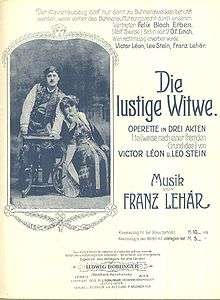

The Merry Widow

The Merry Widow (German: Die lustige Witwe) is an operetta by the Austro-Hungarian composer Franz Lehár. The librettists, Viktor Léon and Leo Stein, based the story – concerning a rich widow, and her countrymen's attempt to keep her money in the principality by finding her the right husband – on an 1861 comedy play, L'attaché d'ambassade (The Embassy Attaché) by Henri Meilhac.

The operetta has enjoyed extraordinary international success since its 1905 premiere in Vienna and continues to be frequently revived and recorded. Film and other adaptations have also been made. Well-known music from the score includes the "Vilja Song", "Da geh' ich zu Maxim" ("You'll Find Me at Maxim's"), and the "Merry Widow Waltz".

Background

In 1861, Henri Meilhac premiered a comic play in Paris, L'attaché d'ambassade (The Embassy Attaché), in which the Parisian ambassador of a poor German grand duchy, Baron Scharpf, schemes to arrange a marriage between his country's richest widow (a French woman) and a Count to keep her money at home, thus preventing economic disaster in the duchy. The play was soon adapted into German as Der Gesandschafts-Attaché (1862) and was given several successful productions. In early 1905, Viennese librettist Leo Stein came across the play and thought it would make a good operetta. He suggested this to one of his writing collaborators, Viktor Léon and to the manager of the Theater an der Wien, who was eager to produce the piece. The two adapted the play as a libretto and updated the setting to contemporary Paris, expanding the plot to reference an earlier relationship between the widow (this time a countrywoman) and Count, a native land moved from a dour German province to a colourful little Balkan state, the widow's admitting to an affair to protect the Baron's wife, and the Count's haven changed to the Parisian restaurant and nightclub Maxim's. They asked Richard Heuberger to compose the music, as he had a previous hit at the Theatre an der Wein with a Parisian-themed piece, Der Opernball (1898). He composed a draft of the score, but it was unsatisfactory, and he gladly left the project.[1]

The theatre's staff next suggested that Franz Lehár might compose the piece. Lehár had worked with Léon and Stein on Der Göttergatte the previous year. Although Léon doubted that Lehár could invoke an authentic Parisian atmosphere, he was soon enchanted by Lehar's first number for the piece, a bubbly galop melody for "Dummer, dummer Reitersmann". The score of Die Lustige Witwe was finished in a matter of months. The theatre engaged, for the leading roles, Mizzi Günther and Louis Treumann, who had starred as the romantic couple in other operettas in Vienna, including a production of Der Opernball and a previous Léon and Lehár success, Der Rastelbinder (1902). Both stars were so enthusiastic about the piece that they supplemented the theatre's low-budget production by paying for their own lavish costumes. During the rehearsal period, the theatre lost faith in the score and asked Lehár to withdraw it, but he refused.[1] The piece was given little rehearsal time on stage before its premiere.[2]

Original production

Die Lustige Witwe was first performed at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna on 30 December 1905, with Günther as Hanna, Treumann as Danilo, Siegmund Natzler as Baron Zeta and Annie Wünsch as Valencienne. It was a major success (after a couple of shaky weeks at the box-office), receiving good reviews and running for 483 performances.[2] The production was also toured in Austria in 1906. The operetta originally had no overture; Lehár wrote one for the 400th performance, but it is rarely used in productions of the operetta, as the original short introduction is preferred.[1] The Vienna Philharmonic performed the overture at Lehár's 70th birthday concert in April 1940.[3]

Roles and original cast

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 30 December 1905 (Conductor: Franz Lehár) |

|---|---|---|

| Hanna Glawari, a wealthy widow (title role) | soprano | Mizzi Günther |

| Count Danilo Danilovitsch, First Secretary of the Pontevedrin embassy and Hanna's former lover | tenor or lyric baritone | Louis Treumann |

| Baron Mirko Zeta, the Ambassador | baritone | Siegmund Natzler |

| Valencienne, Baron Zeta's wife | soprano | Annie Wünsch |

| Camille, Count de Rosillon, French attaché to the embassy, the Baroness's admirer | tenor | Karl Meister |

| Njegus, the Embassy Secretary | spoken | Oskar Sachs |

| Kromow, Pontevedrin embassy counsellor | baritone | Heinrich Pirl |

| Bogdanovitch, Pontevedrin consul | baritone | Fritz Albin |

| Sylviane, Bogdanovitch's wife | soprano | Bertha Ziegler |

| Raoul de St Brioche, French diplomat | tenor | Carlo Böhm |

| Vicomte Cascada, Latin diplomat | baritone | Leo von Keller |

| Olga, Kromow's wife | mezzo-soprano | Minna Schütz |

| Pritschitsch, Embassy consul | baritone | Julius Bramer |

| Praskowia, Pritschitsch's wife | mezzo-soprano | Lili Wista |

| Parisians and Pontevedrins, musicians and servants | ||

Synopsis

Act 1

The embassy in Paris of the poverty-stricken Balkan principality of Pontevedro is holding a ball to celebrate the birthday of the sovereign, the Grand Duke. Hanna Glawari, who has inherited twenty million francs from her late husband, is to be a guest at the ball and the ambassador, Baron Zeta, wants to ensure that she will marry another Pontevedrian and thereby keep her fortune in the country, saving Pontevedro from bankruptcy. Baron Zeta has in mind Count Danilo Danilovitsch, the First Secretary of the embassy, but his plans are not going well. Danilo is not at the party, so Zeta sends Njegus, the embassy secretary, to fetch him from Maxim's.

Danilo finally arrives and meets Hanna. It emerges they were in love before her marriage, but his uncle interrupted their romance because Hanna had absolutely nothing to her name. Although they still love each other, Danilo refuses to court Hanna because of her fortune and Hanna vows she will not marry him until he says "I love you".

Meanwhile, Baron Zeta's wife Valencienne has been flirting with the French attaché to the embassy, Count Camille de Rosillon, who writes "I love you" on her fan. Valencienne puts off Camille's advances, saying that she is a respectable wife. However, they lose the incriminating fan, which is found by embassy counsellor Kromow, who jealously fears the fan belongs to his wife, Olga, and gives it to Baron Zeta. Not recognising Valencienne's fan, Baron Zeta decides to return the fan to Olga, in spite of Valencienne's desperate offers to take the fan and return it herself.

On his way to see Olga, the Baron meets Danilo, and his diplomatic mission takes precedence over the fan. The Baron orders Danilo to marry Hanna. Refusing to accede to the Baron's demand, Danilo offers to eliminate any non-Pontevedrian suitors as a compromise.

The "Ladies' Choice" dance is about to start, and all the men hover around Hanna, hoping to be her choice of partner. Valencienne hatches an idea to get Camille to marry Hanna so that he will cease to be a temptation for her, and therefore volunteers Camille as a partner for Hanna in her "Ladies' Choice" dance. Danilo goes to the ballroom to round up some of the other ladies to claim dances with the hopeful suitors of Hanna. Even after the ladies have made their choices, there are still some suitors left behind. Hanna chooses the one man who is apparently not interested in dancing with her – Danilo. Danilo refuses to dance, but claims the dance anyway. He offers his dance with Hanna for sale for ten thousand francs, with the proceeds to benefit charity. This extinguishes the interest of the would-be suitors in the dance. After they have left, Danilo attempts to dance with Hanna. Annoyed at his previous evasive maneuver, she refuses to dance with him. Nonchalantly, Danilo begins to waltz by himself, eventually wearing down Hanna's resistance, and she falls into his arms.

Act 2

The next evening, everyone is dressed in Pontevedrian clothing, at a party in the garden at Hanna's house, to celebrate the birthday of the Grand Duke in Pontevedrian fashion. Hanna entertains by singing an old Pontevedrian song, "Vilja" ("Es lebt' eine Vilja, ein Waldmägdelein" – "There lived a Vilja, a maid of the woods"). Meanwhile, Baron Zeta fears that Camille is a threat to his plan for Hanna to marry a Pontevedrian. Still not recognising the fan as Valencienne's, the Baron orders Danilo to find out the identity of its owner, whom he assumes to be Camille's married lover. A meeting is arranged between Zeta, Danilo and Njegus, to discuss the identity of the owner of the fan and also the problem with regard to the widow, with the meeting to be held that evening in Hanna's garden pavilion. Hanna sees the fan, and thinks the message on it is Danilo's declaration of love for her, which he denies. Danilo's inquiries about the identity of the owner of the fan result in revelations of the details of the infidelities of some of the wives of Embassy personnel, but do not reveal the identity of the owner of the fan.

That evening, Camille and Valencienne meet in the garden. Valencienne continues to resist Camille's advances, declaring that they must part. Camille begs for a keepsake, and discovers the fan, which Danilo had accidentally left behind, after his inquiries. Camille begs Valencienne to let him keep the fan as the keepsake, and Valencienne agrees, after writing "I'm a highly respectable wife" on the fan in response to Camille's earlier written declaration of "I love you". Camille persuades Valencienne to enter the same pavilion – in which Danilo, the Baron and Njegus had arranged to meet – so that they can say their goodbyes in private. Njegus, who arrives first for the meeting, discovers that Camille is in the pavilion with Valencienne. Njegus locks the door to the pavilion when Danilo and Baron Zeta arrive, and delays their entry to the pavilion. The Baron peeps through the keyhole to see what lovers may be inside and is upset when he recognises his own wife. Njegus arranges with Hanna to change places with Valencienne. Camille leaves the pavilion followed by Hanna, confounding the Baron when they appear. Hanna announces that she is to marry Camille, leaving the Baron distraught at the thought of losing the Pontevedrian millions and Valencienne distraught at losing Camille. Danilo is furious and tells the story of a Princess who cheated on her Prince ("Es waren zwei Königskinder") and then storms off to seek the distractions at Maxim's. Hanna realises that his anger at the announcement of her engagement shows that Danilo loves her and rejoices among the general despair.

Act 3

Act 3 is set at a theme party in Hanna's ballroom, which she has decorated as Maxim's, complete with Maxim's grisettes (can-can dancers). Valencienne, who has dressed herself as a grisette, entertains the guests ("Ja, wir sind es, die Grisetten"). When Danilo arrives, having found the real Maxim's empty, he tells Hanna to give up Camille for the sake of the country. Much to Danilo's delight, Hanna tells him that she was never engaged to Camille, but that she was protecting the reputation of a married woman. Danilo is ready to declare his love for Hanna, and is on the point of doing so when he remembers her money, and stops himself. When Njegus produces the fan, which he had picked up earlier, Baron Zeta suddenly remembers that the fan belongs to Valencienne. Baron Zeta swears to divorce his wife and marry the widow himself, but Hanna tells him that she loses her fortune if she remarries. Hearing this, Danilo confesses his love for her and asks Hanna to marry him, and Hanna triumphantly points out that she will lose her fortune only because it will become the property of her husband. Valencienne produces the fan and assures Baron Zeta of her fidelity by reading out what she had replied to Camille's declaration: "Ich bin eine anständige Frau" ("I'm a respectable wife"); and all ends happily.

Subsequent productions

The operetta was produced in 1906 in Hamburg's Neues Operetten-Theater, Berlin's Berliner Theater (starring Gustav Matzner as Danilo and Marie Ottmann as Hanna, who made the first complete recording in 1907), and Budapest's Magyar Színház in a faithful Hungarian translation. The piece became an international sensation, and translations were quickly made into various languages: in 1907, Buenos Aires theatres were playing at least five productions, each in a different language. Productions also swiftly followed in Stockholm, Copenhagen, Milan, Moscow and Madrid, among other places. It was eventually produced in every city with a theatre industry. Bernard Grün, in his book Gold and Silver: The Life and Times of Franz Lehar, estimates that The Merry Widow was performed about half a million times in its first sixty years.[4] Global sheet music sales and recordings totalled tens of millions of dollars. According to theatre writer John Kenrick, no other play or musical up to the 1960s had enjoyed such international commercial success.[5]

English adaptations

In its English adaptation by Basil Hood, with lyrics by Adrian Ross, The Merry Widow became a sensation at Daly's Theatre in London, opening on 8 June 1907, starring Lily Elsie and Joseph Coyne and featuring George Graves as the Baron, Robert Evett as Camille and W. H. Berry as Nisch, with costumes by Lucile and Percy Anderson.[6] Gabrielle Ray was a replacement as the Maxim's dancer Frou-Frou.[7] It was produced by George Edwardes. The production ran for an extraordinary 778 performances in London and toured extensively in Great Britain.[5]

The adaptation renamed many of the characters, to avoid offense to Montenegro, where the royal family's surname was Njegus, the crown prince was named Danilo, and Zeta was the principal founding state. Hood changed the name of the principality to Marsovia, Danilo is promoted to the title of Prince, Hannah is Sonia, the Baron is Popoff, Njegus is Nisch, Camille's surname is de Jolidon and Valencienne is Natalie, among other changes.[6] The final scene was relocated into Maxim's itself, rather than the original theme-party setting, to take further advantage of the fame of the nightclub. Graves ad-libbed extensive "business" in the role of the Baron. Edwardes engaged Lehár to write two new songs, one of which, "Quite Parisien" (a third act solo for Nisch) is still used.[5] Lehár also made changes for a Berlin production in the 1920s, but the definitive version of the score is basically that of the original production.[5]

The first American production opened on 21 October 1907 at the New Amsterdam Theatre on Broadway for another very successful run of 416 performances, and was reproduced by multiple touring companies across the US, all using the Hood/Ross libretto. It was produced by Henry Wilson Savage. The New York cast starred Ethel Jackson as Sonia and Donald Brian as Danilo. The operetta first played in Australia in 1908 using the Hood/Ross libretto. Since then, it has been staged frequently in English. It was revived in London's West End in 1923, running for 239 performances, and in 1924 and 1932. A 1943 revival ran for 302 performances. Most of these productions featured Graves as Popoff. Madge Elliott and Cyril Ritchard starred in the 1944 production, while June Bronhill and Thomas Round led the 1958 cast and recording. Lizbeth Webb and John Rhys Evans starred in a brief 1969 revival.[5] Revivals were mounted in major New York theatres in 1921, 1929, 1931 and 1943–1944. The last of these starred Marta Eggerth and her husband Jan Kiepura, with sets by Howard Bay and choreography by George Balanchine. It ran for 322 performances at the Majestic Theatre and returned the next season at the New York City Center for another 32 performances.[8]

Glocken Verlag Ltd, London, published two different English translation editions in 1958. One English-language libretto is by Phil Park, which was adapted and arranged by Ronald Hanmer. The other is by Christopher Hassall, based on the edition by Ludwig Doblinger, Vienna. The Park version is a whole-tone lower than the original. Danilo and Hanna's hummed waltz theme becomes a chorus number, and the ending of the "Rosebud Romance" is sung mostly in unison rather than as a conversation. In the Hassall version, the action of act 3 takes place at Maxim's. Valencienne and the other Embassy wives arrive to seek out Danilo and convince him to return to Hanna, closely followed by their husbands, seeking to achieve the same purpose. The Grisettes, Parisian cabaret girls, make a grand entrance, led by the voluptuous ZoZo. Zeta finds the brokenhearted Danilo, and as they argue, Hanna enters. Hanna, Danilo and Zeta separately bribe the Maitre'd to clear the room so Hanna and Danilo can be alone. Danilo sets aside his pride and asks Hanna to give up Camille for the sake of the country. Much to Danilo's delight, Hanna tells him that she was never engaged to Camille, but that she was protecting the reputation of a married woman. Danilo is ready to declare his love for Hanna, and is on the point of doing so when he remembers her money, and stops himself. When Njegus produces the fan, which he had picked up earlier, Baron Zeta suddenly realizes that the fan belongs to Valencienne. Baron Zeta swears to divorce his wife and marry the widow himself, but Hanna tells him that she loses her fortune if she remarries. Hearing this, Danilo confesses his love for her and asks Hanna to marry him, and Hanna triumphantly points out that she will lose her fortune only because it will become the property of her husband. Valencienne produces the fan and assures Baron Zeta of her fidelity by reading out what she had replied to Camille's declaration: "I'm a highly respectable wife".

In the 1970s, the Light Opera of Manhattan, a year-round professional light opera repertory company in New York City, commissioned Alice Hammerstein Mathias, the daughter of Oscar Hammerstein II, to create a new English adaptation, which was revived many times until the company closed at the end of the 1980s.[9][10] Essgee Entertainment staged productions of The Merry Widow in capital cities around Australia during 1998 and 1999. A prologue was added featuring a narrative by Jon English and a ballet introducing the earlier romance of Anna and Danilo. The production opened in Brisbane, with Jeffrey Black as Danilo, Helen Donaldson as "Anna", Simon Gallaher as Camille and English as Baron Zeta. In some performances, during the production's Brisbane run, Jason Barry-Smith appeared as Danilo. In Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide in 1999, John O'May appeared as Danilo, Marina Prior as "Hanna", Max Gillies as Zeta, Gallaher as Camille and Donaldson as Valencienne.

Numerous opera companies have mounted the operetta.[5] New York City Opera mounted several productions from the 1950s through the 1990s, including a lavish 1977 production starring Beverly Sills and Alan Titus with a new translation by Sheldon Harnick. An Australian Opera production starred Joan Sutherland, and PBS broadcast a production by the San Francisco Opera in 2002, among numerous other broadcasts.[11] The Metropolitan Opera had mounted the opera 18 times by 2003.[12] The first performance by The Royal Opera in London was in 1997.[13] A new English translation by Justin Fleming was staged by West Australian Opera in July 2017 at His Majesty's Theatre, Perth.[14]

French and German

The first production in Paris was at the Théâtre Apollo on 28 April 1909 as La Veuve joyeuse. Although Parisians were worried about how their city would be portrayed in the operetta, the Paris production was well received and ran for 186 performances. In this translation, Hanna is an American raised in "Marsovie" named "Missia". Danilo was a prince with gambling debts. The third act was set in Maxim's. The following year, the operetta played in Brussels.[5]

The Merry Widow is frequently revived in Vienna and is part of the Vienna Volksopera's repertory. The Volksopera released a complete live performance on CD, interpolating the "Can-Can" from Offenbach's Orpheus in the Underworld, which was copied in many other productions worldwide.[5] Best known as Danilo in the German version was the actor Johannes Heesters, who played the part thousands of times for over thirty years.

Recordings

The operetta has been recorded both live and in the studio many times, and several video recordings have been made.[15][16] In 1906, the original Hanna and Danilo, Mizzi Günther and Louis Treumann, recorded their arias and duets, and also some numbers written for Camille and Valencienne; CD transfers were made in 2005.[17] The first recording of a substantially complete version of the score was made in 1907 with Marie Ottmann and Gustav Matzner in the lead roles.[18] After that, excerpts appeared periodically on disc, but no new full recording was issued until 1950, when Columbia Records released a set sung in English with Dorothy Kirsten and Robert Rounseville.[18]

In 1953, EMI's Columbia label released a near-complete version[19] produced by Walter Legge, conducted by Otto Ackermann, with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf as Hanna, Erich Kunz as Danilo, Nicolai Gedda as Camille and Emmy Loose as Valencienne. It was sung in German, with abridged spoken dialogue.[20] Loose sang Valencienne again for Decca in the first stereophonic recording, produced in 1958 by John Culshaw, with Hilde Gueden, Per Grundén and Waldemar Kmentt in the other main roles, and the Vienna Philharmonic conducted by Robert Stolz.[21] A second recording with Schwarzkopf as Hanna was issued by Columbia in 1963; the other main roles were sung by Eberhard Wächter, Gedda and Hanny Steffek.[18] This set, conducted by Lovro von Matačić, has been reissued on CD in EMI's "Great Recordings of the Century" series.[22] Among later complete or substantially complete sets are those conducted by Herbert von Karajan with Elizabeth Harwood as Hanna (1972); Franz Welser-Möst with Felicity Lott (1993); and John Eliot Gardiner with Cheryl Studer (1994).[18]

The Ackermann recording received the highest available rating in the 1956 The Record Guide[20] and the later EMI set under Matačić is highly rated by the 2008 The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music,[22] but Alan Blyth in his Opera on CD regrets the casting of a baritone as Danilo in both sets and prefers the 1958 Decca version.[23] Among the filmed productions on DVD, the Penguin Guide recommends the one from the San Francisco Opera, recorded live in 2001, conducted by Erich Kunzel and directed by Lotfi Mansouri, with Yvonne Kenny as Hanna and Bo Skovhus as Danilo.[22]

Adaptations

Ballet version

With the permission of the Franz Lehár Estate, Sir Robert Helpmann adapted the operetta's plot scenario, while John Lanchbery and Alan Abbot adapted the operetta's music and composed additional music, for a three-act ballet. The Merry Widow ballet was first performed on 13 November 1975 by The Australian Ballet.[24]

Film versions

Various films have been made that are based loosely on the plot of the operetta[11]

- Hungarian 1918 silent version by Michael Curtiz

- 1925 silent version by Erich von Stroheim, with John Gilbert as Danilo and Mae Murray as Hanna

- 1934 black-and-white version, by Ernst Lubitsch, starring Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald

- 1952 version in Technicolor starring Lana Turner and Fernando Lamas

- 1962 Austrian version by Werner Jacobs

Uses in media

The theme of "Da geh' ich zu Maxim" was ironically cited by Shostakovich in the first movement of his Symphony No. 7 and repeated in the fourth movement of Béla Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra,[25][26]

"The Merry Widow Waltz" is a recurring theme in the 1943 films Shadow of a Doubt, directed by Alfred Hitchcock and scored by Dimitri Tiomkin,[27] and Heaven Can Wait by Ernst Lubitsch.[28]

Notes

- 1 2 3 Kenrick, John. "The Merry Widow 101: History of a Hit". Musicals101.com, 2004, accessed 24 January 2016

- 1 2 Baranello, Micaela. "Die lustige Witwe and the Creation of the Silver Age of Viennese Operetta", Academia.edu, 2014, accessed January 24, 2016

- ↑ Göran Forsling, review of Naxos reissue of 1953 Ackermann recording of the operetta.

- ↑ Grün, Bernard. Gold and Silver: The Life and Times of Franz Lehar, New York: David McKay Company (1970), p. 129

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kenrick, John. "The Merry Widow 101 – History of a Hit: Part II", Musicals101.com, 2004, accessed 28 July 2011

- 1 2 Original theatre programme from Daly's Theatre, available at "The Merry Widow. June 8th 1907", Miss Lily Elsie website, accessed 24 January 2016

- ↑ Gillan, Don. "Gabrielle Ray biography", at the Stage Beauty website

- ↑ The Merry Widow, Internet Broadway Database, accessed 24 January 2016

- ↑ "Alice Hammerstein Mathias". Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization, accessed May 10, 2011

- ↑ Kenrick, John. Article on the history of LOOM, Musicals101.com

- 1 2 Kenrick, John. "The Merry Widow 101 – History of a Hit: Part III", Musicals101.com, 2004, accessed 24 January 2016

- ↑ Kerner, Leighton. The Merry Widow, Opera News, 22 December 2003

- ↑ "The Merry Widow (1997)", Royal Opera House Collections Online, accessed 27 May 2012.

- ↑ Appleby, Rosalind. "Review: The Merry Widow (West Australian Opera)", Limelight magazine,17 July 2017

- ↑ Die lustige Witwe recordings. operadis-opera-discography.org.uk, accessed 10 May 2011

- ↑ Kenrick, John. "Merry Widow 101: Discography". Musicals101.com, 2006, accessed 28 July 2011

- ↑ In addition to her own numbers, Gunther took over Valencienne's " Ich bin eine anständ'ge Frau" as a solo, and she and Treumann recorded Camille and Valencienne's duet, "Das ist der Zauber der Stillen Häuslichkeit". See: O'Connor, Patrick. "A Viennese Whirl", Gramophone, October 2005, p. 49

- 1 2 3 4 O'Connor, Patrick. "A Viennese Whirl", Gramophone, October 2005, pp. 48–52

- ↑ It omits "Das ist der Zauber der Stillen Häuslichkeit": see O'Connor, Patrick. "A Viennese Whirl", Gramophone, October 2005, p. 50

- 1 2 Sackville-West, pp. 401–402

- ↑ Stuart, Philip. "Decca Classical, 1929–2009". Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music, July 2009, accessed 11 May 2011

- 1 2 3 March, p. 698

- ↑ Blyth, pp. 138–139

- ↑ Weinberger, Joseph. "The Creation of The Merry Widow Ballet"

- ↑ "Saturday 18th May 2002". London Shostakovich Orchestra, accessed 4 January 2011

- ↑ Mostel, Raphael. "The Merry Widow's Fling With Hitler", TabletMag.com, 30 December 2014, accessed 11 November 2016

- ↑ Crogan, Patrick. "Between Heads: Thoughts on the Merry Widow Tune in Shadow of a Doubt", Senses of Cinema, May 2000, accessed May 23, 2014

- ↑ Alpert, Robert. "Ernst Lubitsch and Nancy Meyers: A Study on Movie Love in the Classic and Post-Modernist Traditions", Senses of Cinema, March 2012, accessed 3 July 2014

Sources

- Blyth, Alan. Opera on CD. London: Kyle Cathie, 1992. ISBN 1-85626-103-4

- Bordman, Gerald. American Operetta. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.

- Gänzl, Kurt. The Merry Widow in The Encyclopedia of Musical Theatre (3 volumes). New York: Schirmer Books, 2001.

- Grun, Bernard. Gold and Silver: The Life and Times of Franz Lehár. New York: David McKay Co., 1970.

- March, Ivan (ed). Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music 2008. London: Penguin Books, 2007. ISBN 0-14-103336-3

- Sackville-West, Edward, and Desmond Shawe-Taylor. The Record Guide. London: Collins, 1956. OCLC 500373060

- Traubner, Richard. Operetta: A Theatrical History. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1983

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Merry Widow. |

- Libretto (German, English)

- Scores at IMSLP (German, English)

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005).[http://www.amadeusonline.net/almanacco?r=&alm_giorno=30&alm_mese=12&alm_anno=1905&alm_testo=Die_lustige_Witwe "Die lustige Witwe, 30 December 1905"]. Almanacco Amadeus (in Italian).

- The Merry Widow: A Brief History at Musicals101.com

- John Culme's Footlight Notes site (2004)

- Comprehensive site celebrating centenary of the work, edited by Andrew Lamb

- Photos from productions of The Merry Widow, New York Public Library

- IMDb search page for "Merry Widow"

- List of theatre runs showing the number of performances of The Merry Widow and Die Lustige Witwe in each major run

- Clips from a performance at the Moscow Operetta Theatre