Mendelian inheritance

| Part of a series on |

| Genetics |

|---|

|

| Key components |

| History and topics |

| Research |

|

| Personalized medicine |

| Personalized medicine |

|

Mendelian inheritance[help 1] is a type of biological inheritance that follows the laws originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866 and re-discovered in 1900. These laws were initially very controversial. When Mendel's theories were integrated with the Boveri–Sutton chromosome theory of inheritance by Thomas Hunt Morgan in 1915, they became the core of classical genetics. Ronald Fisher later combined these ideas with the theory of natural selection in his 1930 book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, putting evolution onto a mathematical footing and forming the basis for population genetics and the modern evolutionary synthesis.[1]

History

The principles of Mendelian inheritance were named for and first derived by Gregor Johann Mendel, a nineteenth-century Austrian monk[2] who formulated his ideas after conducting simple hybridization experiments with pea plants (Pisum sativum) he had planted in the garden of his monastery.[3] Between 1856 and 1863, Mendel cultivated and tested some 5,000 pea plants. From these experiments, he induced two generalizations which later became known as Mendel's Principles of Heredity or Mendelian inheritance. He described these principles in a two-part paper, Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden (Experiments on Plant Hybridization), that he read to the Natural History Society of Brno on 8 February and 8 March 1865, and which was published in 1866.[4]

Mendel's conclusions were largely ignored by the vast majority. Although they were not completely unknown to biologists of the time, they were not seen as generally applicable, even by Mendel himself, who thought they only applied to certain categories of species or traits. A major block to understanding their significance was the importance attached by 19th-century biologists to the apparent blending of inherited traits in the overall appearance of the progeny, now known to be due to multi-gene interactions, in contrast to the organ-specific binary characters studied by Mendel.[3] In 1900, however, his work was "re-discovered" by three European scientists, Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns, and Erich von Tschermak. The exact nature of the "re-discovery" has been somewhat debated: De Vries published first on the subject, mentioning Mendel in a footnote, while Correns pointed out Mendel's priority after having read De Vries' paper and realizing that he himself did not have priority. De Vries may not have acknowledged truthfully how much of his knowledge of the laws came from his own work and how much came only after reading Mendel's paper. Later scholars have accused Von Tschermak of not truly understanding the results at all.[3]

Regardless, the "re-discovery" made Mendelism an important but controversial theory. Its most vigorous promoter in Europe was William Bateson, who coined the terms "genetics" and "allele" to describe many of its tenets. The model of heredity was highly contested by other biologists because it implied that heredity was discontinuous, in opposition to the apparently continuous variation observable for many traits. Many biologists also dismissed the theory because they were not sure it would apply to all species. However, later work by biologists and statisticians such as Ronald Fisher showed that if multiple Mendelian factors were involved in the expression of an individual trait, they could produce the diverse results observed, and thus showed that Mendelian genetics is compatible with natural selection. Thomas Hunt Morgan and his assistants later integrated Mendel's theoretical model with the chromosome theory of inheritance, in which the chromosomes of cells were thought to hold the actual hereditary material, and created what is now known as classical genetics, a highly successful foundation which eventually cemented Mendel's place in history.

Mendel's findings allowed scientists such as Fisher and J.B.S. Haldane to predict the expression of traits on the basis of mathematical probabilities. An important aspect of Mendel's success can be traced to his decision to start his crosses only with plants he demonstrated were true-breeding. He also only measured absolute (binary) characteristics, such as color, shape, and position of the seeds, rather than quantitatively variable characteristics. He expressed his results numerically and subjected them to statistical analysis. His method of data analysis and his large sample size gave credibility to his data. He also had the foresight to follow several successive generations (F2, F3) of pea plants and record their variations. Finally, he performed "test crosses" (backcrossing descendants of the initial hybridization to the initial true-breeding lines) to reveal the presence and proportions of recessive characters. Without his diligence and careful attention to procedure and detail, Mendel's work would have had a much smaller impact on the world of genetics.

Mendel's laws

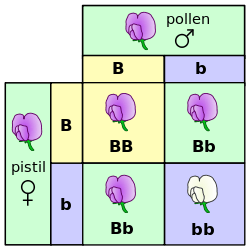

Mendel discovered that, when he crossed purebred white flower and purple flower pea plants (the parental or P generation), the result was not a blend. Rather than being a mix of the two, the offspring (known as the F1 generation) was purple-flowered. When Mendel self-fertilized the F1 generation pea plants, he obtained a purple flower to white flower ratio in the F2 generation of 3 to 1. The results of this cross are tabulated in the Punnett square to the right.

He then conceived the idea of heredity units, which he called "factors". Mendel found that there are alternative forms of factors—now called genes—that account for variations in inherited characteristics. For example, the gene for flower color in pea plants exists in two forms, one for purple and the other for white. The alternative "forms" are now called alleles. For each biological trait, an organism inherits two alleles, one from each parent. These alleles may be the same or different. An organism that has two identical alleles for a gene is said to be homozygous for that gene (and is called a homozygote). An organism that has two different alleles for a gene is said be heterozygous for that gene (and is called a heterozygote).

Mendel also hypothesized that allele pairs separate randomly, or segregate, from each other during the production of gametes: egg and sperm. Because allele pairs separate during gamete production, a sperm or egg carries only one allele for each inherited trait. When sperm and egg unite at fertilization, each contributes its allele, restoring the paired condition in the offspring. This is called the Law of Segregation. Mendel also found that each pair of alleles segregates independently of the other pairs of alleles during gamete formation. This is known as the Law of Independent Assortment.[5]

The genotype of an individual is made up of the many alleles it possesses. An individual's physical appearance, or phenotype, is determined by its alleles as well as by its environment. The presence of an allele does not mean that the trait will be expressed in the individual that possesses it. If the two alleles of an inherited pair differ (the heterozygous condition), then one determines the organism’s appearance and is called the dominant allele; the other has no noticeable effect on the organism’s appearance and is called the recessive allele. Thus, in the example above dominant purple flower allele will hide the phenotypic effects of the recessive white flower allele. This is known as the Law of Dominance but it is not a transmission law, dominance has to do with the expression of the genotype and not its transmission. The upper case letters are used to represent dominant alleles whereas the lowercase letters are used to represent recessive alleles.

| Law | Definition |

|---|---|

| Law of segregation | During gamete formation, the alleles for each gene segregate from each other so that each gamete carries only one allele for each gene. |

| Law of independent assortment | Genes for different traits can segregate independently during the formation of gametes. |

| Law of dominance | Some alleles are dominant while others are recessive; an organism with at least one dominant allele will display the effect of the dominant allele. |

In the pea plant example above, the capital "P" represents the dominant allele for purple flowers and lowercase "p" represents the recessive allele for white flowers. Both parental plants were true-breeding, and one parental variety had two alleles for purple flowers (PP) while the other had two alleles for white flowers (pp). As a result of fertilization, the F1 hybrids each inherited one allele for purple flowers and one for white. All the F1 hybrids (Pp) had purple flowers, because the dominant P allele has its full effect in the heterozygote, while the recessive p allele has no effect on flower color. For the F2 plants, the ratio of plants with purple flowers to those with white flowers (3:1) is called the phenotypic ratio. The genotypic ratio, as seen in the Punnett square, is 1 PP : 2 Pp : 1 pp.

Law of Segregation of genes (the "First Law")

(1) Parental generation.

(2) F1 generation.

(3) F2 generation. Dominant (red) and recessive (white) phenotype look alike in the F1 (first) generation and show a 3:1 ratio in the F2 (second) generation.

The Law of Segregation states that every individual organism contains two alleles for each trait, and that these alleles segregate (separate) during meiosis such that each gamete contains only one of the alleles.[6] An offspring thus receives a pair of alleles for a trait by inheriting homologous chromosomes from the parent organisms: one allele for each trait from each parent.[6]

Molecular proof of this principle was subsequently found through observation of meiosis by two scientists independently, the German botanist Oscar Hertwig in 1876, and the Belgian zoologist Edouard Van Beneden in 1883. Paternal and maternal chromosomes get separated in meiosis and the alleles with the traits of a character are segregated into two different gametes. Each parent contributes a single gamete, and thus a single, randomly successful allele copy to their offspring and fertilization.

Law of Independent Assortment (the "Second Law")

The Law of Independent Assortment states that alleles for separate traits are passed independently of one another from parents to offspring.[7] That is, the biological selection of an allele for one trait has nothing to do with the selection of an allele for any other trait. Mendel found support for this law in his dihybrid cross experiments (Fig. 1). In his monohybrid crosses, an idealized 3:1 ratio between dominant and recessive phenotypes resulted. In dihybrid crosses, however, he found a 9:3:3:1 ratios (Fig. 2). This shows that each of the two alleles is inherited independently from the other, with a 3:1 phenotypic ratio for each.

Independent assortment occurs in eukaryotic organisms during meiotic prophase I, and produces a gamete with a mixture of the organism's chromosomes. The physical basis of the independent assortment of chromosomes is the random orientation of each bivalent chromosome along the metaphase plate with respect to the other bivalent chromosomes. Along with crossing over, independent assortment increases genetic diversity by producing novel genetic combinations.

There are many violations of independent assortment due to genetic linkage.

Of the 46 chromosomes in a normal diploid human cell, half are maternally derived (from the mother's egg) and half are paternally derived (from the father's sperm). This occurs as sexual reproduction involves the fusion of two haploid gametes (the egg and sperm) to produce a new organism having the full complement of chromosomes. During gametogenesis—the production of new gametes by an adult—the normal complement of 46 chromosomes needs to be halved to 23 to ensure that the resulting haploid gamete can join with another gamete to produce a diploid organism. An error in the number of chromosomes, such as those caused by a diploid gamete joining with a haploid gamete, is termed aneuploidy.

In independent assortment, the chromosomes that result are randomly sorted from all possible maternal and paternal chromosomes. Because zygotes end up with a random mix instead of a pre-defined "set" from either parent, chromosomes are therefore considered assorted independently. As such, the zygote can end up with any combination of paternal or maternal chromosomes. Any of the possible variants of a zygote formed from maternal and paternal chromosomes will occur with equal frequency. For human gametes, with 23 pairs of chromosomes, the number of possibilities is 223 or 8,388,608 possible combinations.[8] The zygote will normally end up with 23 chromosomes pairs, but the origin of any particular chromosome will be randomly selected from paternal or maternal chromosomes. This contributes to the genetic variability of progeny.

Law of Dominance (the "Third Law")

Mendel's Law of Dominance states that recessive alleles will always be masked by dominant alleles. Therefore, a cross between a homozygous dominant and a homozygous recessive will always express the dominant phenotype, while still having a heterozygous genotype. Law of Dominance can be explained easily with the help of a mono hybrid cross experiment:- In a cross between two organisms pure for any pair (or pairs) of contrasting traits (characters), the character that appears in the F1 generation is called "dominant" and the one which is suppressed (not expressed) is called "recessive." Each character is controlled by a pair of dissimilar factors. Only one of the characters expresses. The one which expresses in the F1 generation is called Dominant. It is important to note however, that the law of dominance is significant and true but is not universally applicable.

According to the latest revisions, only two of these rules are considered to be laws. The third one is considered as a basic principle but not a genetic law of Mendel.

Mendelian trait

A Mendelian trait is one that is controlled by a single locus in an inheritance pattern. In such cases, a mutation in a single gene can cause a disease that is inherited according to Mendel's laws. Examples include sickle-cell anemia, Tay-Sachs disease, cystic fibrosis and xeroderma pigmentosa. A disease controlled by a single gene contrasts with a multi-factorial disease, like arthritis, which is affected by several loci (and the environment) as well as those diseases inherited in a non-Mendelian fashion.

Non-Mendelian inheritance

Mendel explained inheritance in terms of discrete factors—genes—that are passed along from generation to generation according to the rules of probability. Mendel's laws are valid for all sexually reproducing organisms, including garden peas and human beings. However, Mendel's laws stop short of explaining some patterns of genetic inheritance. For most sexually reproducing organisms, cases where Mendel's laws can strictly account for the patterns of inheritance are relatively rare. Often, the inheritance patterns are more complex.

The F1 offspring of Mendel's pea crosses always looked like one of the two parental varieties. In this situation of "complete dominance," the dominant allele had the same phenotypic effect whether present in one or two copies. But for some characteristics, the F1 hybrids have an appearance in between the phenotypes of the two parental varieties. A cross between two four o'clock (Mirabilis jalapa) plants shows this common exception to Mendel's principles. Some alleles are neither dominant nor recessive. The F1 generation produced by a cross between red-flowered (RR) and white flowered (WW) Mirabilis jalapa plants consists of pink-colored flowers (RW). Which allele is dominant in this case? Neither one. This third phenotype results from flowers of the heterzygote having less red pigment than the red homozygotes. Cases in which one allele is not completely dominant over another are called incomplete dominance. In incomplete dominance, the heterozygous phenotype lies somewhere between the two homozygous phenotypes.

A similar situation arises from codominance, in which the phenotypes produced by both alleles are clearly expressed. For example, in certain varieties of chicken, the allele for black feathers is codominant with the allele for white feathers. Heterozygous chickens have a color described as "erminette", speckled with black and white feathers. Unlike the blending of red and white colors in heterozygous four o'clocks, black and white colors appear separately in chickens. Many human genes, including one for a protein that controls cholesterol levels in the blood, show codominance, too. People with the heterozygous form of this gene produce two different forms of the protein, each with a different effect on cholesterol levels.

In Mendelian inheritance, genes have only two alleles, such as a and A. In nature, such genes exist in several different forms and are therefore said to have multiple alleles. A gene with more than two alleles is said to have multiple alleles. An individual, of course, usually has only two copies of each gene, but many different alleles are often found within a population. One of the best-known examples is coat color in rabbits. A rabbit's coat color is determined by a single gene that has at least four different alleles. The four known alleles display a pattern of simple dominance that can produce four coat colors. Many other genes have multiple alleles, including the human genes for ABO blood type.

Furthermore, many traits are produced by the interaction of several genes. Traits controlled by two or more genes are said to be polygenic traits. Polygenic means "many genes." For example, at least three genes are involved in making the reddish-brown pigment in the eyes of fruit flies. Polygenic traits often show a wide range of phenotypes. The broad variety of skin color in humans comes about partly because at least four different genes probably control this trait.

See also

- List of Mendelian traits in humans

- Mendelian diseases (monogenic disease)

- Mendelian error

- Particulate inheritance

- Punnett square

- Introduction to genetics

Notes

- ↑ Pronunciation: /mɛnˈdiːljən/, /-ˈdiːliən/.

References

- ↑ Grafen, Alan; Ridley, Mark (2006). Richard Dawkins: How A Scientist Changed the Way We Think. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-19-929116-0.

- ↑ E. B. Ford (1960). Mendelism and Evolution (seventh ed.). Methuen & Co (London), and John Wiley & Sons (New York). p. 1.

- 1 2 3 Henig, Robin Marantz (2009). The Monk in the Garden : The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, the Father of Modern Genetics. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-97765-7.

The article, written by an Austrian monk named Gregor Johann Mendel...

- ↑ See Mendel's paper in English: Gregor Mendel (1865). "Experiments in Plant Hybridization".

- ↑ "Pearson - The Biology Place". www.phschool.com. Retrieved 2017-04-26.

- 1 2 Bailey, Regina (5 November 2015). "Mendel's Law of Segregation". about education. About.com. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ↑ Bailey, Regina. "Independent Assortment". about education. About.com. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ Perez, Nancy. "Meiosis". Retrieved 15 February 2007.

Notes

- Peter J. Bowler (1989). The Mendelian Revolution: The Emergence of Hereditarian Concepts in Modern Science and Society. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Atics, Jean. Genetics: The life of DNA. ANDRNA press.

- Reece, Jane B., and Neil A. Campbell. "Mendel and the Gene Idea." Campbell Biology. 9th ed. Boston: Benjamin Cummings / Pearson Education, 2011. 265. Print.