trains from the New Haven and Harlem lines gain access via the wye at Mott Haven Junction, the first time that scheduled revenue service has operated across this section of the wye.

Northward expansion of the Hudson Line has often met opposition from residents of communities including Hyde Park and Rhinecliff, even though the latter is home to Amtrak's Rhinecliff-Kingston station, frequented by commuters from northern Dutchess and northern Ulster Counties.[24] Supervisors of some towns north of Poughkeepsie began in 2007 to express interest in extending rail service.[25]

Harlem Line

There are plans to redevelop the former Wingdale Psychiatric Center into a mixed-use commercial and residential neighborhood known as Dover Knolls, centered around the Harlem Valley–Wingdale Station.

Northward expansion took place most recently when it was extended from Dover Plains to Wassaic in 2000, requiring a costly rebuilding of tracks that had been abandoned years before. Going further north would require substantial investment to rebuild tracks, grade crossings, stations and other facilities that were removed long ago, and obtaining eminent domain for the train property used by the Harlem Valley Rail Trail. Expansion of either line would probably be limited to Dutchess County, as extending Metro-North into Columbia County, and thus to Chatham, would require changes to the MTA charter, and residents of that county would become subject to the MTA tax.

In 2014, Metro-North officials announced that they would be installing security cameras at all stations on the Harlem and New Haven lines in order to address public safety concerns.[26] These concerns arose from an incident on September 29, 2013, where the body of 17-year-old Mount Saint Michael Academy student Matthew Wallace was found on the tracks of the Wakefield station. Wallace, who was inebriated at the time, was killed when a northbound train struck him while he standing on the platform. Due to the lack of cameras at the station, footage of his death did not exist.[26]

New Haven Line

Discussions are underway to re-electrify the Danbury Branch[27] with a concurrent expansion to New Milford. Connecticut officials and Metro-North also began construction of a new station in West Haven in November 2010. It was opened on August 18, 2013.[28] ConnDOT is also moving forward on a study to increase freight service on the New Haven Line in an effort to reduce the number of trucks on the congested Connecticut Turnpike. A number of projects are either planned or underway that will upgrade the catenary system, replace outdated bridges, and straighten certain sections of the New Haven Line to accommodate the Acela's 240 km/h (150 mph) maximum operating speeds.[29] Metro-North has upgraded most of the original 1907–1914 New Haven Railroad catenary system, a project begun in the early 1990s and scheduled to finish in mid-2018.[30] The Danbury Branch is to receive $30 million for station upgrades along the line as well as implementation of a new signal system.

Plans to extend the Waterbury Branch northeast from Waterbury are under discussion. The extension would bring passenger rail service to central Connecticut, including the two largest cities in Connecticut without passenger rail service, Bristol and New Britain, and on to Hartford, where transfers to Amtrak would be possible.

In 2014, Metro-North officials announced that they would be installing security cameras at all stations on the Harlem and New Haven lines in order to address public safety concerns.[26]

Penn Station Access

In September 2009, Metro-North announced plans for a $1.7 million Environmental Impact Statement on accessing Penn Station; although this possibility had been considered for several decades, it was never pursued it because there was no space for any more trains at Penn Station.[31] The project depends upon the completion of East Side Access, which will redirect some Long Island Rail Road trains from Penn Station to Grand Central[31] upon its completion in December 2022.[32] Weekday Metro-North service in the Bronx includes 253 daily trains with approximately 13,200 daily boardings. In addition, Metro-North also connects 5,000 Bronx residents to suburban jobs, making it the largest rail reverse-commute market in the United States.[33] Governor Andrew Cuomo publicly and strongly supported the project in January 2014.[34]

New Haven Line trains would enter the Hell Gate Line through New Rochelle. At Sunnyside Yards, they would enter Manhattan via the East River Tunnels. Stations would be built at Co-op City, Morris Park, Parkchester/Van Nest,[35] and Hunts Point.[33] Open houses were held at each of the four proposed stations in the Fall of 2012.[31][33] Stations would be wheelchair-accessible, with bicycle parking and multi-modal transfer areas to train or bus.[33] Cuomo endorsed the New Haven Line portion of the Penn Station Access project in his 2014 State of the State speech, stating that some Sandy recovery money could pay for the project's cost of over $1 billion. He did not mention the Hudson Line portion of the project.[36]

Hudson Line trains would access Penn Station via a change at Spuyten Duyvil and would travel under Riverside Park via Amtrak's Empire Connection. Named Penn Station Access, the Hudson line plans call for new stations on West 125th Street in Harlem, Manhattan,[37] and West 62nd Street in Riverside South, Manhattan.[38]

On October 28, 2015, the MTA Board of Directors approved a 2015–2019 Capital Program which included $695 million in planned spending for the Penn Station Access project.[39] Upon completion of the Environmental Review process, Metro-North will design and implement the track and structural work needed to operate on the Hell Gate Bridge and its approaches in the Bronx and Queens; communications and signals work; power improvements, including third rail, power substations, and catenary; construction of the four stations in the Bronx; and rolling stock specification development for the fleet needed to operate the service.[40]

West of Hudson

The MTA is working with the Tappan Zee Bridge Environmental Review on several options where a future replacement for the Tappan Zee Bridge would include a rail line to connect the Port Jervis Line in Rockland County to the Hudson Line in Westchester County. "Alternatives 4A, 4B and 4C" all include plans for such a rail line to connect with the Hudson Line at Tarrytown, providing a one-seat ride from Rockland County to Grand Central Terminal in New York City. All three also include mass-transit service across Westchester County, connecting to the Harlem Line in White Plains, and the New Haven Line at Port Chester. The only difference between the three is whether the cross-Westchester trip will be accomplished by heavy rail, light rail or rapid bus service.[41]

Metro-North is considering extending Port Jervis Line service to Stewart International Airport in Newburgh,[42] a move that could make a Tappan Zee Bridge rail line even more useful, as it would serve both commuters and travelers who choose to fly to and from Stewart, instead of the three major New York City-area airports.

Community relations

Metro-North sponsors a mascot named Metro-Man, a small remote-operated robot that "speaks" about rail safety during appearances at schools and other events.[43]

Until 2009, an open house took place one Saturday in October at the Croton-Harmon heavy repair facility located next to the station. An extensive tour of the facility was given showing all facets of repair and maintenance along with detailed exhibits that display the different parts of the system such as power and signaling. Also a large display of the many diesel locomotives is set up and a free "Fall Foliage" ride is offered from the shop north to the interlocking south of Garrison station and back. In addition, the MTA Police have a display of their equipment and the K-9 dog corps put on a show so the visitors can see how highly skilled dogs can sniff out contraband and explosives. No open house has been held since then due to construction at the shop.[44]

In popular culture

The railroad has been featured in several films, including Hello Dolly!,[45] The Ice Storm, U.S. Marshals, Another Earth,[46] The Girl on the Train, Michael Jackson's short film for Bad, and Steven Spielberg's 2005 remake of War of the Worlds.

Major accidents

- On February 3, 2015, at about 6:30 PM EST, a train on the Harlem Line hit a sports utility vehicle at a railroad crossing in Valhalla, New York, killing its 49-year-old driver Ellen Brody instantly upon impact. The fuel tank of the car was ruptured, causing the car and the train to catch on fire, after the electrified and live 700 volt DC underrunning third rail was pulled up and punctured through the roof of the first 2 cars (numbers 4333/4332). The accident killed six people, injured 12, and forced the evacuation of hundreds of people aboard the train. The National Transportation Safety Board is leading an investigation of the accident.[47]

- On December 1, 2013, at 7:19 AM EST,[48] seven passenger cars and a diesel locomotive from Poughkeepsie to Grand Central Terminal derailed in the Spuyten Duyvil section of the Bronx, killing four people and injuring 65, 12 of them critically. At least three cars out of seven were flipped over on their sides.[49] The train was traveling into the curve at an excessive speed of 82 mph in a 30 mph curve. Amtrak Empire Line service was halted until 3:00 PM,[50][51] and Hudson Line service was suspended until December 4.[52]

- On May 17, 2013, at 6:01 PM EDT during the evening rush hour, two trains collided when an eastbound train derailed in Bridgeport, Connecticut just east of the Fairfield Metro station blocking the adjacent track just as a westbound train passed traveling in the opposite direction. At least sixty passengers were injured, including five with critical injuries. It also caused a major disruption to other rail service in the Northeast Corridor. Amtrak halted all service between New York City and Boston.[53]

- On April 6, 1988, at 7:59 AM, a northbound Metro-North train collided with another Metro-North train in Mount Vernon, New York, resulting in the death of an engineer. Both trains were empty at the time of the collision.[54]

- On February 17, 1987, at about 7:05 PM, a slowly moving 14-car Metro-North Hudson Line train collided with an empty Metro-North train returning to Grand Central on an elevated stretch of tracks at 140th Street and Park Avenue in the Bronx. Twenty passengers were injured in the accident, none of them seriously.[55]

See also

- Long Island Rail Road

- List of Metro-North Railroad stations

- Grand Central Terminal

- Transportation in New York City

- Transportation in New York State

References

- ↑ "Transit Ridership Report Fourth Quarter and End-of-Year 2014" (pdf). American Public Transportation Association (APTA). March 3, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ↑ "MTA - Transportation Network". mta.info.

- ↑ "MNR About MNR". web.mta.info. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ↑ "MTA Metro-North Railroad". Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Years Ended December 31, 2012 and 2011" (pdf). Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). June 21, 2013. p. 147. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ↑ Metro-North map

- 1 2 3 Railhistory

- ↑ Hyatt, Elijah Clarence (1898). History of the New York & Harlem Railroad.

- ↑ History of the NHRR. Nhrhta.org (January 1, 1969). Retrieved on 2013-07-26.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Penn Central | Penn Central Railroad Historical Society". www.pcrrhs.org. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ↑ Goldman, Ari L. (July 25, 1983). "Metro-North Acts on Improvements". The New York Times.

- ↑ Hudson, Edward (January 1, 1984). "ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT NEARS COMPLETION ON HARLEM LINE". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ↑ "37587 - Decision". Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ↑ Weiss, Lois (July 6, 2007). "Air Rights Make Deals Fly". New York Post. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ↑ Middleton, William D. (September 4, 2002). "Railroad Standardization - Notes on Third Rail Electrification" (PDF). Railway & Locomotive Historical Society Newsletter. 27 (4): 10–11. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ↑ Metro North Railroad Employees Timetable Effective February 27, 2011.

- ↑ Metro North Operating Rules Effective February 27, 2011.

- ↑ We are total control freaks, Metro North, September 2010

- ↑ "AAR Reporting Marks". February 3, 2012.

- ↑ "MTA eTix Ticketing App Available on LIRR & Metro-North". Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- ↑ "CityTicket Begins Tomorrow on LIRR And Metro-North" (Press release). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. January 9, 2004. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ↑ "MTA Service Updates".

- ↑ "MTA | Press Release | Metro-North | Train Service to MTA Metro-North Railroad's Newest Station Yankees – E. 153rd Street Begins Saturday May 23, 2009". www.mta.info. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ↑ C. J. Chivers (October 12, 1999). "Hudson Towns Wary of Rail's Reach; Commuter Line Extension Faces Hostility in Bucolic North Dutchess". The New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2007.

- ↑ United Transportation Union Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3

- "Parents of teen killed by Metro-North train demand details on death". January 8, 2014. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- "Teen’s death on Metro-North tracks does not spawn change one year later". October 1, 2014. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- "Parents of Yonkers teen killed by train seek answers". Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ↑ "Danbury Branch Electrification Feasibility Study". www.DanburyBranchStudy.com. Connecticut Department of Transportation (ConnDOT). Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Our New West Haven Station Is Open For Business!". Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- ↑ http://web.mta.info/mnr/html/mileposts.pdf

- ↑ "New Haven Catenary Replacement Project Update (May 2017)". Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Cassidy, Martin B. (September 8, 2009). "Metro-North reviving Penn Station-New Haven Line plans". Connecticut Post. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ↑ "MTA Pushes Back Completion of East Side Access Project until 2019". NY1. May 9, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Penn Station Access Study. Mta.info. Retrieved on July 26, 2013.

- ↑ Flegenheimer, Matt (January 8, 2014). "Support for Metro-North Line in Bronx and to Penn Station". New York Times.

- ↑ "Bronx Neighbors Wants Future Metro-North Stop Named After Area's Distant Past". New York 1 News. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ↑ "From Albany, a Penn Station Access champion emerges :: Second Ave. Sagas". Secondavenuesagas.com. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- ↑ Namako, Tom (September 9, 2009). "Next Stop: Penn Sta.". New York Post. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ↑ "The Spirit - Your local paper for the Upper West Side". westsidespirit.com.

- ↑ "MTA Approves 2015-19 Capital Program to Renew, Enhance and Expand Mass Transit" (Press release). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 28, 2015.

- ↑ Metropolitan Transportation Authority (October 28, 2015). MTA Capital Program 2015-2019 (PDF). pp. 150–151, 223.

- ↑ Tappan Zee Bridge Environmental Review

- ↑ "MTA - Planning Studies". mta.info.

- ↑ "A Railroad Reborn: Metro-North At 25" (Press release). Metro-North Railroad. February 6, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Come One – Come All To Harmon Shops's Open House" (Press release). Metro-North Railroad. September 25, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

- ↑ "The Great Movie Musical Trivia Book". google.com.

- ↑ Chen, Jialu (July 24, 2011). "'Another Earth' presents worlds of possibilities". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ Fitsimmons, Emma (February 4, 2015). "Metro-North Train Hits S.U.V.; Federal Officials Prepare to Investigate". The New York Times. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Governor: 4 dead, 63 hurt in NYC train derailment". The Boston Herald. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Metro-North train derails in Bronx area of New York City". BBC News Online. December 1, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Metro-North derailment leaves 4 dead, dozens injured". ABC News 7. ABC.com. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Amtrak Trains From NYC to Albany Back in Service". ABC News. ABC News. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Service restored to affected Hudson Line". myfoxny.com. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ↑ Flegenheimer, Matt; Davey, Robert (May 17, 2013). "Metro-North Trains Collide in Connecticut; Dozens of Injuries Are Reported". The New York Times.

- ↑ Feron, James (April 7, 1988). "Metro-North Engineer Dies In Crash of 2 Empty Trains". The New York Times. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ↑ Barron, James (February 18, 1987). "2 Trains Collide in South Bronx; 20 are Injured". The New York Times. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Metro-North Railroad. |

- Official website

- Metro-North Railroad system map

- Metro-North Railroad Commuter Council

- Connecticut Commuter Rail Council

- Metro-North Railroad Special Investigation - National Transportation Safety Board