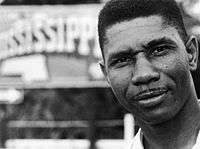

Medgar Evers

| Medgar Evers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Medgar Wiley Evers July 2, 1925 Decatur, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died |

June 12, 1963 (aged 37) Jackson, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Alcorn State University |

| Occupation | Civil rights activist |

| Spouse(s) |

Myrlie Evers (m. 1951–63) (his death) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent(s) |

James Evers (father) Jesse Wright (mother)[1] |

Medgar Wiley Evers (July 2, 1925 – June 12, 1963) was an American civil rights activist from Mississippi who worked to overturn segregation at the University of Mississippi and to enact social justice and voting rights. He was murdered by a white supremacist and Klansman.

A World War II veteran and college graduate, he became active in the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s. He became a field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Following the 1954 ruling of the United States Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education that segregated public schools were unconstitutional, Evers worked to gain admission for African Americans to the state-supported public University of Mississippi. He also worked on voting rights and registration, economic opportunity, access to public facilities, and other changes in the segregated society.

Evers was murdered by Byron De La Beckwith, a member of the White Citizens' Council, a group formed in 1954 to resist integration of schools and civil rights activity. As a veteran, Evers was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.[2][3] His murder and the resulting trials inspired civil rights protests, as well as numerous works of art, music and film. All-white juries failed to reach verdicts in the first two trials of Beckwith. He was convicted in a new state trial in 1994, based on new evidence.

Myrlie Evers, widow of the activist, became a noted activist in her own right, serving as national chair of the NAACP. His brother Charles Evers was the first African-American mayor elected in Mississippi in the post-Reconstruction era when he won in 1969 in Fayette.

Early life

Evers was born July 2, 1925, in Decatur, Mississippi, the third of the five children (including older brother Charles Evers) of Jesse (Wright) and James Evers. The family included Jesse's two children from a previous marriage.[4][5] The Evers family owned a small farm, and James also worked at a sawmill.[6] Evers walked twelve miles to attend segregated schools, and earned his high school diploma.[7]

Evers served in the United States Army during World War II from 1943 to 1945. He was sent to the European Theater and he fought in the Battle of Normandy in June 1944. After the end of the war, Evers was honorably discharged as a sergeant.[8]

In 1948, Evers enrolled at Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College[9] (a historically black college, now Alcorn State University) majoring in business administration.[10] He also competed on the debate, football, and track teams, sang in the choir, and was junior class president.[11] He earned his Bachelor of Arts in 1952.[10]

On December 24, 1951, he married classmate Myrlie Beasley.[12] Together they had three children: Darrell Kenyatta, Reena Denise, and James Van Dyke Evers.[13]

Activism

The couple moved to Mound Bayou, Mississippi a town developed by African Americans, where Evers became a salesman for T. R. M. Howard's Magnolia Mutual Life Insurance Company.[14] Howard was also president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL);[15] Evers helped organize the RCNL's boycott of gasoline stations that denied blacks the use of the stations' restrooms.[16] Evers and his brother Charles also attended the RCNL's annual conferences in Mound Bayou between 1952 and 1954, which drew crowds of ten thousand or more.[17]

In 1954, Evers applied to the segregated University of Mississippi Law School, but his application was rejected because of his race.[18] He submitted his application in concert with the NAACP as a test case.[19] That year the US Supreme Court had ruled that segregation of public schools (which included state universities) was unconstitutional.

On November 24, 1954[20], Evers was named the NAACP's first field secretary for Mississippi.[6] In this position, he helped organize boycotts and set up new local chapters of the NAACP. He was involved with James Meredith's efforts to enroll in the University of Mississippi in the early 1960s.[19] Evers also helped Dr. Gilbert Mason, Sr., organize the Biloxi wade-ins, protests against segregation of public beaches on the Mississippi Gulf Coast.[21] In addition, Evers also helped integrate Jackson's privately owned buses and was trying to integrate the public parks, led voter registration drives, and used boycotts to integrate Leake County schools and the Mississippi State Fair.[22]

Evers's civil rights leadership and investigative work made him a target of white supremacists. The White Citizens' Council was founded in Mississippi, with numerous local chapters, to resist integration of schools and civil rights goals. In the weeks before Evers' death, the leader encountered new levels of hostility. His public investigations into the 1955 lynching of teenaged Emmett Till and his vocal support of Clyde Kennard had made him a prominent black leader. On May 28, 1963, a Molotov cocktail was thrown into the carport of his home.[23] On June 7, 1963, Evers was nearly run down by a car after he emerged from the NAACP office in Jackson.[14]

Assassination

Medgar Evers lived with the constant threat of death upon him, with a heavy Ku Klux Klan and white supremacist population in the area in which he both lived and advocated. The risk had grown so great in the time before his death that Evers and his wife Myrlie had trained their children on exactly what to do if there was a shooting, bombing, or other kind of attack on their lives[24]. Evers, who was regularly followed home by at least two FBI cars and one police car, arrived at his home on the morning of his death without an escort, with none of his usual protection for reasons unspecified by the FBI or local police. Many believe that many members of the police force at the time were members of the Klan.[25]

In the early morning of June 12, 1963, just hours after President John F. Kennedy's nationally televised Civil Rights Address, Evers pulled into his driveway after returning from a meeting with NAACP lawyers. Evers's family had worried for his safety the day of his assassination, and Evers himself had warned his wife that he felt himself in a greater danger than usual. When he arrived home, Evers's family was waiting for him, and his children exclaimed to his wife, Myrlie, that he had arrived[24]. Emerging from his car and carrying NAACP T-shirts that read "Jim Crow Must Go", Evers was struck in the back with a bullet fired from an Enfield 1917 rifle; the bullet ripped through his heart. Initially thrown to the ground by the impact of the shot, Evers rose and staggered 30 feet (10 meters) before collapsing. His wife Myrlie was the first to find him outside of their front door.[24] He was taken to the local hospital in Jackson, Mississippi where he was initially refused entry because of his race. His family explained who he was and he was admitted; he died in the hospital 50 minutes later.[26] Evers was the first African American to be admitted to an all white hospital in Mississippi, an ironic final achievement for the dying activist[24]. Mourned nationally, Evers was buried on June 19 in Arlington National Cemetery, where he received full military honors before a crowd of more than 3,000.[15][27]

After Evers was assassinated, an estimated 5,000 people marched from the Masonic Temple on Lynch Street to the Collins Funeral Home on North Farish Street in Jackson, Mississippi. Allen Johnson, Reverend Martin Luther King and other civil rights leaders led the procession.[28] The Mississippi police came prepared with riot gear and rifles in case the protests turned violent. While tensions were initially high in the stand off between police and marchers, and in many similar situations around the state, leaders of the movement were able to maintain a nonviolent atmosphere among their followers.[25]

On June 21, 1963, Byron De La Beckwith, a fertilizer salesman and member of the White Citizens' Council (and later of the Ku Klux Klan), was arrested for Evers's murder.[30] District Attorney and future governor Bill Waller prosecuted De La Beckwith.[31] All-white juries twice that year - February and April 1964[32] - deadlocked on De La Beckwith's guilt and failed to reach a verdict. At the time, most blacks were disenfranchised by Mississippi's constitution and voter registration practices; this meant they were also excluded from juries, which were based on registered voters.

Myrlie Evers never gave up the fight for a conviction of her husband's murderer, and waited until a new judge had been assigned in the county before taking action to take her case against De La Beckwith back into the courtroom.[24] In 1994, De La Beckwith was prosecuted by the state based on new evidence. Bobby DeLaughter was the prosecutor. During the trial, the body of Evers was exhumed from his grave for an autopsy.[3] De La Beckwith was convicted of murder on February 5, 1994, after having lived as a free man for much of the three decades following the killing. (He had been imprisoned from 1977 to 1980 on separate charges: conspiring to murder A.I. Botnick.) In 1997,[33]De La Beckwith appealed his conviction in the Evers case, but the Mississippi Supreme Court upheld it. He later died at age 80 in prison in January 2001. [34][35]

Legacy

Evers was memorialized by leading Mississippi and national authors, both black and white: Eudora Welty, James Baldwin, Margaret Walker and Anne Moody.[36] In 1963, he was awarded the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP.[37] In 1969, Medgar Evers College was established in Brooklyn, New York, as part of the City University of New York.

Evers's widow, Myrlie Evers co-wrote the book For Us, the Living with William Peters in 1967. In 1983, a movie was made based on the book. Celebrating Evers's life and career, it starred Howard Rollins Jr. and Irene Cara as Medgar and Myrlie Evers, airing on PBS. The film won the Writers Guild of America award for Best Adapted Drama.[38]

In 1969 a community pool in the Central District neighborhood of Seattle, WA was named after Evers, honoring his life.[39]

On June 28, 1992, the city of Jackson, Mississippi, erected a statue in honor of Evers. All of Delta Drive (part of U.S. Highway 49) in Jackson was renamed in Evers's honor. In December 2004, the Jackson City Council changed the name of the city's airport to "Jackson-Medgar Wiley Evers International Airport" (Jackson-Evers International Airport) in his honor.[40]

His widow Myrlie Evers became a noted activist in her own right, eventually serving as chairperson of the NAACP.[41] Medgar's brother Charles Evers returned to Jackson in July 1963 and served briefly with the NAACP in his slain brother's place. He remained involved in Mississippi civil rights activities for many years, was the first African-American mayor elected in the state in 1969, and resides in Jackson.[42]

On the 40-year anniversary of Evers's assassination, hundreds of civil rights veterans, government officials, and students from across the country gathered around his grave site at Arlington National Cemetery to celebrate his life and legacy. Barry Bradford and three students—Sharmistha Dev, Jajah Wu and Debra Siegel, formerly of Adlai E. Stevenson High School in Lincolnshire, Illinois—planned and hosted the commemoration in his honor.[43] Evers was the subject of the students' research project.[44]

In October 2009, Navy Secretary Ray Mabus, a former Mississippi governor, announced that USNS Medgar Evers (T-AKE-13), a Lewis and Clark-class dry cargo ship, would be named in the activist's honor.[45] The ship was christened by Myrlie Evers-Williams on November 12, 2011.[46]

In June 2013, a statue of Evers was erected at his alma mater, Alcorn State University, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his death.[47] Alumni and guests from around the world gathered to recognize his contributions to American society.

Evers was honored in a tribute at Arlington National Cemetery on the 50th anniversary of his death.[48] Former President Bill Clinton, Attorney General Eric Holder, Navy Secretary Ray Mabus, Senator Roger Wicker and NAACP President Benjamin Jealous all spoke commemorating Evers.[49][50] Evers's widow, Myrlie Evers-Williams, spoke on his contributions to the advancement of civil rights:[51]

- "Medgar was a man who never wanted adoration, who never wanted to be in the limelight. He was a man who saw a job that needed to be done and he answered the call and the fight for freedom, dignity and justice not just for his people but all people."

He was identified as a Freedom hero by The My Hero Project.[7]

In 2017, the Medgar and Myrlie Evers House was named as a National Historic Landmark.[52]

In popular culture

Musician Bob Dylan wrote his 1963 song "Only a Pawn in Their Game" about the assassination.[53] Nina Simone wrote and sang "Mississippi Goddam" about the Evers case, and Phil Ochs wrote the songs "Another Country" and "Too Many Martyrs" (also titled "The Ballad Of Medgar Evers") in response to the killing. Matthew Jones and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Freedom Singers recorded the latter song.[53] Eudora Welty's short story "Where is the Voice Coming From", in which the speaker is the imagined assassin of Medgar Evers, was published in The New Yorker in July 1963.[54]

The film Ghosts of Mississippi (1996) directed by Rob Reiner, tells the story of the 1994 trial of Beckwith, in which prosecutor DeLaughter of the Hinds County District Attorney's office secured a conviction in state court. Beckwith and DeLaughter were played by James Woods and Alec Baldwin, respectively; Whoopi Goldberg played Myrlie Evers. Evers was portrayed by James Pickens Jr. The film was based on a book of the same name.[55][56]

Robert DeLaughter wrote a first-person narrative article entitled "Mississippi Justice" published in Reader's Digest, and a book, Never Too Late: A Prosecutor's Story of Justice in the Medgar Evers Case (2001), based on his experiences.[57]

Wadada Leo Smith's album Ten Freedom Summers contains a track called "Medgar Evers: A Love-Voice of a Thousand Years' Journey for Liberty and Justice".[58]

The 2016 documentary I Am Not Your Negro describes the author James Baldwin's reaction to Evers's assassination.[59]

See also

References

- ↑ per Charles Evers bio "Have no Fear" page 5

- ↑ Ellis, Kate; Smith, Stephen (2011). "State of Siege: Mississippi Whites and the Civil Rights Movement". American Public Media. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- 1 2 Baden, M. M. (2006): Chapter III: Time of Death and Changes after Death. Part 4: Exhumation. In: Spitz, W. U. & Spitz, D. J. (eds): Spitz and Fisher’s Medicolegal Investigation of Death. Guideline for the Application of Pathology to Crime Investigations (Fourth edition), Charles C. Thomas, pp. 174-83; Springfield, Illinois.

- ↑ "James Charles Evers", Black Past

- ↑ "Medgar W. Evers – Civil Rights Activist". mememorial.org.

- 1 2 Williams, Reggie. (2005, July 2). "Remembering Medgar," Afro King - American Red Star, p. A.1. Retrieved October 26, 2009, from Black Newspapers.

- 1 2 Sina, “Freedom Hero: Medgar Wiley Evers.” The My Hero Project, 2005. Retrieved October 25, 2009.

- ↑ Evers-Williams, Myrlie; Marable, Manning (2005). The Autobiography of Medgar Evers: A Hero's Life and Legacy Revealed Through His Writings, Letters, and Speeches. Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 0-465-02177-8.

- ↑ Arroyo, Elizabeth (2006). Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History (2nd ed.). p. 738.

- 1 2 Harvard University W.E.B. Du Bois Institute. "EVERS, MEDGAR (2 JULY 1925 - 12 JUNE 1963), CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIVIST, WAS...". dubois.fas.harvard.edu.

- ↑ Padgett, John B., “Medgar Evers”. The Mississippi Writers Page, University of Mississippi. 2008. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ↑ THOMAS United States Library of Congress (June 9, 2003). "Commending Medgar Wiley Evers and his widow, Myrlie Evers-Williams for their lives and accomplishments, designating a Medgar Evers National Week of Remembrance, and for other purposes (Introduced in Senate - IS)". thomas.loc.gov.

- ↑ Dustin Cardon; Jackson Free Press (January 21, 2013). "Myrlie Evers-Williams". jacksonfreepress.com.

- 1 2 National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (June 24, 2013). "NAACP HISTORY: MEDGAR EVERS". naacp.org. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013.

- 1 2 Wesleyan University (June 24, 2013). "Medgar Evers: July 2, 1925-June 12, 1963" (PDF). wesleyan.edu.

- ↑ Hayden Lee Hinton; AuthorHouse (2010). America Taken Hostage. books.google.com. p. 121. ISBN 978-1438985800.

- ↑ David T. Beito and Linda Royster Beito, Black Maverick: T. R. M. Howard's Fight for Civil Rights and Economic Power (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), pp. 75, 80-81.

- ↑ Myra Ribeiro (1 October 2001). The Assassination of Medgar Evers. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8239-3544-4. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- 1 2 Nikki L. M. Brown; Barry M. Stentiford (September 30, 2008). The Jim Crow Encyclopedia: Greenwood Milestones in African American History. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 277–78. ISBN 978-0-313-34181-6. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ↑ Wynne, Ben (2011). Black America: A State-By-State Historical Encyclopedia. p. 436.

- ↑ Dorian Randall (June 17, 2013). Medgar Evers: Direct Action. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ↑ Arroyo, Elizabeth (2006). Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History (2nd ed.). p. 738.

- ↑ Hank Johnson (January 21, 2013). "H.Res.1022 - Honoring the life and sacrifice of Medgar Evers and congratulating the United States Navy for naming a supply ship after Medgar Evers.". beta.congress.gov.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bates, Karen Grigsby. "Trials & Transformation: Myrlie Evers' 30-Year Fight to Convict Medgar's Accused Killer." Emerge 02 1994: 35. ProQuest. Web. 27 May 2017

- 1 2 Moody, Anne. Coming of Age in Mississippi. New York: Dell Pub., 1976. Print

- ↑ Birnbaum, p. 490.

- ↑ Orejel, Keith. "The Federal Government's Response to Medgar Evers's Funeral." Southern Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 2/3, Winter/Spring2012, pp. 37-54. EBSCOhost, www.pierce.ctc.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=85882790&scope=site.

- ↑ O'Brien, M. J. (March 1, 2013). We Shall Not Be Moved: The Jackson Woolworth's Sit-In and the Movement It Inspired. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 118. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ↑ Medgar Evers home tour Retrieved December 25, 2013

- ↑ Dufresne, Marcel (October 1991). "Exposing the Secrets of Mississippi Racism". American Journalism Review.

- ↑ Jerry Mitchell (The Clarion-Ledger) (June 2, 2013). "Medgar Evers: Assassin's gun forever changed a family". USA Today.

- ↑ "White Supremacist Indicted for Third Time in Shooting Death of Medgar Evers". Jet (vol. 79 no. 12). January 7, 1991.

- ↑ Batten, Donna (2010). Gale Encyclopedia of American Law (3rd ed.). p. 266.

- ↑ "Deliverance." People Weekly Feb 21 1994: 60. ProQuest. Web. 27 May 2017

- ↑ "Unfinished Business." U.S.News & World Report Jan 24 1994: 14. ProQuest. Web. 27 May 2017

- ↑ Minrose Gwin"Mourning Medgar: Justice, Aesthetics, and the Local", Southern Spaces, 2008.

- ↑ "NAACP Spingarn Medal". Naacp.org. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ↑ "For Us the Living: The Medgar Evers Story". www.allrovi.com. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ↑ "Seattle Parks and Recreation History of Medgar Evers pool" (PDF). Seattle Parks and Recreation History. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Jackson-Medgar Wiley Evers International Airport". Jackson Municipal Airport Authority. 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ↑ "NAACP Chairwoman Myrlie Evers-Williams Will Not Seek Re-Election". Jet. 1998-03-02. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Charles Evers's biography, PBS". Pbs.org. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Medgar Evers", Arlingon Cemetery. Note: Bradford later was notable for his work in helping reopen the Mississippi Burning and Clyde Kennard cases.

- ↑ Lottie L. Joiner (July 2003), "The nation remembers Medgar Evers", The Crisis, 110(4), 8. Retrieved October 26, 2009, from Research Library Core.

- ↑ Mabus, Ray, "The Navy Honors a Civil Rights Pioneer." The White House Blog. October 9, 2009. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ↑ "A Memorial for Medgar", San Diego Union-Tribune, November 13, 2011.

- ↑ Therese Apel (June 12, 2013). "Mississippi marks 50th anniversary of Medgar Evers' death". reuters.com.

- ↑ Krissah Thompson (June 5, 2013). "Memorial service for Medgar Evers held at Arlington National Cemetery". washingtonpost.com.

- ↑ Ashley Southall (June 5, 2013). "Paying Tribute to a Seeker of Justice, 50 Years After His Assassination". nytimes.com.

- ↑ Valerie Bonk; Associated Press (June 5, 2013). "HOLDER PRAISES SLAIN BLACK ACTIVIST MEDGAR EVERS". bigstory.ap.org.

- ↑ Associated Press (June 5, 2013). "Medgar Evers honored at Arlington National Cemetery". The Clarion-Ledger.

- ↑ "Interior Department Announces 24 New National Historic Landmarks | U.S. Department of the Interior". Doi.gov. Retrieved 2017-01-14.

- 1 2 "NAACP Evers biography". Naacp.org. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ↑ Eudora Welty, "Where Is The Voice Coming From?", The New Yorker, July 6, 1963.

- ↑ Vollers, Maryanne (April 1995). Ghosts of Mississippi: the murder of Medgar Evers, the trials of Byron de la Beckwith, and the haunting of the new South. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-91485-7. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ↑ "Biography of Bobby B. DeLaughter". 2002. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ↑ Never Too Late: A Prosecutor's Story of Justice in the Medgar Evers Case. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743223393. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Ten Freedom Summers". Cuneiform Records. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ↑ Young, Deborah (September 20, 2016). "‘I Am Not Your Negro’: Film Review | TIFF 2016". The Hollywood Reporter.

Further reading

- Gwin, Minrose (2013). Remembering Medgar Evers: Writing the Long Civil Rights Movement. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820335636.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Medgar Evers. |

- JFK First Draft Condolence Letter to Medgar Evers’ Widow, June 12, 1963 Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Audio recording of T. R. M. Howard's eulogy at the memorial service for Medgar Evers, June 15, 1963, Jackson, Mississippi.

- Myrlie Evers (28 June 1963). 'He said he wouldn't mind dying - if...'. LIFE. pp. 34–47.

- Medgar Evers in the U.S. Federal Census American Civil Rights Pioneers

- Medgar Evers biography at africawithin.com

- Medgar Evers on IMDb

- imbd.com

- FBI article: Civil Rights in the ‘60s: Justice for Medgar Evers

- Medgar Evers's FBI file hosted at the Internet Archive

- Medgar Evers at Find a Grave Retrieved February 22, 2010

- "Medgar Evers," One Person, One Vote