Brewery

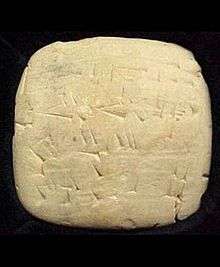

A brewery or brewing company is a business that makes and sells beer. The place at which beer is commercially made is either called a brewery or a beerhouse, where distinct sets of brewing equipment are called plant.[1] The commercial brewing of beer has taken place since at least 2500 BC;[2] in ancient Mesopotamia, brewers derived social sanction and divine protection from the goddess Ninkasi.[3][4] Brewing was initially a cottage industry, with production taking place at home; by the ninth century monasteries and farms would produce beer on a larger scale, selling the excess; and by the eleventh and twelfth centuries larger, dedicated breweries with eight to ten workers were being built.[5]

The diversity of size in breweries is matched by the diversity of processes, degrees of automation, and kinds of beer produced in breweries. A brewery is typically divided into distinct sections, with each section reserved for one part of the brewing process.

History

Beer may have been known in Neolithic Europe [6] and was mainly brewed on a domestic scale.[7] In some form, it can be traced back almost 5000 years to Mesopotamian writings describing daily rations of beer and bread to workers. Before the rise of production breweries, the production of beer took place at home and was the domain of women, as baking and brewing were seen as "women's work".

Industrialization

Breweries, as production facilities reserved for making beer, did not emerge until monasteries and other Christian institutions started producing beer not only for their own consumption but also to use as payment. This industrialization of brewing shifted the responsibility of making beer to men.

The oldest, still functional, brewery in the world is believed to be the German state-owned Weihenstephan brewery in the city of Freising, Bavaria. It can trace its history back to 1040 AD.[8] The nearby Weltenburg Abbey brewery, can trace back its beer-brewing tradition to at least 1050 AD.[9]:30 The Žatec brewery in the Czech Republic claims it can prove that it paid a beer tax in 1004 AD.

Early breweries were almost always built on multiple stories, with equipment on higher floors used earlier in the production process, so that gravity could assist with the transfer of product from one stage to the next. This layout often is preserved in breweries today, but mechanical pumps allow more flexibility in brewery design. Early breweries typically used large copper vats in the brewhouse, and fermentation and packaging took place in lined wooden containers. Such breweries were common until the Industrial Revolution, when better materials became available, and scientific advances led to a better understanding of the brewing process. Today, almost all brewery equipment is made of stainless steel. During the Industrial Revolution, the production of beer moved from artisanal manufacture to industrial manufacture, and domestic manufacture ceased to be significant by the end of the 19th century.[10]

Major technological advances

A handful of major breakthroughs have led to the modern brewery and its ability to produce the same beer consistently. The steam engine, vastly improved in 1775 by James Watt, brought automatic stirring mechanisms and pumps into the brewery. It gave brewers the ability to mix liquids more reliably while heating, particularly the mash, to prevent scorching, and a quick way to transfer liquid from one container to another. Almost all breweries now use electric-powered stirring mechanisms and pumps. The steam engine also allowed the brewer to make greater quantities of beer, as human power was no longer a limiting factor in moving and stirring.

Carl von Linde, along with others, is credited with developing the refrigeration machine in 1871. Refrigeration allowed beer to be produced year-round, and always at the same temperature. Yeast is very sensitive to temperature, and, if a beer were produced during summer, the yeast would impart unpleasant flavours onto the beer. Most brewers would produce enough beer during winter to last through the summer, and store it in underground cellars, or even caves, to protect it from summer's heat.

The discovery of microbes by Louis Pasteur was instrumental in the control of fermentation. The idea that yeast was a microorganism that worked on wort to produce beer led to the isolation of a single yeast cell by Emil Christian Hansen. Pure yeast cultures allow brewers to pick out yeasts for their fermentation characteristics, including flavor profiles and fermentation ability. Some breweries in Belgium, however, still rely on "spontaneous" fermentation for their beers (see lambic). The development of hydrometers and thermometers changed brewing by allowing the brewer more control of the process, and greater knowledge of the results.

The modern brewery

Breweries today are made predominantly of stainless steel, although vessels often have a decorative copper cladding for a nostalgic look. Stainless steel has many favourable characteristics that make it a well-suited material for brewing equipment. It imparts no flavour in beer, it reacts with very few chemicals, which means almost any cleaning solution can be used on it (concentrated chlorine [bleach] being a notable exception) and it is very sturdy. Sturdiness is important, as most tanks in the brewery have positive pressure applied to them as a matter of course, and it is not unusual that a vacuum will be formed incidentally during cleaning.

Heating in the brewhouse usually is achieved through pressurized steam, although direct-fire systems are not unusual in small breweries. Likewise, cooling in other areas of the brewery is typically done by cooling jackets on tanks, which allow the brewer to control precisely the temperature on each tank individually, although whole-room cooling is also common.

Today, modern brewing plants perform myriad analyses on their beers for quality control purposes. Shipments of ingredients are analyzed to correct for variations. Samples are pulled at almost every step and tested for [oxygen] content, unwanted microbial infections, and other beer-aging compounds. A representative sample of the finished product often is stored for months for comparison, when complaints are received.

Brewing process

Brewing is typically divided into 9 steps: milling, malting, mashing, lautering, boiling, fermenting, conditioning, filtering, and filling.

Mashing is the process of mixing milled, usually malted, grain with water, and heating it with rests at certain temperatures to allow enzymes in the malt to break down the starches in the grain into sugars, especially maltose. Lautering is the separation of the extracts won during mashing from the spent grain to create wort. It is achieved in either a lauter tun, a wide vessel with a false bottom, or a mash filter, a plate-and-frame filter designed for this kind of separation. Lautering has two stages: first wort run-off, during which the extract is separated in an undiluted state from the spent grains, and sparging, in which extract that remains with the grains is rinsed off with hot water.

Boiling the wort ensures its sterility, helping to prevent contamination with undesirable microbes. During the boil, hops are added, which contribute aroma and flavour compounds to the beer, especially their characteristic bitterness. Along with the heat of the boil, they cause proteins in the wort to coagulate and the pH of the wort to fall, and they inhibit the later growth of certain bacteria. Finally, the vapours produced during the boil volatilize off-flavours, including dimethyl sulfide precursors. The boil must be conducted so that it is even and intense. The boil lasts between 60 and 120 minutes, depending on its intensity, the hop addition schedule, and volume of wort the brewer expects to evaporate.

- Fermenting

Fermentation begins as soon as yeast is added to the cooled wort. This is also the point at which the product is first called beer. It is during this stage that fermentable sugars won from the malt (maltose, maltotriose, glucose, fructose and sucrose) are metabolized into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Fermentation tanks come in many shapes and sizes, from enormous cylindroconical vessels that can look like storage silos, to five-gallon glass carboys used by homebrewers. Most breweries today use cylindroconical vessels (CCVs), which have a conical bottom and a cylindrical top. The cone's aperture is typically around 70°, an angle that will allow the yeast to flow smoothly out through the cone's apex at the end of fermentation, but is not so steep as to take up too much vertical space. CCVs can handle both fermenting and conditioning in the same tank. At the end of fermentation, the yeast and other solids have fallen to the cone's apex can be simply flushed out through a port at the apex. Open fermentation vessels are also used, often for show in brewpubs, and in Europe in wheat beer fermentation. These vessels have no tops, making it easy to harvest top-fermenting yeasts. The open tops of the vessels increase the risk of contamination, but proper cleaning procedures help to control the risk.

Fermentation tanks are typically made of stainless steel. Simple cylindrical tanks with beveled ends are arranged vertically, and conditioning tanks are usually laid out horizontally. A very few breweries still use wooden vats for fermentation but wood is difficult to keep clean and infection-free and must be repitched often, perhaps yearly. After high kräusen, the point at which fermentation is most active and copious foam is produced, a valve known in German as the spundapparat may be put on the tanks to allow the carbon dioxide produced by the yeast to naturally carbonate the beer. This bung device can regulate the pressure to produce different types of beer; greater pressure produces a more carbonated beer.

- Conditioning

When the sugars in the fermenting beer have been almost completely digested, the fermentation process slows and the yeast cells begin to die and settle at the bottom of the tank. At this stage, especially if the beer is cooled to around freezing, most of the remaining live yeast cells will quickly become dormant and settle, along with the heavier protein chains, due simply to gravity and molecular dehydration. Conditioning can occur in fermentation tanks with cooling jackets. If the whole fermentation cellar is cooled, conditioning must be done in separate tanks in a separate cellar. Some beers are conditioned only lightly, or not at all. An active yeast culture from an ongoing batch may be added to the next boil after a slight chilling in order to produce fresh and highly palatable beer in mass quantity.

- Filtering

Filtering the beer stabilizes flavour and gives it a polished, shiny look. It is an optional process. Many craft brewers simply remove the coagulated and settled solids and forgo active filtration. In localities where a tax assessment is collected by government pursuant to local laws, any additional filtration may be done using an active filtering system, the filtered product finally passing into a calibrated vessel for measurement just after any cold conditioning and prior to final packaging where the beer is put into the containers for shipment or sale. The container may be a bottle, can, of keg, cask or bulk tank.

Filters come in many types. Many use pre-made filtration media such as sheets or candles. Kieselguhr, a fine powder of diatomaceous earth, can be introduced into the beer and circulated through screens to form a filtration bed. Filtration ratings are divided into rough, fine, and sterile. Rough filters remove yeasts and other solids, leaving some cloudiness, while finer filters can remove body and color. Sterile filters remove almost all microorganisms.

Brewing companies

Brewing companies range widely in the volume and variety of beer produced, ranging from small breweries, such as Ringwood Brewery, to massive multinational conglomerates, like SABMiller in London or Anheuser-Busch InBev, that produce hundreds of millions of barrels annually. There are organizations that assist the development of brewing, such as the Siebel Institute of Technology in the USA and the Institute of Brewing and Distilling in the UK. In 2012 the four largest brewing companies (Anheuser-Busch InBev, SABMiller, Heineken International, and Carlsberg Group) controlled 50% of the market[11] The biggest brewery in the world is the Belgian-Brazilian company Anheuser-Busch InBev.

Some commonly used descriptions of breweries are:

- Microbrewery – A late-20th-century name for a small brewery. The term started to be supplanted with craft brewer at the start of the 21st century.

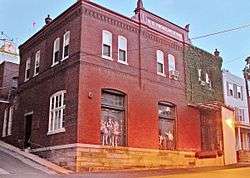

- Brewpub – A brewery whose beer is brewed primarily on the same site from which it is sold to the public, such as a pub or restaurant. If the amount of beer that a brewpub distributes off-site exceeds 75%, it may also be described as a craft or microbrewery.

- Farm brewery – A farm brewery, or farmhouse brewery, is a brewery that primarily brews its beer on a farm. Crops and other ingredients grown on the farm, such as barley, wheat, rye, hops, herbs, spices, and fruits are used in the beers brewed. A farmhouse brewery is similar in concept to a vineyard growing grapes to make wine at the vineyard.[12]

- Regional brewery – An established term for a brewery that supplies beer in a fixed geographical location.

- Macrobrewery or Megabrewery – Terms for a brewery, too large or economically diversified to be a microbrewery, which sometimes carry a negative connotation.

Contract brewing

Contract brewing –When one brewery hires another brewery to produce its beer. The contracting brewer generally handles all of the beer's marketing, sales, and distribution, while leaving the brewing and packaging to the producer-brewery (which confusingly may also be referred to as a contract brewer). Often the contract brewing is performed when a small brewery can not supply enough beer to meet demands and contracts with a larger brewery to help alleviate their supply issues. Some breweries do not own a brewing facility, these contract brewers have been criticized by traditional brewing companies for avoiding the costs associated with a physical brewery.[13]

Gypsy brewing

Gypsy, or nomad, brewing usually falls under the category of contract brewing. Gypsy breweries generally do not have their own equipment or premises. They operate on a temporary or itinerant basis out of the facilities of another brewery, generally making "one-off" special occasion beers.[14] The trend of gypsy brewing spread early in Scandinavia.[15] Their beers and collaborations later spread to America and Australia.[16] Gypsy brewers typically use facilities of larger makers with excess capacity.[16][16]

Prominent examples include Pretty Things, Stillwater Artisanal Ales, Gunbarrel Brewing Company, Mikkeller, and Evil Twin.[17][18] For example, one of Mikkeller's founders, Mikkel Borg Bjergsø, has traveled around the world between 2006 and 2010, brewing more than 200 different beers at other breweries.[19]

Head brewer/brewmaster

The head brewer (UK) or brewmaster (USA) is in charge of the production of beer. The major breweries employ engineers with a chemistry/Biotechnology background.

Brewmasters may have had a formal education in the subject from institutions such as the Siebel Institute of Technology, VLB Berlin, Heriot-Watt University, American Brewers Guild,[20] University of California at Davis, University of Wisconsin,[20] Olds College[21] or Niagara College.[22] They may hold membership in professional organisations such as the Brewers Association, Master Brewers Association, American Society of Brewing Chemists, the Institute of Brewing and Distilling,[23] and the Society of Independent Brewers. Depending on a brewery's size, a brewer may need anywhere from five to fifteen years of professional experience before becoming a brewmaster;[20]

See also

- Beer and breweries by region

- Breweriana—the hobby of brewery advertising collecting

- List of breweries in the United States

- List of microbreweries

- Tower brewery

References

- ↑ Jens Gammelgaard (2013). The Global Brewery Industry. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 52.

- 1 2 "World's oldest beer receipt? – Free Online Library". thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ↑ Susan Pollock, Ancient Mesopotamia,1999:102-103.

- ↑ Hartman, L. F. and Oppenheim, A. L., (1950) "On Beer and Brewing Techniques in Ancient Mesopotamia," Supplement to the Journal of the American Oriental Society, 10. Retrieved 2013-09-20.

- ↑ Thomas F. Glick; et al. (27 Jan 2014). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine. Routledge. p. 102.

- ↑ Prehistoric brewing: the true story, 22 October 2001, Archaeo News. Retrieved 13 September 2008

- ↑ Dreher Breweries, Beer-history

- ↑ "Indulge in the Bavarian Weiss", BeerHunter.com, Michael Jackson, September 2, 1998.

- ↑ Altmann, Lothar (2012). Benediktinerabtei Weltenburg an der Donau (German). Schnell & Steiner-Verlag, Regensburg. ISBN 978-3-7954-4248-4.

- ↑ Cornell, Martyn (2003). Beer: The Story of the Pint. Headline. ISBN 0-7553-1165-5.

- ↑ "Modelo may not quench thirst for beer deals | Reuters". In.reuters.com. 2012-06-29. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ↑ "Class 8M Farm Brewery License".

- ↑ Acitelli, Tom (2013). The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. p. 240. ISBN 9781613743881. OCLC 828193572.

- ↑ Noel, Josh (March 14, 2012). "A Long Road to Realizing Their Pipe Dream". Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ Smith, James (May 15, 2012). "Refreshing Taste of Diplomacy". The Age.

- 1 2 3 O'Neill, Claire (August 14, 2010). "'Gypsy Brewer' Spreads Craft Beer Gospel". National Public Radio.

- ↑ Risen, Clay (October 20, 2010). "The Innovative 'Gypsy Brewers' Shaking Up the Beer World". The Atlantic.

- ↑ Nichols, Lee (March 16, 2013). "Handicapping Local Craft Brews". Austin Chronicle.

- ↑ Miller, Norman (March 28, 2012). "The Beer Nut: Mikkeller Brews Beer on the Run".

- 1 2 3 "How to Become a Brewmaster - Professional Brewer". tree.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-14. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ↑ "Brewmaster & Brewery Operations Management". Oldscollege.ca. 1999-02-22. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ↑ "Canada". Brewers' Guardian. 25 July 2011. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ↑ "Brewmaster". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Breweries. |

- ISBN 3-921690-49-8: Technology Brewing and Malting, Wolfgang Kunze, 2004, 3rd revised edition, VLB Berlin. Available at their website

- BrewersAssociation.org Craft brewer definition from the Brewers association.

- Straub Brewery By John Schlimm, Arcadia Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0-7385-3843-4