Mdina

| Mdina L-Imdina Città Notabile, Città Vecchia Maleth, Melite, Melita | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City and Local council | |||

|

| |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): The Silent City | |||

| |||

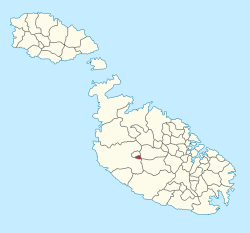

| Coordinates: 35°53′9″N 14°24′11″E / 35.88583°N 14.40306°ECoordinates: 35°53′9″N 14°24′11″E / 35.88583°N 14.40306°E | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Region | Northern Region | ||

| District | Western District | ||

| Established |

c. 8th century BC as Maleth c. 11th century as Mdina | ||

| Borders | Attard, Mtarfa, Rabat | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Peter Dei Conti Sant Manduca (PN) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 0.9 km2 (0.3 sq mi) | ||

| Population (March 2014) | |||

| • Total | 292 | ||

| • Density | 320/km2 (840/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Midjan (m), Midjana (f), Midjani (p) | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal code | MDN | ||

| Dialing code | 356 | ||

| ISO 3166 code | MT-29 | ||

| Patron saints |

St. Peter St. Paul Our Lady of Mount Carmel | ||

| Day of festa |

29 June 4th Sunday of July | ||

| Website | Official website | ||

| Buses 50, 51, 52, 53, 56 from Valletta terminus, stop at bus stop named "Rabat 3"[1] | |||

Mdina (English: Notabile, or Maltese: L-Imdina [lɪmˈdɪnɐ]; Phoenician: 𐤌𐤋𐤉𐤈𐤄, Melitta, Ancient Greek: Melitte, Μελίττη, Arabic: Madinah, لمدينة, Italian: Medina), also known by its titles Città Vecchia or Città Notabile, is a fortified city in the Northern Region of Malta, which served as the island's capital from antiquity to the medieval period. The city is still confined within its walls, and has a population of just under 300, but it is contiguous with the town of Rabat, which takes its name from the Arabic word for suburb, and has a population of over 11,000 (as of March 2014).[2]

The city was founded as Maleth in around the 8th century BC by Phoenician settlers, and was later renamed Melite by the Romans. Ancient Melite was larger than present-day Mdina, and it was reduced to its present size during the Byzantine or Arab occupation of Malta. During the latter period, the city adopted its present name, which derives from the Arabic word medina. The city remained the capital of Malta throughout the Middle Ages, until the arrival of the Order of St. John in 1530, when Birgu became the administrative centre of the island. Mdina experienced a period of decline over the following centuries, although it saw a revival in the early 18th century. At this point, it acquired several Baroque features, although it did not lose its medieval character.

Mdina remained the centre of the Maltese nobility and religious authorities, but it never regained its pre-1530 importance, giving rise to the popular nickname the "Silent City" by both locals and visitors.[3] Mdina is on the tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and it is now one of the main tourist attractions in Malta.[4]

History

Antiquity

The plateau on which Mdina is built has been inhabited since prehistory, and by the Bronze Age it was a place of refuge since it was naturally defensible.[5] The Phoenicians colonized Malta in around the 8th century BC, and they founded the city of Maleth on this plateau.[6] It was taken over by the Roman Republic in 218 BC, becoming known as Melite. The Punic-Roman city was about three times the size of present-day Mdina, extending into a large part of modern Rabat.[7]

According to the Acts of the Apostles, when Paul the Apostle was shipwrecked on Malta in 60 AD, he was greeted by Publius, the governor of Melite, and he cured his sick father.[Acts 28:1-10] According to tradition, the population of Melite converted to Christianity, and Publius became the first Bishop of Malta and then Bishop of Athens before being martyred in 112 AD.[8][9]

Very few remains of the Punic-Roman city survive today. The most significant are the ruins of the Domvs Romana, in which several well-preserved mosaics, statues and other remains were discovered. Remains of the podium of a Temple of Apollo, fragments of the city walls and some other sites have also been excavated.[10]

Medieval period

At some point following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, a retrenchment was built within the city, reducing it to its present size. This was done to make the city's perimeter more easily defensible, and similar reductions in city sizes were common around the Mediterranean region in the early Middle Ages. Although it was traditionally assumed that the retrenchment was built by the Arabs, it has been suggested that it was actually built by the Byzantine Empire in around the 8th century, when the threat from the Arabs increased.[5]

In 870, Byzantine Melite, which was ruled by governor Amros (probably Ambrosios), was besieged by Aghlabids led by Halaf al-Hādim. He was killed in the fighting, and Sawāda Ibn Muḥammad was sent from Sicily to continue the siege following his death. The duration of the siege is unknown, but it probably lasted for some weeks or months. After Melite fell to the invaders, the inhabitants were massacred, the city was destroyed and its churches were looted. Marble from Melite's churches was used to build the castle of Sousse.[11]

According to Al-Himyarī, Malta remained almost uninhabited until it was resettled in 1048 or 1049 by a Muslim community and their slaves, who built a settlement called Medina on the site of Melite. Archaeological evidence suggests that the city was already a thriving Muslim settlement by the beginning of the 11th century, so 1048–49 might be the date when the city was officially founded and its walls were constructed.[12] The layout of the new city was completely different to that of ancient Melite.[10] Mdina still has features typical of a medina, a legacy of the period of Arab rule.

The Byzantines besieged Medina in 1053–54, but were repelled by its defenders.[13] The city surrendered peacefully to Roger I of Sicily after a short siege in 1091,[14] and Malta was subsequently incorporated into the County and later the Kingdom of Sicily, being dominated by a succession of feudal lords. A castle known as the Castellu di la Chitati was built on the southeast corner of the city near the main entrance, probably on the site of an earlier Byzantine fort.

The population of Malta during the fifteenth century was about 10,000, with town life limited to Mdina, Birgu and the Gozo Citadel. Mdina was comparatively small and partly uninhabited and by 1419, it was already outgrown by its suburb, Rabat.[15] Under Aragonese rule, local government rested on the Università, a communal body based in Mdina, which collected taxation and administered the islands' limited resources. At various points during the fifteenth century, this town council complained to its Aragonese overlords that the islands were at the mercy of the sea and the saracens.[16]

The city withstood a siege by Hafsid invaders in 1429.[17] While the exact number of casualties or Maltese who were carried into slavery is unknown, the islands suffered depopulation in this raid.

Hospitaller rule

When the Order of Saint John took over in Malta in 1530, the nobles ceremoniously handed over the keys of the city to Grand Master Philippe Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, but the Order settled in Birgu and Mdina lost its status as capital city.[18] In the 1540s, the fortifications began to be upgraded during the magistracy of Juan de Homedes y Coscon,[19] and in 1551 the city withstood a brief Ottoman attack.[20]

During the Great Siege of Malta in 1565, Mdina was the base of the Order's cavalry, which made occasional sorties on the invading Ottomans. On 7 August 1565, the cavalry attacked the unprotected Ottoman field hospital, which led in the invaders abandoning a major assault on the main fortifications in Birgu and Senglea. The Ottomans attempted to take Mdina in September so as to winter there, but abandoned their plans when the city fired its cannon, leading them to believe that it had ammunition to spare. After the siege, Maltese military engineer Girolamo Cassar drew up plans to reduce Mdina's size by half and turning it into a fortress, but these were never implemented due to protests by the city's nobles.[20] The fortifications were again upgraded in the mid-17th century, when the large De Redin Bastion was built at the centre of the land front.[21]

Mdina suffered severe damage during the 1693 Sicily earthquake, although no casualties were reported. The 13th-century Cathedral of St. Paul was partially destroyed, and it was rebuilt by Lorenzo Gafà in the Baroque style between 1697 and 1703.[22]

On 3 November 1722, newly elected Grand Master António Manoel de Vilhena issued orders for the restoration and renovation of Mdina.[23] This renovation was entrusted to the French architect and military engineer Charles François de Mondion, who introduced strong French Baroque elements into what was still a largely medieval city. At this point, large parts of the fortifications and the city entrance were completely rebuilt. The remains of the Castellu di la Chitati were demolished to make way for Palazzo Vilhena, while the main gate was walled up and a new Mdina Gate was built nearby. Several public buildings were also built, including the Banca Giuratale and the Corte Capitanale. The last major addition to the Mdina fortifications was Despuig Bastion, which was completed in 1746.[24]

French occupation and British rule

On 10 June 1798, Mdina was captured by French forces without much resistance during the French invasion of Malta.[25] A French garrison remained in the city, but a Maltese uprising broke out on 2 September of that year. The following day, rebels entered the city through a sally port and massacred the garrison of 65 men.[26] These events marked the beginning of a two-year uprising and blockade, and the Maltese set up a National Assembly which met at Mdina's Banca Giuratale.[27] The rebels were successful, and in 1800 the French surrendered and Malta became a British protectorate.[20]

From 1883 to 1931, Mdina was linked with Valletta by the Malta Railway.[28]

Present day

Today, Mdina is one of Malta's major tourist attractions, hosting about 750,000 tourists a year.[29] No cars (other than a limited number of residents, emergency vehicles, wedding cars and hearses) are allowed in Mdina, partly why it has earned the nickname 'the Silent City'. The city displays an unusual mix of Norman and Baroque architecture, including several palaces, most of which serve as private homes.

An extensive restoration of the city walls was undertaken between 2008 and 2016.[30]

Places of interest

The following are a number of historic and monumental buildings around Mdina:[31]

- The city walls, including Mdina Gate, Greeks Gate and the Torre dello Standardo

- St. Paul's Cathedral

- Palazzo Vilhena (National Museum of Natural History)

- Palazzo Falson (Norman House)

- Palazzo Gatto Murina

- Palazzo Santa Sofia

- Palazzo Costanzo

- Banca Giuratale

- Corte Capitanale (city hall)

- St. Agatha's Chapel

- St. Nicholas' Chapel

- St Roque's Church

- Mdina Dungeons

- Carmelite Church & Convent

- Mdina Experience

- St Peter's Church and Monastery

- Bastion Square

- Domvs Romana, ruins of a Roman townhouse just outside the city

Sports

Founded in 2006, the Mdina Knights are currently enjoying a positive moment in the third division league organised by Malta's football governing body, the Malta Football Association. The national sports stadium, the Ta' Qali National Stadium, is located close to the town.

Streets in Mdina

- Misraħ il-Kunsill (Council Square)

- Pjazza San Pawl (St Paul Square)

- Pjazza San Publiju (St Publius Square)

- Pjazza tal-Arċisqof (Archbishop Square)

- Pjazza tas-Sur (Bastion Square)

- Pjazzetta Beata Marija Adeodata Pisani (Blessed Maria Adeodata Pisani Square)

- Triq Inguanez (Inguanez Street)

- Triq is-Sur (Bastion Street)

- Triq San Pawl (St Paul Street)

- Triq Santu Rokku (St Roch Street)

- Triq Villegaignon (Villegaignon Street)

In popular culture

- Mdina (together with Birgu and Gozo) plays a significant role in The Disorderly Knights, the third book of the acclaimed Lymond Chronicles by Dorothy Dunnett, which is set around the events of the Dragut Raid of 1551 when the Ottomans briefly besieged the city.

- In White Wolf Publishing's World of Darkness, Mdina is the European capital of clan Lasombra.

- In the 2007 novel Snakehead by Anthony Horowitz, Mdina is the site of an "ambush" where MI6 intends to retrieve Alex Rider's father John.

- In the first season of HBO's Game of Thrones, Mdina was the filming location for the series' fictional capital city of King's Landing.[32]

Gallery

.jpg)

Mdina Gate, the city's main entrance,designed by the French architect Charles François de Mondion in 1724.

Mdina Gate, the city's main entrance,designed by the French architect Charles François de Mondion in 1724. Cathedral's interior

Cathedral's interior

Typical narrow medieval street

Typical narrow medieval street Elaborate Maltese door in Mdina

Elaborate Maltese door in Mdina Traditional medieval Maltese balcony

Traditional medieval Maltese balcony Palazzo de Piro

Palazzo de Piro Garden archway

Garden archway Part of the fortifications of Mdina

Part of the fortifications of Mdina Palazzo Feriol

Palazzo Feriol The Maltacom Building

The Maltacom Building

Palazzo del Prelato

Palazzo del Prelato Casa Mdina

Casa Mdina

References

- ↑ "Route Map". Malta Public Transport. 19 April 2016. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016.

- ↑ "Estimated Population by Locality 31st March, 2014". Government of Malta. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015.

- ↑ Craven, John (2 March 2009). "Celebrity travel: Starry knights and three-pin plugs in Malta". Daily Mail. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ↑ Blasi, Abigail (29 September 2014). "Top 10 day trips in Malta". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015.

- 1 2 Spiteri & 2004–2007, pp. 3–4

- ↑ Cassar 2000, pp. 53–54

- ↑ Sagona 2015, p. 273

- ↑ "Latin Saints of the Orthodox Patriarchate of Rome". Orthodox England. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016.

- ↑ "Orthodox Malta". Orthodox England. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016.

- 1 2 Testa, Michael (19 March 2002). "New find at Mdina most important so far in old capital". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016.

- ↑ Brincat 1995, p. 11

- ↑ Blouet 2007, p. 41

- ↑ Brincat 1995, p. 12

- ↑ Dalli, Charles (2005). "The Siculo-African Peace and Roger I's Annexation of Malta in 1091". In Cortis, Toni; Gambin, Timothy. De Triremibus: Festschrift in honour of Joseph Muscat (PDF). Publishers Enterprises Group (PEG) Ltd. p. 273. ISBN 9789990904093. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2014.

- ↑ Luttrell, Anthony (1975). Medieval Malta: studies on Malta before the Knights. Rome: The British School at Rome. p. 55.

- ↑ Vann, Theresa M. (2004). "The Militia of Malta". The Journal of Medieval Military History. 2: 137–142.

- ↑ Cauchi, Mark (12 September 2004). "575th anniversary of the 1429 Siege of Malta". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ↑ Borg 2002, p. 124

- ↑ Spiteri & 2004–2007, p. 9

- 1 2 3 Grima, Noel (15 June 2015). "The Mdina siege of 1429 was 'greater than the Great Siege' of 1565". The Malta Independent. Archived from the original on 15 August 2015.

- ↑ "De Redin Bastion – Mdina" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ↑ Montanaro Gauci, Gerald (11 January 2015). "Mdina cathedral destroyed in the 1693 earthquake". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 13 December 2015.

- ↑ De Lucca, Denis (1979). "Mdina: Baroque town planning in 18th century Mdina". Heritage: An encyclopedia of Maltese culture and civilization. Midsea Books Ltd. 1: 21–25.

- ↑ "Despuig Bastion – Mdina" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2015.

- ↑ Castillo 2006, p. 103

- ↑ Goodwin 2002, p. 48

- ↑ "Malta under the French: The Blockade". kagoon.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015.

- ↑ "The Route". maltarailway.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016.

- ↑ Zammit, Ninu (12 December 2006). "Restoration of forts and fortifications". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ↑ "Mdina bastions restoration works completed". Malta Today. 5 April 2016. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016.

- ↑ Thake, Conrad Gerald (2017). "Architecture and urban transformations in Mdina during the reign of Grand Master Anton Manoel de Vilhena (1722-1736)". ArcHistoR (AHR - Architecture History Restoration). Università Mediterranea di Reggio Calabria. 4 (7): 88. ISSN 2384-8898. doi:10.14633/AHR054. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017.

- ↑ Newton, Jennifer (30 April 2014). "The real-life locations for Game Of Thrones: Stunning locations where TV’s smash hit swords and sorcery show is filmed". Daily Mail. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mdina. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mdina. |

Bibliography

- Blouet, Brian W. (2007). The Story of Malta. Allied Publications. ISBN 9789990930818.

- Borg, Victor Paul (2002). The Rough Guide to Malta & Gozo. Rough Guides. ISBN 9781858286808.

- Brincat, Joseph M. (1995). "Malta 870–1054 Al-Himyari's Account and its Linguistic Implications" (PDF). Valletta: Said International. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2015.

- Castillo, Dennis Angelo (2006). The Maltese Cross: A Strategic History of Malta. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313323294.

- Goodwin, Stefan (2002). Malta, Mediterranean Bridge. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780897898201.

- Sagona, Claudia (2015). The Archaeology of Malta. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107006690.

- Spiteri, Stephen C. (2004–2007). "The 'Castellu di la Chitati' the medieval castle of the walled town of Mdina" (PDF). Arx – Online Journal of Military Architecture and Fortification (1–4). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2015.