Dysgeusia

| Dysgeusia | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation |

|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, Neurology, Dentistry, Gastroenterology, Endocrinology |

| ICD-10 | R43.2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 781.1 |

| DiseasesDB | 27369 |

| MedlinePlus | 003050 |

| eMedicine | ent/333 |

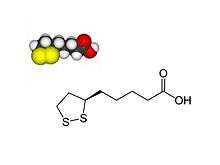

Dysgeusia, also known as parageusia, is a distortion of the sense of taste. Dysgeusia is also often associated with ageusia, which is the complete lack of taste, and hypogeusia, which is a decrease in taste sensitivity.[1] An alteration in taste or smell may be a secondary process in various disease states, or it may be the primary symptom. The distortion in the sense of taste is the only symptom, and diagnosis is usually complicated since the sense of taste is tied together with other sensory systems. Common causes of dysgeusia include chemotherapy, asthma treatment with albuterol, and zinc deficiency. Different drugs could also be responsible for altering taste and resulting in dysgeusia. Due to the variety of causes of dysgeusia, there are many possible treatments that are effective in alleviating or terminating the symptoms of dysgeusia. These include artificial saliva, pilocarpine, zinc supplementation, alterations in drug therapy, and alpha lipoic acid.

Symptoms

The alterations in the sense of taste, usually a metallic taste, and sometimes smell are the only symptoms.[2] The duration of the symptoms of dysgeusia depends on the cause. If the alteration in the sense of taste is due to gum disease, dental plaque, a temporary medication, or a short-term condition such as a cold, the dysgeusia should disappear once the cause is removed. In some cases, if lesions are present in the taste pathway and nerves have been damaged, the dysgeusia may be permanent.

Causes

Chemotherapy

A major cause of dysgeusia is chemotherapy for cancer. Chemotherapy often induces damage to the oral cavity, resulting in oral mucositis, oral infection, and salivary gland dysfunction. Oral mucositis consists of inflammation of the mouth, along with sores and ulcers in the tissues.[3] Healthy individuals normally have a diverse range of microbial organisms residing in their oral cavities; however, chemotherapy can permit these typically non-pathogenic agents to cause serious infection, which may result in a decrease in saliva. In addition, patients who undergo radiation therapy also lose salivary tissues.[4] Saliva is an important component of the taste mechanism. Saliva both interacts with and protects the taste receptors in the mouth.[5] Saliva mediates sour and sweet tastes through bicarbonate ions and glutamate, respectively.[6] The salt taste is induced when sodium chloride levels surpass the concentration in the saliva.[6] It has been reported that 50% of chemotherapy patients have suffered from either dysgeusia or another form of taste impairment.[3] Examples of chemotherapy treatments that can lead to dysgeusia are cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and etoposide.[3] The exact mechanism of chemotherapy-induced dysgeusia is unknown.[3]

Taste buds

Distortions in the taste buds may give rise to dysgeusia. In a study conducted by Masahide Yasuda and Hitoshi Tomita from Nihon University of Japan, it has been observed that patients suffering from this taste disorder have fewer microvilli than normal. In addition, the nucleus and cytoplasm of the taste bud cells have been reduced. Based on their findings, dygeusia results from loss of microvilli and the reduction of Type III intracellular vesicles, all of which could potentially interfere with the gustatory pathway.[7]

Zinc deficiency

Another primary cause of dysgeusia is zinc deficiency. While the exact role of zinc in dysgeusia is unknown, it has been cited that zinc is partly responsible for the repair and production of taste buds. Zinc somehow directly or indirectly interacts with carbonic anhydrase VI, influencing the concentration of gustin, which is linked to the production of taste buds.[8] It has also been reported that patients treated with zinc experience an elevation in calcium concentration in the saliva.[8] In order to work properly, taste buds rely on calcium receptors.[9] Zinc “is an important cofactor for alkaline phosphatase, the most abundant enzyme in taste bud membranes; it is also a component of a parotid salivary protein important to the development and maintenance of normal taste buds.”[9]

Drugs

There are also a wide variety of drugs that can trigger dysgeusia, including zopiclone,[10] H1-antihistamines, such as azelastine and emedastine.[11] Approximately 250 drugs affect taste.[12] The sodium channels linked to taste receptors can be inhibited by amiloride, and the creation of new taste buds and saliva can be impeded by antiproliferative drugs.[12] Saliva can have traces of the drug, giving rise to a metallic flavor in the mouth; examples include lithium carbonate and tetracyclines.[12] Drugs containing sulfhydryl groups, including penicillamine and captopril, may react with zinc and cause deficiency.[9] Metronidazole and chlorhexidine have been found to interact with metal ions that associate with the cell membrane.[13] Drugs that prevent the production of angiotensin II by inhibiting angiotensin converting enzyme, eprosartan for example, have been linked to dysgeusia.[14] There are few case reports claiming calcium channel blockers like Amlodipine also cause dysguesia by blocking calcium sensitive taste buds.[15]

Miscellaneous causes

Xerostomia, also known as dry mouth syndrome, can precipitate dysgeusia because normal salivary flow and concentration are necessary for taste. Injury to the glossopharyngeal nerve can result in dysgeusia. In addition, damage done to the pons, thalamus, and midbrain, all of which compose the gustatory pathway, can be potential factors.[16] In a case study, 22% of patients who were experiencing a bladder obstruction were also suffering from dysgeusia. Dysgeusia was eliminated in 100% of these patients once the obstruction was removed.[16] Although it is uncertain what the relationship between bladder relief and dysgeusia entails, it has been observed that the areas responsible for urinary system and taste in the pons and cerebral cortex in the brain are close in proximity.[16]

Many of the causes for dysgeusia occur due to unknown reasons. A wide range of miscellaneous factors may contribute to this taste disorder, such as gastric reflux, lead poisoning, and diabetes mellitus.[17] A minority of pine nuts can apparently cause taste disturbances, for reasons which are not entirely proven. Certain pesticides can have damaging effects on the taste buds and nerves in the mouth. These pesticides include organochloride compounds and carbamate pesticides. Damage to the peripheral nerves, along with injury to the chorda tympani branch of the facial nerve, also cause dysgeusia.[17] A surgical risk for laryngoscopy and tonsillectomy include dysgeusia.[17] Patients who suffer from the burning mouth syndrome, most likely menopausal women, are often suffering from dysgeusia as well.[18]

Normal function

The sense of taste is based on the detection of chemicals by specialized taste cells in the mouth. The mouth, throat, larynx, and esophagus all have taste buds, which are replaced every ten days. Each taste bud contains receptor cells.[17] Afferent nerves make contact with the receptor cells at the base of the taste bud.[19] A single taste bud is innervated by several afferent nerves, while a single efferent fiber innervates several taste buds.[20] Fungiform papillae are present on the anterior portion of the tongue while circumvallate papillae and foliate papillae are found on the posterior portion of the tongue. The salivary glands are responsible for keeping the taste buds moist with saliva.[21]

A single taste bud is composed of four different types of cells, and each taste bud has at least 30 to 80 cells. Type I cells are thinly shaped, usually in the periphery of other cells. They also contain high amounts of chromatin. Type II cells have prominent nuclei and nucleoli with much less chromatin than Type I cells. Type III cells have multiple mitochondria and large vesicles. Type I, II, and III cells also contain synapses. Type IV cells are normally rooted at the posterior end of the taste bud. Every cell in the taste bud forms microvilli at the ends.[7]

In humans, the sense of taste is conveyed via three of the twelve cranial nerves. The chorda tympani is responsible for taste sensations from the anterior two thirds of the tongue, the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX) is responsible for taste sensations from the posterior one third of the tongue while a branch of the vagus nerve (X) carries some taste sensations from the back of the oral cavity.

Diagnosis

In general, gustatory disorders are challenging to diagnose and evaluate. Because gustatory functions are tied to the sense of smell, the somatosensory system, and the perception of pain (such as in tasting spicy foods), it is difficult to examine sensations mediated through an individual system.[22] In addition, gustatory dysfunction is rare when compared to olfactory disorders.[23]

Diagnosis of dysgeusia begins with the patient being questioned about salivation, swallowing, chewing, oral pain, previous ear infections (possibly indicated by hearing or balance problems), oral hygiene, and stomach problems.[24] The initial history assessment also considers the possibility of accompanying diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, or cancer.[24] A clinical examination is conducted and includes an inspection of the tongue and the oral cavity. Furthermore, the ear canal is inspected, as lesions of the chorda tympani have a predilection for this site.[24]

Gustatory testing

In order to further classify the extent of dysgeusia and clinically measure the sense of taste, gustatory testing may be performed. Gustatory testing is performed either as a whole-mouth procedure or as a regional test. In both techniques, natural or electrical stimuli can be used. In regional testing, 20 to 50 µL of liquid stimulus is presented to the anterior and posterior tongue using a pipette, soaked filter-paper disks, or cotton swabs.[23] In whole mouth testing, small quantities (2-10 mL) of solution are administered, and the patient is asked to swish the solution around in the mouth.[23]

Threshold tests for sucrose (sweet), citric acid (sour), sodium chloride (salty), and quinine or caffeine (bitter) are frequently performed with natural stimuli. One of the most frequently used techniques is the "three-drop test."[25] In this test, three drops of liquid are presented to the subject. One of the drops is of the taste stimulus, and the other two drops are pure water.[25] Threshold is defined as the concentration at which the patient identifies the taste correctly three times in a row.[25]

Suprathreshold tests, which provide intensities of taste stimuli above threshold levels, are used to assess the patient's ability to differentiate between different intensities of taste and to estimate the magnitude of suprathreshold loss of taste. From these tests, ratings of pleasantness can be obtained using either the direct scaling or magnitude matching method and may be of value in the diagnosis of dysgeusia. Direct scaling tests show the ability to discriminate among different intensities of stimuli and whether a stimulus of one quality (sweet) is stronger or weaker than a stimulus of another quality (sour).[26] Direct scaling cannot be used to determine if a taste stimulus is being perceived at abnormal levels. In this case, magnitude matching is used, in which a patient is asked to rate the intensities of taste stimuli and stimuli of another sensory system, such as the loudness of a tone, on a similar scale.[26] For example, the Connecticut Chemosensory Clinical Research Center asks patients to rate the intensities of NaCl, sucrose, citric acid and quinine-HCl stimuli, and the loudness of 1000 Hz tones.[26] Assuming normal hearing, the results of this cross-sensory test show the relative strength of the sense of taste in relation to the loudness of the auditory stimulus. Although many of the tests are based on ratings using the direct scaling method, some tests do use the magnitude-matching procedure.

Other tests include identification or discrimination of common taste substances. Topical anesthesia of the tongue has been reported to be of use in the diagnosis of dysgeusia as well, since it has been shown to relieve the symptoms of dysgeusia temporarily.[23] In addition to techniques based on the administration of chemicals to the tongue, electrogustometry is frequently used. It is based on the induction of gustatory sensations by means of an anodal electrical direct current. Patients usually report sour or metallic sensations similar to those associated with touching both poles of a live battery to the tongue.[27] Although electrogustometry is widely used, there seems to be a poor correlation between electrically and chemically induced sensations.[28]

Diagnostic tools

Certain diagnostic tools can also be used to help determine the extent of dysgeusia. Electrophysiological tests and simple reflex tests may be applied to identify abnormalities in the nerve-to-brainstem pathways. For example, the blink reflex may be used to evaluate the integrity of the trigeminal nerve–pontine brainstem–facial nerve pathway, which may play a role in gustatory function.[29]

Structural imaging is routinely used to investigate lesions in the taste pathway. Magnetic resonance imaging allows direct visualization of the cranial nerves.[30] Furthermore, it provides significant information about the type and cause of a lesion.[30] Analysis of mucosal blood flow in the oral cavity in combination with the assessment of autonomous cardiovascular factors appears to be useful in the diagnosis of autonomic nervous system disorders in burning mouth syndrome and in patients with inborn disorders, both of which are associated with gustatory dysfunction.[31] Cell cultures may also be used when fungal or bacterial infections are suspected.

In addition, the analysis of saliva should be performed, as it constitutes the environment of taste receptors, including transport of tastes to the receptor and protection of the taste receptor.[32] Typical clinical investigations involve sialometry and sialochemistry.[32] Studies have shown that electron micrographs of taste receptors obtained from saliva samples indicate pathological changes in the taste buds of patients with dysgeusia and other gustatory disorders.[33]

Treatments

Artificial saliva and pilocarpine

Because medications have been linked to approximately 22% to 28% of all cases of dysgeusia, researching a treatment for this particular cause has been important.[34] Xerostomia, or a decrease in saliva flow, can be a side effect of many drugs, which, in turn, can lead to the development of taste disturbances such as dysgeusia.[34] Patients can lessen the effects of xerostomia with breath mints, sugarless gum, or lozenges, or physicians can increase saliva flow with artificial saliva or oral pilocarpine.[34] Artificial saliva mimics the characteristics of natural saliva by lubricating and protecting the mouth but does not provide any digestive or enzymatic benefits.[35] Pilocarpine is a cholinergic drug meaning it has the same effects as the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Acetylcholine has the function of stimulating the salivary glands to actively produce saliva.[36] The increase in saliva flow is effective in improving the movement of tastants to the taste buds.[34]

Zinc deficiency

Zinc supplementation

Approximately one half of drug-related taste distortions are caused by a zinc deficiency.[34] Many medications are known to chelate, or bind, zinc, preventing the element from functioning properly.[34] Due to the causal relationship of insufficient zinc levels to taste disorders, research has been conducted to test the efficacy of zinc supplementation as a possible treatment for dysgeusia. In a randomized clinical trial, fifty patients suffering from idiopathic dysgeusia were given either zinc or a lactose placebo.[8] The patients prescribed the zinc reported experiencing improved taste function and less severe symptoms compared to the control group, suggesting that zinc may be a beneficial treatment.[8] The efficacy of zinc, however, has been ambiguous in the past. In a second study, 94% of patients who were provided with zinc supplementation did not experience any improvement in their condition.[34] This ambiguity is most likely due to small sample sizes and the wide range of causes of dysgeusia.[8] A recommended daily oral dose of 25–100 mg appears to be an effective treatment for taste dysfunction provided that there are low levels of zinc in the blood serum.[37] There is not a sufficient amount of evidence to determine whether or not zinc supplementation is able to treat dysgeusia when low zinc concentrations are not detected in the blood.[37]

Zinc infusion in chemotherapy

It has been reported that approximately 68% of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy experience disturbances in sensory perception such as dysgeusia.[38] In a pilot study involving twelve lung cancer patients, chemotherapy drugs were infused with zinc in order to test its potential as a treatment.[39] The results indicated that, after two weeks, no taste disturbances were reported by the patients who received the zinc-supplemented treatment while most of the patients in the control group who did not receive the zinc reported taste alterations.[39] A multi-institutional study involving a larger sample size of 169 patients, however, indicated that zinc-infused chemotherapy did not have an effect on the development of taste disorders in cancer patients.[38] An excess amount of zinc in the body can have negative effects on the immune system, and physicians must use caution when administering zinc to immunocompromised cancer patients.[38] Because taste disorders can have detrimental effects on a patient's quality of life, more research needs to be conducted concerning possible treatments such as zinc supplementation.[40]

Altering drug therapy

The effects of drug-related dysgeusia can often be reversed by stopping the patient's regimen of the taste altering medication.[41] In one case, a forty-eight-year-old woman who was suffering from hypertension was being treated with valsartan.[42] Due to this drug's inability to treat her condition, she began taking a regimen of eprosartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist.[42] Within three weeks, she began experiencing a metallic taste and a burning sensation in her mouth that ceased when she stopped taking the medication.[42] When she began taking eprosartan on a second occasion, her dysgeusia returned.[42] In a second case, a fifty-nine-year-old man was prescribed amlodipine in order to treat his hypertension.[43] After eight years of taking the drug, he developed a loss of taste sensation and numbness in his tongue.[43] When he ran out of his medication, he decided not to obtain a refill and stopped taking amlodipine.[43] Following this self-removal, he reported experiencing a return of his taste sensation.[43] Once he refilled his prescription and began taking amlodipine a second time, his taste disturbance reoccurred.[43] These two cases suggest that there is an association between these drugs and taste disorders. This link is supported by the "de-challenge" and "re-challenge" that took place in both instances.[43] It appears that drug-induced dysgeusia can be alleviated by reducing the drug's dose or by substituting a second drug from the same class.[34]

Alpha lipoic acid

Alpha lipoic acid (ALA) is an antioxidant that is made naturally by human cells.[44] It can also be administered in capsules or can be found in foods such as red meat, organ meats, and yeast.[44] Like other antioxidants, it functions by ridding the body of harmful free radicals that can cause damage to tissues and organs.[44] It has an important role in the Krebs cycle as a coenzyme leading to the production of antioxidants, intracellular glutathione, and nerve-growth factors.[45] Animal research has also uncovered the ability of ALA to improve nerve conduction velocity.[45] Because flavors are perceived by differences in electric potential through specific nerves innervating the tongue, idiopathic dysgeusia may be a form of a neuropathy.[45] ALA has proven to be an effective treatment for burning mouth syndrome spurring studies in its potential to treat dysgeusia.[45] In a study of forty-four patients diagnosed with the disorder, one half was treated with the drug for two months while the other half, the control group, was given a placebo for two months followed by a two-month treatment of ALA.[45] The results reported show that 91% of the group initially treated with ALA reported an improvement in their condition compared to only 36% of the control group.[45] After the control group was treated with ALA, 72% reported an improvement.[45] This study suggests that ALA may be a potential treatment for patients and supports that full double blind randomized studies should be performed.[45]

Managing dysgeusia

In addition to the aforementioned treatments, there are also many management approaches that can alleviate the symptoms of dysgeusia. These include using non-metallic silverware, avoiding metallic or bitter tasting foods, increasing the consumption of foods high in protein, flavoring foods with spices and seasonings, serving foods cold in order to reduce any unpleasant taste or odor, frequently brushing one's teeth and utilizing mouthwash, or using sialogogues such as chewing sugar-free gum or sour-tasting drops that stimulate the productivity of saliva.[38] When taste is impeded, the food experience can be improved through means other than taste, such as texture, aroma, temperature, and color.[41]

Psychological impacts

People who suffer from dysgeusia are also forced to manage the impact that the disorder has on their quality of life. An altered taste has effects on food choice and intake and can lead to weight loss, malnutrition, impaired immunity, and a decline in health.[41] Patients diagnosed with dysgeusia must use caution when adding sugar and salt to food and must be sure not to overcompensate for their lack of taste with excess amounts.[41] Since the elderly are often on multiple medications, they are at risk for taste disturbances increasing the chances of developing depression, loss of appetite, and extreme weight loss.[46] This is cause for an evaluation and management of their dysgeusia. In patients undergoing chemotherapy, taste distortions can often be severe and make compliance with cancer treatment difficult.[39] Other problems that may arise include anorexia and behavioral changes that can be misinterpreted as psychiatric delusions regarding food.[47] Symptoms including paranoia, amnesia, cerebellar malfunction, and lethargy can also manifest when undergoing histidine treatment.[47] This makes it critical that these patients' dysgeusia is either treated or managed in order to improve their quality of life.

Future research

Every year, more than 200,000 individuals see their physicians concerning chemosensory problems, and many more taste disturbances are never reported.[48] Due to the large number of persons affected by taste disorders, basic and clinical research are receiving support at different institutions and chemosensory research centers across the country.[48] These taste and smell clinics are focusing their research on better understanding the mechanisms involved in gustatory function and taste disorders such as dysgeusia. For example, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders is looking into the mechanisms underlying the key receptors on taste cells and applying this knowledge to the future of medications and artificial food products.[48] Meanwhile, the Taste and Smell Clinic at the University of Connecticut Health Center is integrating behavioral, neurophysiological, and genetic studies involving stimulus concentrations and intensities in order to better understand taste function.[49] The purpose of these studies is to unearth the biological mechanisms underlying taste and to use this data to eliminate taste disorders in order to improve the lives of taste disorder sufferers.

See also

References

- ↑ Samuel K. Feske and Martin A. Samuels, Office Practice of Neurology 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier Science, 2003) 114.

- ↑ Hoffman, HJ; Ishii, EK; MacTurk, RH (30 November 1998). "Age-related changes in the prevalence of smell/taste problems among the United States adult population. Results of the 1994 disability supplement to the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 855: 716–22. PMID 9929676. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10650.x.

- 1 2 3 4 Raber-Durlacher, Judith E.; Barasch, Andrei; Peterson, Douglas E.; Lalla, Rajesh V.; Schubert, Mark M.; Fibbe, Willem E. (July 2004). "Oral Complications and Management Considerations in Patients Treated with High-Dose Chemotherapy". Supportive Cancer Therapy. 1 (4): 219–229. PMID 18628146. doi:10.3816/SCT.2004.n.014.

- ↑ Wiseman, Michael (June 2006). "The treatment of oral problems in the palliative patient.". Journal (Canadian Dental Association). 72 (5): 453–8. PMID 16772071.

- ↑ R. Matsuo, "Role of saliva in the maintenance of taste sensitivity," Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med., 2000: 11.

- 1 2 A. L. Speilman, "Interaction of Saliva and Taste," J DENT RES, 1990: 69.

- 1 2 Yasuda, Masahide; Tomita, Hitoshi (8 July 2009). "Electron Microscopic Observations of Glossal Circumvallate Papillae in Dysgeusic Patients". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 122 (4): 122–128. doi:10.1080/00016480260046508.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Heckmann, SM; Hujoel, P; Habiger, S; Friess, W; Wichmann, M; Heckmann, JG; Hummel, T (1 January 2005). "Zinc gluconate in the treatment of dysgeusia--a randomized clinical trial.". Journal of dental research. 84 (1): 35–8. PMID 15615872. doi:10.1177/154405910508400105.

- 1 2 3 Joseph M. Bicknell, MD and Robert V. Wiggins, MD, “Taste Disorder From Zinc Deficiency After Tonsillectomy,” The Western Journal of Medicine Oct.1988: 458.

- ↑ Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Limited. "Product Information IMOVANE (zopiclone) Tablets" (PDF). ADVERSE EFFECTS. p. 6. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ Simons, F. Estelle R. (18 November 2004). "Advances in H1-Antihistamines". New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (21): 2203–2217. PMID 15548781. doi:10.1056/NEJMra033121.

- 1 2 3 Samuel K. Feske and Martin A. Samuels, Office Practice of Neurology 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier Science, 2003) 119.

- ↑ Ciancio, Sebastian G. (October 2004). "Medications' impact on oral health.". Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 135 (10): 1440–8; quiz 1468–9. PMID 15551986.

- ↑ Castells, X. (30 November 2002). "Drug points: Dysgeusia and burning mouth syndrome by eprosartan". BMJ. 325 (7375): 1277–1277. PMID 12458247. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1277.

- ↑ Pugazhenthan Thangaraju, Harmanjith Singh, Prince Kumar and Balasubramani Hariharan,"Is Dysguesia going to be a rare or a common side-effect of Amlodipine?,"Ann Med Health Sci Res,Mar-Apr 2014: PMC 4083725.

- 1 2 3 R. K. Mal and M. A. Birchall, “Dysgeusia related to urinary obstruction from benign prostatic disease: a case control and qualitative study,” European Archives of Oto-Rhino Laryngology 24 Aug. 2005:178.

- 1 2 3 4 Norman M. Mann, MD, “Management of Smell and Taste Problems,” Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine Apr. 2002: 334.

- ↑ Giuseppe Lauria, Alessandra Majorana, Monica borgna, Raffaella Lombardi, Paola Penza, Alessandro padovani, and Pierluigi Sapelli, “Trigeminal small-fiber sensory neuropathy causes burning mouth syndrome,” Pain 11 Mar. 2005: 332, 336.

- ↑ Brand, Joseph G (October 2000). "Within reach of an end to unnecessary bitterness?". The Lancet. 356 (9239): 1371–1372. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02836-1.

- ↑ Beidler, L. M. (1 November 1965). "Renewal of cells within taste buds". The Journal of Cell Biology. 27 (2): 263–272. doi:10.1083/jcb.27.2.263.

- ↑ Bromley, SM (15 January 2000). "Smell and taste disorders: a primary care approach.". American family physician. 61 (2): 427–36, 438. PMID 10670508.

- ↑ Deems, DA; Doty, RL; Settle, RG; Moore-Gillon, V; Shaman, P; Mester, AF; Kimmelman, CP; Brightman, VJ; Snow JB, Jr (1 May 1991). "Smell and taste disorders, a study of 750 patients from the University of Pennsylvania Smell and Taste Center.". Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 117 (5): 519–28. PMID 2021470. doi:10.1001/archotol.1991.01870170065015.

- 1 2 3 4 Hummel T, Knecht M. Smell and taste disorders. In: Calhoun KH, ed. Expert Guide to Otolaryngology. Philadelphia, Pa: American College of Physicians; 2001:650-664.

- 1 2 3 Epstein, Franklin H.; Schiffman, Susan S. (26 May 1983). "Taste and Smell in Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 308 (21): 1275–1279. PMID 6341841. doi:10.1056/NEJM198305263082107.

- 1 2 3 Ahne, Gabi; Erras, Angelo; Hummel, Thomas; Kobal, Gerd (August 2000). "Assessment of Gustatory Function by Means of Tasting Tablets". The Laryngoscope. 110 (8): 1396–1401. PMID 10942148. doi:10.1097/00005537-200008000-00033.

- 1 2 3 Seiden, Allen M., “Taste and Smell Disorders (Rhinology & Sinusology),” Thieme Publishing Group Aug. 2000: 153.

- ↑ Stillman, JA; Morton, RP; Goldsmith, D (April 2000). "Automated electrogustometry: a new paradigm for the estimation of taste detection thresholds.". Clinical otolaryngology and allied sciences. 25 (2): 120–5. PMID 10816215. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2273.2000.00328.x.

- ↑ Murphy, Claire; Quiñonez, Carlo; Nordin, Steven (1995). "Reliability and Validity of Electrogustometry and its Application to Young and Elderly Persons". Chemical Senses. 20 (5): 499–503. PMID 8564424. doi:10.1093/chemse/20.5.499.

- ↑ Jääskeläinen, Satu K; Forssell, Heli; Tenovuo, Olli (December 1997). "Abnormalities of the blink reflex in burning mouth syndrome". Pain. 73 (3): 455–460. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00140-1.

- 1 2 Lell, M; Schmid, A; Stemper, B; Maihöfner, C; Heckmann, JG; Tomandl, BF (18 December 2002). "Simultaneous involvement of third and sixth cranial nerve in a patient with Lyme disease.". Neuroradiology. 45 (2): 85–7. PMID 12592489. doi:10.1007/s00234-002-0904-x.

- ↑ Heckmann, Josef G.; Hilz, Max J.; Hummel, Thomas; Popp, Michael; Marthol, Harald; Neundörfer, Bernhard; Heckmann, Siegfried M. (October 2000). "Oral mucosal blood flow following dry ice stimulation in humans". Clinical Autonomic Research. 10 (5): 317–321. PMID 11198489. doi:10.1007/BF02281116.

- 1 2 Matsuo, R (April 2000). "Role of Saliva in the Maintenance of Taste Sensitivity". Critical Reviews in Oral Biology & Medicine. 11 (2): 216–229. PMID 12002816. doi:10.1177/10454411000110020501.

- ↑ Henkin, Robert I. (26 July 1971). "Idiopathic Hypogeusia With Dysgeusia, Hyposmia, and Dysosmia". JAMA. 217 (4): 434. PMID 5109029. doi:10.1001/jama.1971.03190040028006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Giudice, M. (1 March 2006). "Taste Disturbances Linked to Drug Use: Change in Drug Therapy May Resolve Symptoms". Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada. 139 (2): 70–73. doi:10.1177/171516350613900208.

- ↑ Preetha, A. and R. Banerjee, "Comparison of Artificial Saliva Substitutes, Trends in Biomaterials and Artificial Organs, Jan. 2005: 179.

- ↑ "Medications and Drugs," 6 May 2004, 25 Oct. 2009, <http://www.medicinenet.com/pilocarpine/article.htm>

- 1 2 Heyneman, Catherine A (February 1996). "Zinc Deficiency and Taste Disorders". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 30 (2): 186–187. PMID 8835055. doi:10.1177/106002809603000215.

- 1 2 3 4 Hong, Jae Hee, et al., "Taste and Odor Abnormalities in Cancer Patients," The Journal of Supportive Oncology, Mar./Apr. 2009: 59-64.

- 1 2 3 Yamagata, T; Nakamura, Y; Yamagata, Y; Nakanishi, M; Matsunaga, K; Nakanishi, H; Nishimoto, T; Minakata, Y; Mune, M; Yukawa, S (December 2003). "The pilot trial of the prevention of the increase in electrical taste thresholds by zinc containing fluid infusion during chemotherapy to treat primary lung cancer.". Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR. 22 (4): 557–63. PMID 15053297.

- ↑ Halyard, MY (2008). "Taste and smell alterations in cancer patients--real problems with few solutions.". The journal of supportive oncology. 7 (2): 68–9. PMID 19408460.

- 1 2 3 4 Bromley, Steven M., "Smell and Taste Disorders: A Primary Care Approach," American Family Physician 15 Jan. 2000, 23 Oct. 2009 <http://www.aafp.org/afp/20000115/427.html>

- 1 2 3 4 Castells, Xavier, et al., "Drug Points: Dysgeusia and Burning Mouth Syndrome by Eprosartan," British Medical Journal, 30 Nov. 2002: 1277.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sadasivam, Balakrishnan; Jhaj, Ratinder (February 2007). "Dysgeusia with amlodipine ? a case report". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 63 (2): 253–253. PMC 2000565

. PMID 17274793. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02727.x.

. PMID 17274793. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02727.x. - 1 2 3 University of Maryland Medical Center, "Alpha-lipoic Acid," 26 Oct. 2009 <http://www.umm.edu/altmed/articles/alpha-lipoic-000285.htm>

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Femiano, F; Scully, C; Gombos, F (December 2002). "Idiopathic dysgeusia; an open trial of alpha lipoic acid (ALA) therapy.". International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 31 (6): 625–8. PMID 12521319. doi:10.1054/ijom.2002.0276.

- ↑ Padala, Kalpana P.; Hinners, Cheryl K.; Padala, Prasad R. (14 July 2006). "Mirtazapine Therapy for Dysgeusia in an Elderly Patient". The Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 08 (03): 178–180. PMC 1540398

. PMID 16912823. doi:10.4088/PCC.v08n0310b.

. PMID 16912823. doi:10.4088/PCC.v08n0310b. - 1 2 Bicknell, JM; Wiggins, RV (October 1988). "Taste disorder from zinc deficiency after tonsillectomy.". The Western journal of medicine. 149 (4): 457–60. PMC 1026505

. PMID 3227690.

. PMID 3227690. - 1 2 3 National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, "Taste Disorders," 25 June 2008, 23 Oct. 2009 <http://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/smelltaste/taste.asp>

- ↑ The University of Connecticut Health Center, "Taste and Smell: Research," 26 Oct. 2009 <http://www.uchc.edu/uconntasteandsmell/research/index.html>