Morganucodonta

| Morganucodonta Temporal range: Late Triassic – Lower Cretaceous 210–140 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Life restoration of a Megazostrodon, Natural History Museum, London | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Order: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | Cynodontia |

| Clade: | Mammaliaformes |

| Clade: | †Morganucodonta Kermack, Mussett & Rigney, 1973 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Morganucodonta ("Glamorgan teeth") is an extinct order of basal mammaliaformes, the precursors to crown-group mammals (Mammalia). Their remains have been found in southern Africa, Western Europe, North America, India and China. The morganucodontans were probably insectivorous and nocturnal. Nocturnality is believed to have evolved in the earliest mammals in the Triassic (called the nocturnal bottleneck) as a specialisation that allowed them to exploit a safer, night-time niche, while most larger predators were likely to have been active during the day (though some dinosaurs for example were nocturnal as well[1]).

Anatomy and biology

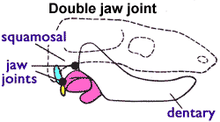

Morganucodontans had a double jaw articulation made up of the dentary-squamosal joint as well as a quadrate-articular one. They also retained their postdentary bones: the articular and quadrate. There is a trough at the back of the jaw on the inside (lingual) where the postdentary bones sat. The double jaw articulation and retention of the postdentary bones are characteristic of many of the earliest mammals, but are absent today in mammals: all crown-group mammals by definition have a jaw that is composed of a single bone, and the articular and quadrate bones have been incorporated into the middle ear, having become the malleus and incus respectively.

Unlike Sinoconodon and other therapsids, morganucodontan teeth were diphyodont (meaning that they replaced their teeth once, having a 'milk' set and 'adult' set as seen in today's mammals including humans[2] and not polyphyodont (meaning that the teeth are constantly replaced, and the animal and its teeth get larger throughout its lifetime, as in reptiles). Evidence of lactation is present in Wareolestes, via tooth replacement patterns.[3]

Morganucodontans also had specialised teeth – incisors, canines, molars and premolars – for food processing, rather than having similarly shaped teeth along the tooth row as seen in their predecessors. Morganucododontans are thought to have been insectivorous and carnivorous, their teeth adapted for shearing. Niche partitioning is known among various morganucodontan species, different types specialised for different prey.[4]

The teeth are structured in such a way that occlusion happens by the lower cusp "a" fitting anteriorly to upper cusp "A", between "A" and "B". This occlusion pattern is also seen in the unrelated triconodontids, but it is by no means universal among morganucodontans; Dinnetherium, for example has an occlusion mechanism closer to that of gobiconodontids (also unrelated), in which molars basically alternate.[5] Wear facets are present.

The septomaxilla, a primitive feature also found in Sinoconodon, is found in morganucodontans, as well as a fully ossified orbitosphenoid. The anterior lamina is enlarged. The cranial moiety of the squamosal is a narrow bone that is superficially placed to the petrosal and parietal. Unlike its predecessors, the morganucodontans have a larger cerebral capacity and a longer cochlea.

The atlas elements are unfused; there is a suture between the dens and axis. The cervical ribs are not fused to the centra. The coracoid and procoracoid, which are absent in therians, are present. The head of the humerus is spherical as in mammals, but the spiral ulnar condyle is cynodont-like. In the pelvic girdle, the pubis, ilium and ischium are unfused. At least Megazostrodon and Erythrotherium are unique among mammaliformes for lacking epipubic bones, suggesting that they didn't have the same reproductive constraints.[6]

Classification

Because morganucodontans possessed the mammalian dentary-squamosal jaw joint, systematists like G. G. Simpson (1959)[7] considered the morganucodontans to be mammals. Some palaeontologists continue to use this classification.[8] Others use crown-group terminology, which limits Mammalia to the animals that had a single jaw joint (not double as in morganucodontans) and other specific mammalian skeletal characteristics. By this definition, more basal orders like morganucodontans are not in Mammalia, but are mammaliaformes.[9] This is the most commonly accepted classification system.

†Morganucodonta Kermack, Mussett & Rigney 1973 sensu Kielan-Jaworowska, Cifelli & Luo 2004[10][11]

- †Bridetherium dorisae Clemens 2011

- †Hallautherium schalchi Clemens 1980

- †Paceyodon davidi Clemens 2011

- †Purbeckodon batei Butler, Sigogneau-Russell & Ensom 2012

- †Rosierodon anceps Debuysschere, Gherrbrant & Allain 2014

- †Morganucodontidae Kühne 1958

- †Gondwanadon tapani Datta & Das 1996

- †Holwellconodon problematicus Lucas & Hunt 1990

Yadagiri 1984 non Kretzoi 1942; Indotherium pranhitai Yadagiri 1984]

- †Likhoeletherium Ellenberger 1970 (nomen nudum)

- †Helvetiodon schuetzi Clemens 1980 [Helveticodon Tatarinov 1985]

- †Erythrotherium parringtoni Crompton 1964

- †Eozostrodon parvus Parrington 1941 [Eozostrodon problematicus Parrington 1941; Morganucodon parvus (Parrington 1941)]

- †Morganucodon Kühne 1949

- †M. watsoni Kühne 1949 [Eozostrodon watsoni (Kühne 1949)]

- †M. oehleri Rigney 1963 [Eozostrodon oehleri (Rigney 1963)]

- †M. heikuopengensis (Young 1978) [Eozostrodon heikuopengensis Young 1978]

- †M. peyeri Clemens 1980 Eozostrodon peyeri (Clemens 1980)]

- †Megazostrodontidae Cow 1986 sensu Kielan-Jaworowska, Cifelli & Luo 2004

- †Wareolestes rex Freeman 1979

- †Brachyzostrodon Sigogneau-Russell 1983a

- †B. coupatezi Sigogneau-Russell 1983a

- †B. molar Hahn, Sigogneau-Russell & Godefroit 1991

- †Megazostrodon Crompton & Jenkins 1968

- †M. rudnerae Crompton & Jenkins 1968

- †M. chenali Debuysschere, Gherrbrant & Allain 2014

- †Indozostrodon simpsoni Datta & Das 2001 sensu Prasad & Manhas 2002 [Indotherium

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ Schmitz, Lars; Motani, Ryosuke (2011). "Nocturnality in dinosaurs inferred from scleral ring and orbit morphology". Science. 332: 705–708. PMID 21493820. doi:10.1126/science.1200043.

- ↑ Panciroli E. 2017 Fossil Focus: The First Mammals - http://www.palaeontologyonline.com/articles/2017/fossil-focus-first-mammals/)

- ↑ Elsa Panciroli; Roger B. J. Benson; Stig Walsh (2017). "The dentary of Wareolestes rex (Megazostrodontidae): a new specimen from Scotland and implications for morganucodontan tooth replacement". Papers in Palaeontology. in press. doi:10.1002/spp2.1079.

- ↑ Gill, Pamela G.; Purnell, Mark A.; Crumpton, Nick; Brown, Kate Robson; Gostling, Neil J.; Stampanoni, M.; Rayfield, Emily J. (21 August 2014). "Dietary specializations and diversity in feeding ecology of the earliest stem mammals". Nature. 512 (7514): 303–305. doi:10.1038/nature13622. Retrieved 12 July 2017 – via www.Nature.com.

- ↑ Percy M. Butler; Denise Sigogneau-Russell (2016). "Diversity of triconodonts in the Middle Jurassic of Great Britain" (PDF). Palaeontologia Polonica 67: 35–65. doi:10.4202/pp.2016.67_035.

- ↑ Jason A. Lillegraven, Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska, William A. Clemens, Mesozoic Mammals: The First Two-Thirds of Mammalian History, University of California Press, 17 December 1979 - 321

- ↑ Simpson, George Gayord (1959). "Mesozoic mammals and the polyphyletic origin of mammals" (PDF). Evolution. 13 (3): 405–414. doi:10.2307/2406116.

- ↑ Kemp, T. S. (2005). The Origin and Evolution of Mammals. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0198507607.

- ↑ Rowe, T. (1988). "Definition, diagnosis, and origin of Mammalia" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 8 (3): 241–264. doi:10.1080/02724634.1988.10011708.

- ↑ Mikko's Phylogeny Archive Haaramo, Mikko (2007). "Mammaliaformes – mammals and near-mammals". Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Paleofile.com (net, info) . "Taxonomic lists- Mammals". Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- Bibliography

- Rich, PV; Fenton, MA; Fenton, CL; THV, Rich. The Fossil Book: A Record of Prehistoric Life. p. 519. ISBN 9780486293714.

- Palmer, D, ed. (2006). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Prehistoric World. Book Sales. p. 342. ISBN 9780785820864.

- Kielan-Jaworowska, Z; Luo, ZX; Cifelli, RL (2004). Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs. Columbia University Press. pp. 168–183. ISBN 9780231119184.

External links

- "Mesozoic Mammals; Basal Mammaliaformes, Morganucodontidae, Megazostrodontidae and Hadrocodium, an internet directory". Karin and Trevor Dykes. Retrieved January 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)