Memphis, Egypt

| منف | |

|

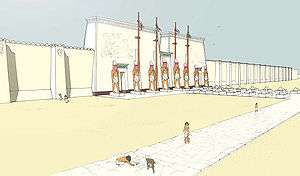

Ruins of the pillared hall of Rameses II at Mit Rahina | |

Shown within Egypt | |

| Location | Mit Rahina, Giza Governorate, Egypt |

|---|---|

| Region | Lower Egypt |

| Coordinates | 29°50′41″N 31°15′3″E / 29.84472°N 31.25083°ECoordinates: 29°50′41″N 31°15′3″E / 29.84472°N 31.25083°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Unknown, was already in existence during Iry-Hor's reign[1] |

| Founded | Earlier than 31st century BC |

| Abandoned | 7th century AD |

| Periods | Early Dynastic Period to Early Middle Ages |

| Official name | Memphis and its Necropolis – the Pyramid Fields from Giza to Dahshur |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, vi |

| Designated | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Reference no. | 86 |

| Region | Arab States |

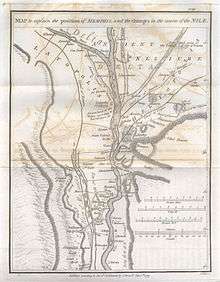

Memphis (Arabic: مَنْف Manf pronounced [mæmf]; Greek: Μέμφις) was the ancient capital of Aneb-Hetch, the first nome of Lower Egypt. Its ruins are located near the town of Mit Rahina, 20 km (12 mi) south of Giza.

According to legend related by Manetho, the city was founded by the pharaoh Menes. Capital of Egypt during the Old Kingdom, it remained an important city throughout ancient Mediterranean history.[2][3][4] It occupied a strategic position at the mouth of the Nile delta, and was home to feverish activity. Its principal port, Peru-nefer, harboured a high density of workshops, factories, and warehouses that distributed food and merchandise throughout the ancient kingdom. During its golden age, Memphis thrived as a regional centre for commerce, trade, and religion.

Memphis was believed to be under the protection of the god Ptah, the patron of craftsmen. Its great temple, Hut-ka-Ptah (meaning "Enclosure of the ka of Ptah"), was one of the most prominent structures in the city. The name of this temple, rendered in Greek as Aί γυ πτoς (Ai-gy-ptos) by the historian Manetho, is believed to be the etymological origin of the modern English name Egypt.

The history of Memphis is closely linked to that of the country itself. Its eventual downfall is believed to be due to the loss of its economic significance in late antiquity, following the rise of coastal Alexandria. Its religious significance also diminished after the abandonment of the ancient religion following the Edict of Thessalonica.

The ruins of the former capital today offer fragmented evidence of its past. They have been preserved, along with the pyramid complex at Giza, as a World Heritage Site since 1979. The site is open to the public as an open-air museum.

Toponymy

| ||||||

| Memphis (mn nfr) in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Memphis has had several names during its history of almost four millennia. Its Ancient Egyptian name was Inbu-Hedj (translated as "the white walls"[5][6]).[7]

Because of its size, the city also came to be known by various other names that were actually the names of neighbourhoods or districts that enjoyed considerable prominence at one time or another. For example, according to a text of the First Intermediate Period,[8] it was known as Djed-Sut ("everlasting places"), which is the name of the pyramid of Teti.[9]

The city was also at one point referred to as Ankh-Tawy (meaning "Life of the Two Lands"), stressing the strategic position of the city between Upper and Lower Egypt. This name appears to date from the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1640 BCE), and is frequently found in ancient Egyptian texts.[10] Some scholars maintain that this name was actually that of the western district of the city that lay between the great Temple of Ptah and the necropolis at Saqqara, an area that contained a sacred tree.[11]

At the beginning of the New Kingdom (c. 1550 BCE), the city became known as Men-nefer (meaning "enduring and beautiful"), which became Menfe in Coptic. The name "Memphis" (Μέμφις) is the Greek adaptation of this name, which was originally the name of the pyramid of Pepi I,[Fnt 1] located west of the city.[12]

In the Bible, Memphis is called Moph or Noph.

Attributes

Location

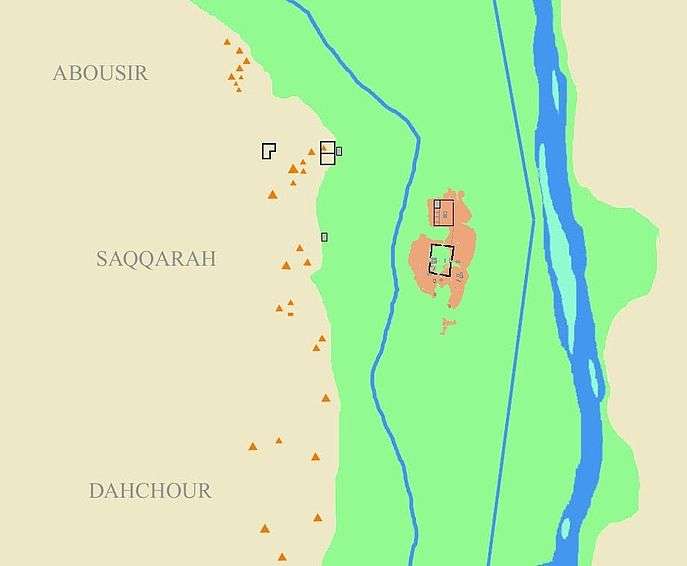

The city of Memphis is 20 km (12 mi) south of Cairo, on the west bank of the Nile. The modern cities and towns of Mit Rahina, Dahshur, Abusir, Abu Gorab, and Zawyet el'Aryan, south of Cairo, all lie within the administrative borders of historical Memphis (29°50′58.8″N 31°15′15.4″E / 29.849667°N 31.254278°E). The city was also the place that marked the boundary between Upper and Lower Egypt. (The 22nd nome of Upper Egypt and 1st nome of Lower Egypt).

Population

The island of the city is today uninhabited. The closest settlement is the town of Mit Rahina. Estimates of historical population size differ widely between sources. According to T. Chandler, Memphis had some 30,000 inhabitants and was by far the largest settlement worldwide from the time of its foundation until around 2250 BCE and from 1557 to 1400 BCE.[13] K. A. Bard is more cautious and estimates the city's population to have amounted to about 6,000 inhabitants during the Old Kingdom.[14]

History

Memphis became the capital of Ancient Egypt for over eight consecutive dynasties during the Old Kingdom. The city reached a peak of prestige under the 6th dynasty as a centre for the worship of Ptah, the god of creation and artworks. The alabaster sphinx that guards the Temple of Ptah serves as a memorial of the city's former power and prestige.[16][17] The Memphis triad, consisting of the creator god Ptah, his consort Sekhmet, and their son Nefertem, formed the main focus of worship in the city.

Memphis declined briefly after the 18th dynasty with the rise of Thebes and the New Kingdom, and was revived under the Persians before falling firmly into second place following the foundation of Alexandria. Under the Roman Empire, Alexandria remained the most important Egyptian city. Memphis remained the second city of Egypt until the establishment of Fustat (or Fostat) in 641 CE. It was then largely abandoned and became a source of stone for the surrounding settlements. It was still an imposing set of ruins in the 12th century but soon became a little more than an expanse of low ruins and scattered stone.

Legendary history

The legend recorded by Manetho was that Menes, the first pharaoh to unite the Two Lands, established his capital on the banks of the Nile by diverting the river with dikes. The Greek historian Herodotus, who tells a similar story, relates that during his visit to the city, the Persians, at that point the suzerains of the country, paid particular attention to the condition of these dams so that the city was saved from the annual flooding.[18] It has been theorised that Menes was possibly a mythical king, similar to Romulus of Rome. Some scholars suggest that Egypt most likely became unified through mutual need, developing cultural ties and trading partnerships, although it is undisputed that the first capital of united Egypt was the city of Memphis.[19] Egyptologists have also identified the legendary Menes with the historical Narmer, who is represented in the Palette of Narmer conquering the Nile delta in Lower Egypt and establishing himself as pharaoh. This palette has been dated to ca. 31st century BC, and would thus correlate with the story of Egypt's unification by Menes. However, in 2012 an inscription depicting the visit of the predynastic king Iry-Hor to Memphis was discovered in the Sinai.[1] Since Iry-Hor predates Narmer by two generations, the latter cannot have been the founder of the city.[1]

Old Kingdom

Little is known about the city of the Old Kingdom. It was the state capital of the godlike pharaohs, who reigned from Memphis from the date of the 1st dynasty. During the earliest years of the reign of Menes, according to Manetho, the seat of power was further to the south, at Thinis.

According to Manetho, ancient sources suggest the "white walls" (Ineb-hedj) were founded by Menes. Referred to in some texts as the "Fortress of the White Wall", it is likely that the king established himself here to better control this new union between the two rival kingdoms. The complex of Djoser of the 3rd dynasty, located in the ancient necropolis at Saqqara, would then be the royal funerary chamber, housing all the elements necessary to royalty: temples, shrines, ceremonial courts, palaces and barracks.

The golden age began with the 4th dynasty, which seems to have furthered the primary role of Memphis as a royal residence where rulers received the double crown, the divine manifestation of the unification of the Two Lands. Coronations and jubilees such as the Sed festival were celebrated in the temple of Ptah. The earliest signs of such ceremonies were found in the chambers of Djoser.

It was also during this period that developed the clergy of the temple of Ptah. The importance of the shrine is attested in this period with payments of food and other goods necessary for the funerary rites of royal and noble dignitaries.[20] This shrine is also cited in the annals preserved on the Palermo Stone, and beginning from the reign of Menkaura, we know the names of the high priests of Memphis that seem to work in pairs at least until the reign of Teti.

The architecture of this period was similar to that seen at Giza, royal necropolis of the Fourth dynasty, where recent excavations have revealed that the essential focus of the kingdom at that time centred on the construction of the royal tomb. A strong suggestion of this notion is the etymology of the name of the city itself, which matched that of the pyramid of Pepi I of the 6th dynasty. Memphis was then the heir to a long artistic and architectural practice, constantly encouraged by the monuments of preceding reigns.

All these necropoleis were surrounded by camps inhabited by craftsmen and labourers, dedicated exclusively to the construction of royal tombs. Spread over several kilometres stretching in all directions, Memphis formed a true megalopolis, with temples connected by sacred temenos, and ports connected by roadways and canals.[21] The perimeter of the city thus gradually extended into a vast urban sprawl. Its centre remained around the temple complex of Ptah.

Middle Kingdom

In the beginning of the Middle Kingdom, the capital and court of the pharaoh had moved to Thebes in the south, leaving Memphis for a time in the shade. Although the seat of political power had been shifted, however, Memphis remained perhaps the most important commercial and artistic centre, as evidenced by the discovery of handicrafts districts and cemeteries, located west of the temple of Ptah.[22]

Also found were vestiges attesting to the architectural focus of this time. A large granite offering table on behalf of Amenemhat I mentioned the erection by the king of a shrine to the god Ptah, master of Truth.[23] Other blocks registered in the name of Amenemhat II were found to be used as foundations for large monoliths preceding the pylons of Rameses II. These kings were also known to have ordered mining expeditions, raids or military campaigns beyond the borders, erecting monuments or statues to the consecration of deities, evinced by a panel recording official acts of the royal court during this time. In the ruins of the Temple of Ptah, a block in the name of Senusret II bears an inscription indicating an architectural commission as a gift to the gods of Memphis.[24] Moreover, many statues found at the site, later restored by the New Kingdom pharaohs, are attributed to pharaohs of the 12th dynasty. Examples include the two stone giants that have been recovered amidst the temple ruins, which were later restored under the name of Rameses II.[25]

Finally, according to the tradition recorded by Herodotus[26] and Diodorus,[27] Amenemhet III built the northern gate of the Temple of Ptah. Remains attributed to this pharaoh were indeed found during the excavations in this area conducted by Flinders Petrie, who confirmed the connection. It is also worth noting that, during this time, mastabas of the high priests of Ptah were constructed near the royal pyramids at Saqqara, showing that the royalty and the clergy of Memphis at that time were closely linked. The 13th dynasty continued this trend, and some pharaohs of this line were buried at Saqqara, attesting that Memphis retained its place at the heart of the monarchy.

With the invasion of the Hyksos, and their rise to power ca. 1650 BC, the city of Memphis came under siege. Following its capture, many monuments and statues of the ancient capital and were dismantled, looted or damaged by the Hyksos kings, who later carried them to adorn their new capital at Avaris.[Fnt 2] Evidence of royal propaganda has been uncovered and attributed to the Theban kings of the 17th dynasty, who initiated the reconquest of the kingdom half a century later.

New Kingdom

The 18th dynasty thus opened with the victory over the invaders by the Thebans. Although the reigns of Amenhotep II (r. 1427–1401/1397 BC) and Thutmose IV (r. 1401/1397–1391/1388 BC) saw considerable royal focus in Memphis, power remained for the most part in the south.[28] With the long period of peace that followed, prosperity again took hold of the city, which benefited from her strategic position. Strengthening trade ties with other empires meant that the port of Peru-nefer (literally means "Bon Voyage") became the gateway to the kingdom for neighbouring regions, including Byblos and the Levant.

In the New Kingdom, Memphis became a centre for the education of royal princes and the sons of the nobility. Amenhotep II, born and raised in Memphis, was made the setem—the high priest over Lower Egypt—during the reign of his father. His son, Thutmose IV received his famed and recorded dream whilst residing as a young prince in Memphis. During his exploration of the site, Karl Richard Lepsius (1810–1884; Prussian Egyptologist and linguist)identified a series of blocks and broken colonnades in the name of Thutmose IV to the east of the Temple of Ptah. They had to belong to a royal building, most likely a ceremonial palace.

The founding of the temple of Astarte (Mespotamian/Assyrian goddess of fertility and war; Babylonian = Ishtar), which Herodotus mistakes as being dedicated to the Greek goddess Aphrodite, may also be dated to the 18th dynasty, specifically the reign of Amenhotep III (r. 1388/86–1351/1349 BC). The greatest work of this pharaoh in Memphis, however, was a temple called "Nebmaatra united with Ptah", which is cited by many sources from the period of his reign, including artefacts listing the works of Huy, the High Steward of Memphis.[29] The location of this temple has not been precisely determined, but a number of its brown quartzite blocks were found to have been reused by Ramesses II (r. 1279–1213 BC) for the construction of the small temple of Ptah. This leads some Egyptologists to suggest that the latter temple had been built over the site of the first.[30]

According to inscriptions found in Memphis, Akhenaten (r. 1353/51–1336/34 BC; formerly Amenhotep IV) founded a temple of Aten in the city.[31] The burial chamber of one of the priests of this cult has been uncovered at Saqqara.[32] His successor Tutankhamun (r. 1332–1323 BC; formerly Tutankhaten) relocated the royal court from Akhenaten's capital Akhetaten ("Horizon of the Aten") to Memphis before the end of the second year of his reign. Whilst in Memphis, Tutankhamun initiated a period of restoration of the temples and traditions following the monotheistic era of Atenism, which was regarded as heresy.

The tombs of important officials from his reign, such as Horemheb and Maya, are situated in Saqqara, although Horemheb was eventually buried in the Valley of the Kings after reigning as pharaoh himself (r. 1319–1292 BC). He had been Commander of the Army under Tutankhamun and Ay. Maya was Overseer of the Treasury during the reigns of Tutankhamun, Ay, and Horemheb. Ay had been Tutankhamun's chief minister, and succeeded him as pharaoh (r. 1323–1319 BC). To consolidate his power he married Tutankhamun's widow Ankhesenamun, the third of the six daughters of Akhenaten and Nefertiti. Her fate is unknown. Horemheb did likewise when he married Nefertiti's sister Mutnodjemet.

There is evidence that, under Ramesses II, the city developed new importance in the political sphere through its proximity to the new capital Pi-Ramesses. The pharaoh devoted many monuments in Memphis and adorned them with colossal symbols of glory. Merneptah (r. 1213–1203 BC), his successor, constructed a palace and developed the southeast wall of the temple of Ptah. For the early part of the 19th dynasty, Memphis received the privileges of royal attention, and it is this dynasty that is most evident among the ruins of the city today.

With the 21st and 22nd dynasties, we see a continuation of the religious development initiated by Ramesses. Memphis does not seem to suffer a decline during the Third Intermediate Period, which saw great changes in the geopolitics of the country. Instead it is likely that the pharaohs worked to develop the Memphite cult in their new capital of Tanis, to the northeast. In light of some remains found at the site, it is known that a temple of Ptah was based there. Siamun is cited as having built a temple dedicated to Amun, the remains of which were found by Flinders Petrie in the early 20th century, in the south of the temple of Ptah complex.[33]

According to inscriptions describing his architectural work, Sheshonk I (r. 943–922 BC), founder of the 22nd dynasty, constructed a forecourt and pylon of the temple of Ptah, a monument which he called the "Castle of Millions of Years of Sheshonk, Beloved of Amun". The funerary cult surrounding this monument, well known in the New Kingdom, was still functioning several generations after its establishment at the temple, leading some scholars to suggest that it may have contained the royal burial chamber of the pharaoh himself.[34] Sheshonk also ordered the building of a new shrine for the god Apis, especially devoted to funeral ceremonies in which the bull was led to his death to be ritually mummified.[35][36]

A necropolis for the high priests of Memphis dating precisely from the 22nd dynasty has been found west of the forum. It included a chapel dedicated to Ptah by a prince Shoshenq, son of Osorkon II (r. 872–837 BC), whose tomb was found in Saqqara in 1939 by Pierre Montet. The chapel is currently visible in the gardens of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, behind a trio of colossi of Ramesses II, which are also from Memphis.

Late Period

During the Third Intermediate Period and the Late Period, Memphis is often the scene of liberation struggles of the local dynasties against an occupying force, such as the Kushites, Assyrians and Persians.

The triumphant campaign of Piankhi, ruler of the Kushites, saw the establishment of the 25th dynasty, whose seat of power was in Napata. Piankhi's conquest of Egypt was recorded on the Victory Stele at the Temple of Amun in Gebel Barkal. Following the capture of Memphis, he restored the temples and cults neglected during the reign of the Libyans. His successors are known for building for chapels in the southwest corner of the temple of Ptah.[37]

Memphis was at the heart of the turmoil produced by the great Assyrian threat. Under Taharqa, the city formed the frontier base of the resistance, which soon crumbled as the Kushite king was driven back into Nubia. The Assyrian king Esarhaddon, supported by some of the native Egyptian princes, captured Memphis in 671 BCE. His forces sacked and raided the city, slaughtered villagers and erected piles of their heads. Esarhaddon returned to his capital Nineveh with rich booty, and erected a victory stele showing the son of Taharqa in chains. Almost as soon as the king left, Egypt rebelled against Assyrian rule.

In Assyria, Ashurbanipal succeeded his father and resumed the offensive against Egypt. In a massive invasion in 664 BCE, the city of Memphis was again sacked and looted, and the king Tantamani was pursued into Nubia and defeated, putting a definitive end to the Kushite reign over Egypt. Power then returned to the Saite pharaohs, who, fearful of an invasion from the Babylonians, reconstructed and even fortified structures in the city, as is attested by the palace built by Apries.

Egypt and Memphis were taken for Persia by king Cambysis in 525 BC after the Battle of Pelusium. Under the Persians, structures in the city were preserved and strengthened, and Memphis was made the administrative headquarters of the newly conquered satrapy. A Persian garrison was permanently installed within the city, probably in the great north wall, near the domineering palace of Apries. The excavations by Flinders Petrie revealed that this sector included armouries. For almost a century and a half, the city remained the capital of the Persian satrapy of Egypt ("Mudraya"/"Musraya"), officially becoming one of the epicentres of commerce in the vast territory conquered by the Achaemenid monarchy.

The steles dedicated to Apis in the Serapeum at Saqqara, commissioned by the reigning monarch, represent a key element in understanding the events of this period. As in the Late Period, the catacombs in which the remains of the sacred bulls were buried gradually grew in size, and later took on a monumental appearance that confirms the growth of the cult's hypostases throughout the country, and particularly in Memphis and its necropolis. Thus, a monument dedicated by Cambyses II seems to refute the testimony of Herodotus, who lends the conquerors a criminal attitude of disrespect against the sacred traditions.

The nationalist awakening came with the rise to power, however briefly, of Amyrtaeus in 404 BCE, who ended the Persian occupation. He was defeated and executed at Memphis in October 399 BCE by Nepherites I, founder of the 29th dynasty. The execution was recorded in an Aramaic papyrus document (Papyrus Brooklyn 13). Nepherites moved the capital to Mendes, in the eastern delta, and Memphis lost its status in the political sphere. It retained, however, its religious, commercial, and strategic importance, and was instrumental in resisting Persian attempts to reconquer Egypt.

Under Nectanebo I, a major rebuilding program was initiated for temples across the country. In Memphis, a powerful new wall was rebuilt for the Temple of Ptah, and developments were made to temples and chapels inside the complex. Nectanebo II meanwhile, while continuing the work of his predecessor, began building large sanctuaries, especially in the necropolis of Saqqara, adorning them with pylons, statues and paved roads lined with rows of sphinxes. Despite his efforts to prevent the recovery of the country by the Persians, he succumbed to a massive invasion in 343 BCE, and was defeated at Pelusium. Nectanebo II retreated south to Memphis, to which the emperor Artaxerxes III laid siege, forcing the pharaoh to flee to Upper Egypt, and eventually to Nubia.

A brief liberation of the city under the rebel-king Khababash (338 to 335 BCE) is evinced by an Apis bull sarcophagus bearing his name, which was discovered at Saqqara dating from his second year. The armies of Darius III eventually regained control of the city.

Memphis under the Late Period saw recurring invasions followed by successive liberations. Several times besieged, it was the scene of several of the bloodiest battles in the history of the country. Despite the support of their Greek allies in undermining the hegemony of the Achaemenids, the country nevertheless fell into the hands of the conquerors, and Memphis was never again to become the nation's capital. In 332 BCE came the Greeks, who took control of the country from the Persians, and Egypt would never see a new native ruler ascend the pharaoh's throne until the Egyptian Revolution of 1952.

Ptolemaic Period

.jpg)

In 332 BCE, Alexander the Great was crowned pharaoh in the Temple of Ptah, ushering in the Hellenistic period. The city retained a significant status, especially religious, throughout the period following the takeover by one of his generals, Ptolemy. On the death of Alexander in Babylon (323 BCE), Ptolemy took great pains in acquiring his body and bringing it to Memphis. Claiming that the king himself had officially expressed a desire to be buried in Egypt, he then carried the body of Alexander to the heart of the temple of Ptah, and had him embalmed by the priests. By custom, kings in Macedon asserted their right to the throne by burying their predecessor. Ptolemy II later transferred the sarcophagus to Alexandria, where a royal tomb was constructed for its burial. The exact location of the tomb has been lost since then. According to Aelian, the seer Aristander foretold that the land where Alexander was laid to rest "would be happy and unvanquishable forever".

Thus began the Ptolemaic dynasty, during which began the city's gradual decline. It was Ptolemy I who first introduced the cult of Serapis in Egypt, establishing his cult in Saqqara. From this period date many developments of the Saqqara Serapeum, including the building of the Chamber of Poets, as well as the dromos adorning the temple, and many elements of Greek-inspired architecture. The cult's reputation extended beyond the borders of the country, but was later eclipsed by the great Alexandrian Serapeum, built in Ptolemy's honour by his successors.

The Decrees of Memphis were issued in 216 and 196 BCE, by Ptolemy IV and Ptolemy V respectively. Delegates from the principal clergies of the kingdom gathered in synod, under the patronage of the High Priest of Ptah and in the presence of the pharaoh, to establish the religious policy of the country for years to come, also dictating fees and taxes, creating new foundations, and paying tribute to the Ptolemaic rulers. These decrees were engraved on stelae in three scripts to be read and understood by all: Demotic, hieroglyphic, and Greek. The most famous of these stelae is the Rosetta Stone, which allowed the deciphering of ancient Egyptian script in the 19th century.

There were other stelae, funerary this time, discovered on the site that have forwarded knowledge of the genealogy of the higher clergy of Memphis, a dynasty of high priests of Ptah. The lineage retained strong ties with the royal family in Alexandria, to the extent that marriages occurred between certain high priests and Ptolemaic princesses, strengthening even further the commitment between the two families.

Decline and abandonment

With the arrival of the Romans, Memphis, like Thebes, lost its place permanently in favour of Alexandria, which opened onto the empire. The rise of the cult of Serapis, a syncretic deity most suited to the mentality of the new rulers of Egypt, and the emergence of Christianity taking root deep into the country, spelled the complete ruin of the ancient cults of Memphis.

Gradually, the city dropped out of existence during the Byzantine and Coptic periods. The city then became a quarry to build new settlements nearby, including a new capital founded by the Arabs who took possession in the 7th century. The foundations of Fustat and later Cairo, both built further north, were laid with stones of dismantled temples and ancient necropoleis of Memphis. In the 13th century, the Arab chronicler Abd-ul-Latif, upon visiting the site, describes and gives testimony to the grandeur of the ruins.

"Enormous as are the extent and antiquity of this city, in spite of the frequent change of governments whose yoke it has borne, and the great pains more than one nation has been at to destroy it, to sweep its last trace from the face of the earth, to carry away the stones and materials of which it was constructed, to mutilate the statues which adorned it; in spite, finally, of all that more than four thousand years have done in addition to man, these ruins still offer to the eye of the beholder a mass of marvels which bewilder the senses and which the most skillful pens must fail to describe. The more deeply we contemplate this city the more our admiration rises, and every fresh glance at the ruins is a fresh source of delight ... The ruins of Memphis hold a half-day's journey in every direction.[38][39]"

Although the remains today are nothing compared to what was witnessed by the Arab historian, his testimony has inspired the work of many archaeologists. The first surveys and excavations of the 19th century, and the extensive work of Flinders Petrie, have been able to show a little of the ancient capital's former glory. Memphis and its necropolis, which include funerary rock tombs, mastabas, temples and pyramids, were inscribed on the World Heritage List of UNESCO in 1979.

Remains

During the time of the New Kingdom, and especially under the reign of the rulers of the 19th dynasty, Memphis flourished in power and size, rivalling Thebes both politically and architecturally. An indicator of this development can be found in a chapel of Seti I dedicated to the worship of Ptah. After over a century of excavations on the site, archaeologists have gradually been able to confirm the layout and expansion of the ancient city.

Great Temple of Ptah

The Hout-ka-Ptah,[Fnt 3] dedicated to the worship of the creator god Ptah, was the largest and most important temple in ancient Memphis. It was one of the most prominent structures in the city, occupying a large precinct within the city's centre. Enriched by centuries of veneration, the temple was one of the three foremost places of worship in Ancient Egypt, the others being the great temples of Ra in Heliopolis, and of Amun in Thebes.

Much of what is known about the ancient temple today comes from the writings of Herodotus, who visited the site at the time of the first Persian invasion, long after the fall of the New Kingdom. Herodotus claimed that the temple had been founded by Menes himself, and that the core building of the complex was restricted to priests and kings.[40] His account, however, gives no physical description of the complex. Archaeological work undertaken in the last century has gradually unearthed the temple's ruins, revealing a huge walled compound accessible by several monumental gates located along the southern, western and eastern walls.

The remains of the great temple and its premises are displayed as an open-air museum near the great colossus of Rameses II, which originally marked the southern axis of the temple. Also in this sector is a large sphinx monolith, discovered in the 19th century. It dates from the 18th dynasty, most likely having been carved during the reign of either Amenhotep II or Thutmose IV. It is one of the finest examples of this kind statuary still present on its original site.

The outdoor museum houses numerous other statues, colossi, sphinxes, and architectural elements. However, the majority of the finds have been sold to major museums around the world. For the most part, these can be found on display in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

The specific appearance of the temple is unclear at present, and only that of the main access to the perimeter are known. Recent developments include the discovery of giant statues which adorned the gates or towers. Those that have been found date from the reign of Ramsses II. This pharaoh also built at least three shrines within the temple compound, where worship is associated with those deities to whom they were dedicated.

Temple of Ptah of Rameses II

This small temple, adjoining the southwest corner of the larger Temple of Ptah, was dedicated to the deified Rameses II, along with the three state gods: Horus, Ptah and Amun. It is known in full as the Temple of Ptah of Rameses, Beloved of Amun, God, Ruler of Heliopolis.[41]

Its ruins were discovered in 1942, by archaeologist Ahmed Badawy, and were excavated in 1955 by Rudolf Anthes. The excavations uncovered a religious building complete with a tower, a courtyard for ritual offerings, a portico with columns followed by a pillared hall and a tripartite sanctuary, all enclosed in walls built of mud bricks. Its most recent exterior has been dated from the New Kingdom era.

The temple opened to the east towards a path paved with other religious buildings. The archaeological explorations that took place here reveal that the southern part of the city indeed contain a large number of religious buildings with a particular devotion to the god Ptah, the principal god of Memphis.

Temple of Ptah and Sekhmet of Rameses II

Located further east, and near to the great colossus of Rameses, this small temple is attributed to the 19th dynasty, and seems to have been dedicated to Ptah and his divine consort Sekhmet, as well as deified Rameses II. Its ruins are not as well preserved as others nearby, as its limestone foundations appear to have been quarried after the abandonment of the city in late antiquity.

Two giant statues, dating from the Middle Kingdom, originally adorned the building's facade, which opened to the west. They were moved inside the Museum of Memphis, and depicted the pharaoh standing in the attitude of the march, wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt, Hedjet.

Temple of Ptah of Merneptah

In the southeast of the Great Temple complex, the pharaoh Merneptah, of the 19th dynasty, founded a new shrine in honour of the chief god of the city, Ptah. This temple was discovered in the early 20th century by Flinders Petrie, who identified a depiction of the Greek god Proteus cited by Herodotus.

The site was excavated during the First World War by Clarence Stanley Fisher. Excavations began in the anterior part, which is formed by a large courtyard of about 15 sq metres, opening on the south by a large door with reliefs supplying the names of the pharaoh and the epithets of Ptah. Only this part of the temple has been unearthed; the remainder of the chamber has yet to be explored a little further north. During the excavations, archaeologists unearthed the first traces of an edifice built of mud brick, which quickly proved to be a large ceremonial palace built alongside the temple proper. Some of the key elements of the stone temple were donated by Egypt to the museum at the University of Pennsylvania, which financed the expedition, while the other remained at the Museum in Cairo.

The temple remained in use throughout the rest of the New Kingdom, as evidenced by enrolment surges during the reigns of later pharaohs. Thereafter, however, it was gradually abandoned and converted for other uses by civilians. Gradually buried by the activity of the city, the stratigraphic study of the site shows that by the Late Period it was already in ruins and is soon covered by new buildings.

Temple of Hathor

This small temple of Hathor was unearthed south of the great wall of the Hout-Ka-Ptah by Abdullah al-Sayed Mahmud in the 1970s and also dates from the time of Rameses II.[42] Dedicated to the goddess Hathor, Lady of the Sycamore, it presents an architecture similar to the small temple-shrines known especially to Karnak. From its proportions, it does not seem to be a major shrine of the goddess, but is currently the only building dedicated to her discovered in the city's ruins.

It is believed that this shrine was primarily used for processional purposes during major religious festivals. A larger temple dedicated to Hathor, indeed one of the foremost shrines of the goddess in the country, is thought to have existed elsewhere in the city, but to date has not been discovered. A depression, similar to that found near the great temple of Ptah, could indicate its location. Archaeologists believe that it could house the remains of an enclosure and a large monument, a theory attested by ancient sources.

Other temples

A temple dedicated to Mithras, dated from the Roman period, has been uncovered in the grounds north of Memphis. The temple of Astarte, described by Herodotus, was located in the area reserved to the Phoenicians during the time when the Greek author visited the city. The temple of the goddess Neith was said to have been located to the north of the temple of Ptah. Neither of the latter two has been discovered to date.

Memphis is believed to have housed a number of other temples dedicated to gods who accompanied Ptah. Some of these sanctuaries are attested by ancient hieroglyphs, but have not yet been found among the ruins of the city. Surveys and excavations are still continuing at nearby Mit Rahina, and will likely add to the knowledge of the planning of the ancient religious city.

Temple of Sekhmet

A temple dedicated to the goddess Sekhmet, consort of Ptah, has not yet been found but is currently certified by Egyptian sources. Archaeologists are still searching for remains.

It may be located within the precinct of the Hout-ka-Ptah, as would seem to suggest several discoveries made among the ruins of the complex in the late 19th century, including a block of stone evoking the "great door" with the epithet of the goddess,[43] and a column bearing an inscription on behalf of Rameses II declaring him "beloved of Sekhmet".[44] It has also been demonstrated through the Great Harris Papyrus, which states that a statue of the goddess was made alongside those of Ptah and their son, the god Nefertem, during the reign of Rameses III, and that it was commissioned for the gods of Memphis at the heart of the great temple.[45][46]

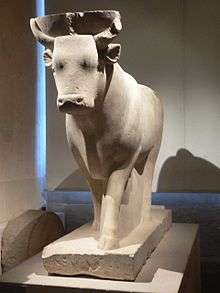

Temple of Apis

The Temple of Apis in Memphis was the main temple dedicated to the worship of the bull Apis, considered to be a living manifestation of Ptah. It is detailed in the works of classical historians such as Herodotus, Diodorus, and Strabo, but its location has yet to be discovered amidst the ruins of the ancient capital.

According to Herodotus, who described the temple's courtyard as a peristyle of columns with giant statues, it was built during the reign of Psammetichus I.

The Greek historian Strabo visited the site with the conquering Roman troops, following the victory against Cleopatra at Actium. He details that the temple consisted of two chambers, one for the bull and the other for his mother, and all was built near the temple of Ptah. At the temple, Apis was used as an oracle, his movements being interpreted as prophecies. His breath was believed to cure disease, and his presence to bless those around with virility. He was given a window in the temple through which he could be seen, and on certain holidays was led through the streets of the city, bedecked with jewellery and flowers.

In 1941, the archaeologist Ahmed Badawy discovered the first remains in Memphis which depicted the god Apis. The site, located within the grounds of the great temple of Ptah, was revealed to be a mortuary chamber designed exclusively for the embalming of the sacred bull. A stele found at Saqqara shows that Nectanebo II had ordered the restoration of this building, and elements dated from the 30th dynasty have been unearthed in the northern part of the chamber, confirming the time of reconstruction in this part of the temple. It is likely that the mortuary was part of the larger temple of Apis cited by ancient sources. This sacred part of the temple would be the only part that has survived, and would confirm the words of Strabo and Diodorus, both of whom stated that the temple was located near the temple of Ptah.[47]

The majority of known Apis statues come from the burial chambers known as Serapeum, located to the northwest at Saqqara. The most ancient burials found at this site date back to the reign of Amenhotep III.

Temple of Amun

During the 21st dynasty, a shrine of the great god Amun was built by Siamun to the south of the temple of Ptah. This temple (or temples) was most likely dedicated to the Theban Triad, consisting of Amun, his consort Mut, and their son Khonsu. It was the Upper Egyptian counterpart of the Memphis Triad (Ptah, Sekhmet, and Nefertem).

Temple of Aten

A temple dedicated to Aten in Memphis is attested by hieroglyphs found within the tombs of Memphite dignitaries of the end of the 18th dynasty, uncovered at Saqqara. Among them, that of Tutankhamun, who began his career under the reign of Akhenaten as a "steward of the temple of Aten in Memphis".

Since the early excavations at Memphis in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, artefacts have been uncovered in different parts of the city that indicate the presence of a building dedicated to the worship of the sun disc. The location of such a building is lost, and various hypotheses have been made on this subject based on the place of discovery of the remains of the Amarna period features.

Statues of Rameses II

.jpg)

The ruins of ancient Memphis have yielded a large number of sculptures representing Pharaoh Rameses II.

Within the museum in Memphis is a giant statue of the pharaoh carved of monumental limestone, about 10 metres in length. It was discovered in 1820 near the southern gate of the temple of Ptah by Italian archaeologist Giovanni Caviglia. Because the base and feet of the sculpture are broken off from the rest of the body, it is currently displayed lying on its back. Some of the colours are still partially preserved, but the beauty of this statue lies in its flawless detail of the complex and subtle forms of human anatomy. The pharaoh wears the white crown of Upper Egypt, Hedjet.

Caviglia offered to send the statue to Grand Duke of Tuscany, Leopold II, through the mediation of Ippolito Rosellini. Rosellini advised the sovereign of the terrible expenses involved with transportation, and considered as necessary the cutting of the colossus into pieces. The Wāli and self-declared Khedive of Egypt and Sudan, Muhammad Ali Pasha, offered to donate it to the British Museum, but the museum declined the offer because of the difficult task of shipping the huge statue to London. It therefore remained in the archaeological area of Memphis in the museum built to protect it.

The colossus was one of a pair that historically adorned the eastern entrance to the temple of Ptah. The other, found in the same year also by Caviglia, was restored in the 1950s to its full standing height of 11 metres. It was first displayed in the Bab Al-Hadid square in Cairo, which was subsequently renamed Ramses Square. Deemed an unsuitable location, it was moved in 2006 to a temporary location in Giza, where it is currently undergoing restoration. It is due to be exhibited at the entrance of the Grand Egyptian Museum, scheduled to open in 2018. A replica of the statues stands in Cairo's suburb of Heliopolis.

Saqqara, the Necropolis

Because of its antiquity and its large population, Memphis had several necropoleis spread along the valley, including the most famous, Saqqara. In addition, the urban area itself consisted of cemeteries that were constructed to the west of the great temple. The sanctity of these places inevitably attracted the devout and the faithful, who sought either to make an offering to Osiris, or to bury another.

The part of town called Ankh-tawy was already included in the Middle Kingdom necropolis. Expansions of the western sector of the temple of Ptah were ordered by the pharaohs of the 22nd dynasty, seeking to revive the past glory of the Ramesside age. Within this part of the site was founded a necropolis of the high priests.

According to sources, the site also included a chapel or an oratory to the goddess Bastet, which seems consistent with the presence of monuments of rulers of the dynasty following the cult of Bubastis. Also in this area were the mortuary temples devoted by various New Kingdom pharaohs, whose function is parallelled by Egyptologists to that played by the Temples of a Million years of the Theban pharaohs.

Royal palaces

Memphis was the seat of power for the pharaohs of over eight dynasties. According to Manetho, the first royal palace was founded by Hor-Aha, the successor of Narmer, the founder of the 1st dynasty. He built a fortress in Memphis of white walls. Egyptian sources themselves tell of the palaces of the Old Kingdom rulers, some of which were built underneath major royal pyramids. They were immense in size, and were embellished with parks and lakes.[48] In addition to the palaces described below, other sources indicate the existence of a palace founded in the city by Thutmose I, which was still operating under the reign of Tuthmosis IV.

Merneptah, according to official texts of his reign, ordered the building of a large walled enclosure housing a new temple and adjoining palace.[49] The later pharaoh, Apries, had a palatial complex constructed on a promontory overlooking the city. It was part of a series of structures built within the temple precinct in the Late Period, and contained a royal palace, a fortress, barracks and armouries. Flinders Petrie excavated the area and found considerable signs of military activity.[50]

Other buildings

The centrally located palaces and temples were surrounded by different districts of the city, in which were many craftsmen's workshops, arsenals, and dockyards. Also were residential neighbourhoods, some of which were inhabited primarily by foreigners—first Hittites and Phoenicians, later Persians, and finally Greek. The city was indeed located at the crossroads of trade routes and thus attracted goods imported from diverse regions of the Mediterranean.

Ancient texts confirm that citywide development took place regularly. Furthermore, there is evidence that the Nile has shifted over the centuries to the east, leaving new lands to occupy in the eastern part of the old capital.[51] This area of the city was dominated by the large eastern gate of the temple of Ptah.

Historical accounts and exploration

The site of Memphis has been famous since ancient times, and is cited in many ancient sources, including both Egyptian and foreign. Diplomatic records found on different sites have detailed the correspondence between the city and the various contemporary empires in the Mediterranean, Near East, and Africa. These include for example the Amarna letters, which detail trade conducted between Memphis and the sovereigns of Babylon and the various city-states of Lebanon. The proclamations of the later Assyrian kings cite Memphis among its list of conquests.

Sources from antiquity

Beginning with the second half of the 1st millennium BCE, the city was detailed more and more intensely in the words of ancient historians, especially with the development of trade ties with Greece. The descriptions of the city by travellers who followed the traders in the discovery of Egypt have proved instrumental in reconstructing an image of the ancient capital's glorious past. Among the main classical authors are:

- Herodotus, Greek historian, who visited and described the monuments of the city during the first Persian Achaemenid rule in the 5th century BCE.[52]

- Diodorus Siculus, Greek historian, who visited the site in the 1st century BCE, providing later information about the city during the reign of the Ptolemies.[53]

- Strabo, the Hellenistic geographer, who visited during the Roman conquest in the late 1st century BCE.[54]

Subsequently, the city is often cited by other Latin or Greek authors, in rare cases providing an overall description of the city or detailing its cults, as do Suetonius[55] and Ammianus Marcellinus,[56] who pay particular attention to the city's worship of Apis. The city was plunged into oblivion during the Christian period that followed, and few sources are available to attest to the city's activities during its final stages.

It was not until the conquest of the country by the Arabs that a description of the city reappears, by which time it was already in ruins. Among the major sources from this time:

- Abd-al-Latif, a famous geographer of Baghdad, which in the 13th century gives a description of the ruins of the site during his trip to Egypt.

- Al-Maqrizi, Egyptian historian in the 14th century, who visited the site and describes it in detail.

Early exploration

In 1652, Jean de Thévenot, during his trip to Egypt, identified the location of the site and its ruins, confirming the accounts of the old Arab authors for Europe. His description is brief, but represents the first step towards the exploration that will emerge after the development of archaeology.[57] The starting point of archaeological exploration in Memphis was Napoléon Bonaparte's great foray into Egypt in 1798. Research and surveys of the site confirmed the identification of Thévenot, and the first studies of its remains are carried out by scientists accompanying French soldiers. The results of the first scientific studies were published in the monumental Description de l'Égypte, a map of the region, the first to give the location of Memphis with precision.

Nineteenth century

The early French expeditions paved the way for explorations of a deeper scope that would follow from the 19th century until today, conducted by leading explorers, Egyptologists and major archaeological institutions. Here is a partial list:

- The first excavations of the site were made by Caviglia and Sloane in 1820. They discovered the great colossus of Rameses II lying, currently on display in the museum.

- Jean-François Champollion, in his trip to Egypt from 1828 to 1830 through Memphis, described the giant discovered by Caviglia and Sloane, made a few digs at the site and decrypted many of the epigraphic remains. He promised to return with more resources and more time to study, but his sudden death in 1832 meant he did not achieve this ambition.[58]

- Karl Richard Lepsius, during the Prussian expedition of 1842, made a quick survey of the ruins and created a first detailed map that would serve as the basis for all future explorations and excavations.[59]

During the British era in Egypt, the development of agricultural technology along with the systematic cultivation of the Nile floodplains led to a considerable amount of accidental archaeological discoveries. Much of what was found would fall into the hands of major European collectors travelling the country on behalf of the great museums of London, Paris, Berlin, and Turin. It was during one of these land cultivations that peasants discovered, accidentally in 1847 near the village of Mit Rahina, elements of a Roman temple of Mithras.

From 1852 to 1854, Joseph Hekekyan, then working for the Egyptian government, conducted geological surveys on the site, and on these occasions made a number of discoveries, such as those at Kom el-Khanzir (northeast of the great temple of Ptah). These stones decorated with reliefs from the Amarna period, originally from the ancient temple of Aten in Memphis, had almost certainly been reused in the foundations of another ruined monument. He also discovered the great colossus of Rameses II in pink granite.

This spate of archaeological discoveries gave birth to the constant risk of seeing all these cultural riches finally leave Egyptian soil. Auguste-Édouard Mariette, who visited Saqqara in 1850, became aware of the need to create an institution in Egypt responsible for the exploration and conservation of the country's archaeological treasures. He established the Egyptian Antiquities Organisation (EAO) in 1859, and organised excavations at Memphis which revealed the first evidence of the great temple of Ptah, and uncovered the royal statues of the Old Kingdom.[60]

Twentieth century

The major excavations of the British Egyptologist Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, conducted from 1907 to 1912, uncovered the majority of the ruins as seen today. Major discoveries on the site during these excavations included the pillared hall of the temple of Ptah, the pylon of Rameses II, the great alabaster sphinx, and the great wall north of the palace of Apries. He also discovered the remains of the Temple of Amun of Siamon, and the Temple of Ptah of Merneptah.[61] His work was interrupted during the First World War, and would later be taken up by other archaeologists, gradually uncovering some of the forgotten monuments of the ancient capital.

A timeline listing the main findings:

- 1914 to 1921: the excavations of the University of Pennsylvania of the Temple of Ptah of Merneptah, which yield the discovery of the adjoining palace.

- 1942: the EAO survey, led by Egyptologist Ahmed Badawy, discovers the small Temple of Ptah of Rameses, and the chapel of the tomb of prince Shoshenq of the 22nd dynasty.[62]

- 1950: Egyptologist Labib Habachi discovers the chapel of Seti I, on behalf of the Egyptian Antiquities Organisation. The Egyptian government decides to transfer the pink granite colossus of Rameses II to Cairo. It is placed before the city's main train station, in a square subsequently named Midân Rameses.

- 1954: the chance discovery by roadworkers of a necropolis of the Middle Kingdom at Kom el-Fakhri.[63]

- 1955 to 1957: Rudolph Anthes, on behalf of the University of Philadelphia, searches and clears the small Temple of Ptah of Rameses, and the embalming chapel of Apis.[64]

- 1969: the accidental discovery of a chapel of the small Temple of Hathor.[42]

- 1970 to 1984: excavations conducted by the EAO clear the small temple of Hathor; directed by Abdullah el-Sayed Mahmud, Huleil Ghali and Karim Abu Shanab.

- 1980: excavations of the embalming chamber of Apis, and further studies by the American Research Center in Egypt.[65]

- 1982: Egyptologist Jaromir Málek studies and records the findings of the small temple of Ptah of Rameses.[66]

- 1970, and 1984 to 1990: excavations by the Egypt Exploration Society in London. Further excavations of the pillared hall and pylon of Rameses II; the discovery of granite blocks bearing the annals of the reign of Amenemhat II; excavations of the tombs of high priests of Ptah; research and major explorations at the necropolis near Saqqara.[67]

- 2003: renewed excavations of the small temple of Hathor by the EAO (now the Supreme Council of Antiquities).

- 2003 to 2004: Excavations by a combined Russian-Belgian mission in the great wall north of Memphis.

Gallery

Museum worker in the process of cleaning the Rameses II colossus.

Museum worker in the process of cleaning the Rameses II colossus. Depiction of Ptah found on the walls of the Temple of Hathor.

Depiction of Ptah found on the walls of the Temple of Hathor.- The alabaster sphinx found outside the Temple of Ptah.

- Statue of Rameses II in the open-air museum.

.jpg) Closeup of the sphinx outside the Temple of Ptah.

Closeup of the sphinx outside the Temple of Ptah. Colossus of Rameses II.

Colossus of Rameses II.

See also

- Ancient Egypt

- Egyptian pyramids

- List of Egypt-related topics

- Memphis, Tennessee

- Saqqara

- Thebes, Egypt

Notes

- ↑

![Q3 [p] p](../I/m/hiero_Q3.png%3F42130.svg)

![Q3 [p] p](../I/m/hiero_Q3.png%3F42130.svg)

![M17 [i] i](../I/m/hiero_M17.png%3F2e70b.svg)

![M17 [i] i](../I/m/hiero_M17.png%3F2e70b.svg)

Ppj-mn-nfr = Pepi-men-nefer ("Pepi is perfection", or "Pepi is beauty"). - ↑ Most of these relics would be subsequently recovered by Rameses II in order to decorate his new capital at Pi-Rameses. They were later moved again during the Third Intermediate Period to Tanis, and many have been found scattered among the ruins of the country's various ancient capitals.

- ↑

ḥw.t-k3-Ptḥ = Hout-ka-Ptah

References

- 1 2 3 P. Tallet, D. Laisnay: Iry-Hor et Narmer au Sud-Sinaï (Ouadi 'Ameyra), un complément à la chronologie des expéditios minière égyptiene, in: BIFAO 112 (2012), 381–395, available online

- ↑ Bard, Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, p. 694.

- ↑ Meskell, Lynn (2002). Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt. Princeton University Press, p.34

- ↑ Shaw, Ian (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, p.279

- ↑ M. T. Dimick retrieved 14:19GMT 1.10.11

- ↑ Etymology website-www.behindthename.com retrieved 14:22GMT 1.10.11

- ↑ National Geographic Society: Egypt's Nile Valley Supplement Map, produced by the Cartographic Division.

- ↑ Hieratic Papyrus 1116A, of the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg; cf Scharff, Der historische Abschnitt der Lehre für König Merikarê, p.36

- ↑ Montet, Géographie de l'Égypte ancienne, (Vol I), p. 28–29.

- ↑ Najovits, Simson R. Egypt, trunk of the tree: a modern survey of an ancient land (Vol. 1–2), Algora Publishing, p171.

- ↑ Montet, Géographie de l'Égypte ancienne, (Vol I), p. 32.

- ↑ McDermott, Bridget (2001). Decoding Egyptian Hieroglyphs: How to Read the Secret Language of the Pharaohs. Chronicle Books , p.130

- ↑ Chandler, Tertius ( thertgreg1987). Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth.

- ↑ Bard, Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, p. 250

- ↑ "Nefertem". The Walters Art Museum.

- ↑ National Geographic Society: Egypt's Nile Valley Supplement Map. (Produced by the Cartographic Division)

- ↑ Roberts, David (1995). National Geographic: Egypt's Old Kingdom, Vol. 187, Issue 1.

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories (Vol II), § 99

- ↑ Manley, Bill (1997). The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Egypt. Penguin Books.

- ↑ Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, p. 109–110.

- ↑ Goyon, Les ports des Pyramides et le Grand Canal de Memphis, p. 137–153.

- ↑ Al-Hitta, Excavations at Memphis of Kom el-Fakhri, p. 50–51.

- ↑ Mariette, Monuments divers Collected in Egypt and in Nubia, p. 9 and plate 34A.

- ↑ Mariette, Monuments divers Collected in Egypt and in Nubia, § Temple of Ptah, excavations 1871, 1872 and 1875, p. 7 and plate 27A.

- ↑ Brugsch, Collection of Egyptian monuments, Part I, p. 4 and Plate II. This statue is now on display at the Egyptian Museum in Berlin.

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories (Vol II), § 101.

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica, (Vol I), Ch. 2, § 8.

- ↑ Cabrol, Amenhotep III le magnifique, Part II, Ch. 1, p. 210–214.

- ↑ Petrie, Memphis and Maydum III, p. 39.

- ↑ Cabrol, Amenhotep III le magnifique, Part II, Ch. 1.

- ↑ Mariette, Monuments divers collected in Egypt and in Nubia, p. 7 & 10, and plates 27 (fig. E) & 35 (fig. E1, E2, E3).

- ↑ Löhr, Aḫanjāti in Memphis, p. 139–187.

- ↑ Petrie, Memphis I, Ch. VI, § 38, p. 12; plates 30 & 31.

- ↑ Sagrillo, Mummy of Shoshenq I Re-discovered?, p. 95–103.

- ↑ Petrie, Memphis I, § 38, p. 13.

- ↑ Maystre, The High Priests of Ptah of Memphis, Ch. XVI, § 166, p. 357.

- ↑ Meeks, Hommage à Serge Sauneron I, p. 221–259.

- ↑ Joanne & Isambert, Itinéraire descriptif, historique et archéologique de l'Orient, p. 1009.

- ↑ Maspero, Histoire ancienne des peuples de l'Orient, Ch. I, § Origine des Égyptiens.

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories (Vol II), § 99.

- ↑ Anthes, Mit Rahineh, p. 66.

- 1 2 Mahmud, A new temple for Hathor at Memphis.

- ↑ Brugsch, Collection of Egyptian monuments, p. 6 and plate IV, 1.

- ↑ Brugsch, Collection of Egyptian monuments, p. 8 and plate IV, 5.

- ↑ Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, § 320 p. 166

- ↑ Grandet, Le papyrus Harris I, § 47,6 p. 287.

- ↑ Jones, The temple of Apis in Memphis, p. 145–147.

- ↑ Lalouette, Textes sacrés et textes profanes de l'Ancienne Égypte (Vol II), p. 175–177.

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories (Vol II), § 112.

- ↑ Petrie, The Palace of Apries (Memphis II), § II, p. 5–7 & plates III to IX.

- ↑ Jeffreys, D.G.; Smith, H.S (1988). The eastward shift of the Nile's course through history at Memphis, p. 58–59.

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories (Vol II), paragraphs 99, 101, 108, 110, 112, 121, 136, 153 and 176.

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica (Vol I), Ch. I, paragraphs 12, 15 and 24; Ch. II, paragraphs 7, 8, 10, 20 and 32.f

- ↑ Strabo, Geographica, Book XVII, chapters 31 and 32.

- ↑ Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Part XI: Life of Titus.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History, Book XXII, § XIV.

- ↑ Thévenot, Relation d’un voyage fait au Levant, Book II, Ch. IV, p. 403; and Ch. VI, p. 429.

- ↑ Champollion-Figeac, l'Égypte Ancienne, p. 63.

- ↑ Lepsius, Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien, booklets of 14 February, 19 February, 19 March and 18 May 1843, p. 202–204; and plates 9 and 10.

- ↑ Mariette, Monuments divers collected in Egypt and in Nubia.

- ↑ Petrie, Memphis I and Memphis II.

- ↑ Badawy, Grab des Kronprinzen Scheschonk, Sohnes Osorkon's II, und Hohenpriesters von Memphis, p. 153–177.

- ↑ El-Hitta, Excavations at Memphis of Kom el-Fakhri.

- ↑ Anthes, works from 1956, 1957 and 1959.

- ↑ Jones, The temple of Apis in Memphis.

- ↑ Málek, A Temple with a Noble Pylon, 1988.

- ↑ Jeffreys, The survey of Memphis, 1985.

Further reading

- Herodotus, The Histories (Vol II).

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica, (Vol I).

- Strabo, Geographica, Book XVII: North Africa.

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Part XI: Life of Titus.

- Ammianus Marcellinus; translation by C.D. Yonge (1862). Roman History, Book XXII. London: Bohn. pp. 276–316.

- Jean de Thévenot (1665). Relation d’un voyage fait au Levant. Paris: L. Billaine.

- Government of France (1809–1822). Description de l'Égypte. Paris: Imprimerie impériale.

- Champollion, Jean-François (1814). L'Égypte sous les Pharaons. Paris: De Bure.

- Champollion, Jacques-Joseph (1840). L'Égypte Ancienne. Paris: Firmin Didot Frères.

- Lepsius, Karl Richard (1849–1859). Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien. Berlin: Nicolaische Buchhandlung.

- Ramée, Daniel (1860). Histoire générale de l'architecture. Paris: Amyot.

- Joanne, Adolphe Laurent; Isambert, Émile (1861). Itinéraire descriptif, historique et archéologique de l'Orient. Paris: Hachette.

- Brugsch, Heinrich Karl (1862). Collection of Egyptian monuments, Part I. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs.

- Mariette, Auguste (1872). Monuments divers collected in Egypt and in Nubia. Paris: A. Franck.

- Maspero, Gaston (1875). Histoire des peuples de l'Orient. Paris: Hachette.

- Maspero, Gaston (1902). Visitor's Guide to the Cairo Museum. Cairo: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale.

- Jacques de Rougé (1891). Géographie ancienne de la Basse-Égypte. Paris: J. Rothschild.

- Breasted, James Henry (1906–1907). Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-8160-4036-2.

- Petrie, W.M. Flinders, Sir (1908). Memphis I. British School of Archaeology; Egyptian Research Account.

- Petrie, W.M. Flinders, Sir (1908). Memphis II. British School of Archaeology; Egyptian Research Account.

- Petrie, W.M. Flinders, Sir (1910). Maydum and Memphis III. British School of Archaeology; Egyptian Research Account.

- Al-Hitta, Abdul Tawab (1955). Excavations at Memphis of Kom el-Fakhri. Cairo.

- Anthes, Rudolf (1956). A First Season of Excavating in Memphis. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia.

- Anthes, Rudolf (1957). Memphis (Mit Rahineh) in 1956. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia.

- Anthes, Rudolf (1959). Mit Rahineh in 1955. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia.

- Badawy, Ahmed (1956). Das Grab des Kronprinzen Scheschonk, Sohnes Osorkon's II, und Hohenpriesters von Memphis. Cairo: Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte, Issue 54.

- Montet, Pierre (1957). Géographie de l'Égypte ancienne, (Vol I). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.

- Goyon, Georges (1971). Les ports des Pyramides et le Grand Canal de Memphis. Paris: Revue d'Égyptologie, Issue 23.

- Löhr, Beatrix (1975). Aḫanjāti in Memphis. Karlsruhe.

- Mahmud, Abdullah el-Sayed (1978). A new temple for Hathor at Memphis. Cairo: Egyptology Today, Issue 1.

- Meeks, Dimitri (1979). Hommage à Serge Sauneron I. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Crawford, D.J.; Quaegebeur, J.; Clarysse, W. (1980). Studies on Ptolemaic Memphis. Leuven: Studia Hellenistica.

- Lalouette, Claire (1984). Textes sacrés et textes profanes de l'Ancienne Égypte, (Vol II). Paris: Gallimard.

- Jeffreys, David G. (1985). The Survey of Memphis. London: Journal of Egyptian Archaeology.

- Tanis: l'Or des pharaons. Paris: Association Française d’Action Artistique (1987).

- Thompson, Dorothy (1988). Memphis under the Ptolemies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Málek, Jaromir (1988). A Temple with a Noble Pylon. Archaeology Today.

- Baines, John; Málek, Jaromir (1980). Cultural Atlas of Ancient Egypt. Oxfordshire: Andromeda. ISBN 0-87196-334-5.

- Alain-Pierre, Zivie (1988). Memphis et ses nécropoles au Nouvel Empire. Paris: French National Centre for Scientific Research.

- Sourouzian, Hourig (1989). Les monuments du roi Mérenptah. Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philpp von Zabern.

- Jones, Michael (1990). The temple of Apis in Memphis. London: Journal of Egyptian Archaeology (Vol 76).

- Martin, Geoffrey T. (1991). The Hidden Tombs of Memphis. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Maystre, Charles (1992). The High Priests of Ptah of Memphis. Freiburg: Universitätsverlag.

- Cabrol, Agnès (2000). Amenhotep III le magnifique. Rocher: Editions du Rocher.

- Hawass, Zahi; Verner, Miroslav (2003). The Treasure of the Pyramids. Vercelli.

- Grandet, Pierre (2005). Le papyrus Harris I (BM 9999). Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Sagrillo, Troy (2005). The Mummy of Shoshenq I Re-discovered?. Göttingen: Göttinger Miszellen, Issue 205. pp. 95–103.

- Bard, Katheryn A. (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Memphis. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- On the Memphis Theology

- Ancient Egypt.org

- Photos of Memphis, University of Chicago

- Digital Egypt for Universities

- Photos of Memphis, Egiptomania.com

| Preceded by Thinis |

Capital of Egypt 3100–2180 BC |

Succeeded by Herakleopolis |