Metric system

The metric system is an internationally agreed decimal system of measurement. It was originally based on the mètre des Archives and the kilogramme des Archives introduced by the French First Republic in 1799,[1] but over the years the definitions of the metre and the kilogram have been refined, and the metric system has been extended to incorporate many more units. Although a number of variants of the metric system emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the term is now often used as a synonym for "SI"[Note 1] or the "International System of Units"—the official system of measurement in almost every country in the world.

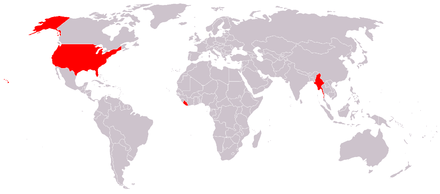

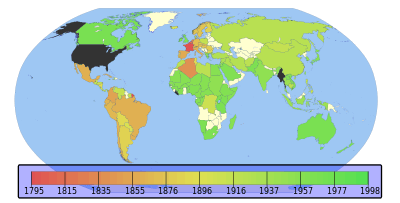

The metric system has been officially sanctioned for use in the United States since 1866,[2] but the U.S. remains the only industrialised country that has not fully adopted the metric system as its official system of measurement, although, in 1988, the United States Congress passed the Omnibus Foreign Trade and Competitiveness Act, which designates "the metric system of measurement as the preferred system of weights and measures for U.S. trade and commerce". Among many other things, the act requires federal agencies to use metric measurements in nearly all of its activities, although there are still some exceptions allowing traditional linear units to be used in documents intended for consumers. Many sources also cite the countries of Liberia and Myanmar (Burma) as the only other countries not to have done so. Although the United Kingdom also uses the metric system for most administrative and trade purposes, imperial units are widely used by the public and are permitted or obligatory for some purposes, such as road signs.

Although the originators intended to devise a system that was equally accessible to all, it proved necessary to use prototype units in the custody of national or local authorities as standards. Control of the prototype units of measure was maintained by the later French governments until 1875, when it was passed to an international intergovernmental organisation, the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM).[Note 1]

From its beginning, the main features of the metric system were the standard set of interrelated base units and a standard set of prefixes in powers of ten. These base units are used to derive larger and smaller units that could replace a huge number of other units of measure in existence. Although the system was first developed for commercial use, the development of coherent units of measure made it particularly suitable for science and engineering.

The uncoordinated use of the metric system by different scientific and engineering disciplines, particularly in the late 19th century, resulted in different choices of base units even though all were based on the same definitions of the units of the metre and the kilogram. During the 20th century, efforts were made to rationalise these units, and in 1960, the CGPM published the International System of Units, which has since then been the internationally recognised standard metric system.

Features

Although the metric system has changed and developed since its inception, its basic concepts have hardly changed. Designed for transnational use, it consisted of a basic set of units of measurement, now known as base units. Derived units were built up from the base units using logical rather than empirical relationships while multiples and submultiples of both base and derived units were decimal-based and identified by a standard set of prefixes.

Universality

At the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, most countries and even some cities had their own system of measurement. Although different countries might have used units of measure with the same name, such as the foot, or local language equivalents such as pied, Fuß, and voet, there was no consistency in the magnitude of those units, nor in the relationships with their multiples and submultiples,[3] much like the modern-day differences between the US and the UK pints and gallons.[4]

The metric system was designed to be universal—in the words of the French philosopher Marquis de Condorcet it was to be "for all people for all time".[1]:1 It was designed for ordinary people, for engineers who worked in human-related measurements and for astronomers and physicists who worked with numbers both small and large, hence the huge range of the prefixes that have been defined in SI.[5]

When the French Government first investigated the idea of overhauling their system of measurement, the concept of universality was put into practice in 1789: Maurice de Talleyrand, acting on Condorcet's advice, invited John Riggs Miller, a British parliamentarian and Thomas Jefferson, the American Secretary of State to George Washington, to work with the French in producing an international standard by promoting legislation in their respective legislative bodies. However, these early overtures failed and the custody of the metric system remained in the hands of the French government until 1875.[1]:250–253

In languages where the distinction is made, unit names are common nouns (i.e. not proper nouns). They use the character set and follow the grammatical rules of the language concerned, for example "kilomètre", "kilómetro", but each unit has a symbol that is independent of language, for example "km" for "kilometre", "V" for "volts" etc.[6]

Decimal multiples

In the metric system, multiples and submultiples of units follow a decimal pattern,[Note 2] a concept identified as a possibility in 1586 by Simon Stevin, the Flemish mathematician who had introduced decimal fractions into Europe.[7] This is done at the cost of losing the simplicity associated with many traditional systems of units where division by 3 does not result in awkward fractions; for example one third of a foot is four inches, a simplicity that in 1790 was debated, but rejected by the originators of the metric system.[8] In 1854, in the introduction to the proceedings of the [British] Decimal Association, the mathematician Augustus de Morgan summarised the advantages of a decimal-based system over a non-decimal system thus: "In the simple rules of arithmetic, we practice a pure decimal system, nowhere interrupted by the entrance of any other system: from column to column we never carry anything but tens".[9]

| Metric prefixes in everyday use | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Text | Symbol | Factor | Power |

| exa | E | 1000000000000000000 | 1018 |

| peta | P | 1000000000000000 | 1015 |

| tera | T | 1000000000000 | 1012 |

| giga | G | 1000000000 | 109 |

| mega | M | 1000000 | 106 |

| kilo | k | 1000 | 103 |

| hecto | h | 100 | 102 |

| deca | da | 10 | 101 |

| (none) | (none) | 1 | 100 |

| deci | d | 0.1 | 10−1 |

| centi | c | 0.01 | 10−2 |

| milli | m | 0.001 | 10−3 |

| micro | μ | 0.000001 | 10−6 |

| nano | n | 0.000000001 | 10−9 |

| pico | p | 0.000000000001 | 10−12 |

| femto | f | 0.000000000000001 | 10−15 |

| atto | a | 0.000000000000000001 | 10−18 |

A common set of decimal-based prefixes that have the effect of multiplication or division by an integer power of ten can be applied to units that are themselves too large or too small for practical use. The concept of using consistent classical (Latin or Greek) names for the prefixes was first proposed in a report by the [French Revolutionary] Commission on Weights and Measures in May 1793.[1]:89–96 The prefix kilo, for example, is used to multiply the unit by 1000, and the prefix milli is to indicate a one-thousandth part of the unit. Thus the kilogram and kilometre are a thousand grams and metres respectively, and a milligram and millimetre are one thousandth of a gram and metre respectively. These relations can be written symbolically as:[5]

- 1 mg = 0.001 g

- 1 km = 1000 m

In the early days, multipliers that were positive powers of ten were given Greek-derived prefixes such as kilo- and mega-, and those that were negative powers of ten were given Latin-derived prefixes such as centi- and milli-. However, 1935 extensions to the prefix system did not follow this convention: the prefixes nano- and micro-, for example have Greek roots.[10] During the 19th century the prefix myria-, derived from the Greek word μύριοι (mýrioi), was used as a multiplier for 10000.[11]

When applying prefixes to derived units of area and volume that are expressed in terms of units of length squared or cubed, the square and cube operators are applied to the unit of length including the prefix, as illustrated below.[5]

1 mm2 (square millimetre) = (1 mm)2 = (0.001 m)2 = 0.000001 m2 1 km2 (square kilometre) = (1 km)2 = (1000 m)2 = 1000000 m2 1 mm3 (cubic millimetre) = (1 mm)3 = (0.001 m)3 = 0.000000001 m3 1 km3 (cubic kilometre) = (1 km)3 = (1000 m)3 = 1000000000 m3

Prefixes are not usually used to indicate multiples of a second greater than 1; the non-SI units of minute, hour and day are used instead. On the other hand, prefixes are used for multiples of the non-SI unit of volume, the litre (l, L) such as millilitres (ml).[5]

Realisability and replicable prototypes

The base units used in the metric system must be realisable, ideally with reference to natural phenomena rather than unique artefacts. Each of the base units in SI is accompanied by a mise en pratique [practical realisation] published by the BIPM that describes in detail at least one way in which the base unit can be measured.[12] Where possible, definitions of the base units were developed so that any laboratory equipped with proper instruments would be able to realise a standard without reliance on an artefact held by another country. In practice, such realisation is done under the auspices of a mutual acceptance arrangement (MAA).[13]

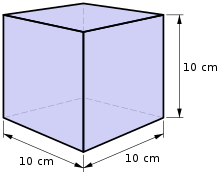

Metre and kilogram

In the original version of the metric system the base units could be derived from a specified length (the metre) and the weight [mass] of a specified volume ( 1⁄1000 of a cubic metre) of pure water. Initially the de facto French Government of the day, the Assemblée nationale constituante, considered defining the metre as the length of a pendulum that has a period of one second at 45°N and an altitude equal to sea level. The altitude and latitude were specified to accommodate variations in gravity; the specified latitude was a compromise between the latitude of London (51° 30'N), Paris (48° 50'N) and the median parallel of the United States (38°N) to accommodate variations.[1]:94 However the mathematician Borda persuaded the assembly that a survey having its ends at sea level and based on a meridian that spanned at least 10% of the earth's quadrant would be more appropriate for such a basis.[1]:96

The available technology of the 1790s made it impracticable to use these definitions as the basis of the kilogram and the metre, so prototypes that represented these quantities insofar as was practicable were manufactured. On 22 June 1799 these prototypes were adopted as the definitive reference pieces, deposited in the Archives nationales and became known as the mètre des Archives and the kilogramme des Archives. Copies were made and distributed around France.[1]:266–269 These artefacts were replaced in 1889 by the new prototypes manufactured under international supervision. Insofar as was possible, the new prototypes were exact copies of the original prototypes, but used a later technology to ensure better stability. One of each of the kilogram and metre prototypes were chosen by lot to serve as the definitive international reference piece with the remainder being distributed to signatories of the Metre Convention.[15] In 1889 there was no generally accepted theory regarding the nature of light but by 1960 the wavelength of specific light spectra could give a more accurate and reproducible value than a prototype metre. In that year the prototype metre was replaced by a formal definition that defines the metre in terms of the wavelength of specified light spectra. By 1983 it was accepted that the speed of light in vacuum was constant and that this constant provided a more reproducible procedure for measuring length. Therefore, the metre was redefined in terms of the speed of light. These definitions give a much better reproducibility and also allow anyone, anywhere with a suitably equipped laboratory, to make a standard metre.[16]

Other base units

None of the other base units rely on a prototype – all are based on phenomena that are directly observable and had been in use for many years before formally becoming part of the metric system.

The second first became a de facto base unit within the metric system when, in 1832, Carl Friedrich Gauss used it, the centimetre and the gram to derive the units associated with values of absolute measurements of the Earth's magnetic field.[17] The second, if based on the Earth's rotation, is not a constant as the Earth's rotation is slowing down—in 2008 the solar day was 0.002 s longer than in 1820.[18] This had been known for many years; consequently in 1952 the International Astronomical Union (IAU) defined the second in terms of the Earth's rotation in the year 1900. Measurements of time were made using extrapolation from readings based on astronomy. With the launch of SI in 1960, the 11th CGPM adopted the IAU definition.[19] In the years that followed, atomic clocks became significantly more reliable and precise; and in 1968 the 13th CGPM redefined the second in terms of a specific frequency from the emission spectrum of the caesium 133 atom, a component of atomic clocks. This provided the means to measure the time associated with astronomical phenomena rather than using astronomical phenomena as the basis from which time measurements were made.[20][21]

The CGS absolute unit of electric current, the abampere, had been defined in terms of the force between two parallel current-carrying wires in 1881.[22] In the 1940s, the International Electrotechnical Commission adopted an MKS variant of this definition for the ampere, which was adopted in 1948 by the CGPM.[23][24]

Temperature has always been based on observable phenomena—in 1744 the degree Centigrade[Note 3] was based on the freezing and boiling points of water.[25] In 1948 the CGPM adopted the Centigrade scale, renamed it the "Celsius" temperature scale name and defined it in terms of the triple point of water.[26]

When the mole and the candela were accepted by the CGPM in 1971 and 1975 respectively, both had been defined by third parties by reference to phenomena rather than artefacts.[27]

Coherence

Each variant of the metric system has a degree of coherence—the various derived units are directly related to the base units without the need for intermediate conversion factors.[28] For example, in a coherent system the units of force, energy and power are chosen so that the equations

force = mass × acceleration energy = force × distance power = energy ÷ time

hold without the introduction of unit conversion factors. Once a set of coherent units have been defined, other relationships in physics that use those units will automatically be true. Therefore, Einstein's mass-energy equation, E = mc2, does not require extraneous constants when expressed in coherent units.[29]

The CGS system had two units of energy, the erg that was related to mechanics and the calorie that was related to thermal energy; so only one of them (the erg) could bear a coherent relationship to the base units. Coherence was a design aim of SI resulting in only one unit of energy being defined – the joule.[20]

In SI, which is a coherent system, the unit of power is the "watt", which is defined as "one joule per second".[20] In the US customary system of measurement, which is non-coherent, the unit of power is the "horsepower", which is defined as "550 foot-pounds per second" (the pound in this context being the pound-force).[30] Similarly, neither the US gallon nor the imperial gallon is one cubic foot or one cubic yard— the US gallon is 231 cubic inches and the imperial gallon is 277.42 cubic inches.[31]

The concept of coherence was only introduced into the metric system in the third quarter of the 19th century;[32] in its original form the metric system was non-coherent—in particular the litre was 0.001 m3 and the are (from which the hectare derives) was 100 m2. However the units of mass and length were related to each other through the physical properties of water, the gram having been designed as being the mass of one cubic centimetre of water at its freezing point.[33]

History

In 1585 the Flemish mathematician Simon Stevin published a small pamphlet called De Theinde ("the tenth"). Decimal fractions had been employed for the extraction of square roots some five centuries before his time, but nobody used decimal numbers in daily life. Stevin declared that using decimals was so important that the universal introduction of decimal weights, measures and coinage was only a matter of time.[7]

One of the earliest proposals for a decimal system in which length, area, volume and mass were linked to each other was made by John Wilkins, first secretary of the Royal Society of London in his 1668 essay "An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language". His proposal used a pendulum that had a beat of one second as the basis of the unit of length.[34][35][36] Two years later, in 1670, Gabriel Mouton, a French abbot and scientist, proposed a decimal system of length based on the circumference of the Earth. His suggestion was that a unit, the milliare, be defined as a minute of arc along a meridian. He then suggested a system of sub-units, dividing successively by factors of ten into the centuria, decuria, virga, virgula, decima, centesima, and millesima. His ideas attracted interest at the time, and were supported by both Jean Picard and Christiaan Huygens in 1673, and also studied at the Royal Society in London. In the same year, Gottfried Leibniz independently made proposals similar to those of Mouton.[37]

In pre-revolutionary Europe, each state had its own system of units of measure.[3] Some countries, such as Spain and Russia, saw the advantages of harmonising their units of measure with those of their trading partners.[38] However, vested interests who profited from variations in units of measure opposed this. This was particularly prevalent in France where the huge inconsistency in the size of units of measure was one of the causes that, in 1789, led to the outbreak of the French Revolution.[1]:2 During the early years of the revolution, savants[Note 4] including the Marquis de Condorcet, Pierre-Simon Laplace, Adrien-Marie Legendre, Antoine Lavoisier and Jean-Charles de Borda set up a Commission of Weights and Measures. The commission was of the opinion that the country should adopt a completely new system of measure based on the principles of logic and natural phenomena.[39] Logic dictated that such a system should be based on the radix used for counting. Their report of March 1791 to the Assemblée nationale constituante considered but rejected the view of Laplace that a duodecimal system of counting should replace the existing decimal system; the view such a system was bound to fail prevailed. The commission's final recommendation was that the assembly should promote a decimal-based system of measurement. The leaders of the assembly accepted the views of the commission.[1]:99–100[8]

Initially France attempted to work with other countries towards the adoption of a common set of units of measure.[1]:99–100 Among the supporters of such an international system of units was Thomas Jefferson who, in 1790, presented a document Plan for Establishing Uniformity in the Coinage, Weights, and Measures of the United States to Congress in which he advocated a decimal system that used traditional names for units (such as ten inches per foot).[40] The report was considered but not adopted by Congress.[1]: 249–250

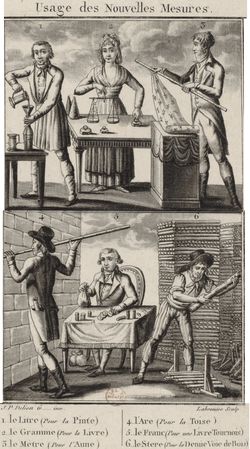

Original metric system

The French law of 18 Germinal, Year III (7 April 1795) defined five units of measure:[33]

- The mètre for length

- The are (100 m2) for area [of land]

- The stère (1 m3) for volume of stacked[41] firewood

- The litre (1 dm3) for volumes of liquid

- The gramme for mass.

This system continued the tradition of having separate base units for geometrically related dimensions, e.g., mètre for lengths, are (100 m2) for areas, stère (1 m3) for dry capacities, and litre (1 dm3) for liquid capacities. The hectare, equal to a hundred ares, the area of a square 100 metres on a side (about 2.47 acres), is still in use. The early metric system included only a few prefixes from milli (one thousandth) to myria (ten thousand).[33]

Originally the kilogramme, defined as being one pinte (later renamed the litre) of water at the melting point of ice, was called the grave;[14] the gramme being an alternative name for a thousandth of a grave. However, the word grave, being a synonym for the title "count", had aristocratic connotations and was renamed the kilogramme. The name mètre was suggested by Auguste-Savinien Leblond in May 1790.[1]: 92

France officially adopted the metric system on 10 December 1799. Although it was decreed that its use was to be mandatory in Paris that year and across the provinces the following year, the decree was not universally observed across France.[42]

International adoption

Areas annexed by France during the Napoleonic era were the first to inherit the metric system. In 1812, Napoleon introduced a system known as mesures usuelles, which used the names of pre-metric units of measure, but defined them in terms of metric units – for example, the livre metrique (metric pound) was 500 g and the toise metrique (metric fathom) was 2 metres.[43] After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, France lost the territories that she had annexed; some, such as the Papal States reverted to their pre-revolutionary units of measure, others such as Baden adopted a modified version of the mesures usuelles, but France kept her system of measurement intact.[44]

In 1817, the Netherlands reintroduced the metric system, but used pre-revolutionary names—for example 1 centimetre became the duim (thumb), the ons (ounce) became 100 g and so on.[45] Certain German states adopted similar systems[44][46] and in 1852 the German Zollverein (customs union) adopted the zollpfund (customs pound) of 500 g for intrastate commerce.[47] In 1872 the newly formed German Empire adopted the metric system as its official system of weights and measures[48] and the newly formed Kingdom of Italy likewise, following the lead given by Piedmont, adopted the metric system in 1861.[49]

The Exposition Universelle (1867) (Paris Exhibition) devoted a stand to the metric system and by 1875, two thirds of the European population and close to half the world's population had adopted the metric system. By 1872, the only principal European countries not to have adopted the metric system were Russia and the United Kingdom.[50]

By 1920, countries comprising 22% of the world's population, mainly English-speaking, used the imperial system or the closely related US customary system; 25% used mainly the metric system and the remaining 53% used neither.[42]

In 1927, several million people in the United States sent over 100,000 petitions backed by the Metric Association and The General Federation of Women's Clubs urging Congress to adopt the metric system. The petition was opposed by the manufacturing industry, citing the cost of the conversion.[51]

International standards

In 1861 a committee of the British Association for Advancement of Science (BAAS) including William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin), James Clerk Maxwell and James Prescott Joule introduced the concept of a coherent system of units based on the metre, gram and second, which, in 1873, was extended to include electrical units.[52][53]

On 20 May 1875 an international treaty known as the Convention du Mètre (Metre Convention)[54] was signed by 17 states. This treaty established the following organisations to conduct international activities relating to a uniform system for measurements:[55]

- General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM),[Note 1] an intergovernmental conference of official delegates of member nations and the supreme authority for all actions;

- International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM),[Note 1] consisting of selected scientists and metrologists, which prepares and executes the decisions of the CGPM and is responsible for the supervision of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM);

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM),[Note 1] a permanent laboratory and world centre of scientific metrology, the activities of which include the establishment of the basic standards and scales of the principal physical quantities and maintenance of the international prototype standards.

In 1881 first International Electrical Congress adopted the BAAS recommendations on electrical units, followed by a series of congresses in which further units of measure were defined and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) was set up with the specific task of overseeing electrical units of measure.[56] This was followed by the International Congress of Radiology (ISR) who, at their inaugural meeting in 1926, initiated the definition of radiological-related units of measure.[57] In 1921 the Metre Convention was extended to cover all units of measure, not just length and mass and in 1933 the 8th CGPM resolved to work with other international bodies to agree standards for electrical units that could be related back to the international prototypes.[58] Since 1954 the CIPM committee that oversees the definition of units of measurement, the Consultative Committee for Units,[Note 5] has representatives from many international organisations including the ISR, IEC and ISO under the chairmanship of the CIPM.[59]

Variants

A number of variants of the metric system evolved, all using the Mètre des Archives and Kilogramme des Archives (or their descendants) as their base units, but differing in the definitions of the various derived units.

| Variants of the metric system | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Centimetre-gram-second systems

The centimetre gram second system of units (CGS) was the first coherent metric system, having been developed in the 1860s and promoted by Maxwell and Thomson. In 1874, this system was formally promoted by the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS).[17] The system's characteristics are that density is expressed in g/cm3, force expressed in dynes and mechanical energy in ergs. Thermal energy was defined in calories, one calorie being the energy required to raise the temperature of one gram of water from 15.5 °C to 16.5 °C. The meeting also proposed two sets of units for electrical and magnetic properties – the electrostatic set of units and the electromagnetic set of units.[60]

Metre-kilogram-second systems

The CGS units of electricity were cumbersome to work with. This was remedied at the 1893 International Electrical Congress held in Chicago by defining the "international" ampere and ohm using definitions based on the metre, kilogram and second.[61] In 1901, Giovanni Giorgi showed that by adding an electrical unit as a fourth base unit, the various anomalies in electromagnetic systems could be resolved. The metre-kilogram-second-coulomb (MKSC) and metre-kilogram-second-ampere (MKSA) systems are examples of such systems.[62]

The International System of Units (Système international d'unités or SI) is the current international standard metric system and is also the system most widely used around the world. It is an extension of Giorgi's MKSA system—its base units are the metre, kilogram, second, ampere, kelvin, candela and mole.[20]

Metre-tonne-second systems

The metre-tonne-second system of units (MTS) was based on the metre, tonne and second – the unit of force was the sthène and the unit of pressure was the pièze. It was invented in France for industrial use and from 1933 to 1955 was used both in France and in the Soviet Union.[56][63]

Gravitational systems

Gravitational metric systems use the kilogram-force (kilopond) as a base unit of force, with mass measured in a unit known as the hyl, Technische Mass Einheit (TME), mug or metric slug.[64] Although the CGPM passed a resolution in 1901 defining the standard value of acceleration due to gravity to be 980.665 cm/s2, gravitational units are not part of the International System of Units (SI).[65]

International System of Units

The 9th CGPM met in 1948, three years after the end of the Second World War and fifteen years after the 8th CGPM. In response to formal requests made by the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics and by the French Government to establish a practical system of units of measure, the CGPM requested the CIPM to prepare recommendations for such a system, suitable for adoption by all countries adhering to the Metre Convention. The recommendation also catalogued symbols for the most important MKS and CGS units of measure and for the first time the CGPM made recommendations concerning derived units.[66] At the same time the CGPM formally adopted a recommendation for the writing and printing of unit symbols and of numbers.[67]

The CIPM's draft proposal, which was an extensive revision and simplification of the metric unit definitions, symbols and terminology based on the MKS system of units, was put to the 10th CGPM in 1954. In accordance with Giorgi's proposals of 1901, the CIPM also recommended that the ampere be the base unit from which electromechanical units would be derived. The definitions for the ohm and volt that had previously been in use were discarded and these units became derived units based on the metre, ampere, second and kilogram. After negotiations with the International Commission on Illumination (CIE)[Note 1] and IUPAP, two further base units, the degree kelvin and the candela were also proposed as base units.[68] The full system and name "Système International d'Unités" were adopted at the 11th CGPM in October 1960.[69] During the years that followed the definitions of the base units and particularly the methods of applying these definitions have been refined.[70]

The formal definition of International System of Units (SI) along with the associated resolutions passed by the CGPM and the CIPM are published by the BIPM in brochure form at regular intervals. The eighth edition of the brochure Le Système International d'Unités—The International System of Units was published in 2006 and is available on the internet.[71] In October 2011, at the 24th CGPM proposals were made to change the definitions of four of the base units. These changes should not affect the average person.[72]

Relating SI to the real world

Although SI, as published by the CGPM, should, in theory, meet all the requirements of commerce, science and technology, certain units of measure have acquired such a position within the world community that it is likely they will be used for many years to come. In order that such units are used consistently around the world, the CGPM catalogued such units in Tables 6 to 9 of the SI brochure. These categories are:[73]

- Non-SI units accepted for use with the International System of Units (Table 6). This list includes the hour and minute, the angular measures (degree, minute and second of arc) and the historic [non-coherent] metric units, the litre, tonne and hectare (originally agreed by the CGPM in 1879)

- Non-SI units whose values in SI units must be obtained experimentally (Table 7). This list includes various units of measure used in atomic and nuclear physics and in astronomy such as the dalton, the electron mass, the electron volt, the astronomical unit, the solar mass, and a number of other units of measure that are well-established, but dependent on experimentally-determined physical quantities.

- Other non-SI units (Table 8). This list catalogues a number of units of measure that have been used internationally in certain well-defined spheres including the bar for pressure, the ångström for atomic physics, the nautical mile and the knot in navigation.

- Non-SI units associated with the CGS and the CGS-Gaussian system of units (Table 9). This table catalogues a number of units of measure based on the CGS system and dating from the nineteenth century. They appear frequently in the literature, but their continued use is discouraged by the CGPM.

Usage around the world

The usage of the metric system varies around the world. According to the US Central Intelligence Agency's Factbook (2007), the International System of Units has been adopted as the official system of weights and measures by all nations in the world except for Myanmar (Burma), Liberia and the United States,[74] while the NIST has identified the United States as the only industrialised country where the metric system is not the predominant system of units.[75] However, reports published since 2007 hold this is no longer true of Myanmar or Liberia.[76] An Agence France-Presse report from 2010 stated that Sierra Leone had passed a law to replace the imperial system with the metric system thereby aligning its system of measurement with that used by its Mano River Union (MRU) neighbours Guinea and Liberia.[Note 6][77] Reports from Myanmar suggest that the country is also planning to adopt the metric system.[78]

In the United States metric units, authorised by Congress in 1866,[2] are widely used in science, medicine, military, and partially in industry, but customary units predominate in household use. At retail stores the litre is a commonly used unit for volume, especially on bottles of beverages, and milligrams are used to denominate the amounts of medications, rather than grains.[79][80] On the other hand, non-metric units are used in certain regulated environments such as nautical miles and knots in international aviation. Resistance to metrication, particularly in the UK and the US, has been connected to the perceived cost involved, a sense of patriotism and lack of desire to conform internationally.[81][82][83]

In the countries of the Commonwealth of Nations the metric system has replaced the imperial system by varying degrees: Australia, New Zealand and Commonwealth countries in Africa are almost totally metric, India is mostly metric while Canada is partly metric. In the United Kingdom, the metric system, the use of which was first permitted for trade in 1864, is used in much government business, in most industries including building, health and engineering and for pricing by measure or weight in most trading situations, both wholesale and retail.[84] However the imperial system is widely used by the British public, such as feet and inches as a measurement of height, weight in stone and pounds, and is legally mandated in various cases, such as road-sign distances, which must be given in yards and miles.[1][81][85] In 2007, the European Commission announced that it was to abandon the requirement for metric-only labelling on packaged goods in the UK, and to allow dual metric–imperial marking to continue indefinitely.[86]

Some other jurisdictions, such as Hong Kong, have laws mandating or permitting other systems of measurement in parallel with the metric system in some or all contexts.[87]

Variations in spelling

The SI symbols for the metric units are intended to be identical, regardless of the language used[6] but unit names are ordinary nouns and use the character set and follow the grammatical rules of the language concerned. For example, the SI unit symbol for kilometre is "km" everywhere in the world, even though the local language word for the unit name may vary. Language variants for the kilometre unit name include: chilometro (Italian), Kilometer (German),[Note 7] kilometer (Dutch), kilomètre (French), χιλιόμετρο (Greek), quilómetro/quilômetro (Portuguese), kilómetro (Spanish) and километр (Russian).[88][89]

Variations are also found with the spelling of unit names in countries using the same language, including differences in American English and British spelling. For example, meter and liter are used in the United States whereas metre and litre are used in other English-speaking countries. In addition, the official US spelling for the rarely used SI prefix for ten is deka. In American English the term metric ton is the normal usage whereas in other varieties of English tonne is common. Gram is also sometimes spelled gramme in English-speaking countries other than the United States, though this older usage is declining.[90]

Conversion and calculation incidents

The dual usage of or confusion between metric and non-metric units has resulted in a number of serious incidents. These include:

- Flying an overloaded American International Airways aircraft from Miami, Florida to Maiquetia, Venezuela on 26 May 1994. The degree of overloading was consistent with ground crew reading the kilogram markings on the cargo as pounds.[91]

- In 1999 the Institute for Safe Medication Practices reported that confusion between grains and grams led to a patient receiving phenobarbital 0.5 grams instead of 0.5 grains (0.03 grams) after the practitioner misread the prescription.[92]

- The Canadian "Gimli Glider" accident in 1983, when a Boeing 767 jet ran out of fuel in mid-flight because of two mistakes made when calculating the fuel supply of Air Canada's first aircraft to use metric measurements: mechanics miscalculated the amount of fuel required by the aircraft as a result of their unfamiliarity with metric units.[93]

- The root cause of the loss in 1999 of NASA's US$125 million Mars Climate Orbiter was a mismatch of units – the spacecraft engineers calculated the thrust forces required for velocity changes using US customary units (lbf·s) whereas the team who built the thrusters were expecting a value in metric units (N·s) as per the agreed specification.[94][95]

Conversion between SI and legacy units

During its evolution, the metric system has adopted many units of measure. The introduction of SI rationalised both the way in which units of measure were defined and also the list of units in use. These are now catalogued in the official SI Brochure.[20] The table below lists the units of measure in this catalogue and shows the conversion factors connecting them with the equivalent units that were in use on the eve of the adoption of SI.[96][97][98][99]

| Quantity | Dimension | SI unit and symbol | Legacy unit and symbol | Conversion factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | T | second (s) | second (s) | 1 |

| Length | L | metre (m) | centimetre (cm) ångström (Å) |

0.01 10−10 |

| Mass | M | kilogram (kg) | gram (g) | 0.001 |

| Electric current | I | ampere (A) | international ampere abampere or biot statampere |

1.000022 10.0 3.335641×10−10 |

| Temperature | Θ | kelvin (K) degree Celsius (°C) |

centigrade (°C) | [K] = [°C] + 273.15 1 |

| Luminous intensity | J | candela (cd) | international candle | 0.982 |

| Amount of substance | N | mole (mol) | No legacy unit | n/a |

| Area | L2 | square metre (m2) | are (are) | 100 |

| Acceleration | LT−2 | (m·s−2) | gal (gal) | 10−2 |

| Frequency | T−1 | hertz (Hz) | cycles per second | 1 |

| Energy | L2MT−2 | joule (J) | erg (erg) | 10−7 |

| Power | L2MT−3 | watt (W) | (erg/s) horsepower (HP) Pferdestärke (PS) |

10−7 745.7 735.5 |

| Force | LMT−2 | newton (N) | dyne (dyn) sthene (sn) kilopond (kp) |

10−5 103 9.80665 |

| Pressure | L−1MT−2 | pascal (Pa) | barye (Ba) pieze (pz) atmosphere (at) |

0.1 103 1.01325×105 |

| Electric charge | IT | coulomb (C) | abcoulomb statcoulomb or franklin |

10 3.335641×10−10 |

| Potential difference | L2MT−3I−1 | volt (V) | international volt abvolt statvolt |

1.00034 10−8 2.997925×102 |

| Capacitance | L−2M−1T4I2 | farad (F) | abfarad statfarad |

109 1.112650×10−12 |

| Inductance | L2MT−2I−2 | henry (H) | abhenry stathenry |

10−9 8.987552×1011 |

| Electric resistance | L2MT−3I−2 | ohm (Ω) | international ohm abohm statohm |

1.00049 10−9 8.987552×1011 |

| Electric conductance | L−2M−1T3I2 | siemens (S) | international mho (℧) abmho statmho |

0.99951 109 1.112650×10−12 |

| Magnetic flux | L2MT−2I−1 | weber (Wb) | maxwell (Mx) | 10−8 |

| Magnetic flux density | MT−2I−1 | tesla (T) | gauss (G) | 10−4 |

| Magnetic field strength | IL−1 | (A/m) | oersted (Oe) | 103⁄4π = 79.57747 |

| Dynamic viscosity | ML−1T−1 | (Pa·s) | poise (P) | 0.1 |

| Kinematic viscosity | L2T−1 | (m2·s−1) | stokes (St) | 10−4 |

| Luminous flux | J | lumen (lm) | stilb (sb) | 104 |

| Illuminance | JL−2 | lux (lx) | phot (ph) | 104 |

| [Radioactive] activity | T−1 | becquerel (Bq) | curie (Ci) | 3.70×1010 |

| Absorbed [radiation] dose | L2T−2 | gray (Gy) | roentgen (R) rad (rad) |

≈0.01[Note 8] 0.01 |

| Radiation dose equivalent | L2T−2 | sievert | roentgen equivalent man (rem) | 0.01 |

| Catalytic activity | NT−1 | katal (kat) | No legacy unit | n/a |

The SI Brochure also catalogues certain non-SI units that are widely used with the SI in matters of everyday life or units that are exactly defined values in terms of SI units and are used in particular circumstances to satisfy the needs of commercial, legal, or specialised scientific interests. These units include:[20]

| Quantity | Dimension | Unit and symbol | Equivalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass | M | tonne (t) | 1000 kg |

| Area | L2 | hectare (ha) | 0.01 km2 104 m2 |

| Volume | L3 | litre (L or l) | 0.001 m3 |

| Time | T | minute (min) hour (h) day (d) |

60 s 3600 s 86400 s |

| Pressure | L−1MT−2 | bar | 100 kPa |

| Plane angle | none | degree (°) minute (ʹ) second (″) |

( π⁄180) rad ( π⁄10800) rad ( π⁄648000) rad |

Future developments

After the metre was redefined in 1960, the kilogram was the only SI base unit that relied on a specific artefact. After the 1996–1998 recalibrations a clear divergence between the international and various national prototype kilograms was observed.[100]

At the 23rd CGPM (2007), the CIPM was mandated to investigate the use of natural constants as the basis for all units of measure rather than the artefacts that were then in use. At a meeting of the CCU held in Reading, United Kingdom in September 2010, a resolution[101] and draft changes to the SI brochure that were to be presented to the next meeting of the CIPM in October 2010 were agreed to in principle.[72] The CCU proposed to

- in addition to the speed of light, define four constants of nature—Planck's constant, an elementary charge, Boltzmann constant and Avogadro constant – to have exact values

- retire the international prototype kilogram

- revise the current definitions of the kilogram, ampere, kelvin and mole to make use of the above four constants of nature

- tighten the wording of the definitions of all the base units

The CIPM meeting of October 2010 found that "the conditions set by the General Conference at its 23rd meeting have not yet been fully met. For this reason the CIPM does not propose a revision of the SI at the present time".[102] The CIPM did however sponsor a resolution at the 24th CGPM in which the changes were agreed in principle and that were expected to be finalised at the 25th CGPM in 2014.[103]

See also

- Binary prefix, used in computer science

- Conversion of units

- History of measurement

- ISO/IEC 80000, style manual for measurements metric and non-metric, superseding ISO 31

- Metrication, the process of introducing the SI metric system as the worldwide standard for physical measurements

- Category:Metrication by country

- Metrology

- Lyn Nofziger, a prime opponent[104] of American metrication in the 1980s Reagan administration

- Units of measurement

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The following abbreviations are taken from the French rather than the English language

- ↑ Non-SI units for time and plane angle measurement, inherited from existing systems, are an exception to the decimal-multiplier rule

- ↑ Now called the degree Celsius

- ↑ An extremely learned or scholarly person – Oxford English Dictionary

- ↑ The CCU was set up in 1964 to replace the Commission for the System of Units—a commission established in 1954 to advise on the definition of SI.

- ↑ According to the Agence France-Presse report (2010) Liberia was metric, but Sierra Leone was not metric—a statement that conflicted with the CIA statement (2007).

- ↑ In German all nouns start with an upper-case letter

- ↑ Roentgen is a measure of ionisation (charge per mass), not of absorbed dose, so there is no well-defined conversion factor. However, a radiation field of gamma rays that produces 1 roentgen of ionisation in dry air would deposit 0.0096 gray in soft tissue, and between 0.01 and 0.04 grays in bone. Since this unit was often used in radiation detectors, a factor of 0.01 can be used to convert the detector reading in roentgens to the approximate absorbed dose in grays.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Alder, Ken (2002). The Measure of all Things—The Seven-Year-Odyssey that Transformed the World. London: Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11507-9.

- 1 2 29th Congress of the United States, Session 1 (13 May 1866). "H.R. 596, An Act to authorize the use of the metric system of weights and measures". Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- 1 2 Palaiseau, JFG (October 1816). Métrologie universelle, ancienne et moderne: ou rapport des poids et mesures des empires, royaumes, duchés et principautés des quatre parties du monde. Bordeaux. pp. 71–460. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ↑ "pint". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), pp. 121,122, ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-14

- 1 2 International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), p. 130, ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-14

- 1 2 O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (January 2004), "Simon Stevin", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- 1 2 Glaser, Anton (1981) [1971]. History of Binary and other Nondecimal Numeration (PDF) (Revised ed.). Tomash. pp. 71–72. ISBN 0-938228-00-5. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ de Morgan, Augustus (1854). Decimal Association (formed Jun 12, 1854)—Proceedings with an introduction by Professor de Morgan. London. p. 2. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ McGreevy, Thomas (1997). Cunningham, Peter, ed. The Basis of Measurement: Volume 2—Metrication and Current Practice. Chippenham: Picton Publishing. pp. 222–223. ISBN 0-948251-84-0.

- ↑ Brewster, D (1830). The Edinburgh Encyclopædia. p. 494.

- ↑ "What is a mise en pratique?". BIPM. 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ "OIML Mutual Acceptance Arrangement (MAA)". International Organization of Legal Metrology. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- 1 2 Nelson, Robert A (February 2000). "The International System of Units: Its History and Use in Science and Industry". Applied Technology Institute. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ↑ "Treaty of the Metre". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ "The BIPM and the evolution of the definition of the metre". BIPM. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- 1 2 International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), p. 109, ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-14

- ↑ "Leap Seconds". Washington, DC: Time Service Dept., U.S. Naval Observatory. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ Nelson, R.A; McCarthy, D.D; Malys, S; Levine, J; Guinot, B; Fliegel, H.F; Beard, R.L; Bartholomew, T.R (2001). "The leap second: its history and possible future" (PDF). Metrologia. 38 (6): 509–529. Bibcode:2001Metro..38..509N. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/38/6/6. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), pp. 111–120, ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-14

- ↑ "Caesium Atoms at Work". Time Service Department—U.S. Naval Observatory—Department of the Navy. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ↑ McKenzie, A.E.E (1961). Magnetism and Electricity. Cambridge University Press. p. 322.

- ↑ Wandmacher, Cornelius; Johnson, Arnold Ivan (1995). Metric Units in Engineering: Going SI (Revised ed.). American Society of Civil Engineers. pp. 225–226. ISBN 0-7844-0070-9.

- ↑ International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), pp. 113, 144, ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-14

- ↑ Mopberg, Roland, ed. (2008). "Linnaeus' thermometer". Uppsala Universitet. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), pp. 113, 114, 144, ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-14

- ↑ Page, Chester H; Vigoureux, Paul, eds. (20 May 1975). The International Bureau of Weights and Measures 1875–1975: NBS Special Publication 420. Washington, D.C.: National Bureau of Standards. pp. 238–244.

- ↑ Working Group 2 of the Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology (JCGM/WG 2). (2008), International vocabulary of metrology — Basic and general concepts and associated terms (VIM) (PDF) (3rd ed.), International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) on behalf of the Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology, 1.12, retrieved 12 April 2012

- ↑ Good, Michael. "Some Derivations of E = mc2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ↑ "Horsepower". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ MacLean, RW (20 December 1957). "A Central Program for Weights and Measures in Canada". Report of the 42nd National Conference on Weights and Measures 1957. National Bureau of Standards. p. 47. Miscellaneous publication 222. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ↑ J C Maxwell (1873). A treatise on electricity and magnetism. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 242–245. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 "La loi du 18 Germinal an 3 la mesure [républicaine] de superficie pour les terrains, égale à un carré de dix mètres de côté" [The law of 18 Germanial year 3 "The republican measures of land area equal to a square with sides of ten metres"] (in French). Le CIV (Centre d'Instruction de Vilgénis) – Forum des Anciens. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ↑ "Celebrating metrology: 51 years of SI units". Institute of Physics. 20 June 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ Wilkins, John (1668). "An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language". Royal Society: 190–194. (Reproduction – 34 MB), (Transcription – 126 kB)

- ↑ Dew, Nicholas (15–17 February 2008). The Hive and the Pendulum: Universal Metrology and Baroque Science (PDF). Baroque Science workshop. p. 5.

- ↑ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (January 2004), "Gabriel Mouton", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- ↑ Loidi, Juan Navarro; Saenz, Pilar Merino (6–9 September 2006). "The units of length in the Spanish treatises of military engineering" (PDF). The Global and the Local: The History of Science and the Cultural Integration of Europe. Proceedings of the 2nd ICESHS. Cracow, Poland: The Press of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ Anticole, Matt. "Why the metric system matters". Ted-Ed. TED. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson (4 July 1790). "Plan for Establishing Uniformity in the Coinage, Weights, and Measures of the United States". Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ↑ Thierry Thomasset. "Le stère" (PDF). Tout sur les unités de mesure [All the units of measure] (in French). Université de Technologie de Compiègne. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- 1 2 National Industrial Conference Board (1921). The metric versus the English system of weights and measures. The Century Co. pp. 10–11. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ Denis Février. "Un historique du mètre" (in French). Ministère de l'Economie, des Finances et de l'Industrie. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- 1 2 "Amtliche Maßeinheiten in Europa 1842" [Official units of measure in Europe 1842] (in German). Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ↑ Jacob de Gelder (1824). Allereerste Gronden der Cijferkunst [Introduction to Numeracy] (in Dutch). 's Gravenhage and Amsterdam: de Gebroeders van Cleef. pp. 163–176. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ↑ Ferdinand Malaisé (1842). Theoretisch-practischer Unterricht im Rechnen [Theoretical and practical instruction in arithmetic] (in German). München. pp. 307–322. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ↑ "Fundstück des Monats November 2006" [Exhibit of the month – November 2006] (in German). Bundesministerium der Finanzen [German] Federal Ministry of Finance. 4 June 2009. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ Cochrane, Rexmond Canning (1966). Measures for Progress: A History of the National Bureau of Standards. National Bureau of Standards. p. 530. LCCN 65-62472. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ↑ Maria Teresa Borgato (6–9 September 2006). "The first applications of the metric system in Italy" (PDF). The Global and the Local: The History of Science and the Cultural Integration of Europe. Proceedings of the 2nd ICESHS. Cracow, Poland: The Press of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ Secretary, the Metric committee (1873). "Report on the best means of providing a Uniformity of Weights and Measures, with reference to the Interests of Science". Report of the forty second meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science held at Brighton, August 1872. British Association for the Advancement of Science: 25–28. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ↑ "Metric Measure in U.S. Asked." Popular Science Monthly, January 1928, p. 53.

- ↑ Maxwell, J C (1873). A treatise on electricity and magnetism. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 242–245. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ↑ Professor Everett; et al., eds. (1874). "First Report of the Committee for the Selection and Nomenclature of Dynamical and Electrical Units". Report on the Forty-third Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science held at Bradford in September 1873. British Association for the Advancement of Science: 222–225. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ↑ "Convention du mètre" (PDF) (in French). Bureau international des poids et mesures (BIPM). Retrieved 22 March 20111875 text plus 1907 and 1921 amendments

- ↑ "The metre convention". Bureau international des poids et mesures (BIPM). Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- 1 2 "System of Measurement Units". IEEE Global History Network. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ↑ Linton, Otha W. "History". International Society of Radiology. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ "Résolution 10 de la 8e réunion de la CGPM (1933)—Substitution des unités électriques absolues aux unités dites " internationales "" [Resolution 10 of the 8th meeting of the CGPM (1933)—Substitution of the so-called "International" electrical units by absolute electrical units] (in French). Bureau International des Poids et Meseures. 1935. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ↑ "Criteria for membership of the CCU". International Bureau of Weights and Measures. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ↑ Thomson, William; Joule, James Prescott; Maxwell, James Clerk; Jenkin, Flemming (1873). "First Report – Cambridge 3 October 1862". In Jenkin, Flemming. Reports on the Committee on Standards of Electrical Resistance – Appointed by the British Association for the Advancement of Science. London. pp. 1–3. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ↑ "Historical context of the SI—Unit of electric current (ampere)". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units and Uncertainty. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ↑ "In the beginning... Giovanni Giorgi". International Electrotechnical Commission. 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ↑ "Notions de physique – Systèmes d'unités" [Symbols used in physics – units of measure] (in French). Hydrelect.info. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ↑ Michon, Gérard P (9 September 2000). "Final Answers". Numericana.com. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ "Resolution of the 3rd meeting of the CGPM (1901)". General Conference on Weights and Measures. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ Resolution 6—Proposal for establishing a practical system of units of measurement. 9th Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures (CGPM). 12–21 October 1948. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ↑ Resolution 7—Writing and printing of unit symbols and of numbers. 9th Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures (CGPM). 12–21 October 1948. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ↑ Resolution 6 – Practical system of units. 10th Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures (CGPM). 5–14 October 1954. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ↑ Resolution 12—Système International d'Unités. 11th Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures (CGPM). 11–20 October 1960. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ↑ "Practical realization of the definitions of some important units". SI brochure, Appendix 2. BIPM. 9 September 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-14

- 1 2 Ian Mills (29 September 2010). "Draft Chapter 2 for SI Brochure, following redefinitions of the base units" (PDF). CCU. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ↑ International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), pp. 124–129, ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-14

- ↑ "The World Factbook". Washington: Central Intelligence Agency. 2007. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

At this time, only three countries – Burma, Liberia, and the US – have not adopted the International System of Units (SI, or metric system) as their official system of weights and measures.

- ↑ "The United States and the metric system" (PDF). NIST. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

The United States is now the only industrialized country in the world that does not use the metric system as its predominant system of measurement.

- ↑ Kuhn, Markus (1 December 2009). "Metric System FAQ". misc.metric-system Newsgroup. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ↑ "S.Leone goes metric after 49 years". Agence France-Presse. 11 June 2010. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ↑ Ko Ko Gyi (18–24 July 2011). "Ditch the viss, govt urges traders". The Myanmar Times. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ↑ Jasper, Kelly (4 April 2013). "Metric system use on the rise in the U.S.". The Augusta Chronicle. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ↑ Buchholz, Susan; Henke, Grace (2009). Henke's Med-Math: Dosage Calculation, Preparation & Administration (Sixth ed.). Wolters Kluwer and Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-7817-7628-8. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- 1 2 Kelly, Jon (21 December 2011). "Will British people ever think in metric?". BBC.

...but today the British remain unique in Europe by holding onto imperial weights and measures. Call it a proud expression of national identity or a stubborn refusal to engage with the neighbours, the persistent British preference for imperial over metric is particularly noteworthy...

- ↑ "Why Won’t America Go Metric?". Time. Retrieved 6 October 2015

- ↑ "Why the US hasn't fully adopted the metric system". CNBC. Retrieved 6 October 2015

- ↑ "Metric usage and metrication in other countries". U.S. Metric Association. 22 July 2009. Archived from the original on 21 February 1999. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ↑ "Department for Transport statement on metric road signs" (online). BWMA. 12 July 2002. Retrieved 24 August 2009.

- ↑ "EU gives up on 'metric Britain". BBC News. 11 September 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ "HK Weights and Measures Ordinance". Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ↑ "Online Translation—Offering hundreds of dictionaries and translation in more than 800 language pairs". Babylon. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ↑ Working Group 2 of the Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology (JCGM/WG 2). (2008), International vocabulary of metrology — Basic and general concepts and associated terms (VIM) (PDF) (3rd ed.), International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) on behalf of the Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology, p. 9, retrieved 5 March 2011

- ↑ "Weights and Measures Act 1985 (c. 72)". The UK Statute Law Database. Office of Public Sector Information. Archived from the original on 12 September 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

§ 92.

- ↑ "NTSB Order No. EA-4510" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Transportation Safety Board. 1996. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ↑ "ISMP Medication Safety Alert". Institute for Safe Medication Practices. 14 July 1999. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ↑ Williams, Merran (July–August 2003). "The 156-tonne Gimli Glider" (PDF). Flight Safety Australia: 22–27. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ↑ "NASA's metric confusion caused Mars orbiter loss". CNN. 30 September 1999. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- ↑ "Mars Climate Orbiter; Mishap Investigation Board; Phase I Report" (PDF). NASA. 10 November 1999. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ↑ "Index to Units & Systems of Units". sizes.com. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ↑ "Factors for Units Listed Alphabetically". NIST Guide to the SI. 2 July 2009. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. pp. 110–116. Electronic version..

- ↑ Fenna, Donald (2002). Oxford Dictionary of Weights, Measures and Units. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860522-6.

- ↑ Peter Mohr (6 December 2010). "Recent progress in fundamental constants and the International System of Units" (PDF). Third Workshop on Precision Physics and Fundamental Physical Constants. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ↑ Ian Mills (29 September 2010). "On the possible future revision of the International System of Units, the SI" (PDF). CCU. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ↑ "Towards the "new SI"". International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM). Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- ↑ Resolution 1—On the possible future revision of the International System of Units, the SI (PDF). 24th meeting of the General Conference on Weights and Measures. Sèvres, France. 17–21 October 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ↑ Mankiewicz, Frank (March 29, 2006). "Nofziger: A Friend With Whom It Was a Pleasure to Disagree". WashingtonPost.com. Washington Post. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

External links

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Using the Metric System |

- CBC Radio Archives For Good Measure: Canada Converts to Metric

- U.S. Metric Association Metrication in other countries